Consider the lowly mug shot, artless, indifferent, striving for nothing more than accuracy of likeness for the purpose of criminal identification. Mug shots are the cruelest of posed pictures; punitive, shameful, they make even the young and beautiful look plain. Yet a mug shot is also a kind of formal portrait: you sit (or stand) for it and project whatever the setting and the photographer draw out of you. Flip through the pages of a police booking file and you will see a taxonomy of human expressions, from fear to impotence, haughtiness, fury, grief, and stress. In my own mug shot, taken several years ago after a wrongful arrest, I obligingly present the image my capturers want: puffy and defeated, the pictorial equivalent of a confession of guilt.

In the 1870s, a Parisian policeman named Alphonse Bertillon pioneered the mug shot as part of his “anthropometric” system of criminal identification based on minute physical measurements. For no pay, he spent his free hours examining inmates at La Santé prison, using calipers and rulers to record the length and width of prisoners’ fingers, noses, foreheads, and mouths. Perhaps he was seeking to demonstrate the theory that political “agitators” and other “moral degenerates” tended to have similar physiognomies, a popular fixation in the late 1800s. (Bertillon had no compunctions about violating his own rules of exactitude when it came to imprisoning accused enemies of France. He had no expertise whatsoever as a handwriting specialist, for instance, yet testified as one in 1894 and again in 1899 to help convict Alfred Dreyfus of treason.)

A sampling of Bertillon’s meticulous mug shots, along with about forty crime-related images from American tabloids, police files, security cameras, and photographers both anonymous and widely known, comprise the fascinating exhibition “Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play,” currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

