The infatuation of early twentieth-century Russian avant-garde artists with the Bolshevik regime is a well-known story. Like many romances of unequally matched partners, it ended badly. On one side, there was a fantastically talented, motley assortment of artists unattached to the upper echelons of pre-revolutionary art patronage and power; on the other was a revolutionary party that, to the surprise of many, seized power in a vast country. Concurrently, technical advances were making photography and film—relatively new mediums—ever more accessible and easier to produce. As Lenin famously noted, “cinema was the most important of the arts,” but both were of vital importance to a regime that needed to communicate with a largely illiterate population. The serendipitous confluence of technology, art, and politics in these fields is the subject of the Jewish Museum in New York’s current exhibition, “The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film.”

Russia’s new political masters wanted to create a new society and a “new Soviet man.” Many of the best-known avant-garde artists embraced this task with enthusiasm: some felt as though their art was the engine driving history. Artists like El Lissitzky, Rodchenko, Stepanova, Goncharova, Malevich, Mayakovsky, and Tatlin—to varying degrees influenced by Cubism, Futurism, and other western European movements, as well as by Russian folk traditions—had been making work that in different ways sought to redefine the very notion of art. In the cultural domain, part of the greater Bolshevik task following the Revolution was to create a new social infrastructure for producing, displaying, and distributing the visual arts. Private art collections were nationalized. Museums, exhibitions and art schools were reorganized; new art schools were formed and there was much discussion about the very concept of the museum. Artists helped create state propaganda on myriad subjects, from politics to literacy to alcoholism and women’s rights.

The blockbuster exhibitions of Russian avant-garde art hosted by the Guggenheim, MoMA, and many European museums over the last twenty to twenty-five years usually covered every possible medium and art form, including architecture and applied arts like furniture and fabric design. In contrast, the curators of “The Power of Pictures” have opted for an in-depth approach to the use of photography—from still-lifes to film—during the first years of the revolution. This allows them to explore an area in which Jewish artists were unusually prominent, and to demonstrate how the avant-garde’s legacy remained visible through photographic works long after all independent artistic organizations were banned in 1932.

