Charles Simic: There’s been a lot of talk lately in connection with the death of Ornette Coleman about a number of New York jazz clubs in the early 1960s. I was just out of the army in those days, trying to restart my life, working during the day, attending classes at NYU at night, getting married, and only now and then catching a late set at the Five Spot, Village Vanguard, or some other club in the Village. I had no idea you were hanging out with Ornette.

Milan Simich: I met Ornette Coleman in a loft on Cooper Square in 1964. That’s where LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and others lived. There used to be jam sessions there. I think the building is still there. It was a double bill: Archie Shepp’s band and Pharaoh Sanders’s band. I think it was a buck and everybody sat on the floor. I had bought Ornette’s albums even before coming to New York, while still in high school. I remember buying his first album, Something Else!!!!, at Jack Howard’s Record Store on State Street in Chicago in 1960, I think it was. At the same time I picked up a record by Chu Berry, who was a great swing tenor player and the polar opposite of Ornette. The saleswoman, a black lady with short, red-tinted hair, said “You have very good taste, young man.” I was fifteen years old, had been into jazz for a year.

So here I am at this loft four years later and who’s sitting opposite me but Ornette Coleman with a good-looking lady. Between Archie and Pharaoh’s sets somebody put on the Eric Dolphy-Booker Little Quintet At the Five Spot record. There’s a Booker tune aptly titled “Aggression” where twice he does this smeared notes thing and at that moment our eyes met across the room and we both broke out laughing. Me and Ornette. Two guys diggin’ jazz on the Bowery in 1964! After the gig he gave me his address and invited me to visit. About a week later on a Sunday afternoon, I went to the West Village. I forget the street, he had a basement apartment. I hesitated, couldn’t ring the bell, and walked away. Thing is, I was nineteen, what was I going to talk to him about? Next year I finally heard him live at Village Vanguard. I lived near the club at the time so I went a lot during what I think was like a three or four-week gig. I would sit by the drums and when Ornette would come out of the dressing room and come to the stage, we would say hello. Ornette had this thing, this lick. He repeated this phrase over and over, quicker and quicker on up-tempo tunes, and stop. It was like being hurtled toward a precipice and stopping on the edge. Loved that.

