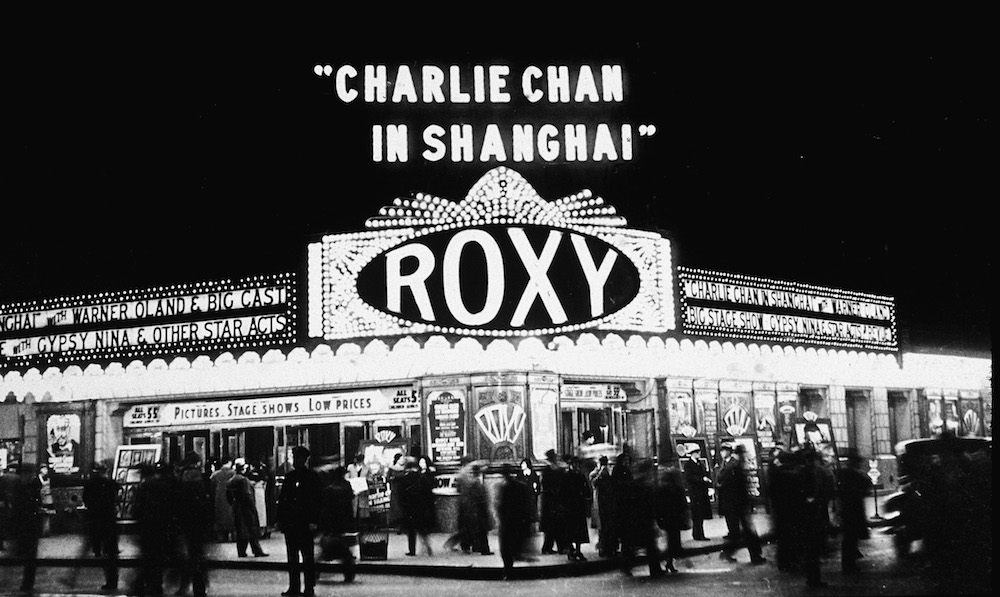

The Rockettes, when they first became famous, were called the Roxyettes. Named after the impresario S.L. “Roxy” Rothafel, they were a regular act at Rothafel’s Roxy Theatre, which opened in 1927 on 50th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues. In the Roxy’s lobby—a five-story rotunda—marble columns surrounded the world’s largest oval rug. The main theater had nearly 6,000 seats. On opening night, Rothafel projected onto the cinema screen letters of congratulation from President Calvin Coolidge and the mayor of New York, Jimmy Walker.

