The National Portrait Gallery is a curious museum, as we seem to go there more often to see people than to admire paintings: it works as a visual shorthand for British history, full of gaggles of schoolchildren doing the Tudors. But one of its current shows, “Russia and the Arts: The Age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky,” plunges us into a different history. Over the past few years the NPG has built a reputation for curating unexpected small exhibitions alongside its larger blockbusters: this remarkable show of Russian portraits is one of those. And it is one that should not be missed.

The exhibition is an exchange with the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow—both galleries are celebrating their 160th anniversaries. The NPG has sent to Russia “From Elizabeth to Victoria”—which includes portraits of writers from Shakespeare and Milton to Byron and Burns—while the Tretyakov has lent a galaxy of thirty portraits of writers, musicians, composers, actors, and patrons. Twenty-three of these have never been seen in Britain before, and they conjure up a tortured yet astoundingly vibrant cultural life covering fifty years, from the last tsars to the revolution and beyond.

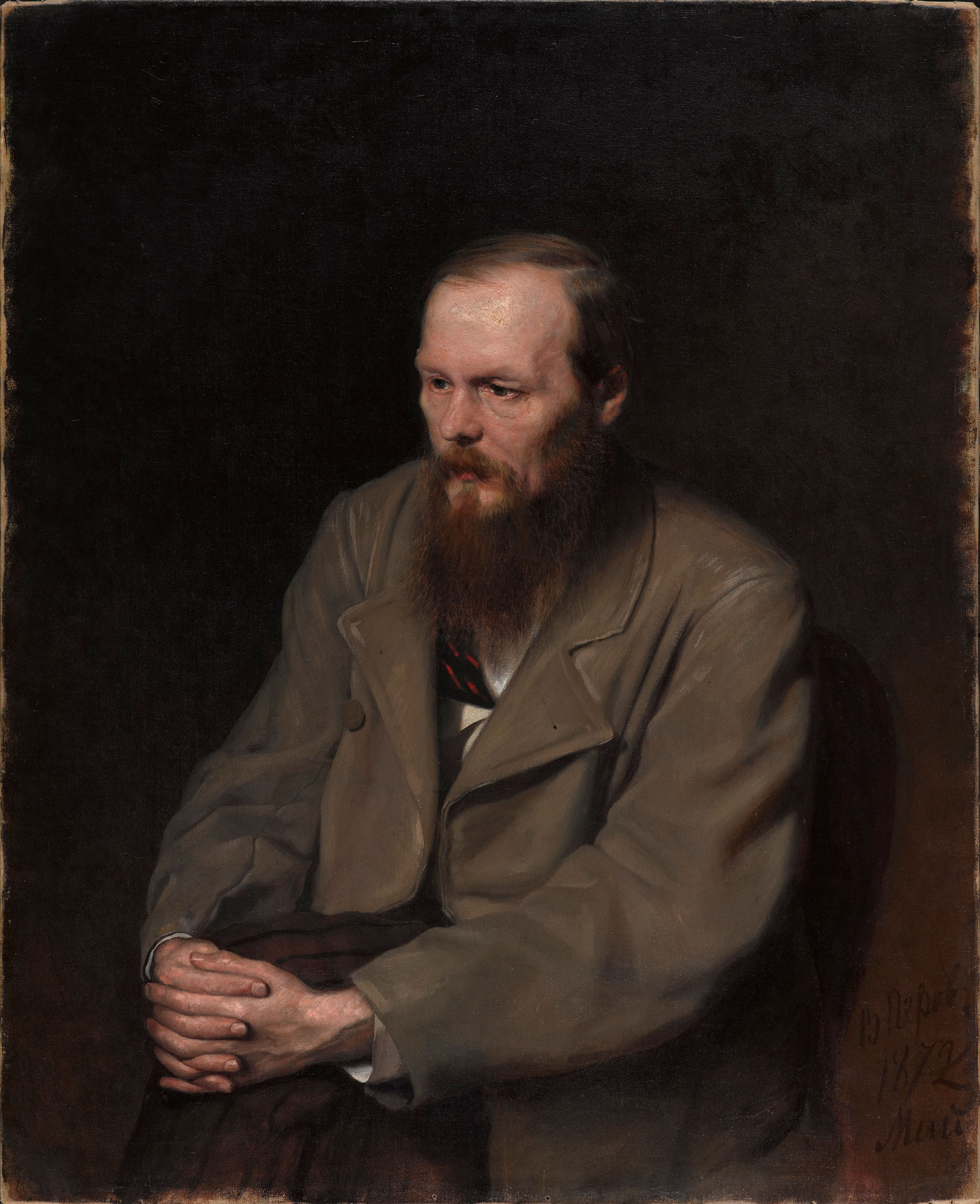

I found these serious, unsmiling portraits astonishing. They feel governed by the belief that a portrait—like an intense conversation between artist and sitter—can bring us closer to its subject than any new-fangled photograph could do. And sometimes it’s true. With Vasily Perov’s 1872 portrait, suddenly here we are, face to face with Dostoevsky: he crouches low on the canvas, his thin frame huddled in a great brown overcoat, his gaze withdrawn and distant, his fingers tightly laced. As the light shines on his boyish forehead, his wispy hair and beard and withdrawn gaze, the sense of exhaustion yet inner focus is haunting. He had been living in hardship for thirty years, ever since his arrest as a twenty-eight-year-old in 1849 for being a member of the radical Petrashevsky Circle, an event that had doomed him to Siberian labor camp and forced army service, to damaged health and wounded spirits. Yet he had continued writing, his will unbroken.

