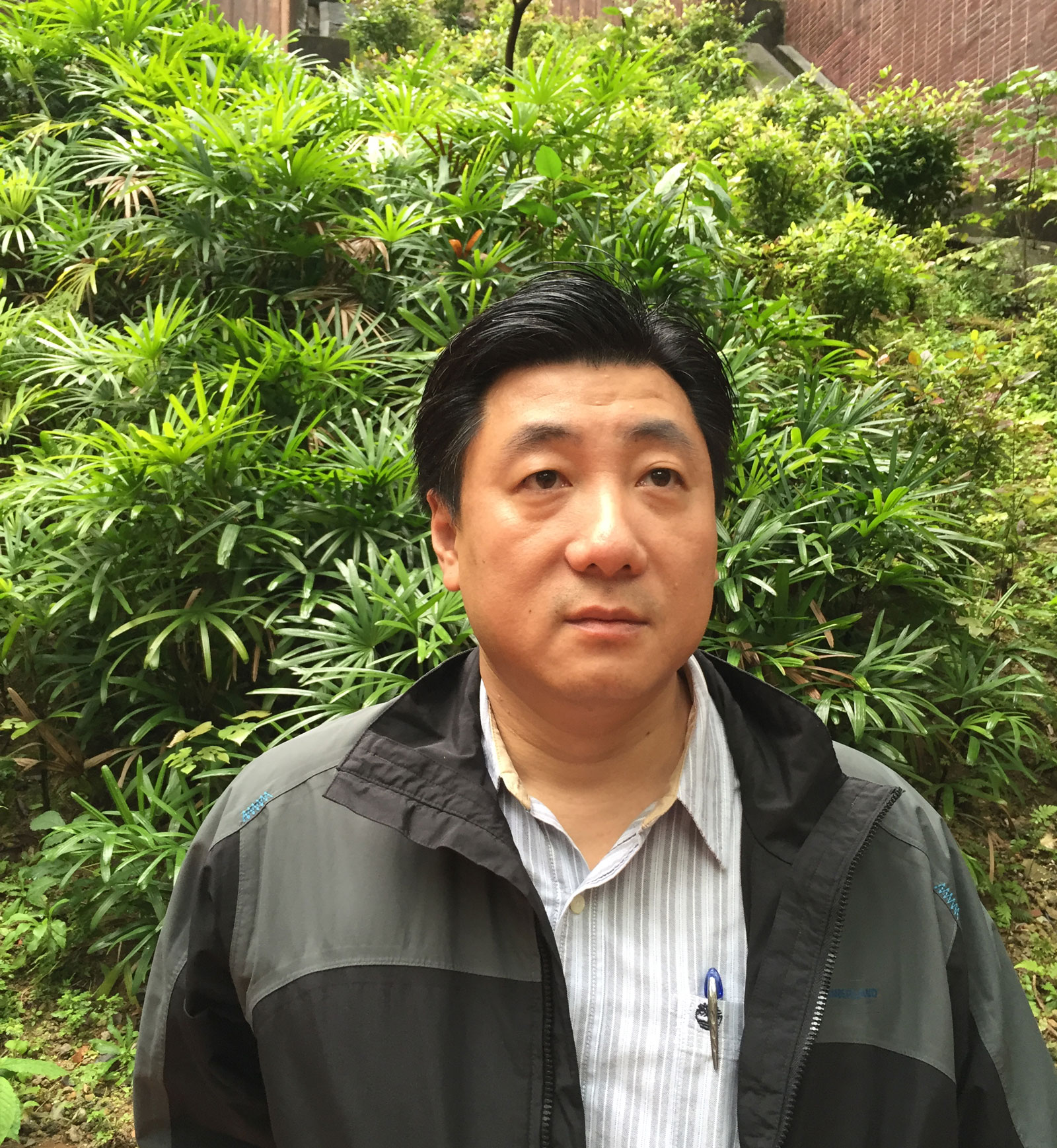

The presumed kidnapping of the Hong Kong bookseller and British citizen Lee Bo late last year has brought international attention to the challenges faced by the Hong Kong publishing business. During a break from The New York Review’s conference on the “Governance of China,” which took place in Hong Kong earlier this month, just weeks after Lee’s disappearance, I spoke to Bao Pu, one of the Chinese-language world’s best-known publishers of books about the Chinese government.