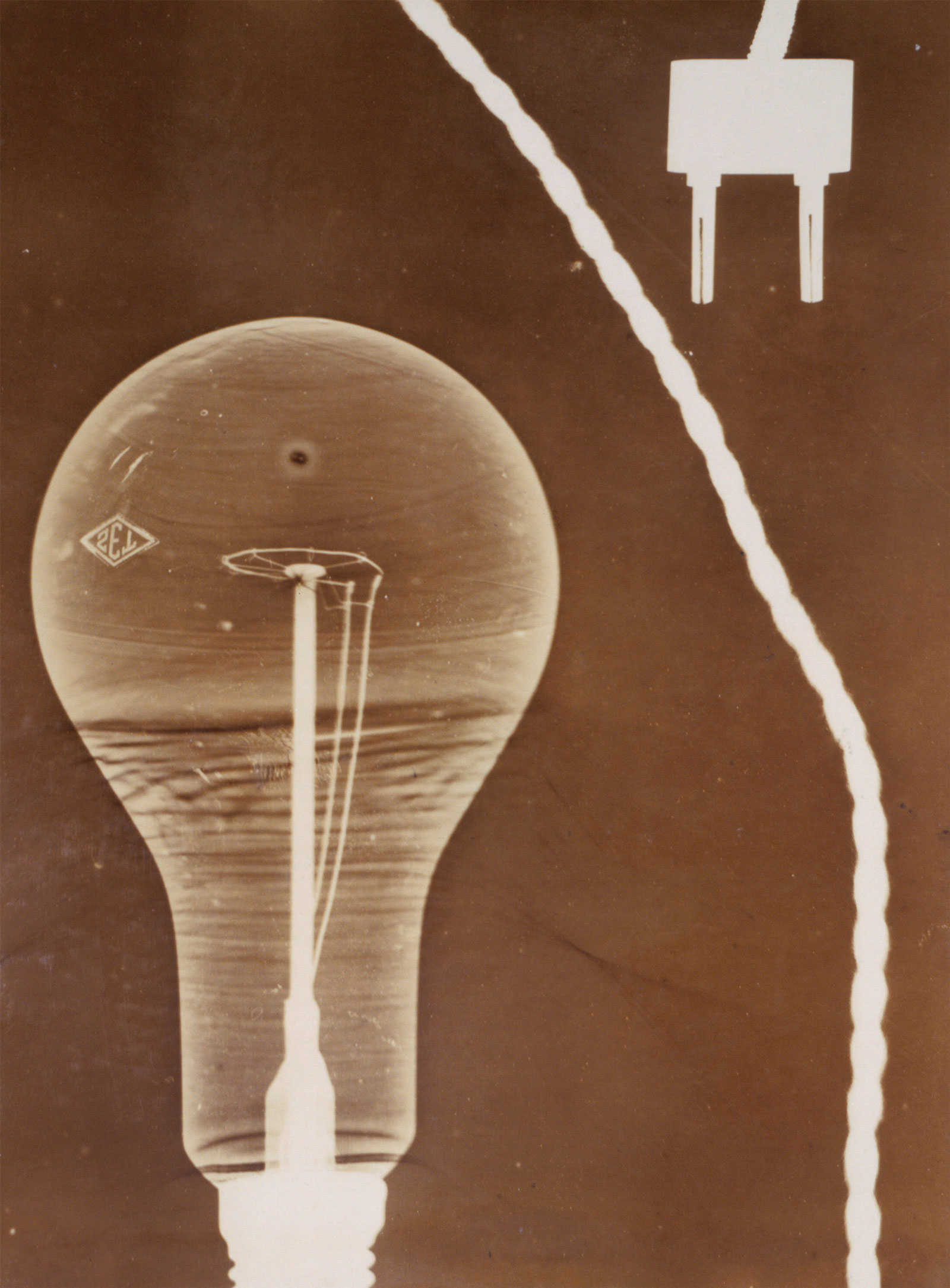

The result is a rich, tightly curated survey of photo-based works that reveals the incredible stylistic diversity of the period. There are photogram “still-lifes” by El Lissitzky and Georgy Zimin that look like eerie x-rays of everyday objects. Some photographs, such as Boris Ignatovich’s Factory (1929) and Georgy Petrusov’s Dnepr Hydroelectric Dam (1934-1935) capture reality in images with such strong abstract elements as to be initially indecipherable; the curving and rectangular diagonals in Petrusov’s photo could be seen as a stylized hammer and sickle from a distance. Оther photographs, like Alexander Grinberg’s soft-focus nude, Sitting Girl (1928), and Georgy Zelma’s Meeting at the Kolkhoz (1929), though quite different in subject matter, are equally atmospheric and verge on the painterly.

The pieces on view include familiar images of military parades, athletes, and sports events, as well as cityscapes taken from every imaginable angle by many different photographers. But there are also photo-reportage sequences from farms, factories, and the colossal Soviet engineering projects of the 1930s, such as the aforementioned Dnepr Hydroelectric Dam and the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal. There are individual portraits of all sorts: snapshots of photographers at work, lying on the ground or holding cameras high overhead to take pictures of parades from surprising angles, which contrast dramatically with romanticized straight-on studio portraits by Moisei Nappelbaum of figures as incompatible as the poet Anna Akhmatova and Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Soviet secret police.

A large selection of posters, photo magazines, book covers and examples of photomontage demonstrates the wide-ranging uses of photography, as well as cinema’s heavy influence on design principles during the first two decades of the Soviet state. The twelve silent films from the period that the curators included, many of them not widely known, offer viewers a rare, first-hand opportunity to observe the mutual influence these media had on each other. In addition to classics of Soviet cinema, like Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and October: Ten Days that Shook the World, and Dziga Vertov’s frenetic, wildly innovative Man With a Movie Camera, they range from a comedy about a country girl and class conflict in an apartment building (The House on Trubnaya), to an expressionistic film based on Gogol’s story “The Overcoat.”