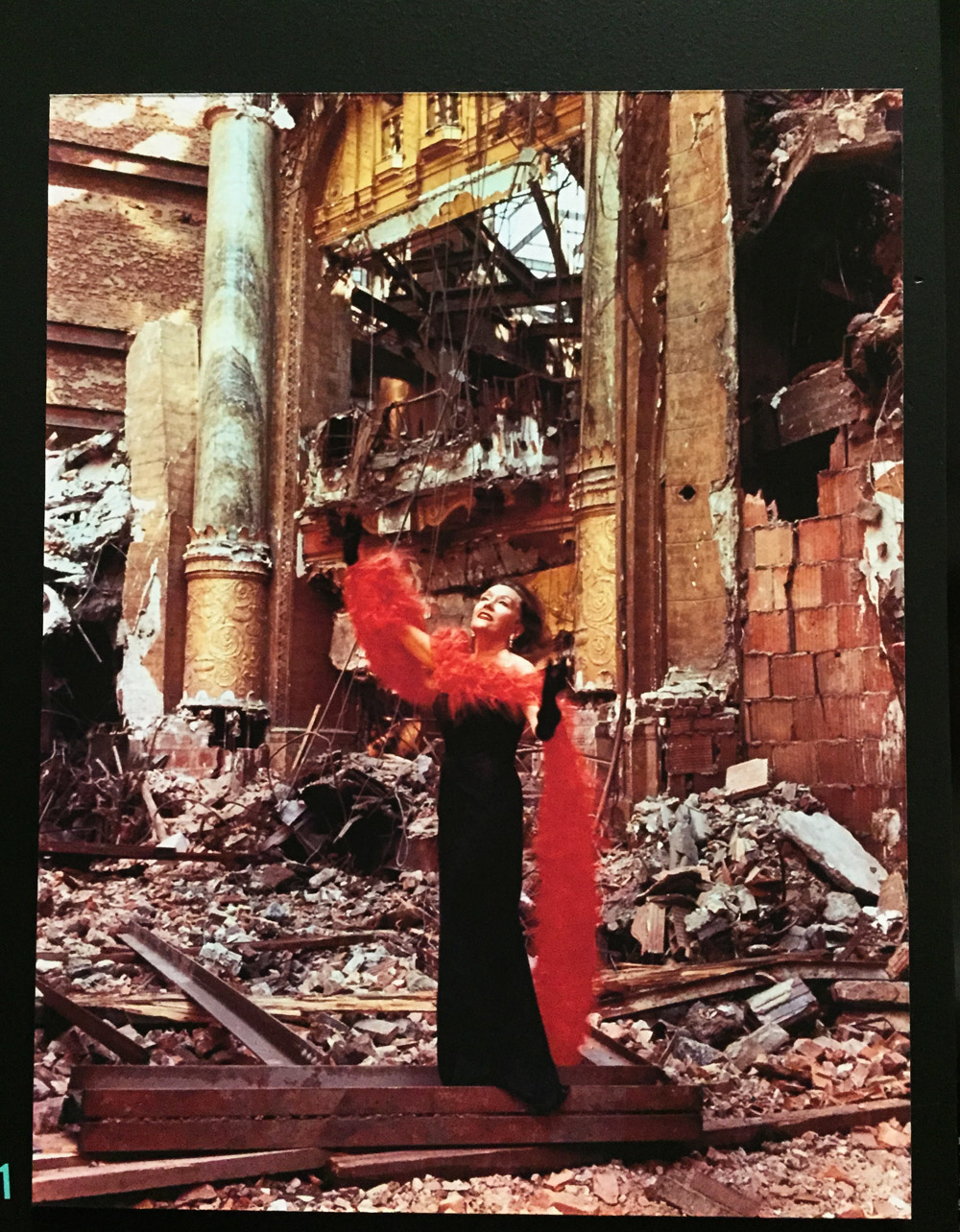

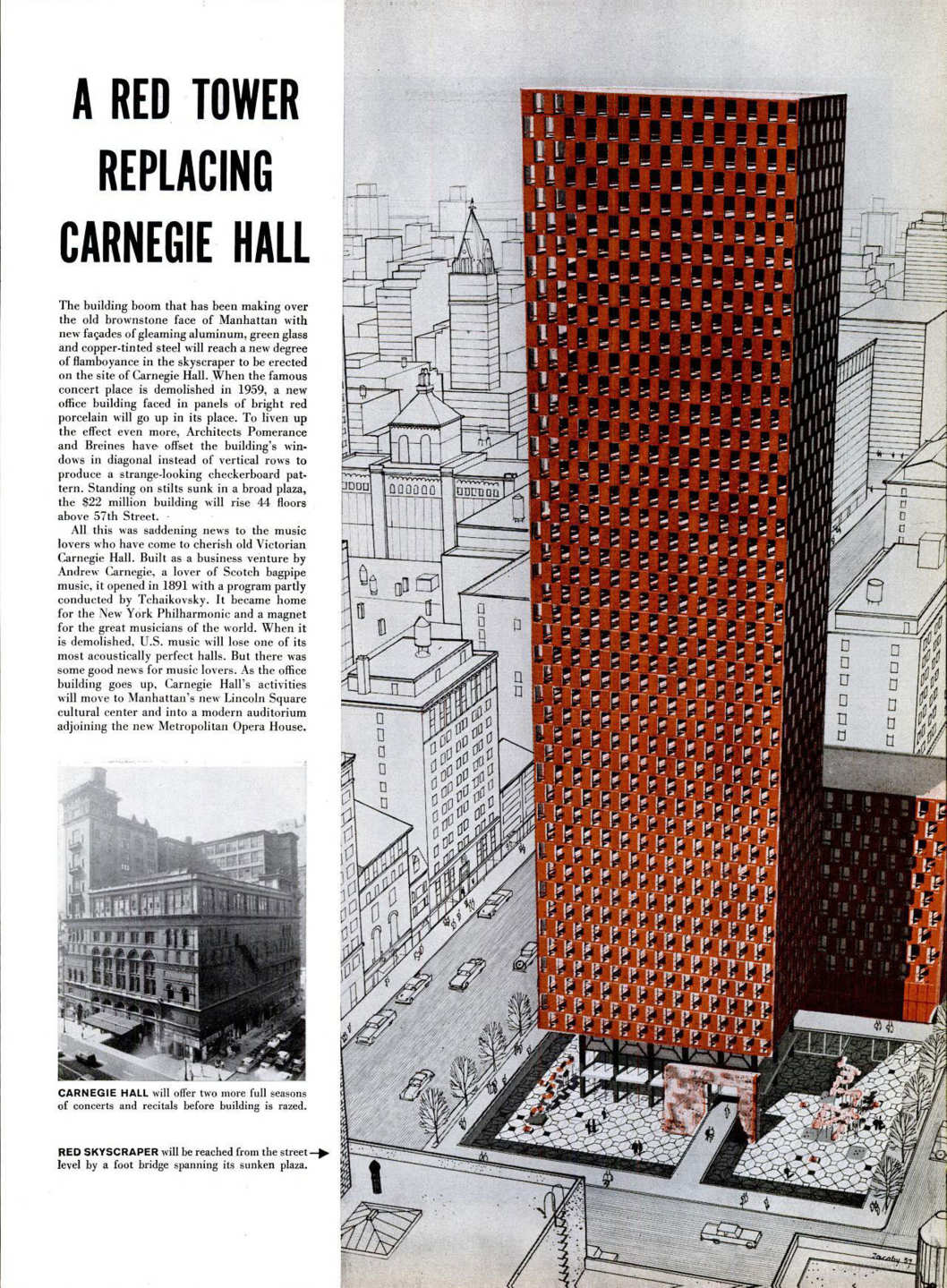

In 1960, the Roxy was unceremoniously razed to make way for an office building. It was just one of many urban erasures that led to the establishment in 1965 of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. The story of the agency’s emergence as a powerful force in city politics is documented by a revealing new exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York, “Saving Place: 50 Years of New York City Landmarks.”

Today in New York there are more than 1,300 individual landmarks, and 114 historic districts encompassing some 33,000 landmarked properties. Other landmarked sites include about a hundred lampposts, seven cast-iron sidewalk clocks, three Coney Island amusement park rides, and a Magnolia grandiflora tree planted in Brooklyn in 1885.