Along with his wife, Renee Chiang, the forty-nine-year-old Bao runs New Century Press, a small but highly influential house that specializes in works about Chinese politics that would be banned on the mainland. The son of Bao Tong, the well-known policy secretary to deposed Communist Party chief Zhao Ziyang, the younger Mr. Bao participated in the 1989 Tiananmen protests, and then moved to the United States where he became a citizen and worked as a consultant. In 2001, he moved to Hong Kong, working first at a high-tech start-up. In 2005, he and his wife founded New Century.

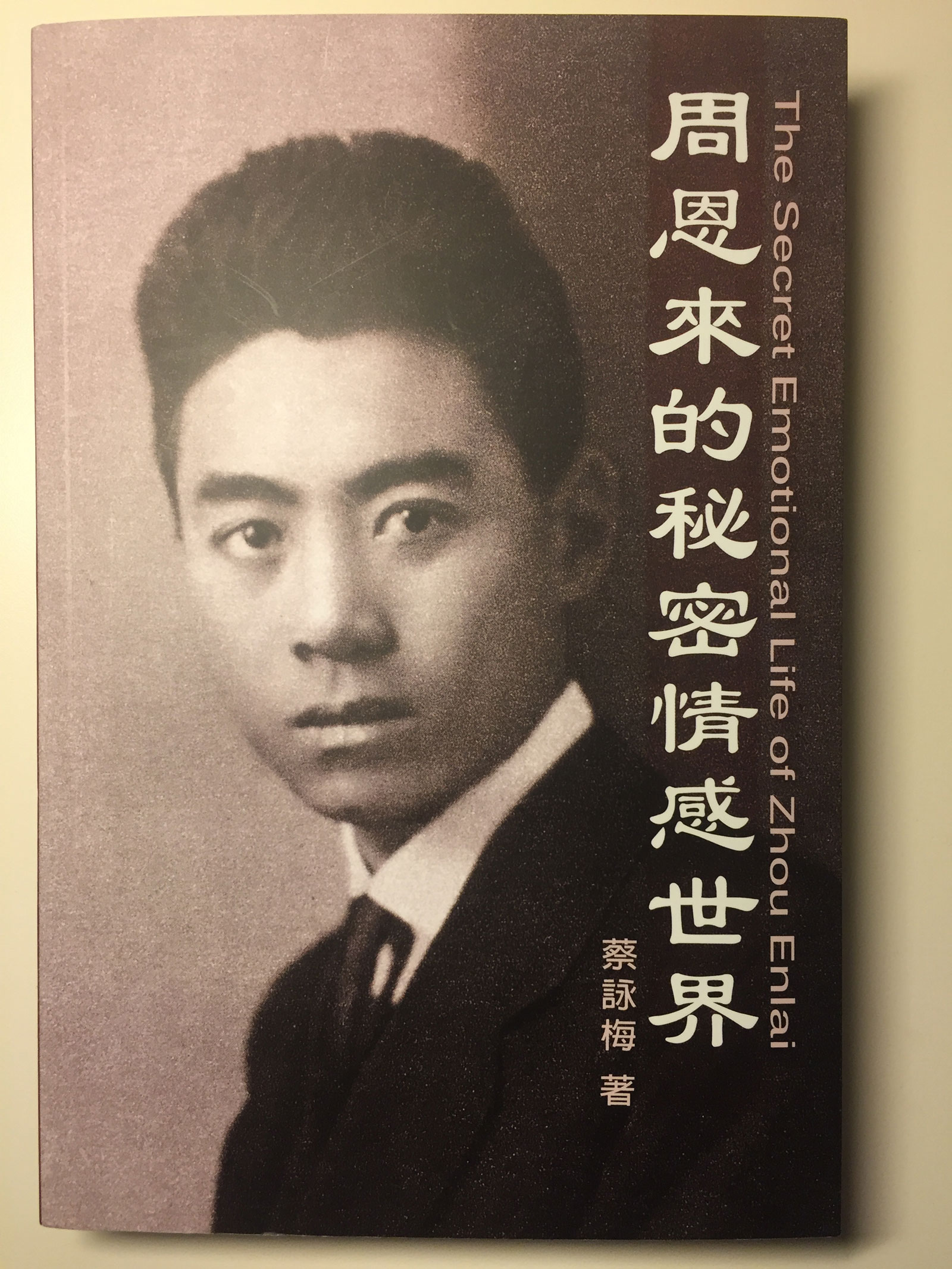

The books Bao publishes tap into a vein of political writing that challenges orthodox interpretations of Chinese Communist history; they include the secret journal of Zhao Ziyang (translated as Prisoner of the State), and Xu Yong’s photos of the 1989 Tiananmen protests. Its most recent book draws on close readings of Zhou’s diaries and papers to argue that Communist China’s most famous premier, Zhou Enlai, was gay.

Ian Johnson: The books you publish are often critical of the government, or highlight forgotten parts of history that the government wants covered up. Why do you bother if you’re so pessimistic?

Bao Pu: I just do what I can. That’s the current value that I hold. I have no ambition to save China.

One of your first big coups was publishing Zhao Ziyang’s secret memoirs in 2005. How did you do it?

I had been brokering manuscripts by Party cadres who had been victims of the system. I was negotiating with the old Communist Party cadres who had Zhao Ziyang’s recordings. It was a complicated process to convince the cadres to agree to do this. They had the tapes. They wanted to know who would publish. So eventually I said I would. They said, Do you know how to do publishing? So I published a few books to prove that we could. That’s how we did it. We did poetry books and intellectual books. It was all professionally done—just to convince them.

And then after you published the secret journals, a lot of people got in touch with you. You published analyses of political reform in the 1980s, a biography of the reformer Chen Yizi, and memoirs of reform-minded generals, such as Qiu Huizuo, and Ding Sheng.

In the mainland many former officials or their families had grievances against the Party, so I thought maybe it’s time to preserve it.