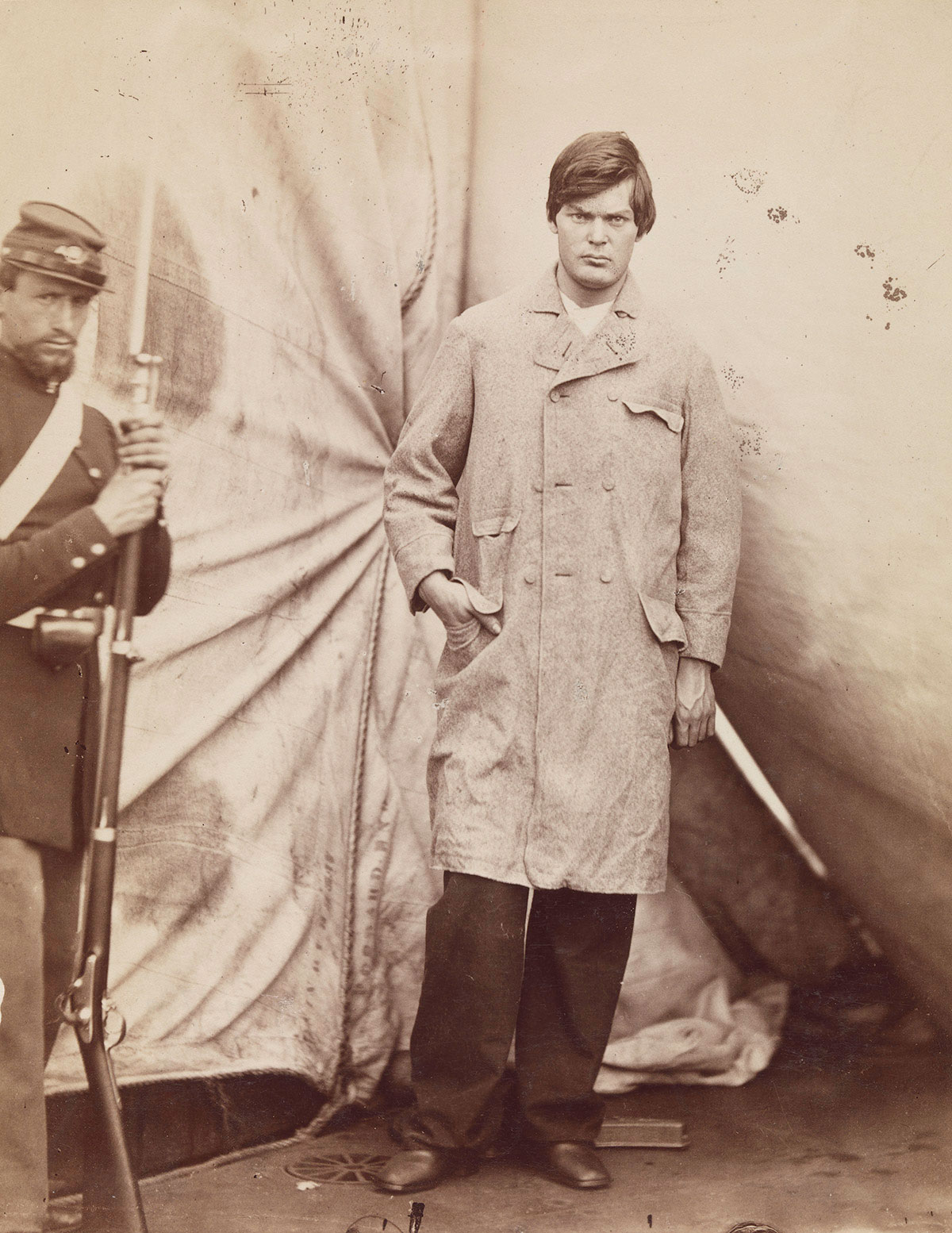

The images on display date back as far as 1865, when Alexander Gardner shot a full-body portrait of Lewis Powell after he had unsuccessfully tried to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward as part of the conspiracy to overthrow (with John Wilkes Booth) President Lincoln’s administration. Powell, young, pleasantly chubby-faced, with rich black hair combed low across his forehead, is wearing a white canvas trench-coat. You sense the importance he places on this photograph, his effort to transmit himself as a captured hero, unrepentant and armored with a kind of calmly fanatical conviction. If it weren’t for the Union soldier guarding him with a bayonet, the picture could pass today for a Ralph Lauren ad.

