Some devotees of Richard Wagner have suggested, not wholly in jest, that the best way to enjoy the master’s operas is with one’s eyes closed. For not only have few stage presentations of his monumentally conceived and famously lengthy music dramas ever approached the cosmic sublimity of their underlying compositions, but nowadays it appears mandatory for them to be produced as bizarrely as possible, and despite the composer’s detailed visual instructions to the contrary.

Wagner’s intentions were religiously followed at his annual Bayreuth Festival for decades after he died, but with the rise of Hitler—an avid Wagnerite and Bayreuth regular—the composer’s music became closely associated with Nazism. For example, in the 1930s productions of Siegfried, the avaricious dwarf Alberich was often depicted as a stereotypical money-grubbing Jewish merchant, and many observers saw his sniveling toady Mime as a caricature of the ghetto schlemiel. Adding to these associations were the composer’s own evident anti-Semitic tendencies, expressed in his notorious 1850 essay Das Judenthum in der Musik (Jewry in Music), a diatribe against his principal early competitors, the Jewish-born composers Giacomo Meyerbeer and Felix Mendelssohn. Ironically, the postwar imperative to sanitize the Wagner corpus of its Fascist connotations encouraged other political interpretations that now can seem almost as objectionable as the Hitler era recedes into history.

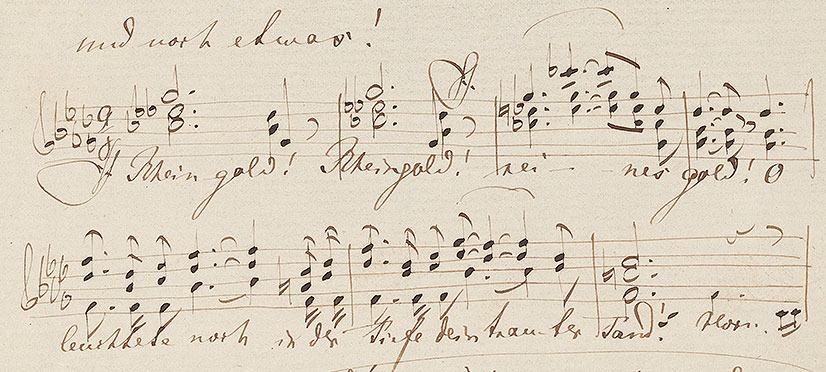

All of which has made the history of the composer’s original conceptions—primary evidence of which is on view in the Morgan Library & Museum’s “Wagner’s Ring: Forging an Epic”—feel like something of a rediscovery. Consider the engravings of the stage décors by the nineteenth-century Viennese artist Joseph Hoffmann for the first complete presentation of Der Ring des Nibelungen in 1876. Conservative though Hoffmann’s set designs are in their realistic evocation of mountain landscapes and a quaint notion of “primitive” architecture (informed by the theories of the German architect Gottfried Semper), it’s hard not to see the Morgan show—in which several dozen letters, manuscripts, and documents trace the three decades from Wagner’s initial idea for the Ring cycle in 1848 to its first public presentation—as a rebuke to the antics that have lately turned this landmark of musical theater into an international freak show.

Forty years ago, the composer’s direct descendants—who still control the artistic direction of the Bayreuth Festival, the all-Wagner summer jamboree he established in the sleepy Bavarian town of Bayreuth—commissioned Patrice Chéreau’s still-influential centennial mounting of the Ring, which caused an uproar among traditionalists but was also widely admired in some quarters and fostered a new school of Wagnerian dramaturgy. In it Chéreau presented the gods, demigods, and mortals of the four-part sequence not as pan-cultural archetypes of human nature, but rather as cartoonish avatars of nineteenth-century capitalism dressed in the kind of comical plutocratic garb the Bolsheviks used to connote enemies of the proletariat. Yet in the opinion of many, this crude neo-Marxist interpretation narrowed the universal implications that have beguiled Ring enthusiasts from the outset.