Publishing these kinds of books seems increasingly sensitive with the recent kidnappings of employees of a Hong Kong publisher. Are you worried you’ll be next?

They’re in a different business. They’re selling a product, and whatever sells they’ll sell. I was irritated by the media because they kept grouping all independent publishers together in one “banned books” category. But booksellers just publish whatever they want [without regard to facts]. Truth and fabrication are different.

How do you make sure your books are accurate?

Most importantly, I insist that authors of non-fiction use their real names; no pen names. Even though there is risk, they must be willing to take the risk and responsibility for their writing. I find people who know the subject in question to edit and fact-check. I have a Cultural Revolution guy. A guy who does early Mao. Others.

And the books are printed in Hong Kong. Have any been shipped to the mainland?

That’s difficult to do. People buy them in Hong Kong and carry to the mainland, but this has become tougher recently because of stronger border controls. This has hurt our sales.

You’ve been publishing fewer books in recent years. Last year, you published only three books. Why have you scaled back?

The main problem is the new generation doesn’t want to know. They don’t know about the Mao era or who Deng was. Another big problem is there aren’t interesting manuscripts.

Why?

The hongerdai [the “second red generation”—the children of the founding generation of Communist leaders] are liberated under Xi Jinping. In the past they had grievances, but now they feel that this is the best time for their interests: “We don’t want to rock the boat.”

What about memoirs of the Cultural Revolution? I don’t mean famous people but common people, what they experienced in those times, when millions were killed, sent into exile, beaten, and tortured.

Advertisement

Unfortunately they’re not very interesting. Everyone feels he was a victim. If you look at them, you wonder, What the fuck were you doing in that situation? It was everyone else’s fault? You can’t blame everything on Mao. He was responsible, he was the mastermind, but in order to reach that level of social destruction—an entire generation has to reflect. But they all say they were victims.