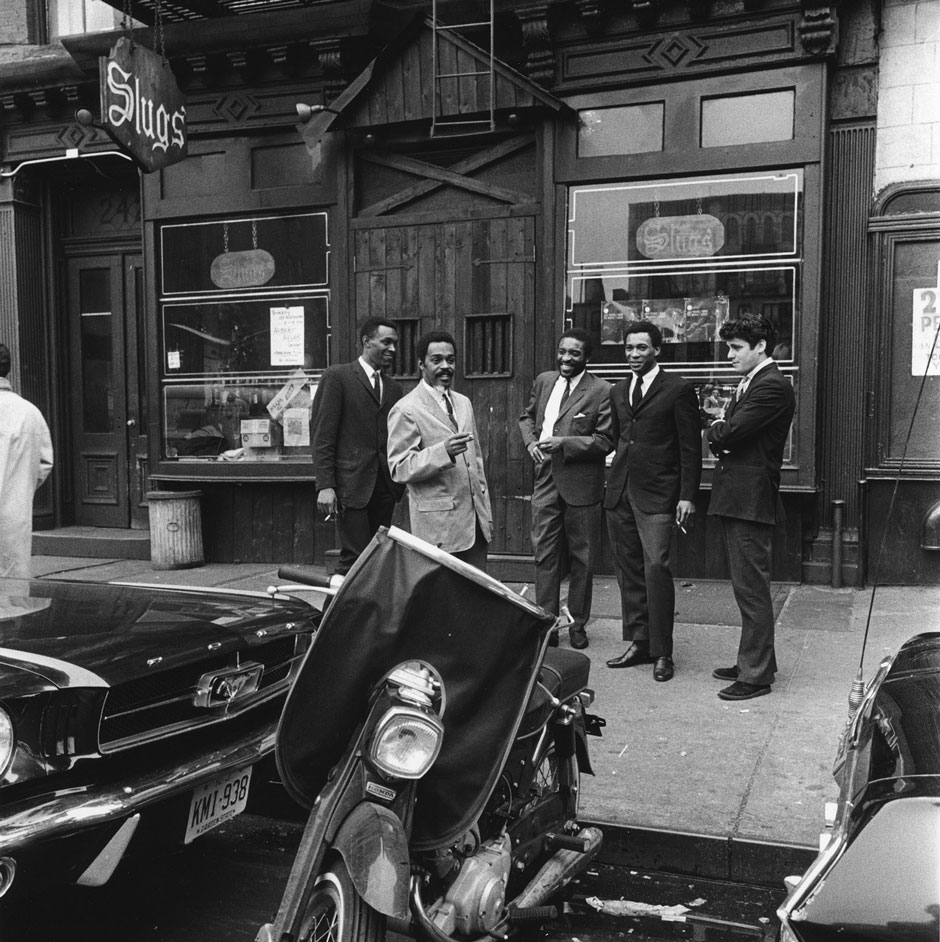

Charles: Tell me about Slug’s, that much-loved and famously dangerous place on East 3rd Street between Avenues B and C. Though I went to clubs in the Village, I ventured there only once to hear Sun Ra and remember being scared walking from Astor Place and being petrified walking back after midnight. You told me you went a lot, so I wondered what it was like.

Milan: Slugs’, not the singular possessive Slug’s, which is always mistaken. Originally it was Slugs’ Saloon, but the Liquor Authority didn’t allow the name “saloon” to be used. So it became, on those famed posters, Slugs’ In the Far East because of the address, 242 East 3rd Street. The name derives from the spiritualist George Gurdjieff’s term for human beings and how they go through life in a state of waking sleep… slugs. The two original owners, Jerry Schultz and Bob Schoenholt, were in the same Gurdjieff group as our father. Story goes that Jerry just wanted to open a bar for the artists that lived in the hood, but Hank Mobley, the tenor saxophonist, lived in the building and persuaded Jerry to put in music. You’d walk into this long, narrow, storefront-size room with the bar to your left. At the end of the bar, against the wall, was a small stage with an upright piano that could fit drums, bass, and one soloist. Opposite the stage were a few tables, with the rest of the tables in the back. There was also a jukebox against the wall opposite the bar before you came to the tables. When it became popular, they built another stage in the back and got a baby grand and you could fit either a quintet or Larry Young’s B-3 electric organ.

Charles: What made the gigs at Slugs’ stand out in those years? What was so different from other jazz clubs?

Advertisement

Milan: Slugs’ was “different” because it was on the Lower East Side and was the latest embodiment of the avant-garde culture that that area was producing. By the mid-1960s, the Beat vibe had gone out of the Village. Bleecker Street, the coffee houses were just tourist destinations. The East Village as it became known was where the arts were happening; all the painters, writers, poets, musicians, Ellen Stewart’s La Mama, The Living Theater. The Saxophonist Jackie McLean was in Jack Gelber’s Living Theater production of The Connection as an actor and also playing on stage. Actually, if you see Shirley Clarke’s filmed version of the play with Jackie, you can see the scene back then. The cold, dirty lofts, roaches, general bleakness. But you could live cheaply. I paid my rent, food, working as an office boy and had money left over to go to clubs or the opera. Just Google St. Mark’s Place and see who lived there through the years. Leon Trotsky lived at 80 St. Marks Place, where the Jazz Gallery was and where Sonny Rollins made his comeback, John Coltrane started his own group, and Ornette played with Dizzy. Years later, when Slugs’ had become a bodega, I went in and was stunned how small the place was and just how much great and important music went down there. Slugs’ kept acoustic jazz going in those dark days of Beatles, The Twist, and Fillmore.

Charles: That’s the reason I went that one time. I wanted to take father along because of Gurdjieff, but figured that Sun Ra’s “The Solar Myth Arkestra” or the “Blue Universe Arkestra,” as his groups were called, might be too much for him. I had heard there was a waitress who wore a live boa constrictor over her shoulders as she went around serving her customers and that there were frequent fistfights at the bar or outside in the street, but I saw nothing like it that night. When did you go there first?

