There’s some irony in celebrating the two hundredth anniversary of the British defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, given Prime Minister David Cameron’s promise to hold a referendum within two years to decide if Britain should leave the European Union. We’ve been warned not to crow over the victory and upset the French, but flaunting it as a solely British triumph also risks snubbing the Germans and other Continental allies: as well as Blucher’s Prussian forces, over half of Wellington’s army was made up of German and Dutch and other nationalities.

Nevertheless, Britain has got Waterloo fever. With the anniversary coming on June 18, documentaries are presenting Wellington, the Iron Duke, as more malleable than first appears, and lauding Napoleon as a hero, rather than as the megalomaniac “Boney.” In Broadstairs in Kent, a horse-drawn post-chaise charging through the streets will recreate Major Percy’s landing and his ride to bring the news of victory to London. In Perth in Scotland a march by the Scots Greys will look back to their famous cavalry charge, celebrated by Lady Elizabeth Butler in her painting Scotland for Ever!

And of course, there are the exhibitions. If you like prints and satires, the richest hoard is on display at the British Museum Department of Prints and Drawings in “Bonaparte and the British: Prints and Propaganda.” This is one of my favorite haunts, with such a host of treasures that they can pull out wonderful things, from Renaissance drawings to modern etchings and engravings, to suit any occasion. (The BM has, apparently, 1,400 satires on Napoleon alone.) For the Bonaparte show, the military historian Tim Clayton and the knowledgeable curator Sheila O’Connell have kept the focus on the long propaganda war, steaming on from the French Revolution in 1789 to the start of the conflict in 1793 and through to the dramatic end twenty years later.

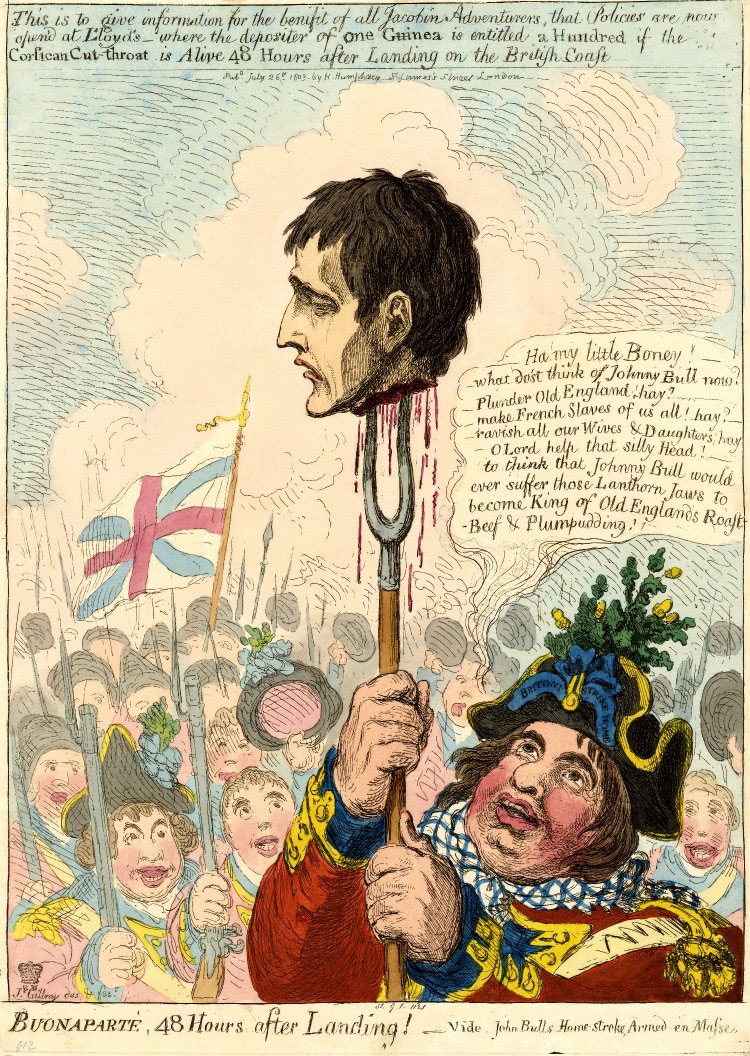

James Gillray is everywhere, with his feverish, fantastical violence, showing John Bull devouring French ships and the Devil toasting a tiny Napoleon on a raging fire. More examples of this can be found in a concurrent exhibition, “Love Bites: Caricatures by James Gillray,” at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. Amid the jokes about mistresses, chamberpots, gout and phallic columns, there’s still plenty of propagandist zest, including the gloating Buonaparte: 48 Hours after Landing!, where Napoleon’s pale head drips gore from the end of John Bull’s pitchfork. That bloody image is also at the British Museum, among the many “down with Boney” prints.

