“The only thing about America that interests me is Coney Island,” Sigmund Freud is supposed to have said—and the itinerary of Freud’s 1909 trip to America did include a visit to Dreamland, then the newest of Coney Island’s original three amusement parks.

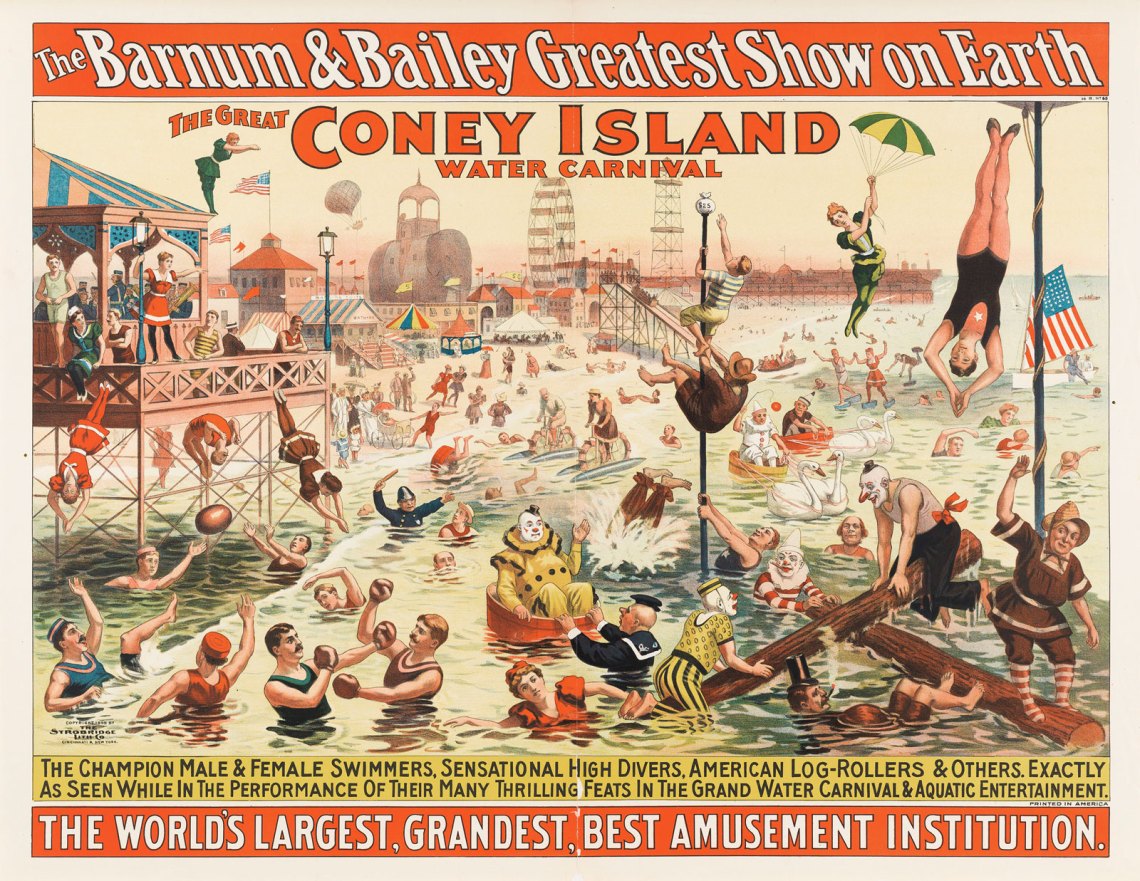

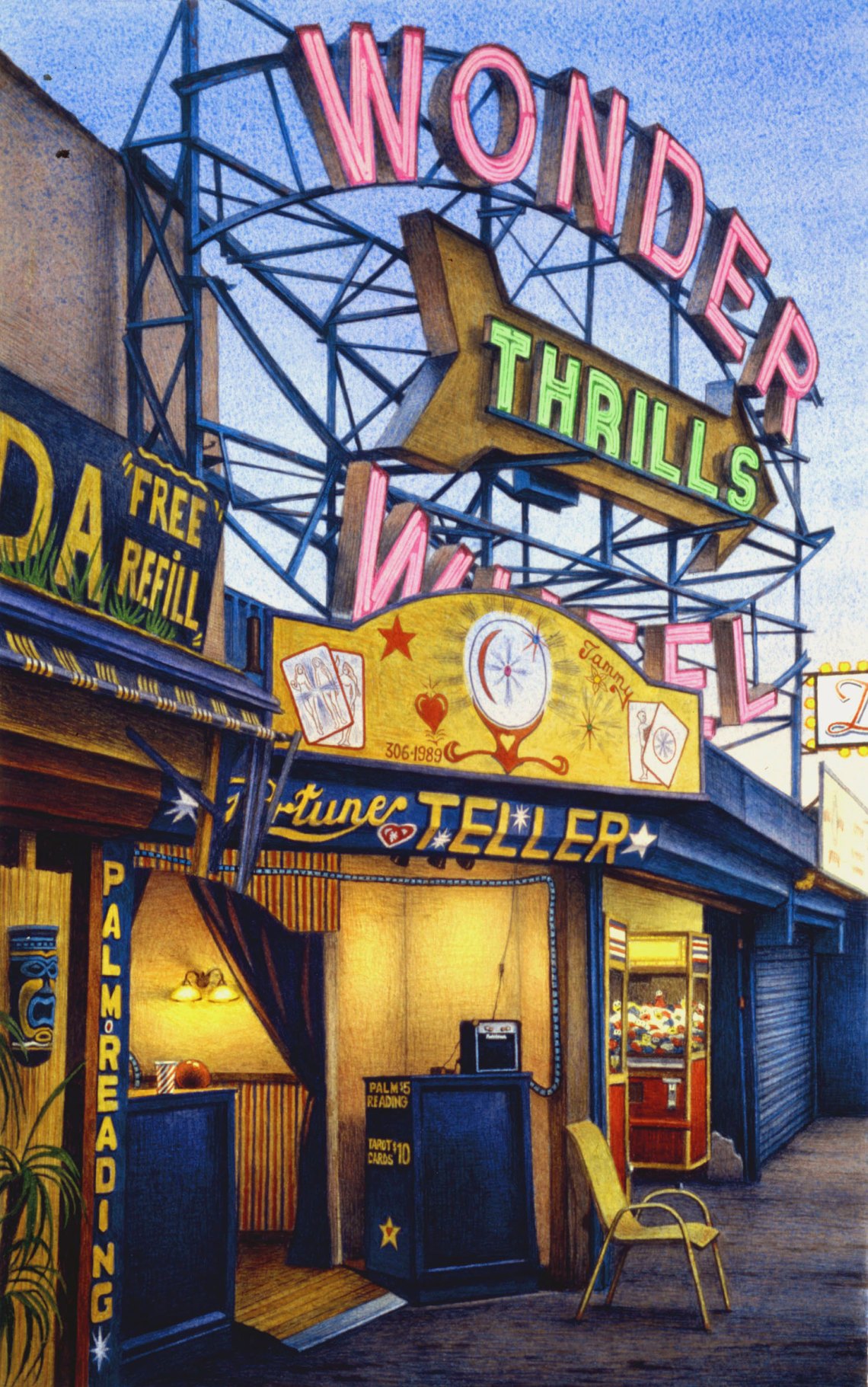

Perhaps for Freud, Coney Island was America—a realm where fantasy was made material and the pleasure principle ruled. So it is with the bountiful exhibition “Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861-2008,” at the Brooklyn Museum through March 13. Only tangentially concerned with the evolution of this stubby peninsula off Brooklyn’s south shore from unspoiled beach to exclusive resort to a raunchy playground for New York City’s multitudes to a stubborn remnant of past glory, the exhibition gives us less the historical Coney Island than a place where artists might ponder the spectacle of democracy at play. Its subject is the mental construct “Coney Island”—an illusion filtered through such earthy sensibilities as the tabloid photographer Weegee, the American scene painter Reginald Marsh, or the anonymous artisans who created the banners and signage for Coney’s attractions.

As befits a dreamland, the exhibit—curated by Robin Jaffee Frank, who also wrote much of the show’s excellent, richly illustrated catalogue—is a mix of artifacts and artworks and a trove of suggestive juxtapositions. One passes from a gallery devoted to late-nineteenth-century paintings of Coney Island’s pristine dunes and barely developed beaches to a raucous head-on roller-coaster ride from the 1935 Hollywood movie The Gilded Lily.