Milan: I had read—I guess in Down Beat—about this club. I went on a Sunday afternoon. It was the free jazz pianist Paul Bley with David Izenzon on bass and Charles Moffett on drums. It was an upright piano. I only stayed a few minutes. It was 1964 and I didn’t like the area cause it was an immigrant neighborhood and myself being one, didn’t feel I needed to be around that. Slugs’ was a dangerous place—lots of muggings and fights. It closed in the early 1970s, not long after the great trumpeter Lee Morgan was shot and killed there by his common-law wife. But, it was Jackie McLean who made me a somewhat regular at Slugs.’

Charles: What about Jackie McLean?

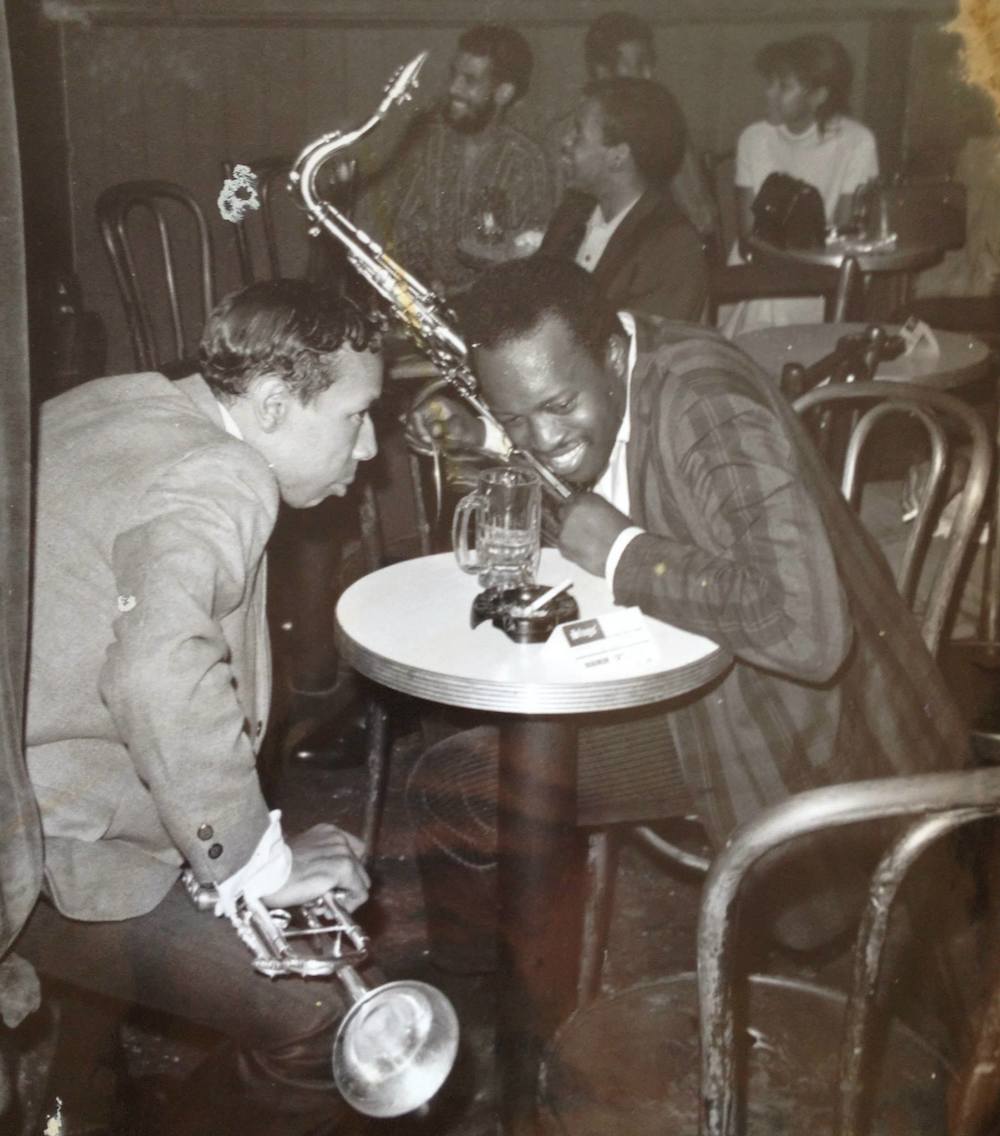

Milan: What I liked about McLean’s music that it was all in your face. He was off the scene cause he didn’t have a cabaret card, drugs or something. He could work concerts or Sunday afternoon sessions when a cabaret license wasn’t required. It was the One Step Beyond record band with Grachan Moncur, Bobby Hutcherson, Eddie Khan, and Clifford Jarvis. Shortly after, he did a series of Sunday afternoons at a restaurant on Waverly Place in one of the NYU buildings, Harout’s. Hutch was on vibes again and it was the first time I heard Charles Tolliver, Cecil McBee, and Jack DeJohnette.

But later that year Jackie finally got the cabaret card and was booked into…Slugs’. When Jackie started playing there he and his wife Dolly also opened this soda fountain/candy store a couple of storefronts up. The whole family worked there. Jackie was brusque. He had, like many others who were street wise, a wariness toward people. He was opinionated, but not like Mingus, who believed in every conspiracy theory that had been handed down through the ages. And he was not hesitant to tell you the latest one in the middle of a set at the Five Spot.

I got to know Jackie well years later. He told me about his first time playing at Birdland. It was 1952 or something, with Miles Davis. The very first solo he took that night, he was so nervous he stopped, turned around and went back through the curtain at the back of the stage and into the dressing room behind it and threw up. Oscar Goodstein, the Birdland manager, ran in and yelled at him, “Get back on stage!” Jackie goes back out, finishes his solo and gets a big round of applause from the audience. Miles turns to him and says, “Man, I’ve never seen that one before!”