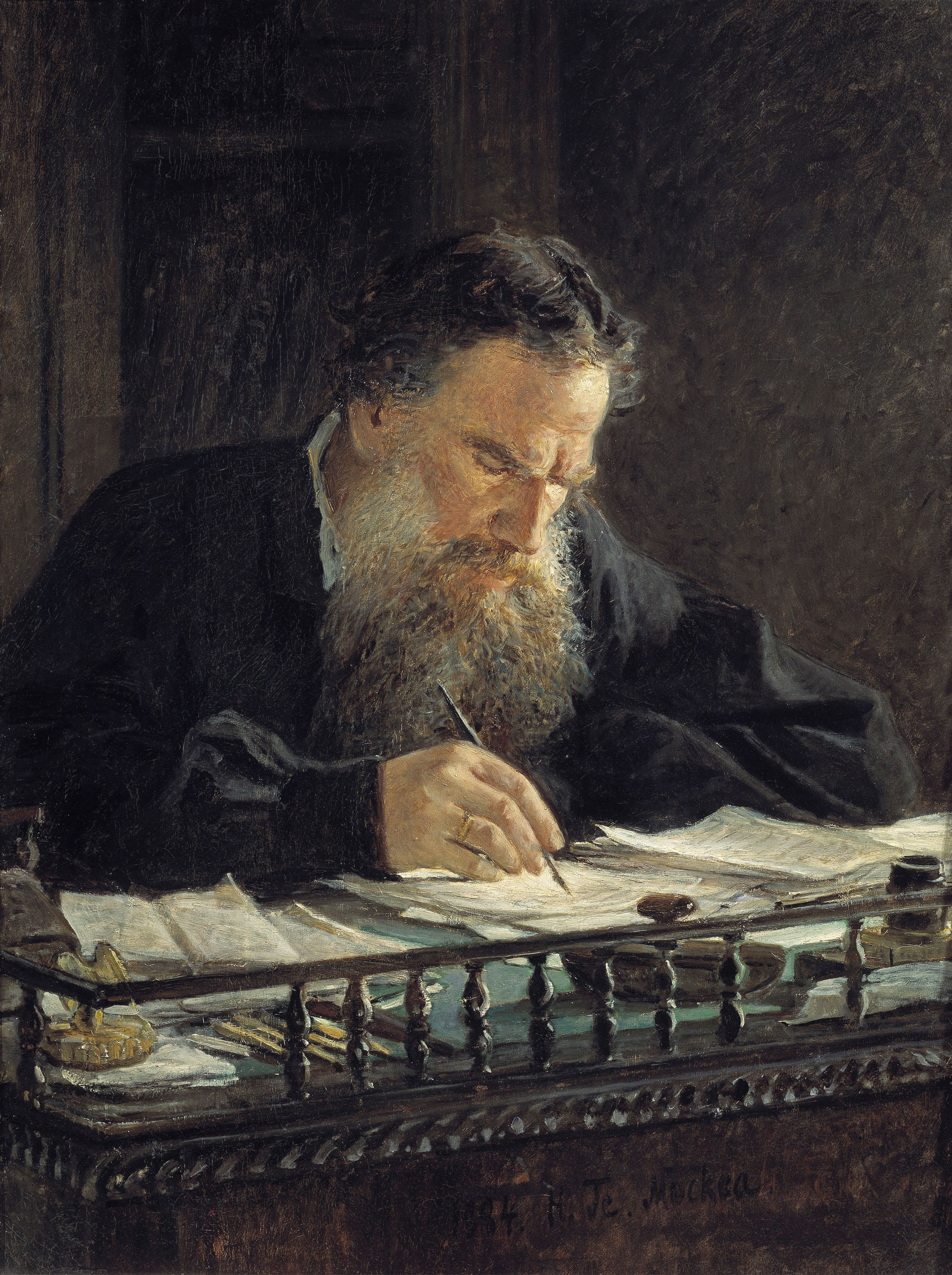

It’s moving to turn from this to Nikolai Ge’s 1884 painting of Tolstoy crouched over his desk; or to Ilya Repin’s huge canvas of an aging, glowering, huge-nosed, white-haired Turgenev, painted in France in 1874, so different from the thoughtful Turgenev of Nadar’s relaxed, genial photograph three years later, which is included in the fine exhibition catalog. Turgenev’s relationship with Repin was fraught, and his flinty gaze still knocks us back, as if we, the viewers, are as guilty as the intrusive artist. This suggested how much we judge portraits by preconceptions. And made me ask, again, in what sense is a portrait “true”?