I had this manuscript by Cheng Weigao [the former Party Secretary of Hebei Province toppled by charges of corruption in 2003]. He said, “I thought about this after I was put in jail: our system lacks rule of law.” I thought: Where the fuck have you been? When you were taking advantage of the system you didn’t care about this. Those corruption charges involved profiteering on real estate projects, and those always involve chasing people off their land [forced evictions, often violently]. But he didn’t discuss that.

What are some of the projects you are interested in now?

I am interested in telling stories about human nature. The Communists are so against human nature. The world needs to know more about Chinese culture. But there’s no creativity in the mainland. I mean, books like Wolf Totem? Give me a break. Censorship has stifled creativity.

Then you’ll be doing soft power for China.

I’m going to demythify Chinese culture. My example is Alan Moore’s graphic novel V for Vendetta. A lot of Orwell’s ideas are apparently too complicated for today’s young people, but V for Vendetta is instantly understandable. Our next book will be like that—a graphic non-fiction book on the Lin Biao incident [the probable attempted coup and flight by Mao’s most trusted aide in 1971, ending in his death in a plane crash].

It’ll be censored on the mainland.

I want to ignore the censorship. It will sell to overseas Chinese but the people on the mainland, they’ll get it. If they like it, they’ll get it. The Zhao Ziyang book had 20 million downloads.

You studied at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Should Princeton remove Wilson’s name from the school?

I feel uneasy. Morals are unreliable in history. I’m a believer in Max Weber in that sense. He has a profound statement that no one takes seriously, which is that the direction of human society is progressively toward disenchantment. You keep breaking the beliefs that you had before. You had more convictions in ancient times but now things are breaking up and you have different ideas.

But there has to be some minimal morality.

Currently, yes, but in a hundred years it might shift.

Should we judge Mao?

There’s no justice in history. It’s kind of scary.

It’s depressing.

There is no ultimate meaning either.

So what motivates you, then, to publish these books?

I just view it as my personal vendetta. I was on the street [in Tiananmen Square] and people started shooting. I don’t believe they should have shot at me. The [official verdict on the] June 4 event as a “counterrevolutionary movement” has to be overturned.

But you still seem idealistic. You worked at Human Rights Watch. You compiled databases of dissidents. You say you just want revenge, but I don’t believe you. Is it really all a vendetta?

[Laughing] Even my wife doesn’t believe me. But I cannot give it a higher meaning. It’s how I see it. I thought that anyone who saw what I saw, would feel what I feel.

But that’s a sense of justice.

Even a monkey has this feeling. There’s a famous experiment with monkeys and grapes. They sense injustice too.

So you have a monkey’s sense of justice?

That’s our nature. It’s not much higher. We like to think we’re higher beings but we’re not.

Your father, who was one of the senior aides to Zhao Ziyang, was jailed for his role in promoting political reform and has been under continual surveillance for twenty years. Is this about avenging him?

It’s not about him. When I consider his career, he did what he could. But he’s still got a problem. That he sacrificed himself for some greater good—I reject that. After 1989 his role has been to engage in a permanent political struggle. He feels he’s still part of it. I feel he should step back and reflect, rather than still try to participate. I’ve told him that many times. For him, no, it’s an ongoing political struggle. He says he’s got a struggle that’s bigger than his life. That’s the trouble with these old Communists.

Advertisement

Aren’t you like that? You’ve got your struggle and he has his.

I reject his generation’s grand project to save China or to build the ideal society. Their value is that, “My life isn’t important compared to this grand project for the betterment of humanity.” That sounds very good. But if you believe in that and if you’re in power, chances are you’ll sacrifice other people without blinking an eye. Just a half step from that ideal situation, you have a mass murderer.

All these people, including the victims of the revolution, like the deposed defense minister Peng Dehuai, the deposed former president Liu Shaoqi, and even Zhou Enlai, are the same in this way. It’s dangerous. So that’s why I say that for me it’s a personal vendetta. I’ve thought this through. For my internal logic it makes sense. I’m not going to sacrifice myself for a grand idea. That is not the way to go.

Part of Ian Johnson’s continuing NYR Daily series, “Talking About China.”