Standing underneath the golden dome of the shrine of Imam Husayn ibn Ali in Karbala, Iraq, in mid-September, I couldn’t help wondering what would happen if it were hit by a rocket, or damaged in an explosion. Even imagining such horrors seems wrong, and yet the particular history of this remarkable Shia pilgrimage site, and the current situation of Iraq, makes it difficult to avoid. In fact, I stood in this very place almost twenty-five years ago, examining the destruction wrought by just such an attack—in that instance, mortar fire by forces of Saddam Hussein as they wrested control of the complex from Shia insurgents holed up inside following their failed uprising. The regime re-established control—in Karbala and most of the country—and over the years allowed the shrine, which houses the burial chamber of the seventh-century Shia martyr, to be repaired. After 2003, the Shia religious establishment carried out major renovations, producing the magnificent sanctuary that now graces the site.

Today, the shrine is more likely to be a target for the Islamic State. Ever since 2006, when ISIS’s progenitor, al-Qaeda in Iraq, blew up the golden dome of the Shia Askariya shrine in Samarra, further north, unleashing the darkest phase of Iraq’s civil war, the extremist group has made a sectarian battle against Shias a central part of its ideology. And over the past sixteen months, as ISIS has taken control of substantial Iraqi territory, it has sought to wipe out any vestiges of Shia or other “deviant” traditions that it finds. Since many of the most important Shia shrines are in Iraq—in Samarra, Karbala, Najaf, and Baghdad—a single such attack could start an all-out conflagration.

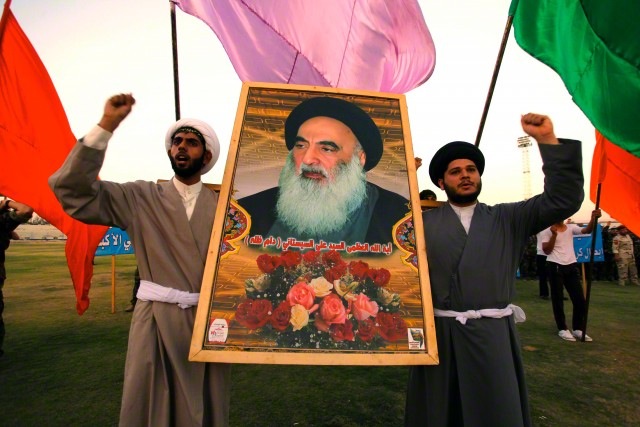

Yet at the Imam Husayn shrine, as at other monuments I visited, security is fairly light. In fact, in contrast to my previous visit in March, the fight against Daesh, as ISIS is known here, does not appear to be paramount in Iraqis’ minds. One explanation for this seems to be that, while the defeat of ISIS may not be imminent, Iraq’s Shias and Kurds have been reassured by the knowledge that neither Iran nor the US is likely to allow Baghdad or Erbil, the Kurdish capital, to fall to the group. But there is another explanation as well. With the government of Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi floundering and the Iraqi army in disarray, the country’s Shia religious leadership has reasserted itself as the Iraqi state’s guardians, providing moral and, increasingly, political guidance. Collectively known as the Marja’iya, and based in the holy city of Najaf, one hundred miles south of the capital, the Shia establishment is led by four grand ayatollahs, who jointly command the passionate support of much of the Shia world; the Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani is generally acknowledged to be the first among equals (with a religious stature that exceeds that of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei).

In June 2014, in response to ISIS’s blitz-like conquest of Mosul and Tikrit, Sistani issued a general call-up to the Shia masses to step in and defend the country. With Iraq’s high unemployment and rapidly growing youth population—the median age is just 21—many young people were ready to serve. And yet it is far from clear whether the resulting series of militias, controlled by different interests with different aims, will be up to the task of taking on the Islamic State and maintaining the country’s security. Among other things, the ayatollahs are not military commanders, which has meant that Sistani’s appeal has encouraged Shia militias backed and even directed by Iran to take the lead in fighting ISIS.