On the opposite wall, in equally formal pose, is Chekov. The painter Iosif Braz caught him at a turning point in 1898, when a Moscow revival of The Seagull—which had been denounced at its premiere in St. Petersburg —was loudly acclaimed, launching his career as a playwright. Uncle Vanya would be staged the next year. Yet Braz’s Chekov, neat in his wing collar and dark grey suit, his pince-nez on his nose, sits back as if he judges us and can see through our skin, while determined to reveal nothing of himself.

The pictures of composers are equally strong and strange: Repin’s driven Anton Rubinstein, with folded arms and mane of dark hair; Nikolai Kuznetsov’s Tchaikovsky, taut, strained, hand clenched, imprisoned in his suit; Valentin Serov’s Rimsky-Korsakov amid an organized chaos of scores and books. Among these hangs the most powerful portrait of all, Repin’s animated, tousled, red-nosed yet clear-eyed painting of Mussorgsky in 1881, just before his death.

Repin, with his sensitive, intuitive rapport with all his sitters, is the hero of this show for me. The son of a military settler in the Ukraine, his background was far from grand. He made his reputation as a student in St. Petersburg with paintings like Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870-1873), showing the men harnessed to drag the boat: although commissioned by a member of the imperial family this was a vivid attack on the brutality of labor and, beyond that, on social injustice as a whole. After a Russian Academy scholarship in France (where he painted Turgenev), he returned determined to paint in a distinctively “Russian” style.

There is humor in Repin’s portraits as well as empathy and understanding. Great warmth, for example, in his sexy, self-possessed pianist Sophie Menter, Liszt’s brilliant protégé; and a keen wit in his classic swagger-portrait of the salonnière Baroness Varvara Ikskul von Hildenbandt with her wickedly pointed hat and veil. At once bold and restrained, this is painted with such enjoyment that we can almost feel the weight of the locket chain round her arm and touch the gathers of her scarlet blouse and sweeping skirt.

Advertisement

“The Age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky” is fascinating for other reasons than the sitters. The first is its very existence. This is only a fraction of the collection amassed by the textile tycoon Pavel Tretyakov (1832-1898), from the 1860s to his death, which later became the core of the State Tretyakov Gallery. The portraits, conceived as a separate group, formed a museum within a museum: their subjects were heroes and heroines, embodying the genius of Mother Russia. A crucial influence was Tretyakov’s enduring friendship with Repin, who not only painted for him, but advised him on other artists. Repin’s painting of Tretyakov in front of his collection—a memory after his death, based on an earlier portrait—shows a diffident, reserved man, whose passion was poured into his family and his love of literature, theatre, music and art.

And what a passion that was. Something of his obsession, and, perhaps, his steely determination not to lose a star for his collection, can be sensed in the history of Repin’s great Mussorgsky portrait. Mussorgsky had had reached a peak of fame in 1874 with his opera Boris Godunov and his piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition, only to tumble into drinking bouts in St. Petersburg taverns, often lasting for days. In 1881 he was hospitalized with chronic alcoholism, and when Treytakov heard that his condition was serious he sent Repin dashing down to paint him. Treytakov was right: when Repin arrived for his final sitting, Mussorgsky was dead, aged only forty-two. The catalog quotes Repin’s record of their brief time together, talking over the assassination of Alexander II: during the breaks, Repin said, “we read a mass of newspapers, all on one and the same terrible subject.” He thought Mussorgsky “a natural talent,” a medieval warrior with the appearance of a Black Sea sailor; he was not averse to playing the fool.” Repin took no fee, donating it instead for a memorial.

Because Tretyakov was concerned about fine painting as well as important sitters, the exhibition is also a journey through changing artistic fashions and an introduction to artists we might otherwise not know. It moves from the realism of Vasily Perov, Nikolai Ge, and Repin himself to the impressionist-influenced work of Valentin Serov, including a stately Sargent-like painting of the actress Maria Shermolova. In a different mode, in 1910 Serov painted the collector of modern French art Ivan Morosov, using a flat “Russian realist” style to make Morozov stand out against a colorful Matisse. On this journey through styles, we encounter, too, the pioneering—almost proto-Cubist—expressionism of Mikhail Vrubel. Though much admired, this works less well in this show: one drawback of the NPG’s spaces is that in the relatively small rooms Vrubel’s fragmented, mosaic-like technique disintegrates into disturbingly scattered blocks.

And at the end there is a different, yet familiar, problem: If we care about the people, does the quality of the painting matter? Here are two writers, the poet Nikolai Gumilev, executed for counter-revolutionary activity in 1921, and his wife Anna Akhmatova, both painted by Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaia, in a Munch-like Symbolist style. These are not great paintings. Yet the Akhmatova portrait undoubtedly “succeeds,” for we know who she is. Here she sits, a proud heroic profile against a glowing sky, depicted in 1914 on the brink of a lifetime of surveillance and persecution that could never drown her poetry or silence her brave opposition to the horrors she saw.

“Russian and the Arts: The Age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky,” is on view at the National Portrait Gallery in London through June 26.