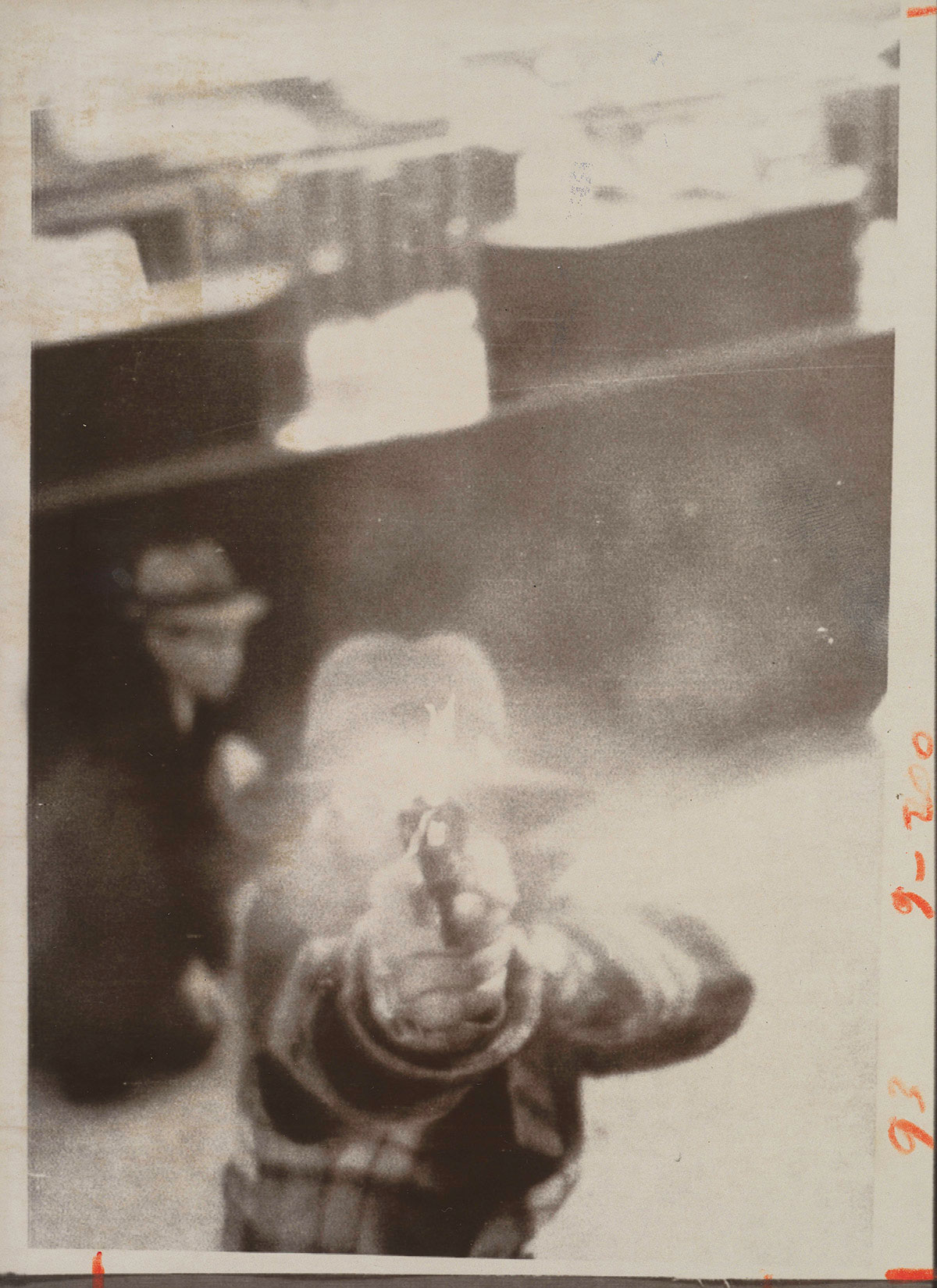

The curators have set up an interesting dialogue between celebrated victims and assassins, on the one hand, and the unknown on the other. A Los Angeles Times photograph of Robert F. Kennedy seconds after he was shot on June 5, 1968, still alert and trying to convey something urgent, it seems, to the person kneeling beside him, provokes a predictable ache as the viewer runs through his knowledge of what followed the assassination and what might have been. The image engages the news gossip in us, the gawker at historical artifacts. By contrast, an anonymous, plebian bank robber, ferociously trying to shoot out a security camera in a burst of smoke and light, invites us to imagine the crime and, by doing so, to insert ourselves into the scene.

