What are the limits of international accountability for crimes of war? And what does it mean for the local populations in question? As human rights groups prepare for cases which might be brought when the war in Syria ends, the last few weeks have brought some stark results from the Balkan wars of the 1990s.

First was the March 24 conviction of Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, the most senior figure from the wars to be convicted by the UN’s war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. The court in The Hague found him guilty on ten of eleven charges—including genocide for the executions of 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys from Srebrenica in 1995. Then came the baffling acquittal, on March 31, of Serbian ultra-nationalist Vojislav Šešelj, who was a leading advocate of ethnic cleansing and whose militia was deeply involved in campaigns to drive out Croats and Bosniaks from regions claimed for a Greater Serbia in the early 1990s. Similarly shocking was the January murder conviction of Oliver Ivanović. Sent to jail by judges of the EU’s law and justice mission in Kosovo, the politician Ivanović had done much to work for reconciliation between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo. Something seems amiss here.

Faced with these erratic results after so many years, few in the Balkans are happy with the work of The Hague tribunal or local ones, except perhaps the victims who have testified in court and whose words and experiences are recorded for posterity. Nor is there much indication that leaders in war-torn countries today, like Syria, are even listening. What has been less predictable, however, is the extent to which some people, at least in Serbia, Bosnia, and Kosovo, are themselves beginning to reassess what took place in their countries during the 1990s, even as there appears to be little political will in their countries to see that justice is fully done.

As it happens, the recent verdicts in The Hague have coincided with a series of stunning new films about the wars made in the region. There is no single explanation for why this is happening now, and it would be wrong to exaggerate how widespread the phenomenon is. But these works—including both documentaries, and feature films—suggest that some are not prepared to forget or gloss over a past that is still dominated by a victim mentality in each of the countries in question. Meanwhile, an important new book has given us the full story of how men like Karadžić were finally tracked down—and why it took so long.

In The Butcher’s Trail, Julian Borger, the world affairs editor of The Guardian and a former correspondent in Bosnia, has pulled together the many different strands of the complicated effort to bring suspected war criminals from the Balkans to justice. One way or another, every single one of the 161 suspects on the list of the UN’s war crimes tribunal was eventually accounted for. The so-called big fish included the Croatian general Ante Gotovina, but inevitably the most interesting stories are about the leading Serbs—Karadžić, his military commander Ratko Mladić, and their boss of bosses, Slobodan Milošević. Milošević died in 2006, before his trial had finished; Mladić’s trial is expected to wind up next year.

Accounting for each of these suspects was no mean feat, given that the tribunal had no force of its own to arrest the people it was indicting. It had to rely on UN troops in Croatia, soldiers from the NATO peacekeeping mission in Bosnia, national police forces if the suspects were no longer in the region, and the intelligence agencies of any countries prepared to help. “More than half the suspects were tracked down and captured,” writes Borger. “Others gave themselves up rather than lie awake every night wondering whether masked, armed men were about to storm into their bedroom. Two committed suicide. Others decided they would rather die in a blaze of gunfire and explosives than be taken alive.”

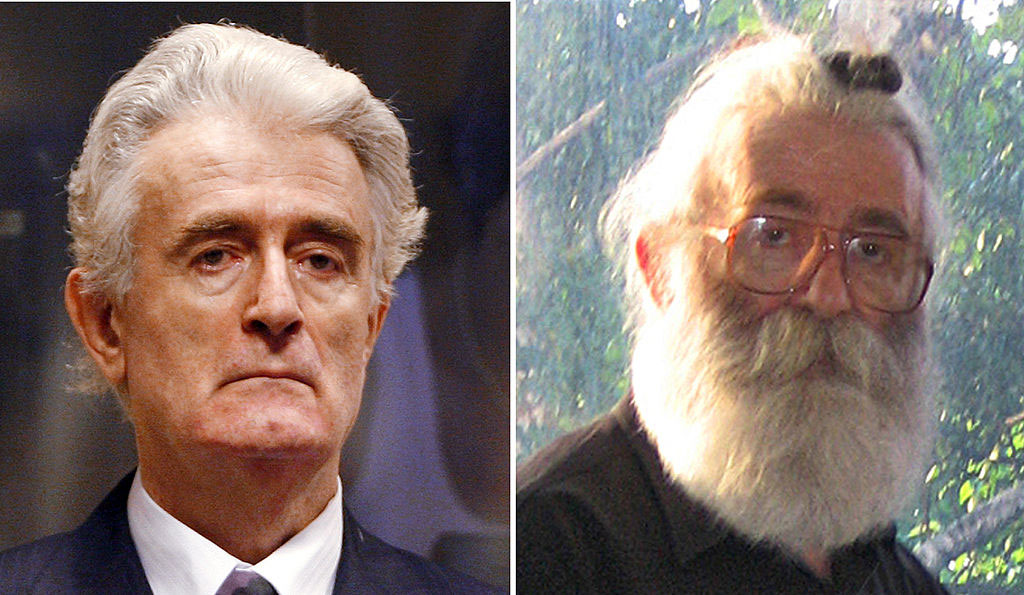

The single most extraordinary story is that of Karadžić himself. At first, NATO forces, which flooded into Bosnia after the peace deal of 1995, were deeply reluctant to arrest him, fearing reprisals against their own men. Eventually, as arrests began and it was clear that international forces would not be threatened, Karadžić fled only later to live in plain sight in the middle of Belgrade: using a stolen identity provided to him by the Serbian State Security Service, he grew a bushy beard and reinvented himself as a mystic healer. His cover was so good that the lady who lived opposite him and who worked for Interpol was utterly unaware who he really was. But when Karadžić was finally tracked down in 2008, he shaved off his beard, and, as though a switch had been flicked, turned back into his former personality.