Advertisement

Esfir Shub’s ground-breaking documentary chronicle, The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty, uses actual pre-Revolutionary historical and stock footage from many sources to portray the class struggle that led to the Revolution of 1917. (For those unable to spend enough time at the museum to watch them all, most of the films can be streamed online.) As Jens Hoffmann notes in a very informative catalog essay on the film industry after the Revolution, avant-garde-influenced experimental films were not very popular with the public, which vastly preferred more traditional entertainment. But their subsequent influence on filmmaking worldwide is more than evident.

Photography was the perfect medium for promoting the new state order. Its use in newspapers, magazines, posters, journals, and books as something other than portraiture was a new phenomenon. It was by definition “modern” and “forward-looking”—a non-elitist medium for the age of mechanical reproduction. Though there were photo societies in the early years of the century, there was no “Academy of Photography” dictating aesthetic criteria for the medium, there were no museums, patrons, or collectors of photography or much of a market as such. Photography was not generally considered a fine art form at the time (though interestingly, Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Bolsheviks’ commissar of culture, argued that it was). For this reason, in part, it was an open field that offered unprecedented professional opportunities for Jews.

In his catalogue essay, the Russian art historian Alexander Lavrentiev, grandson of the artists Varvara Stepanova and Alexander Rodchenko, gives a nuanced view of the complex situation in which Soviet photography developed, and provides a map of the period’s “photo landscape.” Photography was dominated by three groups or tendencies, whose aesthetics mirrored, to some extent, the spectrum of political factions on the post-Soviet cultural stage. None of these groups opposed the Revolution, however; initially, in fact, most artists and the intelligentsia supported the regime.

On the aesthetic “right,” the “pictorialists” more or less represented an older generation of traditional studio portraitists and landscape photographers, including Moisei Nappelbaum and Alexander Grinberg, who were often criticized for overly aestheticizing their subjects and approaching photographs like paintings. The “leftists,” or photographic avant-garde, coalesced around Alexander Rodchenko, eventually forming the group “October,” which included Boris Ignatovich, his sister, Olga, and wife, Elizaveta Ignatovich, Eleazar Langman, and Mikhail Kaufman (the brother of filmmaker Dziga Vertov).

