Among the dozen useful masterpieces chosen by the US Postal Service for its 2011 series of stamps honoring American industrial design pioneers is the Normandie water pitcher (1935), a sleek chromium-plated vessel whose prow-like form echoes that of the then-new French ocean liner for which it was named. This stunning work, manufactured by the Revere Copper and Brass company, evokes the glamour of interwar transatlantic travel with a sculptural purity worthy of Brancusi, and is rightly included in numerous design history books and museum collections. Yet until now the general public has known next to nothing about its creator, Peter Muller-Munk.

That lapse is finally redressed by “Silver to Steel: The Modern Designs of Peter Muller-Munk,” an illuminating exhibition at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art. It vindicates the personal crusade of the Miami-based design historian Jewel Stern, an intrepid researcher of this overlooked figure and the co-curator of the show.

Stern is particularly interested in the transmission of modern design ideas from Europe to the United States, which in previous books she has revealed to be a far more complex and dispersed process than had been thought. Her diligence has paid off handsomely in this fascinating survey, and confirms the unjustly neglected Muller-Munk’s rightful place in the top tier with his much better known American contemporaries Donald Deskey, Henry Dreyfuss, Norman Bel Geddes, Raymond Loewy, and Walter Dorwin Teague.

Co-curated by Stern and the Carnegie’s Rachel Delphia (who together with Catherine Walworth wrote the informative catalog), “Silver to Steel” gathers some 125 pieces spanning Muller-Munk’s four-decade career. It traces his evolution from craftsman of precious objects to stylist of household appliances like refrigerators and vacuum cleaners, part of a broader midcentury shift in innovative American design from high-end exclusivity to mass-market practicality.

Klaus-Peter Wilhelm Müller was born in Berlin in 1904, the son of upper-middle-class Taufjuden (baptized Jews) who converted to Protestantism. (He appended his mother’s maiden name, Munk, to the more commonplace Müller, and when he came to America dropped the umlaut.) Raised in a cultivated milieu, he nonetheless yearned to “do something with my hands,” and was apprenticed to the accomplished Berlin sculptor and silversmith Waldemar Raemisch. The eager student showed extraordinary aptitude for metalwork, and in 1926 immigrated to the economically booming United States.

Confidently presenting himself at Tiffany & Co. in New York, Muller-Munk was hired for the firm’s silver workshop on the spot, but grew bored with routine tasks and quit within a year. His father’s backing allowed him to open an atelier in Greenwich Village, where he designed and executed hand-wrought silver bowls, boxes, coffee services, and the like. The New York Times praised them as “highly individual and, while modern, not extreme or…bizarre,” while The New Yorker mentioned him in the same breath with the renowned Georg Jensen (nearly four decades his senior) as “two silversmiths worth remembering.”

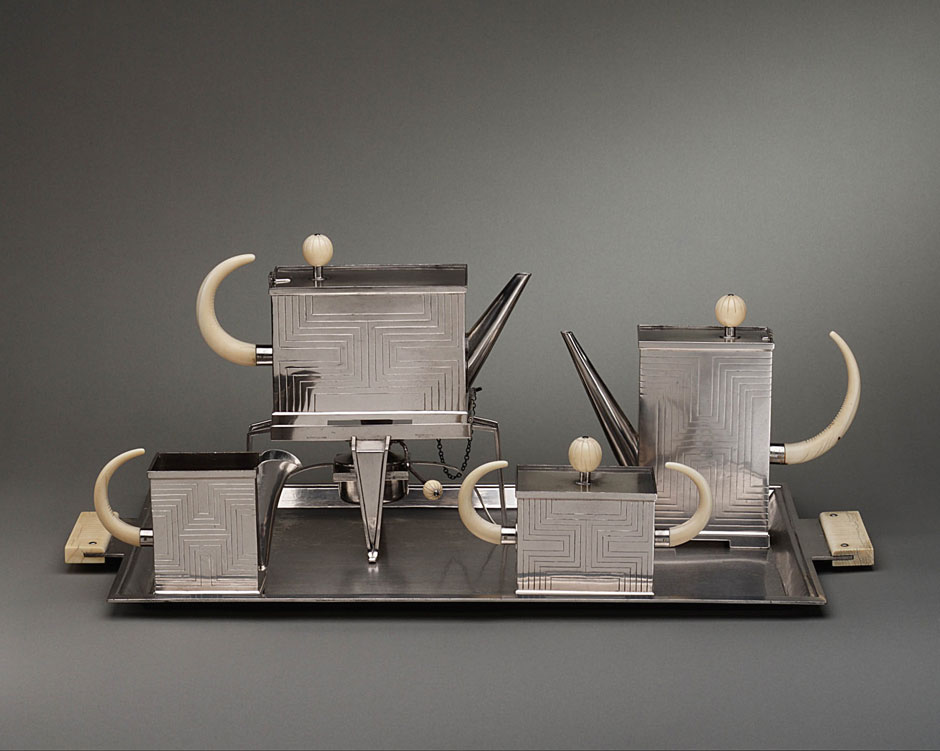

Muller-Munk was always attuned to the latest trends in European metalwork. Stern tactfully notes the “uncanny resemblance” between his dramatic 1929 silver candelabra—with pairs of arms that flow upward and outward like Art Deco cascades—and the German architect Dominikus Böhm’s very similar and prominently published wall lamp of two years earlier. But Muller-Munk was never predictable, and moved with ease from a round, fluted silver bowl (circa 1928) akin to Josef Hoffmann’s designs for the Wiener Werkstätte, to graceful leaf-like shapes for a footed silver centerpiece (1929-1930) to a severely squared-off silver-plated tea service with tusk-like ivory handles (1931).

