The other day, a man stood near the middle of a half-empty New York City subway car. In a reedy, solitary voice just loud enough to be heard over the grind of the moving train, he said to his fellow passengers,

I’ll be honest with you, I smell bad. My deodorant and my soap, they were stolen from my bag while I was sleeping. I spent the night on the A train. I got tossed out of Starbucks because a customer complained of my odor. I don’t blame her. I hate to smell like this. I don’t want to be with myself when this smell sticks to me. It’s my own fault. I’m asking you to forget about why I’m in this state and just listen to what I’m asking of you. I want to take a shower. It’ll cost me thirteen dollars to take a shower.

There was no rage-camouflaging cry of self-pity, no story of personal injury, of a lost job, of eviction from an apartment, a ruinous lover, imprisonment, assault, or rape. He was simply giving the facts. And the facts were that on the ladder of homelessness he was nearing the bottom rung. The odor that has passed the threshold of tolerance, that makes you a pariah even among those who have been cast out of their homes, had settled upon him. Although most everyone in the subway car seemed moved, all but one shunned even the split-second contact necessary for the transfer of a few dollars or coins.

In February, the number of people sleeping in New York City’s municipal shelters topped 60,000, the most since the Great Depression, and up 79 percent from ten years ago. On a random night last May, there were 24,014 children in the city’s shelters, 21,832 “adults in families,” 9,719 single men, and 3,341 single women. Fifty-seven percent were African-American, 31 percent were Latino, and 8 percent were white.

Unfortunately, these numbers can be expected to rise. As is already well known, hundreds of millions of dollars of new real estate capital has been flowing into large areas of central Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx—investment on a scale that has not been seen for nearly a century. Some of this has been for new developments, increasing density in formerly industrial pockets that have been upzoned, as realtors put it, for residential use. But, having identified deep outer borough neighborhoods as being “undervalued,” private equity funds with access to large amounts of capital from passive, non-meddling investors have begun buying older buildings consisting mainly of affordable, rent-regulated apartments.

The spike in prices has profoundly altered the psychology of these neighborhoods, threatening the security of thousands of long-term residents, many of them families with working parents. The transformation has been dizzyingly abrupt. The process of repopulating a neighborhood with a wealthier class of residents that took twenty years on the Lower East Side during the late 1990s and early 2000s can now occur in five years or less in some parts of Brooklyn and Queens.

In August 2013, for example, Burke Leighton Asset Management bought 805 St. Marks Avenue, a pre-war, six-story building with two hundred apartments in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, for $22 million. In May, a little more than a year and a half later, they sold it to a Swedish real estate company called Akelius for $44 million. Akelius’s CEO said that he decided to invest in Crown Heights when he saw an increasing number of young people with “single-speed bicycles” in the neighborhood. I’ve no knowledge of Akelius’s plans for the building, but the only sure way to derive a reasonable return from this level of investment would be to find a means to deregulate the rent-stabilized apartments, and this invariably involves dislodging the families who live in them.

Over the past fifteen years New York has lost more than 200,000 units of affordable housing—20 percent of the current stock. The rate of loss has accelerated in recent years, putting the future of the city’s remaining rent-regulated apartments in grave doubt. What becomes of a city that economically bars its working class from living in it? New York may be in the process of finding out. Once apartments become deregulated, they never come back.

Where do the dislodged go? And how many are there? Aside from the 60,000 in the shelters, untold numbers of people live on the street. Official estimates hover at around 7,000, but the city is known to under-report the number of street dwellers, which, in any event, is almost impossible to count accurately. To this we may add the unquantifiable number of families who move in with relatives or friends, couch-surfing or paying for a bed or simply a space on the floor. Then there are those who drift away from the city after losing their homes, or are resettled by the state, to Newburgh or Poughkeepsie or Troy in upstate New York, or to places further afield—America’s smaller, post-industrial “ghetto cities” with lots of cheap rundown housing and almost no economic opportunity. Right now, there are probably more than one hundred thousand displaced New Yorkers, the equivalent of a refugee crisis by any international definition of the term.