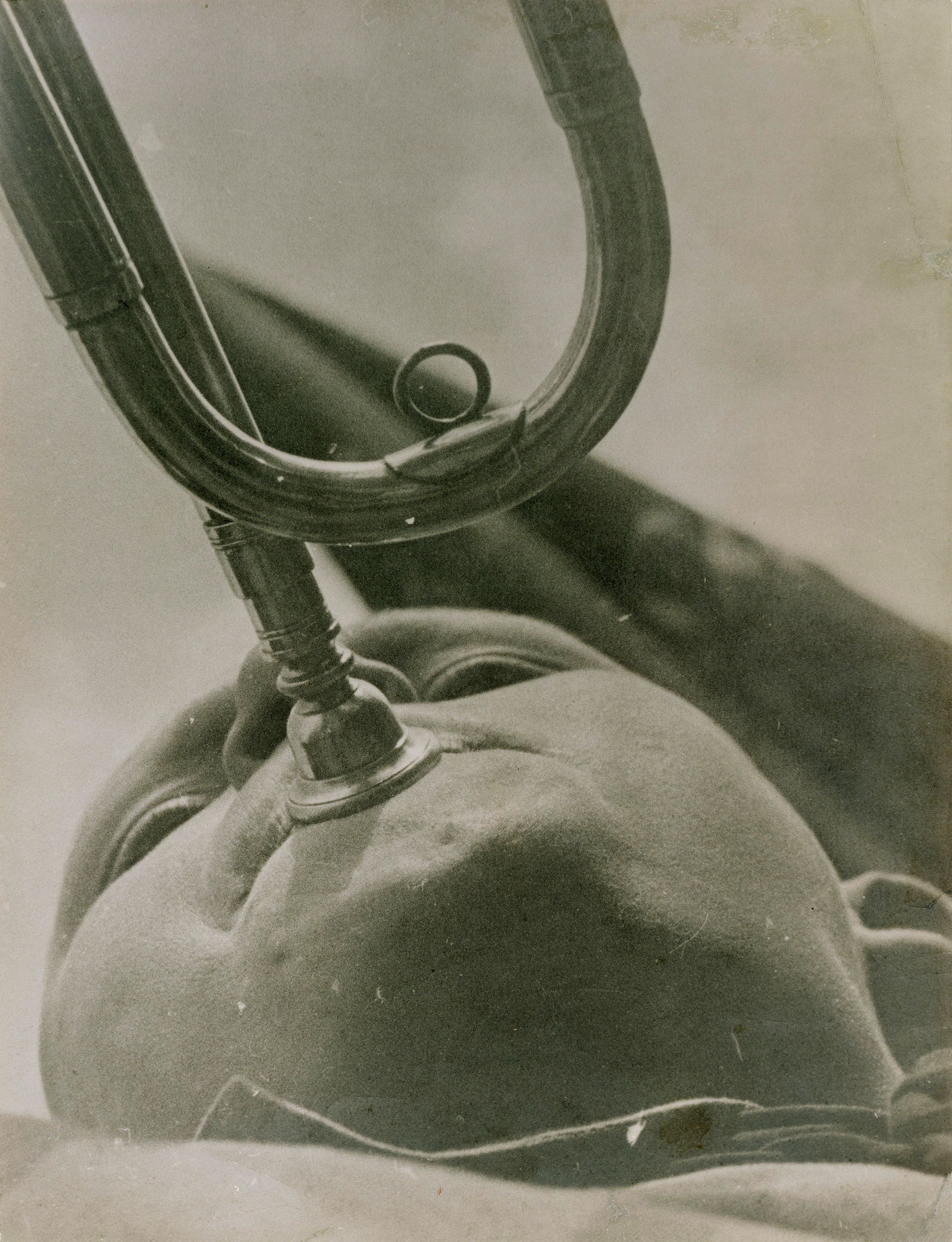

In the early 1920s, Rodchenko abandoned painting for Constructivist design and photomontage, much of it done in collaboration with the poet and artist Vladimir Mayakovsky. As he moved increasingly into “straight” photography, he rejected the complacency of what he termed the “belly-button perspective” of traditional images, be they paintings or photographs. Around 1925, influenced by the Bauhaus photographer Moholy-Nagy, Rodchenko began shooting photographs from odd and unorthodox angles in order to disrupt the viewer’s expectations and force a new perception of reality. (He was later attacked in print for imitating Europeans who were interested exclusively in the formal characteristics of images rather than their social utility.) He produced a highly influential series on his apartment building in central Moscow; some pictures look straight down from a high balcony at the heads of pedestrians in the courtyard; one veers up at a direct vertical along the outer wall to show a man standing on a fire escape. He photographed a young Pioneer scout playing a trumpet from an angle directly below the boy’s chin, emphasizing the powerful outward and upward sculptural thrust of the head and instrument. This now iconic image was criticized at the time for distorting reality and the human form.