As the Great Depression deepened, he turned from exquisite luxury items to the emergent field of industrial design, which exploited up-to-date styling to make domestic appliances—necessary purchases in bad times no less than good—look efficient and desirable. A year after he married in 1934, Muller-Munk moved to Pittsburgh, where he joined the new industrial design faculty of the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) and sought manufacturing clients for his own projects. He convinced school officials this was no conflict of interest but rather a necessary application of his didactic role.

Several of his designs—including chic cigarette lighters and a streamlined digital clock—reached the marketplace before the US entered World War II. But none became as ubiquitous as the Waring Blendor (1937), a food and drink mixer that tapped into the post-Prohibition craze for frothy mixed cocktails and ice cream sodas, as well as sauces found in fancy cookbooks. (The spelling of “blender” was altered to signify its proprietary status, and the gadget was named for Fred Waring, a popular choral-group leader who invested in its development and promoted it relentlessly.)

Advertisement

The original inventor’s prototype worked imperfectly, but Muller-Munk transformed the device into a marketable product. Its streamlined, circular chromium-plated base with four skyscraper-like setbacks and slightly flared transparent glass cylinder recalled a Moderne light fixture. This precursor of today’s Cuisinart became a huge success, and, built to last, it can still be found in many American kitchens.

When peace came in 1945 he resigned his teaching post and founded Peter Muller-Munk Associates, whereupon his design career soared. The office’s extensive client list included Bell & Howell (home movie cameras and projectors), Bissell (carpet sweepers), Silex (steam irons and coffee makers), and Westinghouse (refrigerators and radios).

Just as Depression-era manufacturers used streamlining to imply that their goods were cutting-edge developments (when the inner workings were often no different from earlier models), postwar companies employed an ever-changing array of colors to set their new models apart from the metallic finishes typical of 1930s and 1940s appliances. Muller-Munk’s “frosty blue” gas range for Caloric (1955), jewel-tone Lady Schick electric shavers (1958), and Griswold turquoise or tangerine porcelain-enameled steel cookware (1962) all catered to the notion that household devices should be not merely functional but fashionable as well.

However, because Muller-Munk’s late-career efforts centered so strongly on appliances, his reputation fell victim to the same planned obsolescence that motivated his clients. The electrically operated machines he designed had limited lifespans, were superseded by newer models, and then discarded. The color wheel whirled around too, as the powder pink and mint green of the 1950s gave way to harvest gold and avocado at the end of the following decade.

In contrast, low-tech objects may go out of fashion, but they remain useful even if consigned to the attic. Thus, unlike Russel Wright’s ceramic dinnerware or Charles and Ray Eames’s molded plywood furniture, which survived changing tastes and are now avidly sought, there are comparatively few Muller-Munk objects available to collectors. (A rare postwar exception is his 1956 Tricorne line of angular-shaped crystal table accessories for the Belgian glassmaking concern Val Saint Lambert.)

Another factor in Muller-Munk’s posthumous eclipse was his early death at age sixty-two. His wife, who had long been in poor heath, committed suicide in 1967 and he, distraught, took his own life one month afterward. Stern’s touching account of this double tragedy—which displays the author’s human sympathies as much as her research skills—observes that friends of the couple “recalled the Muller-Munks saying that when one of them died the other would too.”

His last major commission was the symbolic centerpiece of the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair—the Unisphere—a twelve-story-high, openwork stainless steel terrestrial globe that remains on its original site in Queens’s Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. It seems most ironic that the designer of such an enduring landmark of the New York cityscape, which is visible to millions of visitors to each year as they head into Manhattan from JFK airport, was forgotten for a half century after his death.

The Unisphere depicts the Earth’s continents in topographically layered high relief, with longitude and latitude lines that act as a peripheral armature, surrounded by three halo-like orbital satellite rings that acknowledge the then-recent advent of the Space Age. Despite its 700,000-pound weight, what might have been a gravity-bound behemoth conveys an unexpected buoyancy, even jauntiness, thanks to its apparently delicate perch atop an inverted tripod and accurate replication of the earth’s 23.45-degree tilt from a perpendicular axis. When the ninety-six-jet fountain encircling its base (happily restored in 2010) spritzes upward, the cumulative effect is one of alchemical lightness, the uplifting quality that Peter Muller-Munk brought to his malleable and memorable metalwork.

“Silver to Steel: The Modern Designs of Peter Muller-Munk” is on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art through April 11, 2016. The catalog, by Rachel Delphia, Jewel Stern and Catherine Walworth, is published by Prestel.