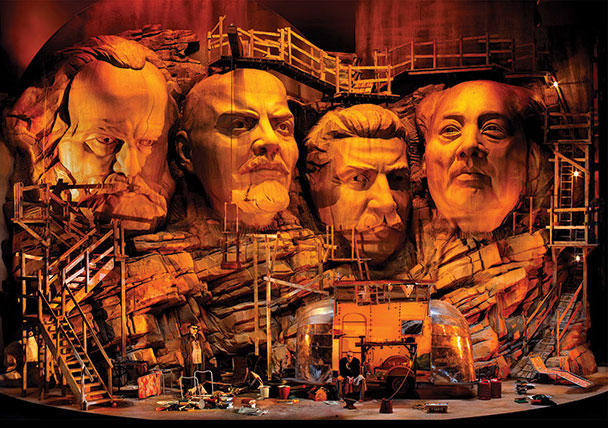

Since then it’s become commonplace to set the Ring cycle not in some vaguely defined primeval world that underscores the saga’s profound mythic power, but rather in outlandish locales calculated to shock. New depths of absurdity were plumbed with Frank Castorf’s 2013 Bayreuth Ring, which marked the bicentennial of Wagner’s birth. Among the settings Castorf depicted were a Route 66 gas station and motel for Das Rheingold, and a pre-Russian Revolution Caspian oil field for Die Walküre. As for Siegfried and Die Götterdämmerung, here is how The Guardian’s Martin Kettle described it:

Erda gives Wotan a blowjob, while Siegfried wakes Brünnhilde beneath gargantuan Mt Rushmore-style sculpted heads of Marx, Lenin, Stalin and Mao on a stage revolve that periodically transports them into Honecker-era East Berlin, where crocodiles hump one another and the hero and heroine drink themselves into a loveless operatic climax.

New York City—a big Wagner town since the mid-nineteenth century, when its sizeable German immigrant population formed a ready-made audience for the composer’s operas— has had its own recent Ring fiasco: Robert Lepage’s staging introduced between 2010 and 2012 at the Metropolitan Opera. All four installments of this $40-million extravaganza were dominated by a mechanized forty-five-ton set, which The New York Times dubbed the “Valhalla Machine.” Designed by Carl Fillion (who has worked with Lepage for Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas), this flange-beamed contraption cost around $16 million but proved hugely disruptive to the musical proceedings because of the loud noises it often emitted, to say nothing of its sporadic malfunctions, when on several occasions it subverted the drama’s high points.

Advertisement

But as the Morgan exhibition makes clear, the financial demands imposed by Wagner’s grandiose vision have been central to the Ring from its inception. Among the many fascinating documents on view are several dealing with money matters. Here—along with the expected musical manuscripts and source material for the libretto, which draws on Nordic legends—we can see one of the composer’s many begging letters to would-be backers, in this case Franz Liszt’s rich lover, Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein; an invitation to an 1853 Zurich reading of the tetralogy’s text (which Wagner also wrote), on which the author—avid for every last Swiss Franc he could hustle—scribbled a postscript that children under one year old were also welcome, lest their mothers stay at home; and an 1881 document in which his biggest creditor, King Ludwig II of Bavaria, forgives a debt payment. (Here the sovereign’s loony-looking signature seems to fully justify his “Mad” sobriquet.)

