In recent years, though, an exclusive and meticulously judged skateboarding event has gained traction—one that now includes men and women. Street League, a contest series sponsored by Nike and broadcast by Fox, is dispersed across the year in multiple cities. Apart from an initial open competition, the series is invite-only, its roster built up of some of the most elite and contest-proven skaters from around the world. Upon landing a timed course run or, in one section, a single move, a score is immediately broadcast on the stadium screens overhead—a one-decimal number between 1 and 10, with an automatic 0 if you don’t land the attempt properly and anything 9 or higher placing the skater in the prestigious “9 club.” Meanwhile, commentators explain specific tricks and their origins (a friend of mine jokes that skating’s conceptual and combination-heavy lingo is like German), dissect why they were done well or not over a replay, and break down the mental atmosphere. At the conclusion, a trio of mini-skirted young women, costumed by a hosting energy drink, hand an oversized check to the victor. The prize is now at $200,000, $300,000 for the final Super Crown World Championship.

Street League isn’t the first skating contest to echo mainstream professional sports, but it feels like the most significant. Unlike the X Games, which has grouped skateboarding together with sky surfing and bungee jumping and something called the Eco-Challenge, Street League was conceived by a skater, the respected former pro Rob Dyrdek. (In the early nineties I saw him, together with the Filipino-American skater Willy Santos, destroy our skate park in Canberra, Australia.) Unlike contests that include bowl or halfpipe divisions, it’s dedicated wholly to street, a form of skating that abounds in a precision and subtleties not easily apparent to the lay viewer. But Street League is also unique for its connection to the state of skateboarding now, its wide popularity, and the skill level of its top participants, which practically defies belief. If skating moves past its perch on the shortlist for the 2020 Olympics—the decision is set to be announced in August—one senses it will be in part because Street League has already shown how that might look. Not that it’s a foregone conclusion, though, or even uniformly desired. For instance, some skaters have put together an online petition to keep skateboarding out of the games. (My name’s on it, though I understand why some feel differently. After all, snowboarding, whose tricks are largely derived from skating, has been in the Winter Games since 1998.)