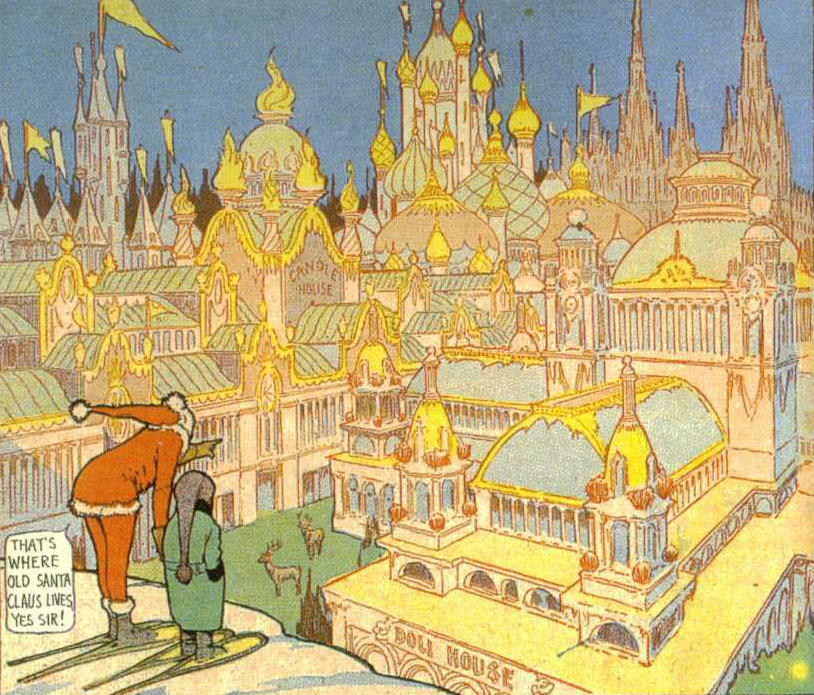

Beyond, a “gambling wheel” with a sinuous dragon motif, used in a roulette-like game of chance, from the early twentieth century, is placed next to the visual tumult of Joseph Stella’s oil painting Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1913-1914), a garish frenzy of near-abstract forms, the whirligig epitome of Fun House futurism. Scenes from the one-reel Edison comedy Rube and Mandy at Coney Island (1903) merge with Leo McKay’s adjacent and contemporaneous panoramic painting of Steeplechase Park; a 1910 wooden cut-out cartoon of Mae West and Jimmy Durante, both of whom got their starts in Coney Island “concert saloons,” is positioned opposite a selection of roughly contemporaneous Sunday pages by the master draughtsman Winsor McCay, whose gorgeously inventive comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland was surely the greatest graphic expression of fin-de-siècle Coney.

Dreamland burned to the ground in 1911. In 1921, after the Brooklyn Rapid Transit company extended its street cars and subway lines to Coney Island, the boardwalk opened, along with numerous hot-dog stands and tawdry amusements. “Huge masses of people were arriving,” Joseph Heller wrote in his memoir of growing up in Coney, “first tens of thousands on summer weekends, then hundreds of thousands, finally a million and more…” The elegant fairyland of Dreamland and Winsor McCay became something more vulgar, albeit a source of folk expressionism and found surrealism for American painters.

“Visions of an American Dreamline” includes rows of ball-toss targets and vitrines of postcards. A lurid fragment from the frontage of the Spook-a-Rama ride is placed cater-corner to Reginald Marsh’s more subtly strange watercolor Riders in a Mermaid Tunnel Boat (1946). The show has eight pieces by Marsh, the corn-fed Rubens, primarily a painter of tumultuous throngs. Unlike the near-apocalyptic mobs of other artists, Marsh’s multitudes are largely composed of sturdy young women. Pip and Flip (1932), a typically crowded painting, features a poster in which, dolled-up and bright-eyed, the eponymous twin microcephalics are portrayed as cute, curvaceous Martians—at least on their poster.

The real Pip and Flip can be glimpsed in an excerpt from Tod Browning’s Freaks, the least likely horror film MGM ever released, also from 1932. The clip is part of a niche devoted to Coney’s sideshow, which, in addition to several official-looking posed photographs by the circus photographer Edward J. Kelty, includes an undated, rather stolid painting by Abraham Walkowitz of a barker exhibiting his human anomalies and a livelier image of a similar display by the satiric lithographer Mabel Dwight. Another small gallery is devoted to the 1904 public electrocution of the rogue elephant Topsy, an event that was filmed by the Edison Company (which also supplied the electricity).

Coney Island peaked as a people’s playground during World War II and began its slow decline when the largest of the amusement areas, Luna Park, burned to the ground in the summer of 1944. Although Weegee’s stunning news photo of the ruins, showing two forlorn painted hearts above a lone fireman in a sea of wreckage, gets smaller play than it might, the image of absolute devastation haunts the exhibition’s final section. Here uncanny magic realist paintings—George Tooker’s pieta under the boardwalk, Henry Koener’s trick mirror barker’s booth (both 1948)—and photographic evidence come to the fore.