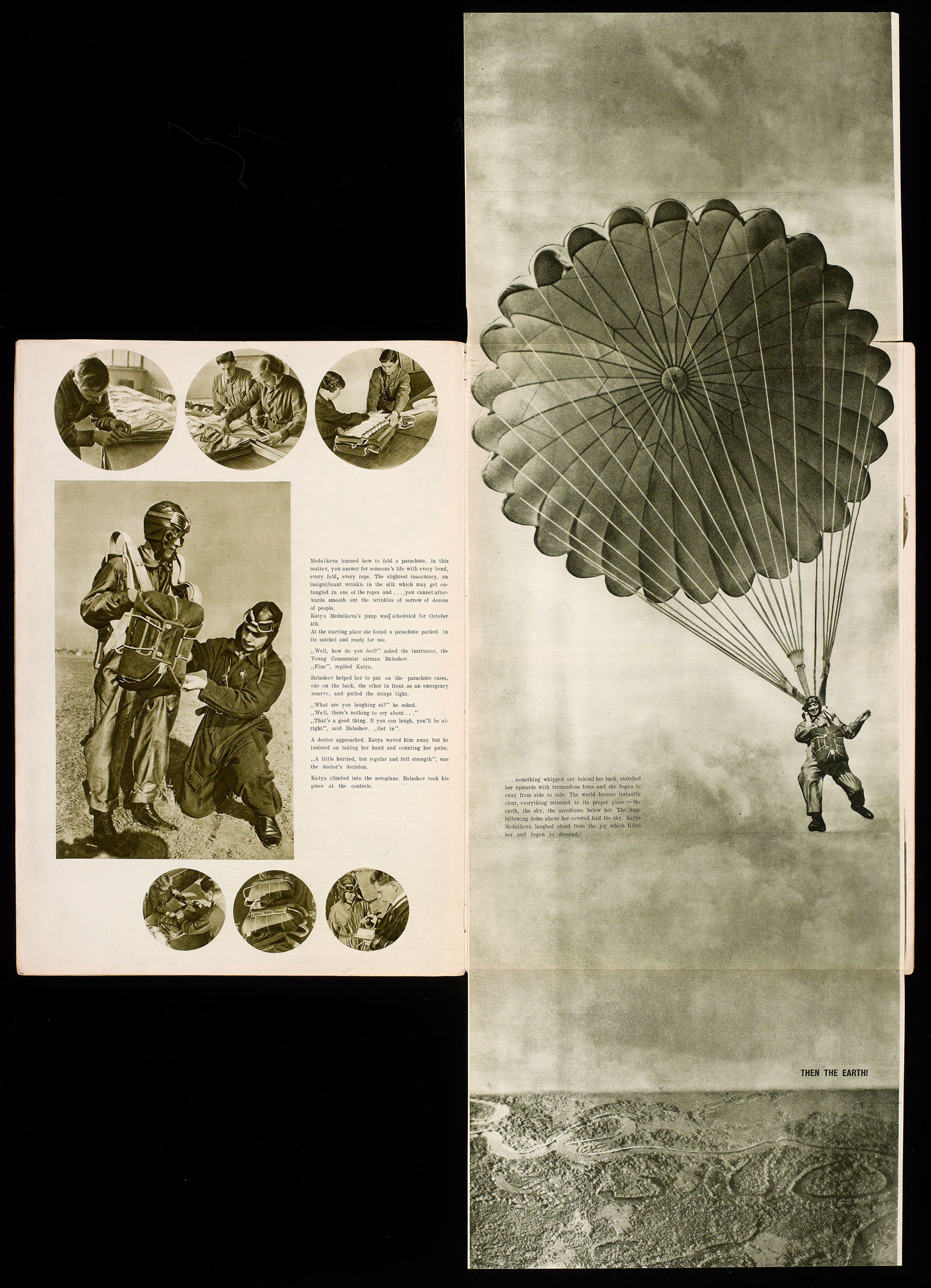

Finally, ROPF (Russian Society of Proletarian Photographers) constituted the political and aesthetic “center.” It included many young Jewish photographers, most of whom remained prominent through the 1930s, World War II, and into the post-war period—Max Alpert, Arkady Shaikhet, Semyon Fridlyand, Georgy Petrusov, Mikhail Prekhner, and Yakov Khalip, among them. They often had no formal training, but learned on the job; unlike many of the photographers associated with October, they were not artists who had turned to photography. ROPF was dedicated to photojournalism that supported the ideological goals of the state with literal narratives, and its most enduring contribution to Soviet photography was the “photo essay.” The first and best known of these was Alpert and Shaikhet’s “Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of the Filippov Family” (1931), which selected photos taken by three photographers over a period of five days in order to represent the most “typical” aspects of a worker’s everyday family life: the children at nursery school, the elder Filippov reading a newspaper and attending a political education class, his wife learning to read and shopping for food, the family moving into a new apartment. This genre became increasingly popular as a propaganda tool. The masses had no trouble understanding it, and editors could easily control the narrative or message.

Advertisement

Despite the existence of “leftist,” “centrist,” and “right” wings in photography, and the use of aesthetic polemics in to gain advantage in political battles, much of the actual work in the show belies the notion that the lines delineating these groups were very clearly drawn. Lavrentiev views the landscape of early Soviet photography as having various peaks and hills, stylistically varied cities, towns and villages, all connected to one another by well-traveled bridges and walkways, and all fed by the same river, comprising the major photo journals and agencies, in particular, Sovetskoe foto (later Proletarskoe foto), running through a valley alongside them.