At present, ISIS controls parts of four majority-Sunni provinces with an estimated population of some 6 million, or about 20 percent of Iraq’s total population, and continues to push forward along a line stretching from the Syrian border in the north down to the capital and west toward the Jordanian and Saudi borders, not far from Karbala. But in the large swathes of the country not under its control or on the front lines there is a deceptive sense of calm. Stores are overflowing with middle-class consumer goods and electronics, markets are bustling, and in towns like Najaf new hotels are opening, not just for the many visiting pilgrims but for businessmen from Iraq, Iran, and the Gulf. One can travel, as my colleague Maria Fantappie and I did in September, throughout much of these areas without major security concerns (though a recent rash of abductions in Baghdad—targeting wealthy Iraqis and Turkish workers—suggests that keeping a low profile is advised).

Underneath the surface, however, tensions are high. In the Kurdish region, the two main political parties have been publicly tangling over the succession of longtime president Masoud Barzani, whose term (already extended once by political agreement two years ago) expired on August 19, but who continues to hold office. Meanwhile, a series of financial crises—provoked by collapsing oil prices, the cost of fighting ISIS, a growing flow of refugees and internally displaced people, and the breakdown of a budget-sharing agreement with Baghdad—have plunged the region into recession. Ordinary citizens are seething about the delayed payment of public-sector salaries, now months behind schedule, and the Peshmerga, Kurdistan’s once vaunted security forces, have lost some of their luster following the encroachments of ISIS.

Advertisement

In Baghdad and the south, where Shia form a substantial majority and are in control, popular protests in early August over power cuts and, more generally, endemic corruption and deeply deficient services by state agencies, have forced Prime Minister al-Abadi to announce a hasty set of reforms. Following ISIS’s rapid conquest of Mosul and other parts of the country in June 2014, al-Abadi was chosen by his Da’wa party to head the government, replacing his Da’wa predecessor, Nouri al-Maliki, who was blamed for the defeat. But lacking strong backing from other parties, al-Abadi remains a weak leader who has struggled to make substantive changes; following the protests, he eliminated several ministries overnight, as well as the positions of deputy prime minister and vice president (each held by three persons), and launched a public-sector salary review. A more thorough reform effort would require him to forge political alliances in parliament that could push through overdue legislation, but he alienated many parliamentarians by reducing each member’s stable of bodyguards from thirty to eight as a cost-saving measure, so progress remains in doubt.

If al-Abadi responded with an uncommon sense of urgency to street demonstrations, it was not because he feared an “Arab Spring” type of movement that would undo the order over which he presides. Iraq has had regular elections, and the current government is just over a year old; it may not be very effective, but it has a degree of legitimacy and support. His main concern, rather, has been that his political rivals, backed by militia power, might exploit popular ferment at his expense, and possibly seize control.

This fear is not unjustified: the Iraqi army is in shambles, with only a handful of effective fighting units, as well as a US-trained counter-terrorism force, left from its disastrous collapse in 2014. The real centers of power in Iraq now lie elsewhere, above all with the religious leadership in Najaf and with Iran’s own proxies in the country. Since the Grand Ayatollah Sistani’s June 2014 call for a hashd al-shaabi, or “popular mobilization,” against ISIS, an amalgam of hashd, or armed militias, have emerged, which are primarily responsible for the fight against ISIS. Those volunteering to join report to the army base or police station or political party headquarters in the areas where they live (throughout Baghdad and the south), and are then sent up to the front for specific battles against ISIS.

But the hashd themselves are divided; while some follow Sistani and are grouped under the army, others have a quite different organization and aims and cannot be relied on to back al-Abadi. The former, known as the “Hashd Sistani,” are a largely unorganized group of young men, called “volunteers” rather than hashd by the Marja’iya. Most have minimal training, are not accustomed to battle, and moreover have little motivation to liberate Sunni areas; many have been killed. Two other kinds of hashd, meanwhile, are under more or less direct Iranian influence: those popularly known as the “Hashd Soleimani” are a well-trained set of militias, equipped and supervised by Iran’s Qods Force under its commander Qasem Soleimani, an Iran-Iraq war hero who has pranced along the frontlines in the battle against ISIS (and portrayed himself as the country’s redeemer); and the so-called “Third-Term Hashd” (hashd wilayet al-thalitha) are supporters of Abadi’s predecessor as prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, who is said to be making a bid for a return to office based on his newfound militia power and an undying ambition. (Iran’s Qods Force is not backing Maliki in particular: it is supporting anyone who wants Iran’s backing and can somehow be trusted to do its bidding.)