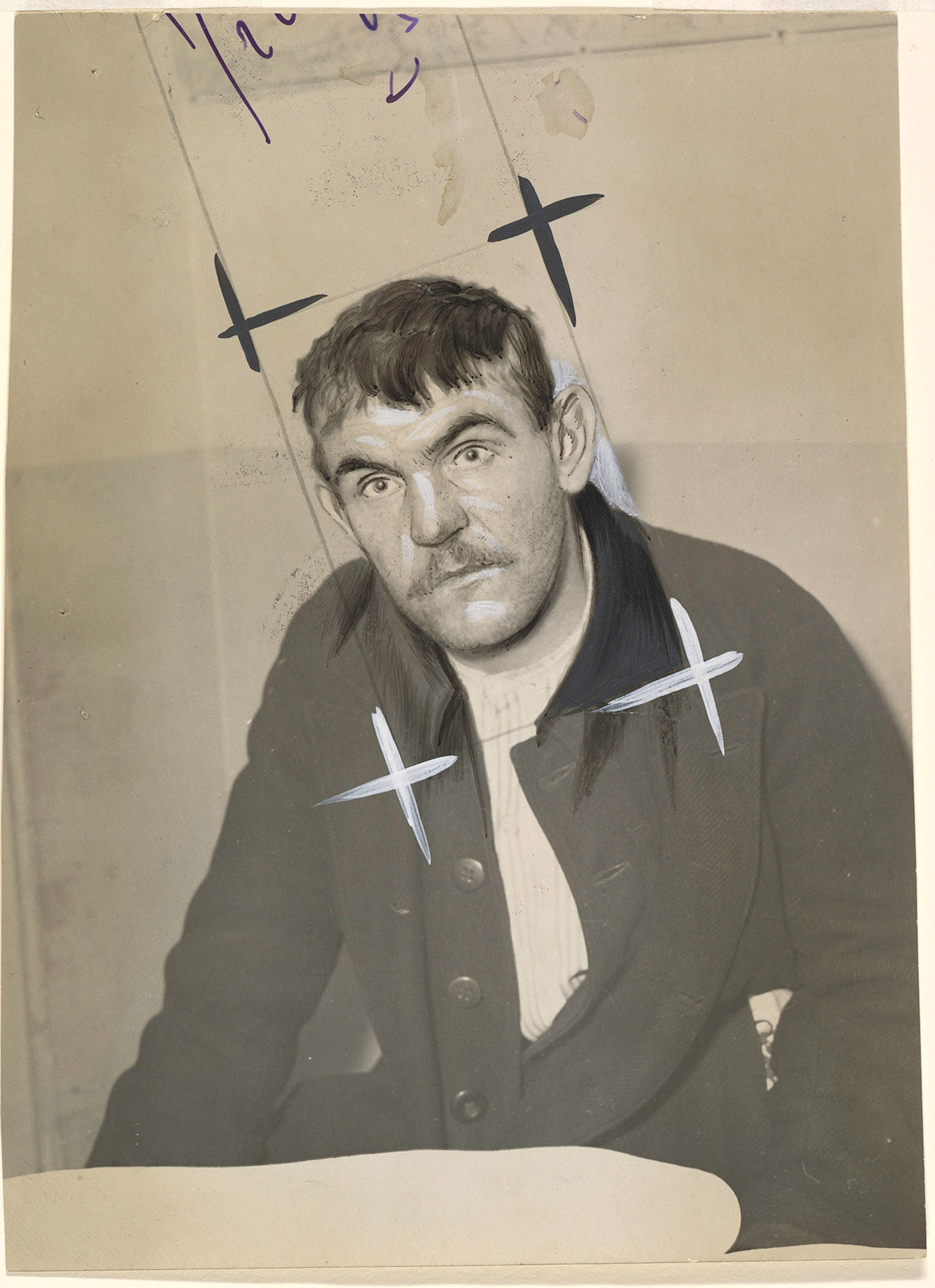

If one measure of a photograph’s power is the extent to which it inspires us to fill in the circumstances around it, then the mug shot of a 1930s Baltimore shoplifter is a small masterpiece of portraitist art. A woman in her late forties, with whitening blonde hair, turns slightly away from the police photographer’s camera with a mix of melancholia and trapped defiance. The flesh around her left eye is badly bruised, a messy black puddle that spills along her cheek and temple. Who slugged her—the department store security guard, the arresting cop, the shopkeeper himself, or an intimate friend? Her lips are thin and subtly crooked, her jawline is just beginning to sag. The life before (and after) the picture rushes in on you in an imagined story of filled-in time. You note the shabbiness that at a quick glance could pass for respectability, the probable alcoholism or drug addiction, the stickpin in her wrinkled cloth hat. You admire what you take to be her underworld intelligence, her survival in the face of obvious hardship and abuse, all the while mulling over the ethical nature of your own coldly scrutinizing eye.