Weegee and Morris Engel, his sometime colleague at the leftwing tabloid PM, are the show’s best-represented photographers. The other photographers constitute something of an American honor roll: Diane Arbus, Bruce Davidson, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Mary Ellen Mark, and Gary Winogrand. Most of their work focuses on bodies sprawled on the beach or the dialectic of the couple and the crowd. Frank’s bathers might be corpses, and Arbus, who worked inside the House of Horrors ride and the wax museum, made photographs as creepy as the excavation of a dead planet.

The same gallery is notable for its reconstructions—the lovingly detailed, klezmer-scored Coney Island scene from Paul Mazursky’s 1989 adaptation of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Enemies: A Love Story, and a number of wacky, good-natured paintings and assemblages by the ruckus artist Red Grooms, including his versions of old-fashioned postcards and the photos Weegee took of the World War II–era Coney Island crowd from a vantage point on the Steeplechase Pier. (Steeplechase closed in 1964 and was demolished a few years later by the real estate mogul Fred Trump, father of the Donald.)

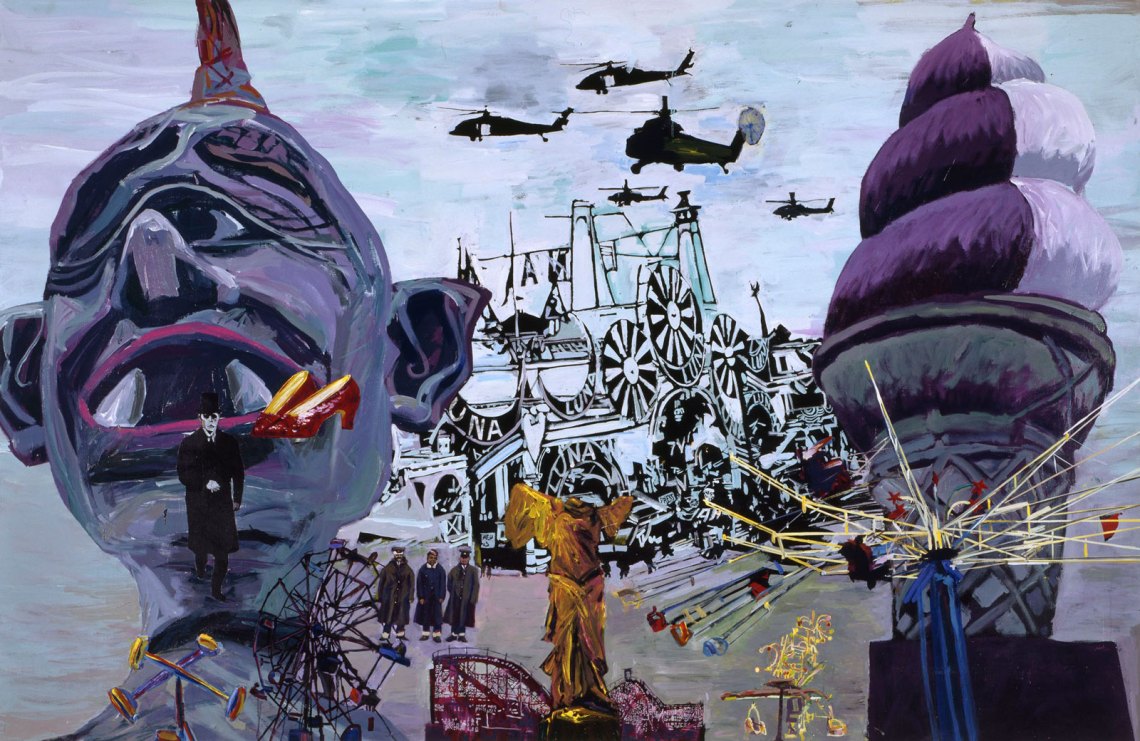

Grooms’s forced cheer notwithstanding, the show ends on a note of dispirited fragmentation. A dark-skinned youth flings himself into the ocean in the graffiti-artist Daze’s 1995 canvas “Coney Island Pier.” The cyclops head that, swiveling and chortling outside the Spook-a-Rama, was a 1950s Coney Island landmark, is present both as its diminished self and as a klutzy demon in two of the political expressionist Arnold Mesches’s banner-sized canvases, Anomie 1991: Winged Victory (1991) and Anomie 2001: Coney (1997). Once a carnival king, the horned, fanged gargoyle is just a hunk of detritus blowing in the wind.

“Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008” is at the Brooklyn Museum through March 13. The catalogue to the exhibition is published by Yale University Press.