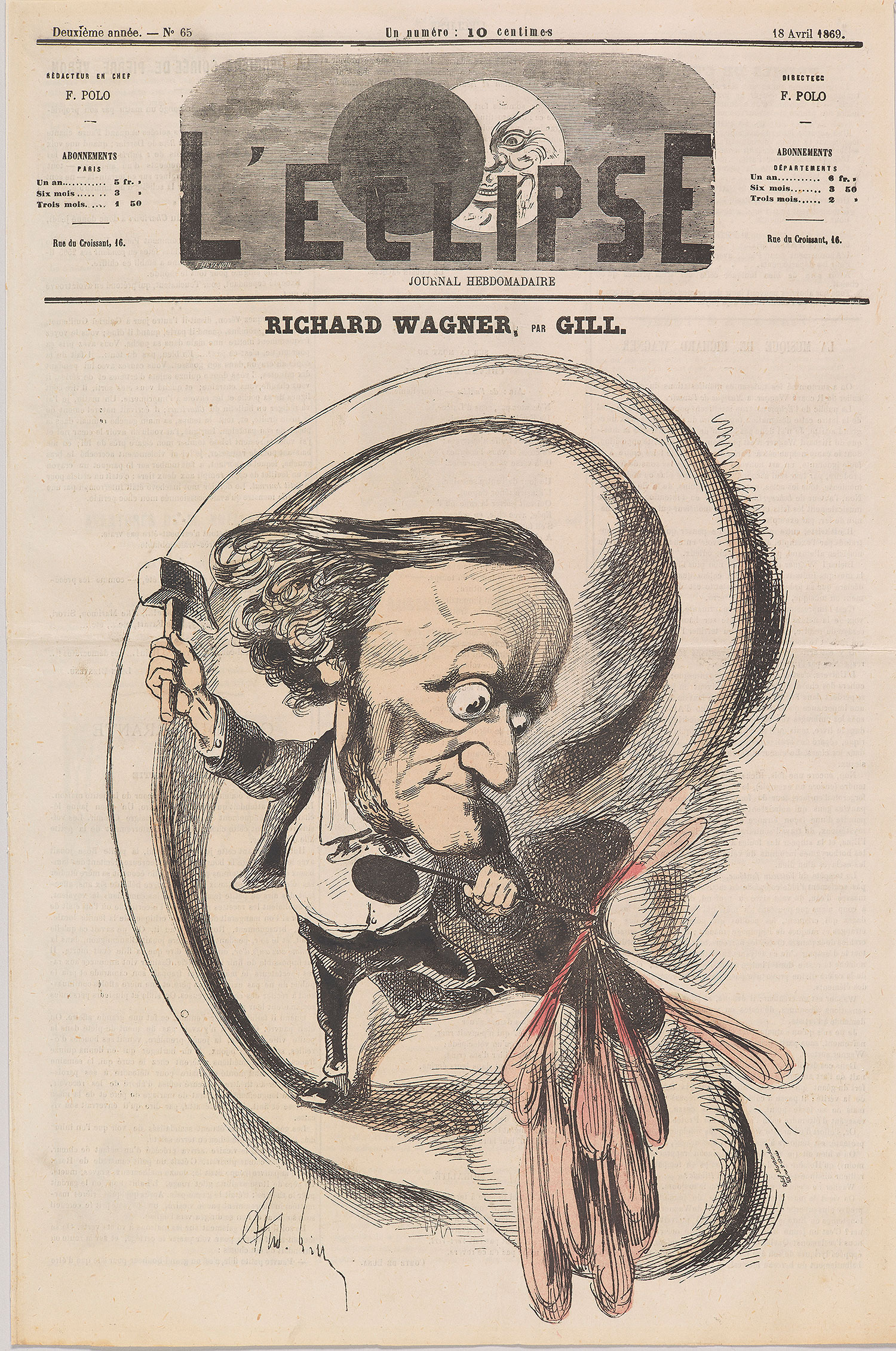

Wagner— a posturing dandy, short in stature but with an enormous, leonine head and prominent profile, much like Leonard Bernstein a century later—was catnip to cartoonists, and in addition to Richard Wagner in der Karikatur (a 1907 compendium of visual lampoons) the Morgan exhibition displays several of the best-known satirical images of his time. Among them are André Gill’s 1869 engraving of the composer driving a spike into an enormous, blood-gushing ear, and Honoré Daumier’s no less palpable 1868 depiction of a Munich audience being blown backward in their seats by a maelstrom of fragmented musical notation, a sensation I’ve happily experienced on several unforgettable Wagner evenings.

At the front of the single large gallery in which the show is installed, a video screen plays taped excerpts from the four operas, including the recent Met Rheingold and an orchestrally superb 1980 Bayreuth Walküre conducted by the late Pierre Boulez. Unfortunately there are no clips from the revolutionary postwar Bayreuth Ring cycles directed by the brothers Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner, grandsons of the composer who—once Allied authorities allowed this erstwhile nest of Nazis to reopen in 1951—took over the festival from their mother, Winifred Wagner, a close and unrepentant friend of Hitler’s who privately referred to him as “U.S.A.”: unser seliger Adolf (our blessed Adolf).

The Wagner siblings’ starkly minimalist productions—in several instances the stage was left completely bare, and lighting alone defined some indoor or outdoor space—reflected two harsh realities: a lack of funding, and the need to avoid any representational feature that could be interpreted as political, given how compromised the Wagner legacy was. Significantly, these stripped-down stagings, which owed much to the reductive modernist concepts of the Swiss stage designer Adolphe Appia (1862-1928), had a purifying effect that was quite intentional in shifting audience attention toward the Ring’s penetrating psychological aspects and away from the impossible stage business—swimming mermaids, flying horses, a fire-breathing dragon, and a talkative bird, among other fantasies—that has always bedeviled directors.

Like the best abstract art, the New Bayreuth Style, as it was dubbed, allowed viewers to project their own interpretations onto a nearly blank canvas, and to draw illuminating conclusions of their own about the deeper meaning of what they saw before them. The pendulum theory of culture—which holds that action and reaction reflexively animate stylistic swings as broad as those from Rococo to Neoclassical and Pop to Minimalism—might indicate that after every last anachronistic dystopia has been exploited as a stand-in for Valhalla we might finally see a return to undistracting theatrical values more closely aligned with Wagner’s gloriously transcendent music of the spheres.

“Wagner’s Ring: Forging an Epic” is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum through April 17.