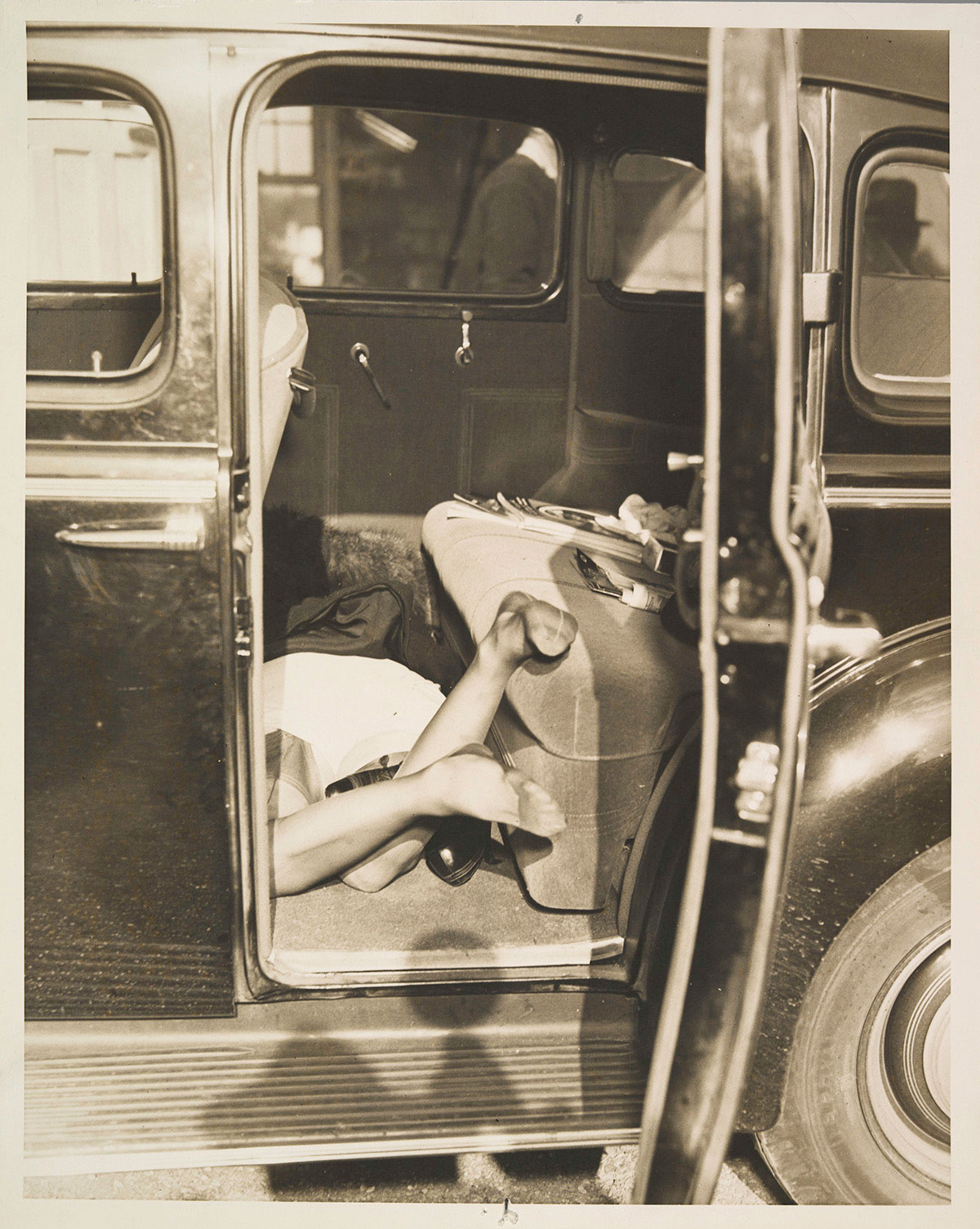

Hanging near a photograph of the stockinged legs of a murdered young woman in the back seat of a car is one of Walker Evans’s sneaky, overcoat-cloaked shots of passengers on New York City’s subway in the Thirties and Forties. “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” Evans called his unwitting subjects. In this example, a smirking, vaguely menacing young man is engrossed in his copy of the Daily News. PAL TELLS HOW GUNGIRL KILLS, reads the headline. An obese woman, obviously not an acquaintance, sits miserably beside him.

Advertisement

Next to the Evans, in turn, hangs Diane Arbus’s on-screen shot of an actress playing a B-movie gun moll that she took from her seat in a theater in 1958. Both photographs are reflections on murder as a species of mass entertainment, especially if the murderer is a woman. Plucked from the running display of ordinary life, they create an event. In the case of tabloid photographers—rushing to a crime scene and capturing what they can on the fly—it’s the event that dictates the picture. By remarking on the pornographic connection between violence and sex that is fed us to sell newspapers and movies, Evans and Arbus offer a different level of news.

In the 1970s, the sexualized outlaw was either a lone wolf existentialist hero (as in Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, his 1979 “true life novel” about the psychopathic killer Gary Gilmore) or a putatively idealistic warrior for political revolution, like Andreas Baader of the Baader-Meinhof gang in West Germany.