Advertisement

Borger’s book is specifically about the hunt for those the UN’s tribunal indicted but his conclusion given the disappointment with many of its verdicts, already well before the Karadžić one is eloquent. “Resurgent nationalists in the states of the former Yugoslavia are covering over the truth of what happened with a thick layer of revisionism and denial,” but he adds, trying to be optimistic, “the meticulous record of the tribunal, with its seven million documents, cannot be buried forever. Nor can the demand for justice for humanity’s worst crimes.”

Unfortunately, for all the efforts of the international tribunal to catch figures like Karadžić, many who live in the region may doubt that justice for the wars of the 1990s can ever be fully rendered. To them the recent acquittal of Šešelj and the previous acquittals of prominent Croats, Serbs and Kosovo Albanians have shown how limited the court’s efforts may be in practice. The limits of international accountability, coupled with the apparent weaknesses of domestic courts, is certainly one of the main themes of The Unidentified, a documentary about the Jackals, a Serbian paramilitary unit that operated in Kosovo during the period of the NATO bombing in 1999, made by Marija Ristić and Nemanja Babić, two journalists from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (the only pan-Balkan news organization; it also publishes news in English). I have watched this extraordinary film four times now and it still makes my flesh creep.

The Jackals were led by a local Kosovo Serb criminal called Nebojša Minić, aka Dead. He earned that nickname after showing up to a wake that had been held in his honor when, a few years earlier, he had been reported dead. The story begins with the tale of a truck that was full of exhumed Albanian corpses and that had swerved off the road and fallen into the Danube. It was being driven from Kosovo to Serbia, in a period just after the war when the Serbian authorities were trying to conceal massacres (not just by the Jackals) from incoming NATO troops and hence from the UN’s tribunal. The film goes on to show the extent of the Jackals’ brutal killings with testimony from survivors, who describe how the group rounded up civilian men and boys in a couple of villages and then gunned them down in cold blood.

But what makes The Unidentified remarkable is the participation of Zoran Rašković, one of the killers, who decided to speak about the Jackals’ activities during the war and who testified in court when some of them were later put on trial in Serbia. Rašković says he decided to talk “because, if this seed of hatred remains among us, we’ll get to each others throats again.” After a graphic description of mass murder, he says: “When they were all dead and quiet, I looked up at the minaret and I thought, ‘God, what a beautiful day.’ It was truly a nice, sunny day. And I could not bring myself to look down.” Then someone was sent to get beer, which they drank, and then they went “back home.” It is possible to imagine what might go through someone’s head who has just gunned down dozens of people, but hearing what they actually thought is something else.

Particularly disturbing is the power Dead seems to have had over his men. The paramilitary leader eventually died of AIDS in Argentina but Rašković says unambiguously that, although Dead was “a fanatic with a deranged mind,” if he had still been alive he, Rašković, would not have testified against him. Nine members of the much larger Jackals unit were convicted for these massacres in a Serbian court, but last year that verdict was overturned on appeal and a retrial ordered. An expanded group of twelve are now on trial. Fred Abrahams, of Human Rights Watch, who was among the first to reveal the crimes of the Jackals, in the film describes these men as “sacrificial lambs”: none of the senior military or police involved in crimes in Kosovo have ever been prosecuted in Serbia. (While there have been trials for Kosovo at the UN tribunal, Serbia, like the rest of the region, is supposed to prosecute those further down the chain of command, and its record of success, like that of courts in Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo, has been mixed.)

Advertisement

The extent to which many of the atrocities of the 1990s have simply been ignored, minimized or argued away, except if they were committed by the other side of course, is the subject of A Good Wife, a new feature film directed by Mirjana Karanović, one of Serbia’s most famous actresses. Though it was made for viewers in the countries of the former Yugoslavia and many of its references will be lost outside the region, the film should reach a broader audience. Karanović plays the protagonist, a middle-aged woman named Milena who lives in the town of Pančevo, just outside Belgrade, in a nice house with her successful builder husband. She goes for a routine checkup and her doctor, feeling a problem, orders her to have a mammogram. Fearful of what might be found she delays. Then the doctor says: “Milena, why did you wait so long? The tumor is rather large.” The metaphor is clear: by this time Milena has discovered an old video of her husband and his friends murdering a group of Bosniaks after the fall of Srebrenica.