Advertisement

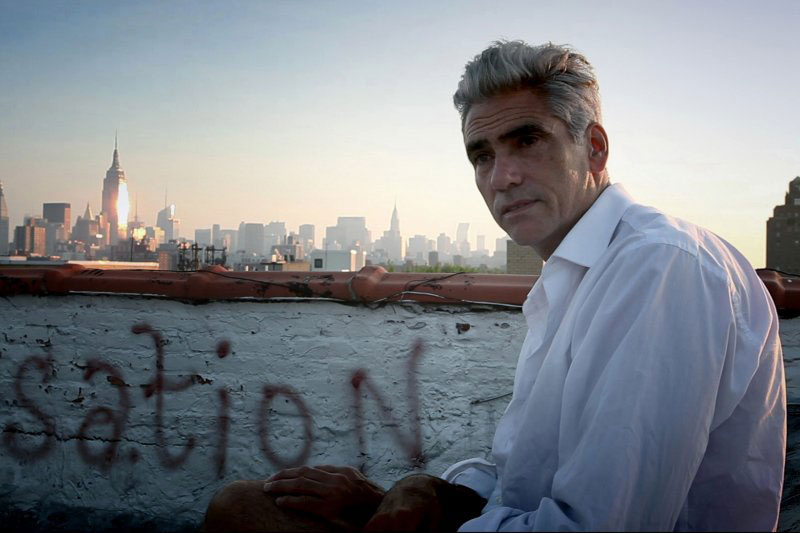

A new documentary, Homme Less, opening on August 7 at the IFC Center in Manhattan, is a reminder of how far the homeless population now reaches in New York. Filmed over a period of two years, the movie follows the life of a former fashion model, Mark Reay. Tall, lean, with a fortunate head of gunmetal grey hair styled to look somewhere between Anthony Bourdain and Karl Lagerfeld, Reay is by any measure perfectly sane. A gap between his front teeth gives him an air of goofiness when he smiles, and in his voice you can hear the unmistakable dissonance of a New Jersey whine. (Reay grew up, lower middle class, near the Delaware Water Gap in New Jersey.)

In 2007, Reay accepted from his landlord a certified check for $30,000 to surrender his apartment on the far western reaches of 22nd Street in Manhattan. What Reay sold was not labor or goods, but his legal right to the state’s protection in his rented home. He had been living in the apartment since 1995.

This sort of buyout is one of the most common routes to homelessness in contemporary New York. There are many strategies that landlords use to persuade a tenant to accept a buyout: withholding hot water and heat, refusing to do repairs, hiking the legal rent with “fees” and increases based on inflating the cost of capital improvements done to an apartment, engaging in noxious around-the-clock “construction,” dragging tenants to court on frivolous charges such as having a roommate or a pet or putting up bookshelves in violation of a lease that prohibits physically altering an apartment. Another common tactic is the use of “preferential” rent, when a landlord charges a long-term tenant less than the legal regulated rent, then slaps the tenant with a large retroactive increase that the landlord knows she cannot afford, forcing her (and her family, if she has one) to leave.

Dozens of bought-out tenants have told me of being worn down by their landlords, of suffering from insomnia and anxiety, of not being able to bear living in a constant state of war and finally capitulating to a buyout just to be done with it—though the buyout is almost never enough for the tenant to resettle in a comparable home.

It isn’t clear in Homme Less why Reay accepted his landlord’s money, but the implication is that the cash was too enticing to refuse. “Within a month I was in Rio,” he says.

Not long after, he is back in Manhattan, the only place where he knows how to cobble together a living. His new digs are the half-hidden fire-escape hanging just below the flat tar roof of a walk-up building on the Lower East Side. A friend of Reay’s lives in the building; Reay has managed to get a copy of his front door key and, without the friend’s or anyone else’s knowledge, has built his nest. The elements of his home are a heavy duty plastic tarp, a bottle of water, a urine jug, clamps, a thermal vest, a black woolen watch cap of the kind burglars wear because it makes his face less vivid, and a weatherproof bedroll. At the time the movie is being shot, he has been living there, undetected, for three years.