This rather bucolic description helps explain a striking feature of Soviet photography in the first decade and a half after the Revolution. Perhaps because of the relative newness of the medium, its practitioners were influenced by and borrowed from one another, both in style and content, to a degree unparalleled in the other arts. Arkady Shaikhet’s 1928 photos of the staircase of a new apartment seen from directly above and below (the former appeared on the cover of Ogonyok in 1928) are clearly indebted to Rodchenko’s perspectives, to give only one example. And, as Lavrentiev notes, though Rodchenko’s “angled photographs generated opposition…[they] were infectious and provoked a desire to imitate.”

Members of ROPF made free use of the unusual perspectives generally associated with the October group when it suited their purposes, and both the center and the left groups photographed the same subjects. Modernist compositional principles brought photography closer to cinema, with its mobile, constantly changing viewpoints, as Lavrentiev writes, a fact amply illustrated by the multiple perspectives and focal distances used to striking effect in film posters and book design. Echoes of Anton Lavinsky’s photomontage poster for The Battleship Potemkin can be seen in the juxtaposition of sailor and cannon in Yakov Khalip’s 1938 photograph On Guard. Nearly all of these photographers, regardless of their affiliations, worked together at one time or another on publications like The USSR in Construction, much admired for its innovative use of avant-garde photomontage principles well into the late 1930s.

That “desire to imitate” probably extended to painting, as well: though painting is beyond the scope of the exhibition, throughout “The Power of Pictures” one catches tantalizing glimpses of similarities between photographs, cinematic images, and the paintings of the period. It is tempting, for instance, to see Olga Ignatovich’s dynamic 1930s photo of a soccer goalie blocking a ball in mid-air as the inspiration for Alexander Deineka’s stunning, bannerlike (1.2 х 3.5 meters) oil on canvas, Goalkeeper, 1934. The influence of the avant-garde is obvious in the work of almost every member of ROPF, and in a good deal of the cinema of the time. Victor Turin’s film Turksib (1929), for instance, chronicles a real-life, proletarian epic, the construction of the Turkestan-Siberian railway, but does so in a rhythmic, patterned visual language that owes a great deal to Sergei Eisenstein and Rodchenko.

Throughout the 1920s, multiple political and artistic factions scrambled for limited resources and the ideological approval needed to obtain them. For a while, avant-garde artists occupied positions of power. But as the 1920s progressed, less and less aesthetic diversity was tolerated; by the time of the first five-year plan (1928), which marked the end of NEP and the economic experiment with small private businesses, the ideological polemics and name-calling among artists had become quite fierce and had serious consequences in terms of access to commissions, jobs and patronage. Experimentation of all sorts was being skewered as “bourgeois” and “formalist”—аs “art for art’s sake” that was imported from the West and had no place in the new Soviet world. Ironically, many of the terms used in political attacks against avant-garde artists were similar to those that they had once used in their endeavor to overturn traditional aesthetics before the Revolution.

As Stalin consolidated political power, all of the arts, from painting to poetry, were reined in. The “April Decree” of 1932 put an end to the multiplicity of independent artistic organizations (avant-garde or otherwise) and set the stage for herding all artists, writers, composers, and architects, into national “creative unions.” In 1934, Boris Ignatovich photographed a rather glum Pasternak and Korney Chukovsky at the First Congress of the Union of Soviet Writers, where “Socialist Realism” (a term whose meaning could conveniently be stretched or contracted according to political necessity) was declared the official art of the USSR. The “belly-button perspective” had won out—but it was in photography in its many guises that the perceptual innovations of the Russian avant-garde lived on the longest, to leave an indelible and challenging legacy to generations of artists around the world.

“The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film,” is on view at the Jewish Museum in New York through February 7. It will continue to the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee, from March 11-July 4; and the Joods Historisch Museum in Amsterdam from July 24-November 27. The catalog, edited by Susan Tumarkin Goodman and Jens Hoffmann, is published by Yale University Press.