Now Milena understands the tensions between her husband’s friends, the threats one of them makes against her husband implying he will tell investigators about their “secret,” and his subsequent death which we are led to believe is not simply the result of his being drunk on a motorbike. Everyone in the Balkans will understand that the core of the plot is based on the actual discovery of such a videotape, which shocked the region when it emerged in 2005; and Balkan viewers will also recognize that the lady who appears on TV and whom Milena, in an attempt to deal with this tumor, hands the video to, is supposed to be Nataša Kandić, the famous Serbian human rights activist.

In real life the paramilitary group who was filmed killing the Bosniaks was called the Scorpions, and during the Kosovo war they committed another massacre. A new short film from Kosovo, called Shok (“Friend”), which received a nomination in this year’s Oscars, involves the activities of such a group in the Kosovo war. Set in 1998, when that war began, it is the story of two twelve-year-old boys. Petrit prides himself on being a businessman and is selling cigarette papers to the Serbs. He brings along his friend Oki, but one of the Serbs declares that his nephew does not have a bike and so Oki is forced to hand the bike over. The story races to its tragic conclusion as Petrit’s family is thrown out of their home by the Serb paramilitaries and told that they will die if they look back. But this is no simple tale of goodies and baddies. It is a study of lingering guilt, with the crimes of past returning to haunt the now-adult Petrit when he comes across a bike, or possibly the same bike, years later. Shok is to be shown at the Tribeca film festival later this month.

Another feature film that has gained much attention in the former Yugoslavia is Death in Sarajevo. It takes place on June 28, 2014, on the day the Bosnian capital is commemorating the centenary of the 1914 assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip—the event that sparked off World War I. Directed by Bosnian filmmaker Danis Tanović, who won an Oscar for his 2001 Bosnian war film, No Man’s Land, this is a tragi-comedy set in the city’s once iconic Holiday Inn hotel. On the roof, a TV reporter named Vedrana is doing a live interview with Gavrilo Princip, a descendent of the assassin. He wants to know whom a modern Gavrilo Princip would kill. They argue about the 1990s war, hurling accusations against one another, including a reminder by Princip that innocent Serbs were murdered in Sarajevo during the war, a fact that is generally ignored in Sarajevo and virtually unknown about outside the region. In the middle of the hotel a Frenchman is practicing a dramatic speech for Hotel Europe, a play actually written by Bernard-Henri Lévy, the French philosopher, about the “death of Europe,” while a security man watching him on a hidden camera inside his room sniffs cocaine off his phone as his wife rings to nag him about buying a new couch they can’t afford. Meanwhile Omer, the hotel’s director, prowls the building trying desperately to stave off a strike because staff have not been paid for two months.

Again, it is a film made for a Balkan audience but it provides a revealing sense of how Bosnians remain stuck in the past, their leaders unable to work together for a better future. “We are ridiculous in our stupidity,” laments Vedrana to Princip just before the unexpected climax to the film, in a speech that everyone in the region will identify with. “Instead of helping each other we do everything to make each other’s lives miserable.”

In many respects that could be a motto for the Balkans. Twenty-one years after the end of the wars in Bosnia and Croatia and almost seventeen since the end of the Kosovo war, the region has moved a long away, much of it for the better. Not a day goes by without the region’s leaders or their ministers meeting somewhere to discuss problems, people travel easily now and often don’t even need passports as opposed to identity cards and there is much business between the countries. Yet so much more could be done by Balkan leaders to address the legacies of these brutal conflicts, which have not yet really become history. Sometimes it looks like they are not capable of or interested in doing so and verdicts like the Karadžić one gave Serbian and Bosniak leaders an opportunity to beat nationalist drums again and remind their voters that they had better vote for them or the enemy would one day be back.

The Šešelj verdict produced altogether more complex reactions, especially in Serbia since the president and prime minister were once—before, as Šešelj charges, betraying him—his trusted lieutenants. The prime minister has since renounced the aims of his extreme nationalist past. President Tomislav Nikolić however recently decorated Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court on charges of war crimes and genocide in Darfur.

All this is gloomy, but there is an even gloomier specter haunting the region. In Serbia and Croatia revisionism is in. Last July a court process began in Serbia to rehabilitate Milan Nedić, the Serbian quisling prime minister under the Nazis. In Croatia the new minister of culture is an open admirer of the genocidal Ustasha Independent State of Croatia, which existed during World War II. This year the Croatian Jewish community will boycott the annual ceremony of remembrance which is held at the wartime Jasenovac death camp because it says that the government tolerates revisionism with regards to the Ustasha past. On April 4, a new Croatian documentary about Jasenovac, very much in this spirit, was released to praise from the culture minister.

The failure of the postwar Yugoslav Communist regime to deal with some of this dark history left space for spurious and revisionist claims to grow, once the regime had lost its repressive power. This was one reason why, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, nationalists on all sides were able to blow on the embers of the past in order to mobilize their campaigns to come to power. Books and films about the wars of the 1990s may not be able to change politics but, as the UN’s tribunal winds down its work, they remind us how these tendencies remain very much alive. Dealing with them is necessary, not just for victims and societies today, but for future generations too, lest zombie-like the past returns to poison the future as it has already done before in this part of the world.

Julian Borger’s The Butcher’s Trail is published by Other Press.