Reay enters the building like a fugitive—hyperalert and anxious, his every move geared toward concealment. If he hears footsteps coming down the stairs, he rushes out before he can be seen, waits for the person to leave and reenters. If someone comes into the lobby behind him, he quickens his pace, so “I get a good lead on him.” Pure chance has kept him from being trapped between simultaneously descending and ascending tenants. Polite conversation with tenants throws him into a state of high alarm. Innocent questions—How long have you lived here? Who are you visiting?—take on the aura of an interrogation that could lead to a wrenching disruption of his existence.

When all is clear, he tiptoes rapidly through the narrow lobby and bounds up the stairs. During winter, he pauses near the top landing and, with the quickness of an actor changing costumes between scenes, armors himself in layer upon layer of clothing that he pulls out of his backpack. Then he steps out into a freezing howl and crawls under his wind-thrashed tarp. “I feel like a wild animal,” he says, “a mouse sticking his head up. Because if someone sees me, I’m screwed.” Humankind’s greatest invention, he jokes, would be a tent that looks like a dumpster, because then he would be able to sleep in it in Tompkins Square Park undisturbed.

Advertisement

By allowing the filmmaker to follow him around, Reay has, of course, increased the risk of being discovered. The director, Thomas Wirthensohn, an Austrian, is also a former model; he knows Reay from their working days in Europe and the two men seem to share a kind of collegial fellowship. Homme Less is Wirthensohn’s first film and there is no doubt that his subject is in control. Watching it, you have the sense that Reay has agreed to expose his life because he takes pride in his survival—his wiliness—and believes that he deserves to be admired, as certain extreme outdoorsmen and endurance athletes are admired.

On the street, dressed in his two-hundred-dollar caramel brogues that “look like money,” he appears to shun the homeless as one would the contagiously diseased. He has no way to cook for himself, but we never see him at a food pantry—to join the supplicants publicly lining up for a free meal would be to admit to a condition that he doesn’t believe has befallen him. At one point, he walks past a group of people feeding empty cans to a dispensary machine in order to redeem the deposit. Reay appraises them with a look of sobering dread and continues walking.

As Reay sees it, he is “saving a lot of money. I don’t mind it. I know it’s odd. But I feel like a survivor.” In his more optimistic moments, he presents his homelessness as a daring act and even as a kind of privilege. “I don’t have the stress that 80 percent of New Yorkers have right this minute, worrying about their rent, their jobs.” Later, he says, “I’m not homeless, I just don’t have a place to stay right now. I don’t have a roof over my head, but I have this place to sleep.” An inescapable fact of Reay’s situation is that it has turned him into a criminal. Last year, a fifty-four-year-old man “baked to death” in a 100-degree Riker’s Island cell after being arrested for trying to sleep in a public housing project stairwell. Reay’s transgression—three years of trespassing on a private roof—could easily result in jail time if he is discovered.

His most remarkable accomplishment is to keep himself looking stylish enough to make the marginal connections and modest paychecks that support him. With Promethean effort he has managed to hold the dooming signs of destitution (the odor, the accreted grime) at bay. What may be most soul-destroying is the veneer of cheerfulness he must maintain—the “I’m doing great!” façade—that is all but obligatory to snare work on the outer margins of the fashion and entertainment worlds. Though he is isolated in his double life, he is far from alone. According to Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, the deputy mayor for health and human services, more than a third of the people in New York’s homeless shelters work full-time.