This diverse mix of fighters and commanders can make for a bewildering spectacle at major battles, with multiple lines of command and conflicting strategies, as was the case in Tikrit in April. The disorganization augurs poorly for future offensives against the Islamic State, such as for the strategic town (and oil refinery) of Baiji, situated midway between Baghdad and Mosul, control of which has passed back and forth over the past year; and Ramadi, west of Baghdad, which fell to ISIS in May 2015. The greatest prize, the city of Mosul—Iraq’s second largest city and the largest city under ISIS control—seems out of reach for now, with its reconquest repeatedly postponed for lack of forces capable of the job.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Iran has become increasingly bold about asserting its influence. This clearly was not what the Marja’iya had intended: to establish armed groups to defend the homeland against an acute threat such as ISIS is one thing, but to surrender them to the designs of Iraq’s powerful neighbor, which seeks to ensure a friendly, Shia-controlled Iraqi state under its close tutelage, quite another. Rumors have flown in recent weeks about Iraqi frustration with Iranian interference. Sistani is said to have written a letter to Khamenei, excoriating Qods commander Qasem Soleimani for conducting himself inappropriately—acting not as the foreign guest he is but as Iraq’s de facto military chief of staff; while Prime Minister Abadi is said to have evicted Soleimani from a National Security Council meeting and to have ordered an inspection of the plane carrying him from Tehran.

Ever since the removal of the Hussein regime in 2003, Sistani and his followers have backed a constitutional order based on inclusive politics (which they may have thought the best guarantee for the survival of Shia dominance in Iraq’s ethnic, religious, and political mosaic). They saw the emergence of armed groups following the dismantlement of the Iraqi army, and the ensuing sectarian war between Shia militias and Sunni insurgents, as a threat to Iraq’s long-term stability. The US “surge” against al-Qaeda in Iraq in 2007, along with the Sunni awakening and former prime minister Maliki’s readiness to stand up to the Shia militias, helped put the demon back into its box.

Following the US troop withdrawal at the end of 2011, the Iranians assumed they would be able to wield direct influence over Baghdad’s Shia-led government and militia power did not seem to be as important. And in the early years of the war in Syria, Iraqi and Iranian interests seemed to coincide: many Iraqi Shia fighters flocked to Syria, ostensibly to protect the Sayeda Zeinab Mosque, a prominent Shia shrine in the southern suburbs of Damascus, but in practice defending the Iranian-backed Assad regime. But former prime minister Maliki’s alienation of the Sunni population and renewed willingness to condone Shia paramilitary groups, followed by the arrival of ISIS, dramatically changed this situation. Few Iraqis are any longer concerned about fighting in Syria; the battle is now at home. And with Sistani’s call for a popular mobilization, Iran has exploited the opportunity to use militias to guide the Iraqi offensive as much as it can.

Partly as a result, Sistani’s ability to influence the direction of the country is tenuous. Since the 2003 US-led invasion, the Marja’iya has had a prominent part in national politics, providing moral and political guidance to the leading politicians at crucial junctures. In 2003, for example, Sistani insisted that a new constitution be drafted by popularly elected, rather than US-appointed, Iraqis; he thereby secured the Shias’ accession to power. His subsequent call on Shia not to respond to the extreme provocations by al-Qaeda, whose bombings targeted them in their markets and mosques, was largely heeded until the explosion at Samarra in 2006 provoked a terrifying cycle of reciprocal vengeance. But the grand ayatollah has been reluctant to wield direct political power along the lines of the Iranian system of velayet-e faqih, or governance by clerics.

