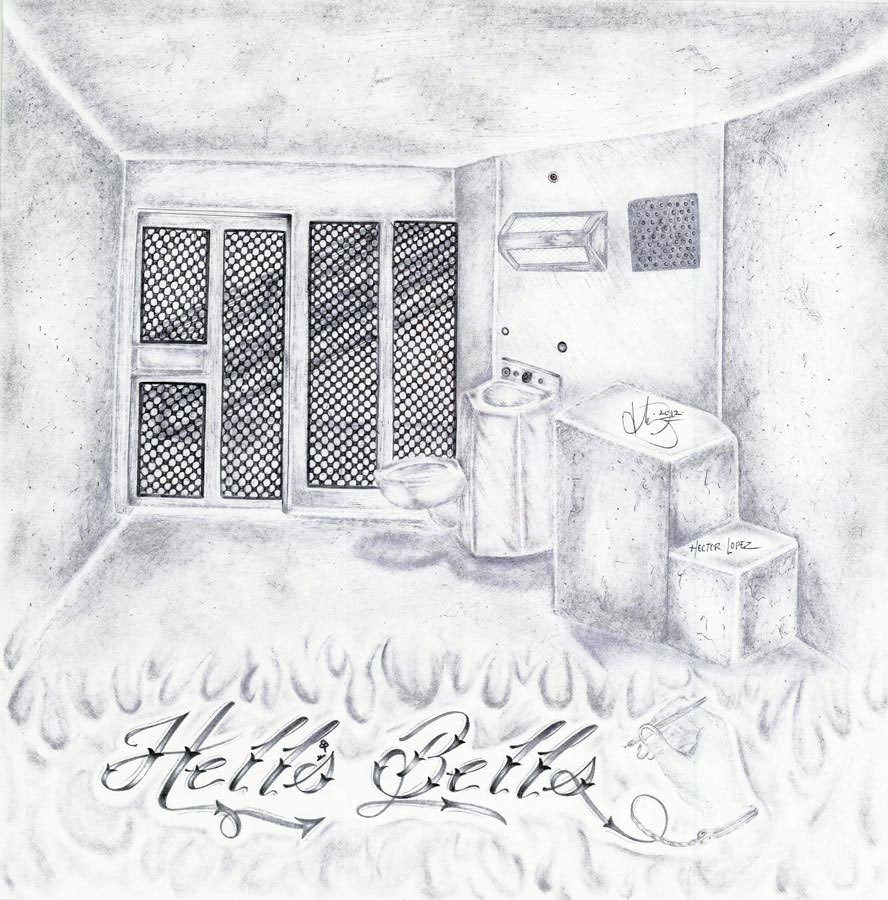

George Ruiz, a seventy-two-year-old inmate in California, has spent the last thirty-one years in solitary confinement, most of it in Pelican Bay State Prison. He has been held in a windowless cell, with virtually no human contact and no phone calls absent an emergency. He is let out for, at most, sixty to ninety minutes each day, during which periods he is kept in complete isolation. Ruiz has endured this inhuman treatment not for any prison misconduct, but solely because he is said to be affiliated with a Mexican gang. One expert who studied these conditions aptly termed them “social death.”

Since the rapid expansion of high-security prisons in the 1980s, solitary confinement has become pervasive across the United States in both state and federal prisons, involving, according to recent estimates, more than 75,000 inmates at any given time. It is imposed by prison officials for security and disciplinary reasons, but often with little oversight and on the basis of minor infractions. In California, it is often based, as in Ruiz’s case, on suspected gang ties, on the theory that gangs are the source of much prison violence. It is a preventive measure, but its preventive effects are unproven. Many other countries maintain secure prisons without resorting to prolonged solitary confinement. Now, thanks to the case of George Ruiz, along with recent criticism of the practice by Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, President Barack Obama, and prison officials themselves, America may finally be changing its ways.

In 2011, before the Center for Constitutional Rights took on a lawsuit on behalf of Ruiz and a number of other inmates, California had been holding more than five hundred prisoners in solitary confinement for more than ten years at a single facility, Pelican Bay State Prison. Seventy-eight of them had been in solitary for more than two decades. Across California, thousands of inmates were held in such isolation.

Last week, in a landmark settlement of Ruiz’s class action lawsuit, California agreed to fundamentally change its system, which is one of the most severe in the nation. Where it previously relegated prisoners to solitary confinement indefinitely for gang affiliation, it now will limit solitary confinement to defined periods of time, not to exceed five years. It will do so not on the basis of suspected status as a gang member, but only on the basis of serious prison misconduct, such as murder, violent assault, attempted escape, weapons possession, and the like, which must be adjudicated in a hearing that satisfies due process requirements.

California also agreed to release immediately into the general prison population nearly all of the inmates, like Ruiz, who had been in solitary confinement for more than ten years. And it agreed to transfer to the general prison population all those currently confined on the basis of gang affiliations, unless they have committed one of the serious infractions that is now a prerequisite to solitary confinement. In response to the lawsuit, the state has already released more than one thousand inmates from solitary, and it expects to release many more.