Isaac Cruikshank’s Nelson snaps shut the jaws of the Napoleonic crocodile in Egypt, while Cruikshank’s son George comes into his own at the end of the wars, mocking the contrast between Napoleon’s sanguine bulletins and the reality of the snowbound retreat from Moscow in Boney hatching a Bulletin or Snug Winter Quarters. Other well-known satirists include Charles Williams, drawing Bonaparte as a monster exhibited by the mountebank Pitt at a country fair, and the twenty-year-old Richard Newton, sketching the Pope literally kissing Nap’s arse. Rowlandson, too, is never far away, and his adaptation of a German print, The Devil’s Darling, with the huge, hairy, goat-legged devil cradling an infant Napoleon, is one of the boldest here.

But “Bonaparte and the British” isn’t all cruel, crude, gung-ho roistering. There are anti-British satires, produced by Napoleon’s own efficient propaganda machine. These are often more elegant in line and color than their British counterparts, like Vent contraire, in which British women vainly try to deflect the France invasion fleet by waving their fans, while a terrified officer hides under their petticoats. But the real strength of this exhibition is that it works as a biography-in-images of Napoleon, driving us round the room with him, from Italy and Egypt to his rise to Consul and Emperor and on to Moscow, Spain, Elba, and his eventual fall.

Celebratory prints jostle with satires. Here he stands victorious at Marengo and Austerlitz, and here he staggers through the snows of Russia and slumps, forlorn, after the terrible battle of Leipzig in 1813. It is oddly moving, conveying his charisma and illustrating his lasting fascination. We begin with the glamorous portraits of the dashing young general of 1798 treasured by Bonaparte admirers, and end with images of his exile and death—a display case with rings containing locks of his hair, and one of Benjamin Haydon’s small, brooding paintings of Napoleon Musing on St Helena of 1830, a work matched nine years later by Wellington Musing on the Field of Waterloo.

Perhaps we too should be musing. I feel passionately that nameless soldiers and their families should be remembered, but, although the organizers insist that the bicentennial doesn’t set out to glorify war, it’s pretty grim to cheer a battle that left 12,000 dead and 35,000 wounded. Yet the exhibitions are everywhere. The National Army Museum in Chelsea is coordinating “Waterloo Lives” exhibitions across the country, from Aberdeen to Somerset, Sheffield to Cardiff. In Cumbria, “Wordsworth, War and Waterloo,” at the Wordsworth Museum at Dove Cottage, shows how the wars affected even the sheep-farmers of the northern mountains. Wordsworth himself was a volunteer during the invasion scare of 1803, setting off with the villagers to drill, the kind of rackety crew caricatured here in Symptoms of Drilling.

Advertisement

In London alone one could march from show to show. At Tate Britain, “Fighting History” aims to show how artists help us reflect on history, from large-scale battle paintings to contemporary works. At the Foundlings Museum in Brunswick Square, “Foundlings at War” features two boys who served at sea, alongside stories of children whose fathers died at Waterloo. If this reminds us of the impoverished troops that Wellington dismissed as “the scum of the earth,” at the other end of the spectrum, Wellington’s own Apsley House is re-staging the Waterloo Banquet held each year from 1820 until the Duke’s death. At the foot of the stairs stands Canova’s hefty statue of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker—having commissioned it, Napoleon was aghast to see himself nude and it stayed in its packing case until the British government bought it and the Prince Regent gave it to Wellington.

In the summer that followed the victory, “The great amusement at Bruxelles,” Caroline Lamb told Lady Melbourne, “is to make large parties & go to the field of battle—& pick up a skull or an old shoe or a letter, & bring it home.” (Trophies included “Waterloo teeth” collected from the dead and sold to dentists—some are on show at the Victoria Gallery in Liverpool.) Walter Scott was one of many tourists, aghast at the horrors of modern war. On the battlefield, where so many had been hastily buried, he told the Duke of Buccleugh, the smell was “most offensive”: “The more ghastly tokens of the carnage are now removed, the bodies both of men and horses being either burned or buried. But all the ground is still torn with the shot and shells, and covered with cartridges, old hats, and shoes, and various relics of the fray which the peasants have not thought worth removing.”

Another visitor was Turner, who made detailed sketches and talked to survivors. But his great painting, The Field of Waterloo, of 1818, shows a scene of slaughter rather than triumph. Here the exuberance of all the satirical prints and dashing military watercolors is forgotten. Instead the opposing nations mingle and the divisions of rank vanish, as the women hunt by the light of a flaming torch, to find those they love among the tangled bodies.

“Bonaparte and the British: Prints and Propaganda in the Age of Napoleon” is on view at the British Museum in London through August 16. “Love Bites: Caricatures by James Gillray” is showing at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford through June 21. “Waterloo Lives” is a nationwide program of events, activities and displays through October 24. “Wordsworth, War & Waterloo” is at the Wordsworth Museum in Cumbria through November 1. “Fighting History” opens June 9 at the Tate Britain in London. “Foundlings at War: The Napoleonic Wars” opens June 16 at the Foundling Museum in London. This summer the Apsley House in Bath has a “Waterloo Anniversary Display” while the Wellington Arch in London exhibits “Waterloo 1815 – The Battle for Peace” through November.