In the preface to her posthumously published memoirs, It Was All Quite Different, written in 1960, the last year of her life, Viennese-born writer Vicki Baum begins with a reckoning of sorts:

You can live down any number of failures, but you can’t live down a great success. For thirty years I’ve been a walking example of this truism. People are apt to forgive and forget a flop because they care little about things that aren’t in the papers or on television, and a book that fails dies silently enough. But a success, moth-eaten as it may be, will pop up among old movies or as a hideous musical or in a new film version, or in a Japanese, a Hebrew, a Hindu translation—and there you are.

The success to which Baum is referring is her international best seller Grand Hotel. In the novel, Baum brought her readers into a complex, multi-perspectival world—in this case a luxurious, pulsating, yet vaguely tragic first-class hotel—in which they can eavesdrop on the conversations, and on the lives, of the finely observed people that she presents. Readers became so attached to the characters that when the novel was initially serialized in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, whose circulation at the time topped two million, they wrote letters of protest after a certain unnamed character (no spoilers here) gets killed off late in the story. Originally published as Menschen im Hotel in Berlin in 1929, the book was quickly adapted to the stage, co-written by Baum, where it opened in January 1930 to rave reviews and an extended run at the Theater am Nollendorfplatz under the direction of Max Reinhardt and his star pupil Gustaf Gründgens (who played the leather-clad gangster boss in Fritz Lang’s M the following year).

When Grand Hotel was published in the United Kingdom in 1930, it earned a new round of impassioned accolades from both critics (“brilliant” and “especially poignant to the present day”) and the public. After an English-language stage adaptation made a major splash on Broadway, Doubleday released the American edition in early February 1931. It spent several weeks at the top of the Publishers Weekly bestseller list and sold 95,000 copies in the first six months. Baum soon relocated to Hollywood, where she assisted in adapting her story to the screen at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer; the credit sequence of the film features her prominent byline beneath the title. In 1932, she attended the glitzy premiere in Times Square, escorted by none other than Noël Coward. Directed by Edmund Goulding and starring Greta Garbo, the Barrymore brothers, and Joan Crawford, the film earned the studio the Oscar for Best Picture that year.

For such a spectacularly successful novel, Grand Hotel had a rather humble beginning. Baum, who was born in Vienna in 1888, the only child of an upper-middle-class Jewish couple, first conceived of the story as a young girl, jotting down sketches in her notebook while on a family trip (she had published her first story in a Viennese satirical magazine called Die Muskete at the age of fourteen). Originally trained as a classical harpist at Vienna’s Academy of Music, the teenaged Baum was invited by her aunt and uncle to perform at a public concert held in their hometown of Lundenburg (today Břeclav), an Austro-Hungarian hamlet near the Moravian border. During her three-day visit, the big-city girl got her first taste of life in the provinces, observing the different characters in her midst. One of the members of the chorus that accompanied Baum’s performance, a trembling little man with “an enormous Nietzsche mustache” and a browbeating wife known as Fräulein Sauerkatz, provided the outline for Grand Hotel’s Otto Kringelein, the ailing, downtrodden bookkeeper who arrives in Berlin on a mission to squeeze as much as he can out of his final days of life.

Years later, after Baum landed a full-time job as a writer and editor at Ullstein Verlag, one of the largest publishers in Europe in the 1920s, newspaper headlines about a hotel-room tussle between a cat burglar and an out-of-town businessman caught her attention. They planted the seeds of the dashing but morally compromised Baron Gaigern and the callous, greedy General Manager Preysing, both of whom found their places, right next to Kringelein, in the old notebook that she still carried with her. Around this time, Baum went to see the ballet in Berlin and came home with an image of Elisaveta Alexandrovna Grusinskaya seared into her mind. Baum had witnessed onstage, as she later recounted, the “fading” Russian prima ballerina Anna Pavlova, leaving the theater “with an infinitely melancholy impression, a half-empty house, an audience that, under the influence of [the German modern dance choreographer] Mary Wigman, had grown tired of ballet, and yet there was the luminous glow of a great, a born, dancer.” Soon she had assembled her dramatis personae, including the shell-shocked Doctor Otternschlag, the dutiful porter Mr. Senf, the saucy stenographer Flämmchen, and the others. (“I am a slow thinker,” Baum once said of herself, “but a fast writer.”) As she commented many years after the book’s publication, “the wooden puppets grew flesh, arteries, veins, nerves. I pulled them together in a hotel where their ways might cross.”