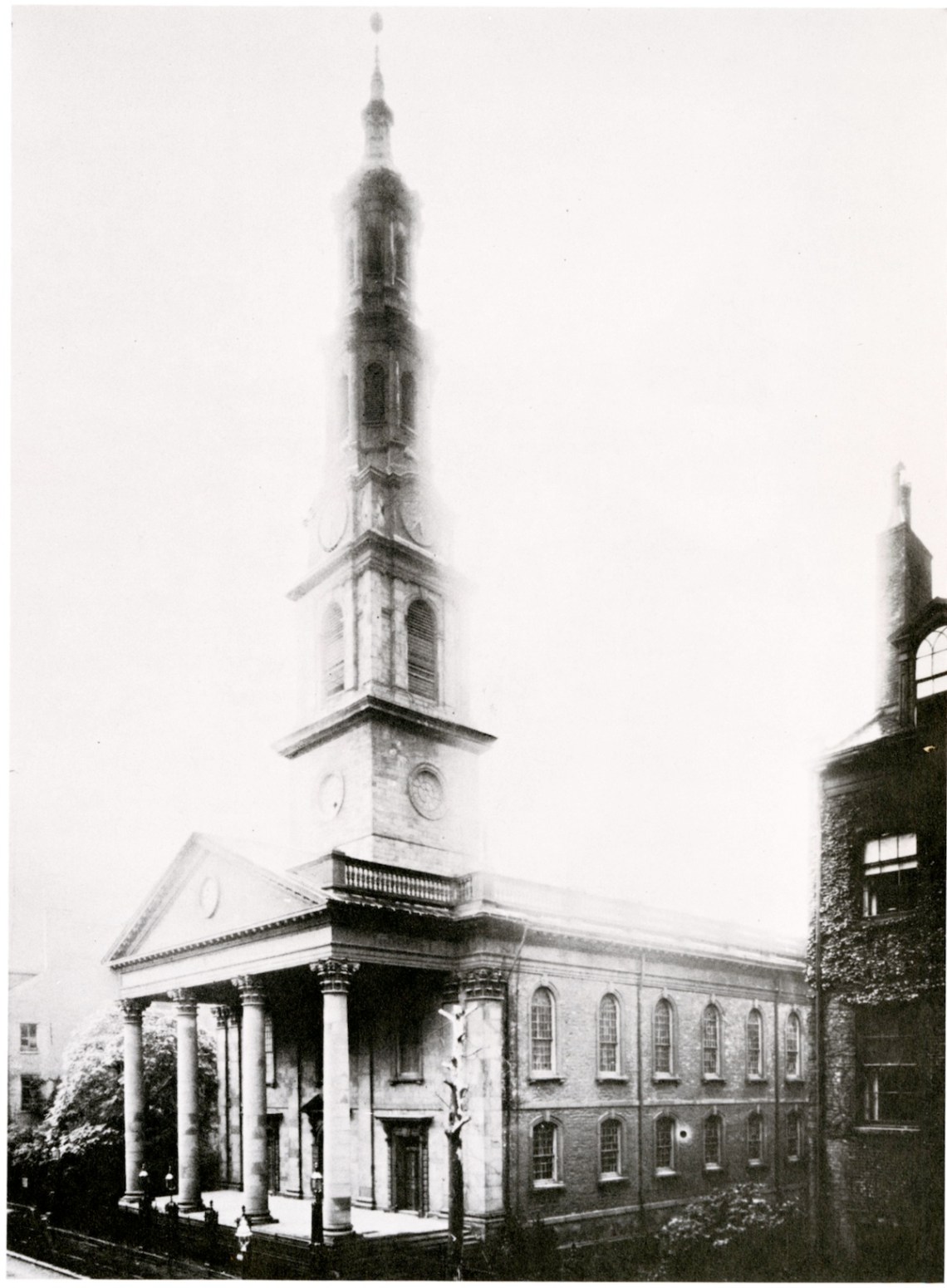

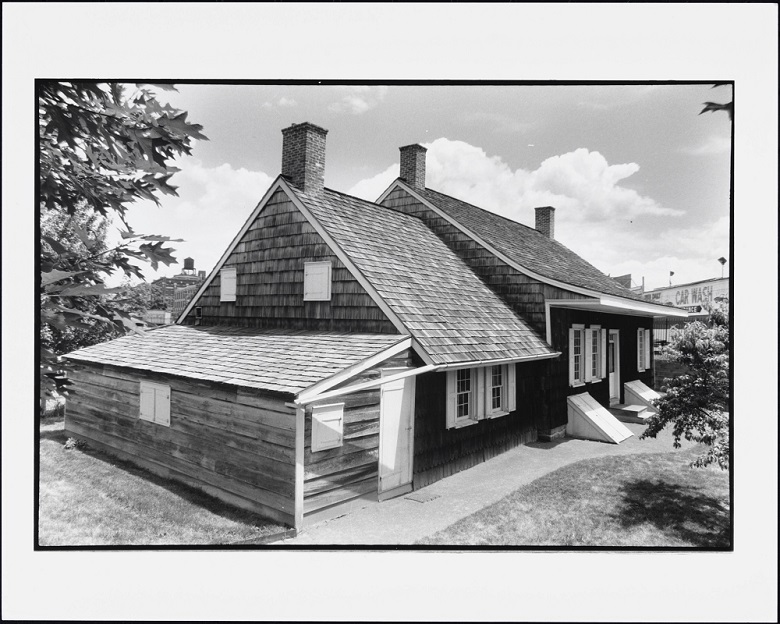

Yet prior to the landmarks law there was no legal means for protecting historic sites like the Roxy. Many had fallen into disrepair. A 1965 photograph in “Saving Place” shows Brooklyn’s Wyckoff House—a single-story wooden frame home built in 1652, and New York’s oldest structure—with a large hole in its roof. It was nearly demolished in the early 1950s to accommodate the construction of a new street. The Wyckoff House survived long enough to be the first building designated for preservation by the Landmarks Commission. But it took the destruction of many beloved places before the law gained the political support it needed.