Advertisement

Charles: Now and then sitting in a packed club and hearing someone like Thelonious Monk or Sonny Rollins, I recall thinking, this is heaven. I had in mind both the music and the spectacle—like that time Sonny started playing in the bathroom at Five Spot while his bass player, drummer, and pianist were waiting for him on the stand. But the lofts were more your thing. I went to poetry readings in lofts and a couple of happenings, but don’t believe I heard any music or the jazz musicians you admired.

Milan: I don’t want to mythologize the loft scene. It was just another scene like all before and since where people congregated around a common interest. This was one about music, brand new music, improvised, instrumental music that had no connection to the melodic, rhythmic structures of what was then—the mid-1960s—commonly accepted as jazz. Without guideposts, you had to be open to the overall sound, shape, contours of the music being played. You either liked it or not. I dug it. In lofts you could stand or sit next to the band, there were no microphones, everything truly acoustic, and no drinks bullshit. Everybody was there for the music.

There was The Cellar or something off Broadway in the nineties that had a run of Sundays. I heard Sun Ra with the wonderful John Gilmore on tenor there. And that gig with Cecil Taylor and Tony Williams, an all-nighter in a loft on 4th Avenue and 10th Street, that also included Ra, Archie’s group, and Paul Bley’s Barrage band, which I also heard at The Cellar. I dug that band cause of the bassist Eddie Gomez, who played with the pianist Bill Evans for many years. My sole claim to fame in my extremely brief and sad attempt to play bass was being asked to replace Eddie in the band one night.

Charles: By the way, what ever happened to that bass?

Milan: The first one which I bought in a pawn shop in Chinatown was my “attempt.” When I went home after having dinner with you and Helen on 13th Street during the blackout in 1965, I got on top of the bed and played it for hours, since there were no lights, except the moon and complete silence everywhere. I don’t remember what I did with it, sold it or left it out in the street. As you know, I had other things to think about. In December of 1965 I was drafted into the army and sent to Vietnam.