Advertisement

Perhaps another reason for the novel’s instant success was the way in which it spoke to the anxieties of Weimar society—and of the world at large—about modern life. The characters reflect that ongoing tug-of-war between the new and the old. Doctor Otternschlag stands as one of the tens of thousands of war cripples and psychologically scarred soldiers that returned home after the Great War—so memorably captured in the evocative cycle of war paintings completed by Otto Dix earlier that same decade. Generally numb to the world, missing half of his face (“A souvenir from Flanders”), and often in a morphine-induced slumber, he lingers at the reception desk looking for messages and new reasons to continue his tortured existence. “He always set a distance between himself and others,” writes Baum early on, “though he was not aware of it . . . he was dismally alone, empty, cut off from life.” When not searching in vain for errant communiqués, he’s overheard muttering his refrain: “Always the same. Nothing happens.”

The supreme diva Madame Grusinskaya, too, is a formerly grand, now decaying figure from the past—much like the misplaced portraits of Bismarck hanging above the hotel beds—her fan base seemingly dwindling by the day. And like Otternschlag, she self-medicates with Veronal to inure herself to the pains of the world, summed up in her woeful mantra: “Oh, the cruel public. Cruel Berlin. Cruel loneliness.” When Kringelein goes to see her dance on the fifth of her nightly performances in Berlin, the theater is nearly empty. “Leave me alone,” she begs her French assistant Suzette (anticipating Garbo’s most famous line in the film adaptation, “I want to be alone”), “I am not well. I can’t go on again.”

Snapping back to life—or, rather, discovering it for the first time—the narrative counterbalance to Otternschlag and Grusinskaya is Kringelein, who finds himself in a “mysterious state of intoxication,” which he can recall having experienced only once before, when he played hooky from school as a young boy in Fredersdorf. Having left behind his former life of “very restricted circumstances” for good, Kringelein can now catch a late show at one of Berlin’s picture palaces or go window-shopping along the Kaiserdamm; he can drink rounds of the “Louisiana flip” cocktail du jour at the hotel bar, dance to jazz for the first time, go to a boxing match and for an adrenaline-charged drive through the city’s boulevards with Baron Gaigern. He no longer needs to report to his wife or to his former boss. He eventually learns a sad truth, indeed: “Only with money can you begin to be a decent human being.”

As for Baron Gaigern, he’s a handsome thief with a heart of gold, a faux-aristocratic playboy with expensive taste and no money of his own. “There was a smell of lavender and expensive cigarettes,” comments the omniscient narrator the moment Gaigern is introduced, “immediately followed by a man whose appearance was so striking that many heads turned to look at him. He was unusually tall and extremely well dressed, and his step was as elastic as a cat’s or a tennis champion’s. He wore a dark blue trench coat over his dinner jacket. This was scarcely correct perhaps, but it gave an attractively negligent air to his appearance.” He charms all whom he encounters, including Kringelein, whose total makeover he orchestrates while instructing him in joie de vivre. Yet over and over, given the chance to steal, Gaigern’s outsize superego, or maybe his overgrown heart, gets in the way. After sneaking in to Grusinskaya’s room to snatch her pearls, he peers out from behind the curtains and sees the dancer fully disrobed. Captivated by her beauty, he falls in love and instantly scraps his larcenous plans. Similarly, after Kringelein collects his winnings at the gambling table and falls unconscious from his excesses, Gaigern cannot bring himself to prey on his new friend.

Baum was certainly not the only Weimar-era writer or intellectual preoccupied with the hidden social life of the hotel nor, as Wes Anderson’s 2014 cinematic homage Grand Budapest Hotel shows, was it a preoccupation confined strictly to that era. The film critic and sociologist Siegfried Kracauer, who published an influential study on the cultural dispositions and social habits among white-collar workers the same year as Baum’s novel, wrote a short piece in the mid-1920s titled “Die Hotelhalle” (“The Hotel Lobby”). In it, he quotes from a popular Norwegian crime novel Death Enters the Hotel: “Once again it is confirmed that a large hotel is a world unto itself and that this world is like the rest of the large world. The guests here roam about in their light-hearted, careless summer existence without suspecting anything of the strange mysteries circulating among them.”

