In 1991, when I was searching for illustrations for my book Low Life, I stumbled upon the collection of some 1,400 photos from the New York Police Department, dating from 1914 to 1918, that were held in the city’s Municipal Archives: images mostly of crime scenes, of murder victims pictured on the sidewalk or in their narrow bedrooms, often from overhead, with angles so wide the tripod legs appeared to encase the dead. The pictures were so powerful, at once raw and lyrical, that I knew I had to write about them; the result was Evidence, which came out in 1992. There were many mysteries surrounding the photos, some of which I was able to solve and some not. For example, it wasn’t immediately clear who had taken the pictures, but I imagined a single artist was responsible because of their distinct style: the angle, the austere calm, the illuminated bodies surrounded by darkness. Instead they turned out to be the work of at least six people, four of them members of the NYPD’s Bureau of Criminal Identification.

There remained, however, the question of what had happened to all the rest of the pictures. The collection I had seen spanned only five years of decades of activity by the NYPD. What had happened to the possibly tens of thousands of other photos dating from before and after the years covered? John R. Podracky, who had worked for the Municipal Archives and at that time was curator of the Police Academy Museum, told me that the glass plate negatives of the collection I’d seen—there were no original prints—had been found in a small closet under a basement staircase when the old police headquarters on Mulberry Street was being converted into condominiums. He suggested that the rest of the material had been summarily disposed of during the conversion. Perhaps they were resting on the bottom of New York Bay in a pile of broken glass, as had apparently been the fate of the NYPD’s nineteenth-century mug shot negatives when they were jettisoned in the early 1950s.

I soon began to receive letters—as did the Municipal Archives—from hopeful citizens who wanted to know just where in the harbor they might have been dumped; maybe divers could be sent to recuperate them. But there was no proof of what had happened to them (leaving aside the question of how photographic emulsion would survive even a brief immersion in water), and the police department would neither confirm nor deny. The question simply hung in the air until about three years ago, when Michael Lorenzini, the Deputy Director and Curator of Photography at the Municipal Archives, received a call from the NYPD. The caller wanted to know whether he could help them figure out how to dispose of a roomful of photographic material stored at One Police Plaza; the department needed the space.

The room, the size of a large walk-in closet, was jammed to the ceiling with filing cabinets and boxes—250 cubic feet worth of material—and it reeked of vinegar. Lorenzini (who had previously brought to light the work of the great but unsung Eugene de Salignac, chronicler of the city’s bridges and structures from 1906 to 1934) spent weeks in the room, in a hazmat suit with breathing apparatus; when he took the subway home at night, people moved away from him. The odor came from the decay of acetate negatives; there were also many nitrate negatives, some of which were so corrupted they had to be disposed of immediately—nitrate still negatives are not quite as dangerous as nitrate motion-picture film coiled in metal cans, which is known to spontaneously combust, but almost. The room also contained many more recent polyester negatives, as well as some 2,000 glass plates and nearly two dozen boxes’ worth of prints. The final yield amounted to about 180,000 images from perhaps 50,000 cases, ranging from an uncertain point prior to 1914 all the way to 1972. In March, the National Endowment for the Humanities announced a grant of $125,000 to the Archives, to allow digitization of 30,000 pictures.

I recently visited Lorenzini at work. There wasn’t much immediate sign of the scope of the job—the surviving nitrate and acetate negatives are being stored in five freezer units in Brooklyn—but there was enough to suggest its outlines. The numbers are fairly dizzying; Lorenzini and his colleagues have thus far inspected about 80,000 images, less than half the total. Nevertheless, they can account for almost sixty years’ worth of cases, from the strictly banal (burglaries, say) to the very high-profile, such as the assassination of Malcolm X at the Audubon Ballroom in 1965, which was covered extensively, in part with color film, which was still rarely used at the time.

Advertisement

There are some non-photo items, such as a box of evidentiary matter treated to enhance fingerprints; these include the lid of a cigar box and an insinuatingly threatening letter sent to a newspaper columnist in the 1920s. There is a box of prints of stand-ups—booking photos not unlike mug shots, but that show the suspects at full length—taken in Brooklyn in the 1920s. (The haul is largely material from the Manhattan Photo Unit; the Brooklyn unit mostly kept its files separate. Sadly, those files, which no archivist had ever laid eyes on, were lost in flooding during Hurricane Sandy, in 2012.) There are folders of prints that show subjects of enduring significance, such as rallies in the 1930s by Nazi-affiliated groups, the Harlem riots of 1964, and an assortment of street demonstrations during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Many of the period prints date from the 1920s. As Lorenzini and I chatted, I slowly made my way through a box that contained cases running roughly from May to November, 1926. I was assisted in my perusal by the photo unit’s blotter for the period, a massive ledger in which every case is logged and described, the summations conveying a dry, hard-boiled tone:

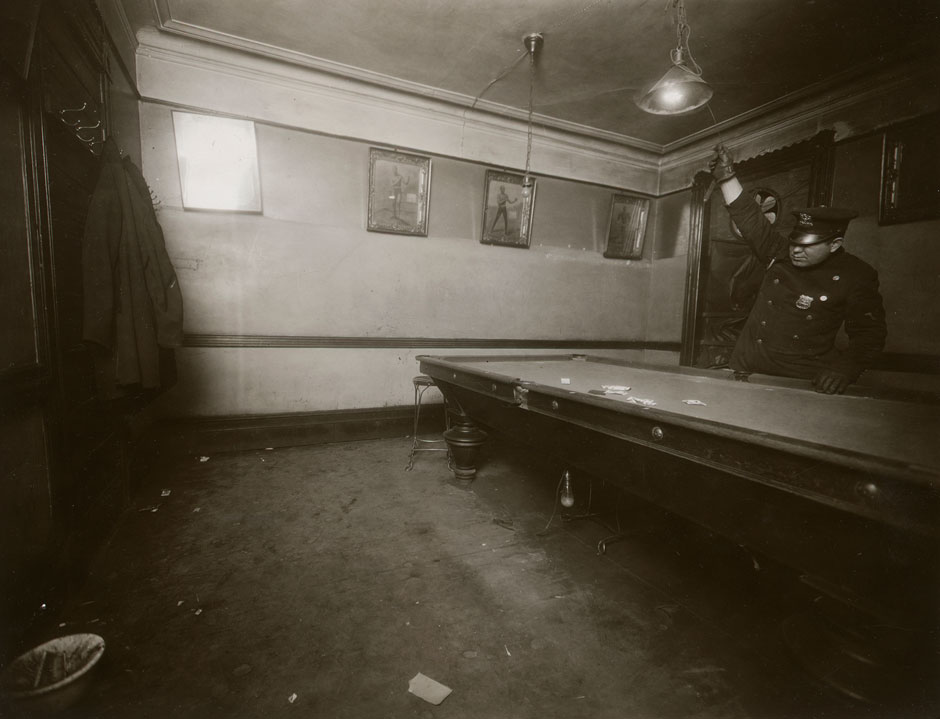

Pool room showing bloodstains on wall. 107 West 132nd Street, second floor. November 23, 1926. James Congers stabbed to death, allegedly by Ralph Brown, no arrest.

The one blotter that Lorenzini could not locate was the first, which would have covered everything prior to 1925 or so, which means among other things that the dates of the earliest pictures can only be conjectured. The cases were numbered sequentially, at least at first; since case 599 dates from April 1914, for example, and 708 from June 1915, the earliest surviving pictures, which are in the single digits, might go back to 1910 or even farther, although Lorenzini is loath to speculate.

The 1926 photos have much in common with their counterparts from the previous decade. Police photographers—who included a few of the same people—were still employing bulky plate cameras, using wide-angle lenses (although perhaps not quite as extreme as in the earlier pictures), and lighting with magnesium powder. The slow decay of the flash, combined with the length of the exposures, softened edges and created penumbras, which goes a long way toward explaining the otherwise unaccountable lyricism of these images of death and destruction. Much of the subject matter is likewise familiar: murders, suicides, a few burglaries. Nevertheless, times have clearly changed. There are multiple car crashes, subway accidents, raids on speakeasies and gambling clubs, and, overwhelmingly, illegal stills. During Prohibition, bootleggers erected stills in all sorts of places, but particularly favored abandoned houses, where a still might be positioned—awkwardly—behind the door of an apartment, perhaps tall enough to poke through the ceiling to the floor above, with tubing running into closets.

The pictures are of undeniable photographic significance. Not every one is a masterpiece, but all display patient craftsmanship in their framing and lighting, making them seem lapidary, even definitive. Every picture is a tableau, complete unto itself. In addition, besides preserving the physical facts of important events and highlighting trends and aberrations in social behavior over the decades, the pictures record innumerable details of the appearance and atmosphere of the city in those decades. From them you can learn what kitchens looked like, how grocery stores decorated their display windows, how much trash accumulated in the street, what hazards attended the operation of open-top flivvers, and all about the wild variety of social clubs, illicit and otherwise, fancy or outré or irredeemably basic, that occupied an awful lot of the real estate in any era. They provide a vital and even visceral link to the city’s past, at a time when three-dimensional remnants of that past—buildings, along with their occupants—are being eliminated every day.