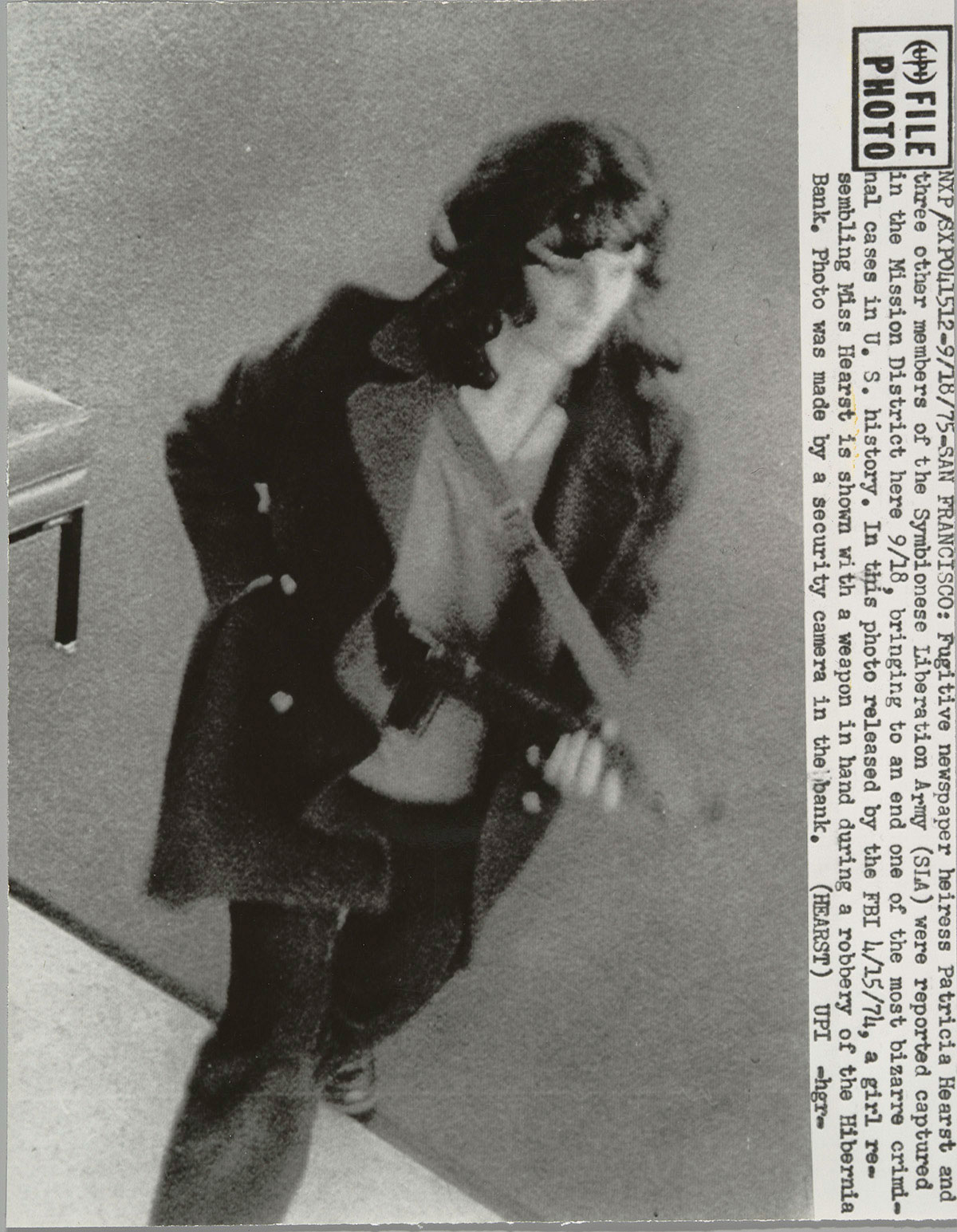

“Photography and Foul Play” includes two potent photographs from 1975, the last and most recent year that the exhibition covers. The first is of Patty Hearst, the nineteen-year-old kidnapped publishing heiress who became, in captivity, an armed Symbionese Liberation Army guerrilla. With her dark feathered hair, her alarmingly fragile thinness, her swung open jacket, and her shoulder-strapped automatic rifle held waist high at a bank heist in San Francisco, she is like a stylized version of a punk rock goddess. The formalizing effect of the framed print on the gallery wall transforms it from the bombarded news and television “evidence” image that it had been into a deliberate and premeditated glamor portrait.