Advertisement

Indeed, beneath the layers of frothy dialogue, Baum’s novel contains a core of intense sociological and even philosophical reflections, articulated poignantly by its narrator and embodied by its characters.

The experiences people have in a large hotel do not constitute entire human destinies, full and completed. They are fragments merely, scraps, pieces. The people behind its doors may be unimportant or remarkable individuals. People on the way up or people on the way down the ladder of life. Prosperity and disaster may be separated by no more than the thickness of a wall. The revolving door turns, and what happens between arrival and departure is not an integral whole…. And anyone who attempts to give an account of what he has seen…runs the risk of balancing precariously on a tight rope between falsehood and truth.

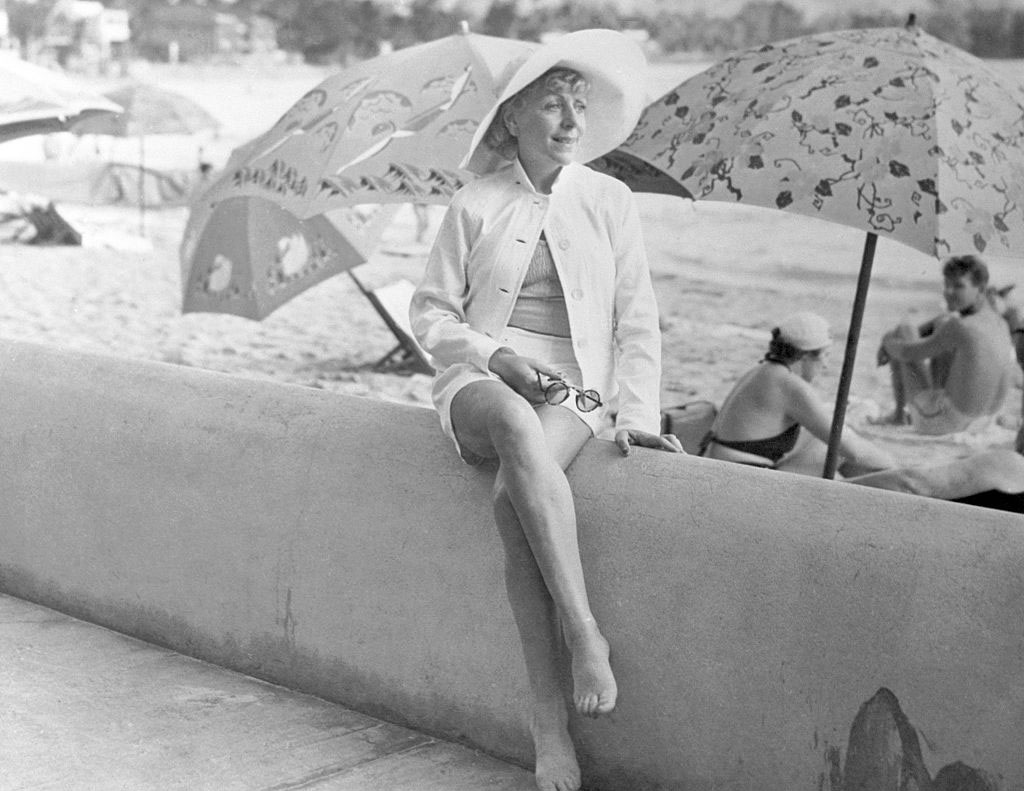

Soon after working on the Hollywood adaptation of her novel, while the Nazis began their ascent to power, Baum took up residence in Los Angeles, the city she called home until her death in 1960. She went on to write another dozen novels, including Hotel Shanghai (1939) and Hotel Berlin ’43 (1943), yet none was as successful, none as deeply woven into the fabric of twentieth-century fiction, as her Weimar-era best seller. To see Grand Hotel reissued in the country in which Baum was ultimately most anchored, and where in 1938 she became a naturalized citizen, some eighty-five years after its first release, is to see a long-deserved tribute to its author. Although the staggering success of the novel may have proved daunting—“It made me feel like a cat with a tin can tied to its tail,” she once quipped—it now has the chance of a new life in a new century.

Adapted from Noah Isenberg’s introduction to a new edition of Vicki Baum’s Grand Hotel, translated by Basil Creighton with Margot Bettauer Dembo, which will be published by New York Review Books on June 7.