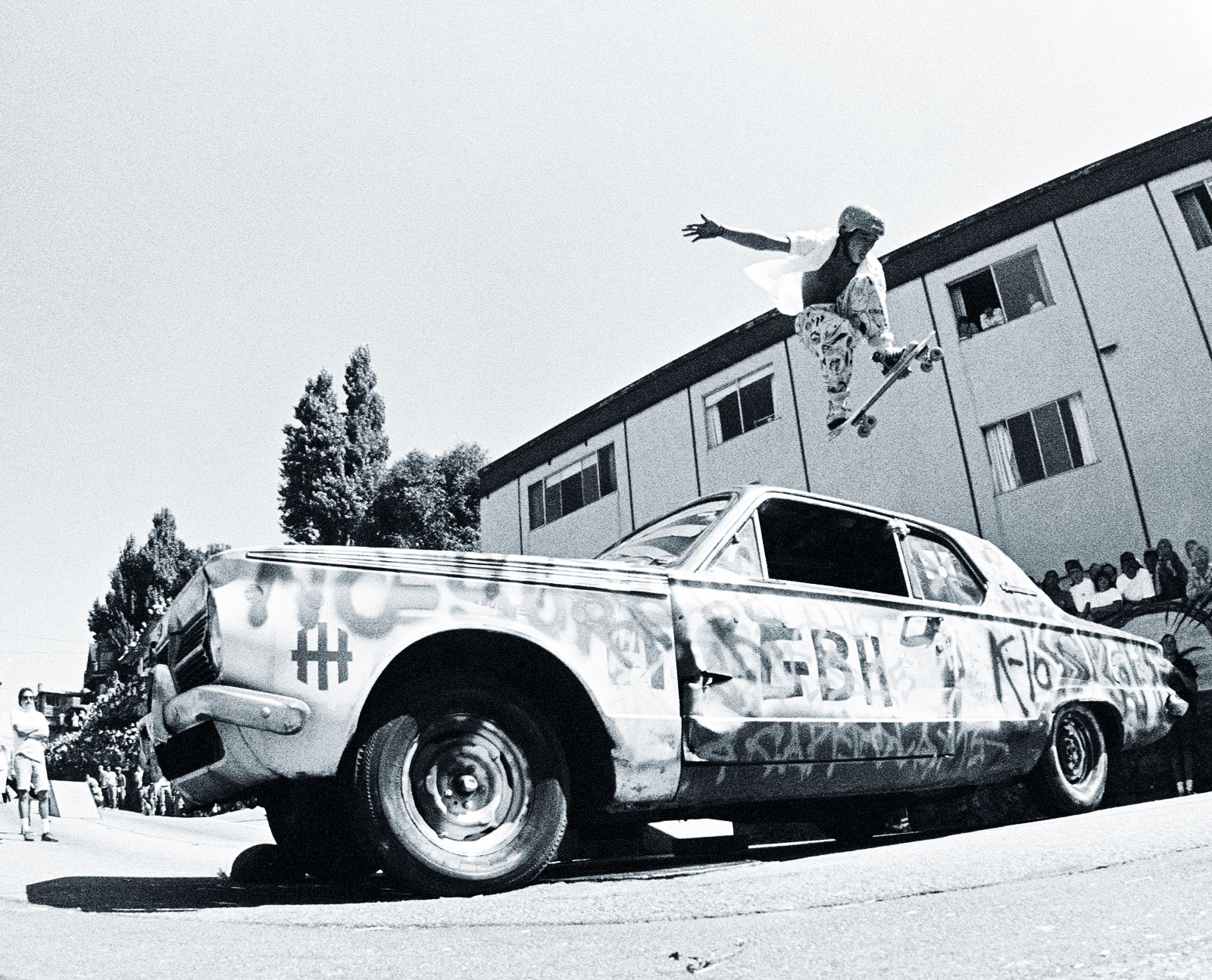

To grasp why Street League can look so surreal to earlier generations of skaters, it helps to know what contests were like back when skating was more obviously a world of misfits, rebels, and eccentrics. Voices from the Seventies tell of being spit on mid-performance by older peers; later, arena events could mean skirmishes with security, and it’s no secret that a few of the sport’s most revered pros liked to toke joints between runs. (In amusing contrast to other sports, and hinting at a parallel with popular music, this sometimes just added to their reputation.) One of the first modern street contests took place in Sacramento, on a scorching day in 1985. Captured in Powell Peralta’s storied video Future Primitive, the setting is a grease-filled parking lot, some curbs, and a bunch of patchy ramps. A poor beat-up old car gets some use—cars became a staple, to be further abused after they’d been aired over or ridden on. The distinction between audience and the riders is fluid: at one point, Lance Mountain pulls a triumphantly long handstand ride right into a standing crowd, who seem pleased to receive him. Around the same time, a number of halfpipe events took place in people’s backyards; viewers watched from wherever they could—on a rooftop, in a tree.

In fact, skate contests have been around almost as long as skateboarding. Some aspects have always been quantifiable, with barrel jumps and slalom races in one decade, and high air contests, complete with ladder-size measuring sticks, in another. In skatepark bowls, perseverance in endless head-to-head runs could sometimes determine a skater’s rank. For the most part, though, there’s been shrugging of shoulders at an inherently subjective task, and little pretense that contest rankings reliably reflect ability. This has been held to even by those who have won dozens of them—Rodney Mullen, to give an illustrious example, threw away his many first-place freestyle trophies, “because I hate them.” Even in the contests themselves, the atmosphere has often appeared more to the point than the results. Many events over the years have been memorable chiefly as jams or get-togethers, where the best or most talked-about tricks often occurred in the practice or post-sessions—they were no less applauded for it. A contest was remembered as the one where someone rode the ramp with a board on fire, pulled off a surprising new trick on a salvaged filing cabinet, or leapt into a quarter-pipe from a high ceiling rafter.

Advertisement

Slowly and almost imperceptibly, though, a new order of money began to enter the equation. The last time skating was conspicuously popular was, I think, in 1987 or 1988—a decent prize purse for a pro ramp event then was five thousand dollars. (Granted, pros could make close to twenty grand a month in board sales, but these were few and the period short-lived.) Nowadays, in what feels like a different boom, winning certain contests might land you the down-payment for a house. The old energies are nowhere near absent from skating, or even from other skating contests, but the very idea of a competition like Street League would have sounded absurd not that long ago. What happened?

A full answer would need to take various developments into account, but one is the gradual mainstreaming of alternative sports. When the X Games, originally “The Extreme Games,” began in 1995, many skaters, observers, and would-be participants both, were wary: this had to do with the contest itself, its jumble of scarcely related activities, like BMX and barefoot water-ski jumping, but also that moment in skating, which was particularly off the radar and fixated on raw street scenes. The X Games aired on ESPN; to make matters worse, initially the street courses favored ramp riders. Transition riders, however, were mostly grateful for the chance of a paycheck—during a stretch in the early Nineties, Tony Hawk, who since the mid-eighties had been something like the Michael Jordan of skating, could receive as little as $50 for a demo.

The contest continued, and as time went on, controversial elements were negotiated and smoothed. One era graded into the next, in which skaters became familiar to a wider public (and vice versa) through video games, televised contests, and even reality shows. When Street League arrived in 2010, it was actually partnered with the X Games, which by then was reaching a television audience in the millions and no longer raised insider hackles.