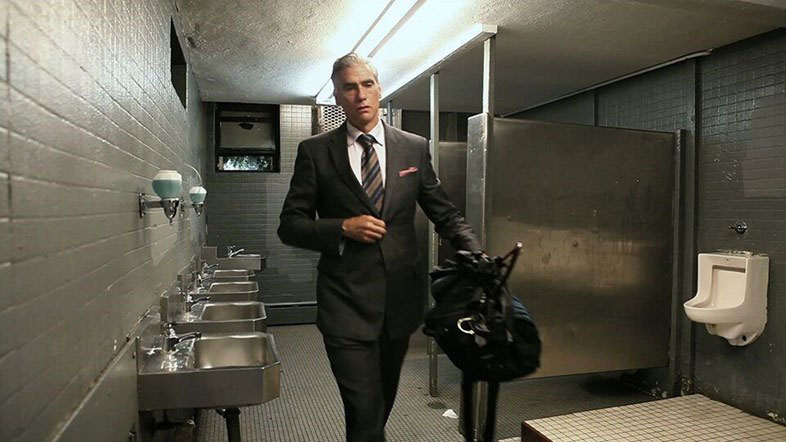

Mornings, Reay washes at the public rest room in Tompkins Square Park. But the pillar of his hygienic upkeep is a nearby YMCA where he rents three lockers, one for his photo equipment, one for shampoo and “junk,” and a third for his computer and clothes, including what appear to be more than one suit, an assortment of neckties and several dress shirts, all carefully arranged on hangers.

His other essential possession is his cell phone, through which he conducts his precarious professional life. During Fashion Week in New York, Reay provides photographs to Dazed magazine. The job involves a delirious hustle that requires him to persuade well-known models to allow him to shoot them for a pouting instant—“a street style shot”—as they flounce away from a show. He also pops up at the backstage crush at runway shows where herded photographers are as tightly controlled as at an event at the governor’s mansion. At 4:30 AM we find him at a table he has commandeered at a twenty-four-hour borscht and pirogi restaurant on 2nd Avenue, trying to cull the best images to send to the magazine. By 8 AM, he’s back at the shows.

The rest of the year Reay relies on what dribbles his way from a casting agent’s list of floating movie extras; at a moment’s notice he is available to play what he calls, with self-deprecating bitterness, a piece of “furniture” to the stars. During the course of Homme Less, he is hired to be Alien Number Sixty in the movie Men In Black III. At 5 AM, he rises from under his rooftop tarp, dons the black suit the movie wardrobe department has supplied him, and shaves with a dull disposable razor and a bottle of cold Poland Spring water in the window of a closed Duane Reade.

Later, we see him at Times Square, in the same black suit and ghostly makeup, posing for cell phone pictures with tourists—at a buck or two a shot—along with an array of other costumed cartoon and movie characters. In December, he’s a remarkably tender Santa Claus to groups of children whose faith in a jolly granter of wishes seems to nourish him at least as much as them.

Recent studies about how much income a family of four needs to make ends meet in New York vary widely—partly because the annual double-digit rise in rents in almost every part of the city makes the latest calculations outdated within months. Of the estimates I’ve seen, the median puts the amount at about $75,000. Reay, for his part, survives on about $15,000: $1,500 for his membership at the YMCA, $5,400 for food; $4,800 for going out and clothes; and $3,360 for the health insurance he has been able to obtain through the Screen Actors Guild.

On the night of his fifty-second birthday we see Reay celebrating with a small group of friends at an East Village bistro, actors and fashion industry workers who, presumably, have no knowledge of his situation. At the end of the celebration, after his friends have gone, Reay addresses the movie’s audience with a mildly sinister sneer. “One night when you’re safe and sound asleep in your beautiful bed with your Egyptian cotton covers, I’m going to sneak in and I’m going to sleep on your couch, because I’m sick and tired of sleeping on the fucking roof. You’re watching this film. You bought a ticket or someone brought you—that entitles me to sleep at your house. You may not agree, but I’m making the rules.”

He’s not threatening physical harm or theft, but simply permission to slip into our homes, like the Passover ghost Elijah, and to sleep, unmolested, before departing in the morning.

Thomas Wirthensohn’s Homme Less opens at the IFC in Manhattan on August 7.