To close observers, Sistani’s appeal against ISIS was no surprise, but all the same suggested a new assertion of power by the Marja’iya. And in view of the country’s very weak political institutions and failing military, this expanded involvement in national security has been embraced by many Iraqis. Indeed, though there is widespread resentment of Persian interference in Iraq, some are looking eastward with envy, seeing a nuclear-powered, stable, and ascendant Iran that expects to be readmitted into the community of nations, while their own country is an utter mess. Perhaps there is something to be said for this velayet-e faqih? Some members of Iraq’s Shia elite are saying the Iranian approach may provide the answer for the country’s ills, and criticize Sistani for being insufficiently forceful in his interventions.

This doesn’t appear to be the Marja’iya’s inclination. As an ayatollah’s aide in Karbala told us, Iraq’s stability is a paramount concern for Sistani: he could not allow Maliki, as prime minister, to turn Iraq into Iran’s backyard and into a battleground between Tehran and Washington, or to give ISIS free passage. He is said to be fed up in particular with Iraq’s post-2003 generation of religion-based parties, which are thoroughly corrupt, though they invoke his name, and God’s, at every turn to gain legitimacy.

Sistani also supports thorough reforms, especially to curb government corruption. Yet there is a tacit acknowledgment in religious circles that the clerics’ political influence has limits. “Iraqi people want religion to rule and at the same don’t want that, so they end up accepting it only temporarily: in order to secure a situation in which they can freely practice their religion,” one cleric suggested. (As I discovered, Iraq’s Shia clergy may decry the direct involvement of religion in politics but they relish talking politics with a visitor—in detail and at length.)

What both the ISIS and governance crises have laid bare is the bankruptcy of the post-2003 political class, which has mismanaged and ruined the country they inherited from a US military power that itself was utterly incapable of managing it. While rightly decrying the Saddam Hussein regime for its appalling oppression, these parties—including Abadi’s and Maliki’s Da’wa, the Badr Organization, and the Supreme Islamic Council of Iraq, to name only the largest—have increasingly mimicked the Baath party’s structure and methods. They’re secretive, suspicious, and undemocratic, and if their rule has not been as systematically repressive as their predecessor’s, it is only because they have failed to consolidate power in the same way. They operate, moreover, in a society that openly scorns their rule yet assents to it for lack of a better alternative. The tragedy of post-2003 Iraq is that its population, whether Shias, Sunnis in Daesh-controlled areas, or Kurds under Barzani, continue to rely on the same repressive modes of government.

This may account for the fact that little distinguishes the parties other than the colorful personalities running them. The only significant difference that has emerged recently concerns Iran’s more direct and visible presence since the arrival of ISIS. The Shia community has become split over whether to maintain a balance between Iran and the United States, two powers that have shared interests in Iraq, or to use Iran’s rising clout to push back ISIS and secure their own hold on power. The Marja’iya believes in balancing; it is joined by Prime Minister al-Abadi (whose fate now hangs on the success of his reform effort and Sistani’s continued support) and several Shia parties.

How this balancing can occur when Prime Minister al-Abadi’s own Da’wa party has a faction led by Maliki and backed by Iran that is trying to unseat him is unclear. A Da’wa official in Karbala was quick to come to Maliki’s defense, insisting that Da’wa is genuinely Iraqi and that relations with Iran are based solely on commonality of religious belief; that while many Iraqis seem to think that Maliki went over to the Iranian side in opposition to the US while serving as prime minister, he was in fact performing a balancing act; and that Saudi Arabia encouraged the perception of him as an Iranian proxy and shut him out, thereby pushing him into Tehran’s corner by default. Most important, according to this official, was that Da’wa does not subscribe to velayet-e faqih: “That’s an Iranian concept. Here we believe in the wilayat al-umma ‘ala nafsihi,” the notion that human beings should manage their own affairs. Whether the statement is true or not is an open question. But these days, it sounds almost revolutionary.