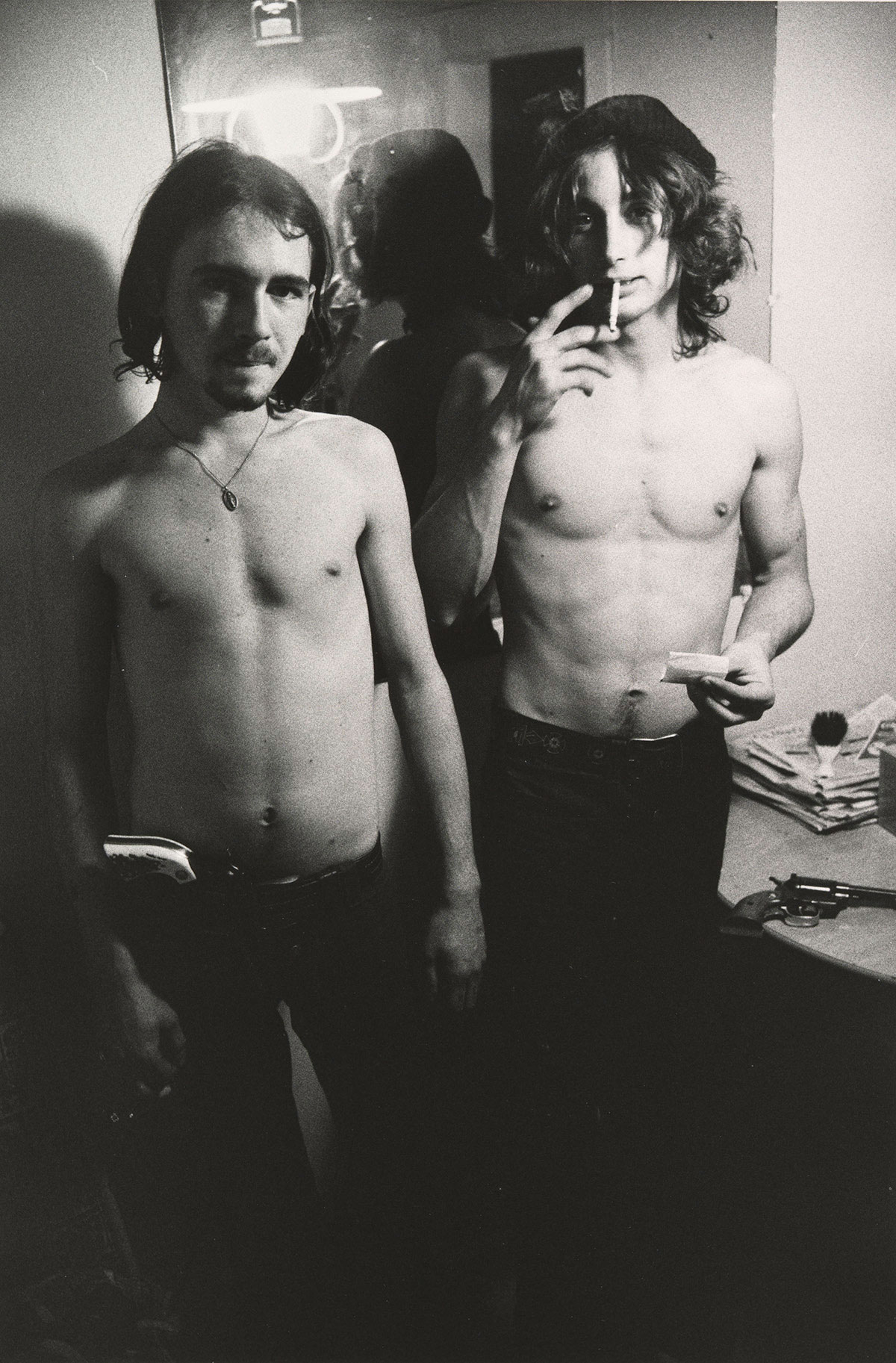

The second is a frankly erotic portrait by Larry Clark of two armed robbers in Oklahoma City. The robbers, maybe eighteen years old and stripped naked to the waist, are posing for Clark in what appears to be a motel room. One has a gun shoved in his jeans, white pearl handle protruding; the other is armed with a Mick Jagger haircut and pout, lit cigarette dangling from his lips, his revolver on a table beside him. To Clark, they are stars, and you can feel the tug of his admiration for them, his desire to be like them, his kinship and awe.

Richard Avedon is represented by his 1960 portrait of Dick Hickock, the Kansas murderer who was one of the subjects of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. In his typical style, Avedon presents a large-scale investigation of Hickock’s face: the black greased pompadour combed just so, the slightly fleshy nose, the disturbingly engaging eyes, all of it ever so slightly skewed by the impression of Hickock’s inscrutable lopsided grievance. (Hickock had suffered a brain injury in an automobile accident when he was nineteen.) As with Gardner’s 1865 portrait of Lewis Powell (who was also executed by hanging for his crime), you sense how seriously Hickock takes being photographed, his wish to give something of himself, to influence, if not control, the emanations of his image and how he is being portrayed.

“He’s hot!” said one of three teenage girls at the exhibition the day I was there. Giggling, they took turns standing for cell phone pictures next to Hickock’s face, as if showing off their latest romantic interest.

“Crime Stories: Photography and Foul Play” is showing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 31.