California’s settlement does not create a binding precedent for other states, but it does offer a model for reform. And it comes on the heels of a groundswell of criticism of America’s overreliance on solitary confinement, which is increasingly out of step with incarceration practices in nearly every other advanced country. In early May, a court in Ireland blocked the extradition to the United States of Ali Charaf Damache, wanted on charges of providing support to terrorism, citing the risk that he would face solitary confinement in the federal supermax facility in Florence, Colorado. As the Irish court found, relying on the Irish Constitution:

The institutionalisation of solitary confinement with its routine isolation from meaningful contact and communication with staff and other inmates, for a prolonged pre-determined period of at least 18 months and continuing almost certainly for many years, amounts to a breach of the constitutional requirement to protect persons from inhuman and degrading treatment and to respect the dignity of the human being.

Damache, who had been held for two years while he fought extradition, has now been released.

In June, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, who had previously criticized solitary confinement in testimony to Congress, took the highly unusual step of writing a separate opinion in a case involving another matter entirely to condemn solitary confinement and invite a constitutional challenge. He predicted that the Court “may be required to determine whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.” And since Kennedy is very often the decisive swing vote on the Court, his predictions are worth taking seriously.

Advertisement

In July, President Obama ordered the Justice Department to review the federal prisons’ use of the punishment. In a speech at the NAACP annual convention, Obama asked:

Do we really think it makes sense to lock so many people alone in tiny cells for 23 hours a day, sometimes for months or even years at a time? That is not going to make us safer. That’s not going to make us stronger. And if those individuals are ultimately released, how are they ever going to adapt? It’s not smart.

Even American prison officials themselves have begun to question the practice. Last week, one day after the California settlement was announced, the Association of State Correctional Administrators, which includes the directors of all the state prison systems and many jails in large cities, called for ending or radically limiting the use of extended solitary confinement. In doing so, they followed the lead of Colorado’s prison director, Rick Raemisch, who last year introduced major reforms in his state after voluntarily spending twenty hours in a seven-foot-by-thirteen-foot prison cell. Since then, the state has cut its solitary prison population by 50 percent.

All of this is welcome news. Depriving people of all human contact for extended, and in California’s case, often indefinite periods of time is by any modern standard inhumane. Human beings are social by nature; we are defined by our families, friends, and communities. To be deprived of any contact with other human beings is to be denied an essential element of one’s identity and humanity.

It can also “literally drive men mad,” as Justice Kennedy told Congress last year. Consider this example, cited by the Irish court, drawing on an Amnesty International report:

Quite disturbingly, they report a lawsuit on behalf of an inmate sent to the ADX who repeatedly self-harmed but after brief periods of referral to the federal medial facility for psychiatric review was returned to the Control Unit at the ADX. He variously lacerated his scrotum with a piece of plastic, bit off his finger, inserted staples into his forehead, cut his wrists and was found unconscious in his cell. After 10 years and 5 months in the Control Unit, he was placed in the General Population Unit in the ADX where he sawed through his Achilles tendon with a piece of metal. He later was placed on anti-psychotic medication following mutilation of his genitals.

In many cases, the extreme isolation seems gratuitous. Why, for example, would prisons deprive individuals in solitary confinement of the ability even to talk to another human being? Yet even phone calls to family members are strictly limited. One inmate in the California case had been permitted to speak to his mother only twice in twenty-two years. Merely attempting to communicate with other inmates—for example by yelling through thick concrete walls or vents—has been treated as a prison infraction. If deemed an attempt to converse with another putative gang member, it has been used as evidence to support continued solitary confinement as a suspected gang member.

So far, many of the reforms voluntarily adopted by prison officials involve cutting back on, not eliminating, solitary confinement. The practice has unquestionably been overused, like incarceration itself, and the easiest solutions are to end it for those who pose the least danger. But what about those who are a demonstrable threat to other members of a prison population and have repeatedly violated prison rules or endangered fellow inmates? If solitary confinement is prohibited by the Eighth Amendment and by international principles of human rights because it is cruel and inhumane, isn’t it equally cruel and inhumane when imposed on the hardened violent inmate? Here, too, the California settlement might provide a way forward. The state has agreed to modify conditions even for those who, because of serious violence and the like, require heightened security. These prisoners will be permitted more phone calls and visits with family in which they are permitted human contact. And they will be allowed to exercise in small groups when let out of their cells. Ohio adopted such an approach for its most problematic prisoners some years ago, and found that it was more effective in maintaining security, precisely because inmates had something valuable to lose.

But solitary confinement is only a small part of the challenge. Its roots lie in America’s unduly harsh approach to criminal justice. And from those roots grow a multitude of problems: police forces that too often resort to violence because they have forfeited legitimacy in the communities they serve; mandatory minimum and “three strike” life sentences for drug and other felony offenses that warehouse people for far too long; mass imprisonment, which makes us the world leader in locking up human beings; and the death penalty, a sanction every other Western country has long abandoned as barbaric. Even without solitary confinement, conditions for many jail and prison inmates are extraordinarily and unnecessarily severe; most of the general population in California’s prisons are locked down in their cells for twenty-two hours a day. What’s needed is a sea change, not an isolated fix.

Advertisement