Previously only familiar with highlights, I followed last year’s Street League in its entirety. The series ran from May to October, with events in Barcelona (a beloved locale in skating for its spacious modern plazas), Los Angeles, Newark, and Chicago. Happily, the format was pared down compared to some other years—it consisted of just runs and a “best tricks” section. Women competed for the first time, a development announced only before the final contest. Although there were a number of women pros in the Seventies, there have typically been far fewer female skaters than male ones. Participation would seem to be rising, though, one of various points that make the present moment in skating especially lively and interesting.

The first Street League women’s title went to the charismatic twenty-one-year old Leticia Bufoni, from Brazil. Given her ability and assurance, this surprised nobody, but there was stiff competition, plus a refreshing breadth of styles of skating—something the men’s roster could use more of—from riders such as Alexis Sablone, Lacey Baker, Pamela Rosa, and Vanessa Torres. In a subsequent interview, Torres, whose transition skills and frontside boardslides down the handrail were among the highlights of her division, spoke frankly about the sexism she’s observed within the skate industry—maybe the popularization of skating will help bring some inadvertent gains?

In the men’s bracket, it sometimes looked as if Luan Oliveira might outstrip the usual candidates for first place. Often referred to simply as “Luan,” Oliveira has emerged from a tough background in Porto Alegre to become one of skating’s foremost pros. A televised skating contest, especially one with back-and-forth rectangular courses and an abstract, video game-like aesthetic, risks a boring predictability. But Luan combines his phenomenal ability and high “pop” with an enjoyment that’s so clear as to be infectious. When needing to slow down a little, he’d instinctively bust an old-fashioned power slide; after unleashing a hard trick nobody had seen him do yet, the commotion made it seem as if everyone’s good friend had pulled a move they’d long been trying.

Though Luan ended up winning the event in New Jersey, the championship ultimately went to someone else. It wasn’t Chris Cole, an affable and self-deprecating East Coast skater with an enormous bag of tricks, nor Nyjah Huston, who has won a full sixteen of twenty-six Street League contests. (An undeniable prodigy who goes big as a matter of course, but also someone whose style began as kind of clinical, Huston divides critical opinion.) Nor was the winner Shane O’Neill, from Melbourne, Australia, with his lightfooted and extraordinary technical prowess, or the stylish hometown favorite who’s in line for a win, Chaz Ortiz. Paul “P-Rod” Rodriguez, the likable star face of Nike’s skateboarding arm, is often a force, but he couldn’t stay on his board as much as usual. No, the title went to a rookie, Kelvin Hoefler from Sao Paolo. Brazilians!

Advertisement

While I enjoyed tracking the year’s contests more than I’d expected, I’m still unsure what to make of the series’ meaning for skating as a whole. Street League disciplines street skating into something professionalized and systematized—qualities that kids used to dive into skateboarding to escape. On the other hand, the mood at the contests is more relaxed and fraternal than in a lot of other pro sports, and the cultural mix in sync with skating’s: in the series, South Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and mixed-race kids often seem to outnumber whites. Texan Cody McEntire skated every run with a toothpick in his mouth; Vanessa Torres competed wearing a Gay Pride shirt, and with a portrait in honor of a late friend on her griptape.

One way of looking at Street League, perhaps, is simply to see it as but one of several different directions skating is going, not all of them mutually exclusive. Many who don’t care for the series will still follow some of its contestants, especially the more fun and imaginative ones like Luan or Ishod Wair. In regular life, an abundance of people are pushing the boundaries of classic street skating, while other kinds of competitive events, like bowl jams, offer an engaging mix of new talent with still-charging veterans. In this new climate, skaters are more consistent and well-rounded; the completely sui generis materialize, and talent develops freakishly early and also endures longer than ever before. And while it’s true that the Internet and Instagram can give the impression of a competitive frenzy, all death-defiance and superhuman technicality, there are many skilled skaters who enjoy readopting old-school tricks–like Ollie Impossibles, or, on transition, the even more time-honored Backside Boneless—and who above all seek a spontaneous and fresh approach to terrain.

Take the bowl session, light show, and concert that unfolded at the Kennedy Center last August. Led by the jazz pianist Jason Moran, the event highlighted skating’s ties to music. About a foot away from the wooden bowl out front of the center sat Moran’s Bandwagon Trio, adding and changing guests at will: the pioneering, black street skater Ray Barbee put down his board and picked up a guitar, and H.R., the lead singer of the hardcore D.C. reggae-punk act Bad Brains took the mic. In and out of the bowl flew a host of figures young and middle-aged, iconic, local and unknown, their pace and ideas shifting against the improvisational sounds. If Street League approaches skating as another form of athletics, here was a tribute to it as subculture and art.

A constant of skating is that it’s always changing. Sometimes it seems for the better, sometimes the worse, yet either way there have always been people out there having fun and being creative. Skating’s forward and unpredictable advance is a bit like the act of riding itself. One second you’re going this way, the next you’re turning that. Quick, better move your front foot forward so as to bump off a crack, slide over here on this thing, see what comes up next.