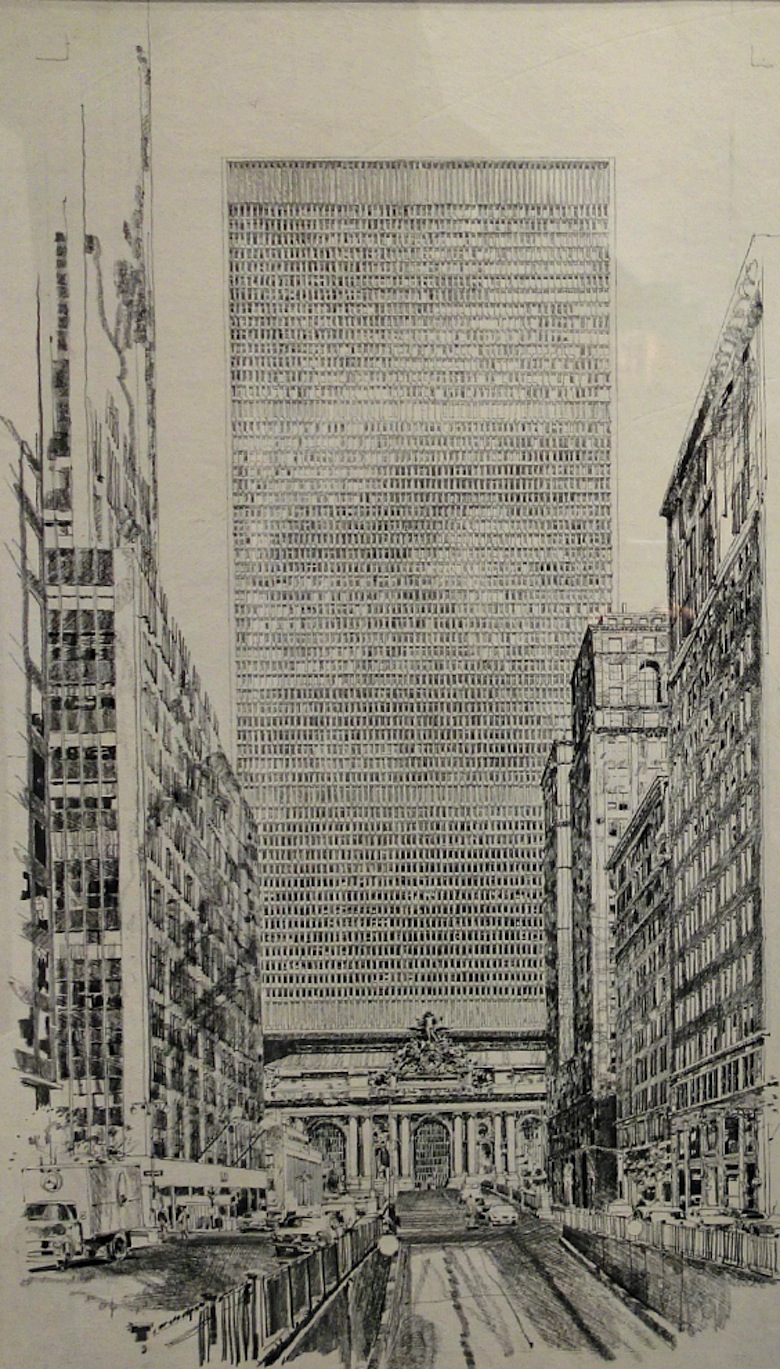

Nothing angered New Yorkers more than the demolition in 1963 of Pennsylvania Station, McKim, Mead & White’s Beaux-Arts masterpiece, and the exhibition contains a good deal of ephemera from the resultant protest movement. Writer and reformer Jane Jacobs and architecture critic Aline Saarinen are pictured picketing in white gloves and pocket books. A collection of pro-preservation lapel pins display slogans like “REMEMBER PENN STATION,” “I AM A FRIEND OF CAST IRON ARCHITECTURE,” and “Terra Cotta…It’s Out of Sight!” A photograph of an important political meeting shows Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, New Yorker critic Brendan Gill, and former Mayor Robert Wagner sitting around a table at the Grand Central Oyster Bar.

When the landmarks law finally did pass, it granted the agency it created broad powers, not only to preserve individual buildings but also to establish “historic districts” in which all changes to existing structures, and especially all new structures, would be tightly regulated. The law’s constitutionality was challenged until a 1978 Supreme Court ruling. In a 6-3 decision approving the preservation of Grand Central Station, Justice William J. Brennan wrote in support of ”a widely shared belief that structures with special historic, cultural or architectural significance enhance the quality of life for all.”

The exhibition catalog goes further. In one essay, Charlotte Braudy, a co-founder of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Society for Historic Preservation, makes the case for designating Bedford-Stuyvesant as a historic district. Bed-Stuy is one of many neighborhoods in Brooklyn experiencing rapid demographic change and condo development, and Brady argues that landmarking would protect both the neighborhood’s nineteenth-century row houses and its inhabitants’ “way of life.”

Quite the opposite argument has also been made in an ongoing debate among planners and academics in New York. A 2014 report published by the NYU Furman Center indicated that a historic district designation often increases property values and reduces the construction of new housing. One of its authors, the conservative Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, has argued that landmark designation “increasingly makes those districts exclusive enclaves of the well-to-do, educated, and white.” This is exactly the situation that longtime African-American residents of Bed-Stuy hope to avoid; yet Brady, like the rest of the writers in the catalog, does not substantially address the effects of historic districts on the housing market. In its determination to celebrate the landmarks law, “Saving Place” can seem to leave the most difficult questions unasked.

Advertisement

But the sort of city we would have without the landmarks law is clear from the fate of the Roxy. Today the old theater is a T.G.I. Friday’s.

Saving Place is on view at the Museum of the City of New York through September 13.