What can a photograph tell us about the interior life of its subject? During photography’s early days in the mid-nineteenth century, the photographic portrait was often expected to convey a certain neutrality. Long exposure times required stillness, while the prevalent study of physiognomy, in which facial features were believed to reveal character traits, made some think that visible emotion would undermine the accuracy of a portrait’s static likeness. But with technological advances in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some photographers began experimenting with pathognomic portraits—photographs that were meant to capture an individual’s particular expressions, with the implication that emotional expression might better convey the character, personality, or essence of a subject.

The photographs of Marcel Sternberger (1899-1956)—the focus of historian Jacob Loewentheil’s new book, The Psychological Portrait: Marcel Sternberger’s Revelations in Photography—exemplify this approach. Sternberger, whose career spanned the 1930s to the 1950s, was a leading portrait photographer of his generation. “One might argue that there is hardly a more recognizable portraitist in the history of photography,” writes Phillip Prodger, head of the photography department at London’s National Portrait Gallery, in the book’s foreword.

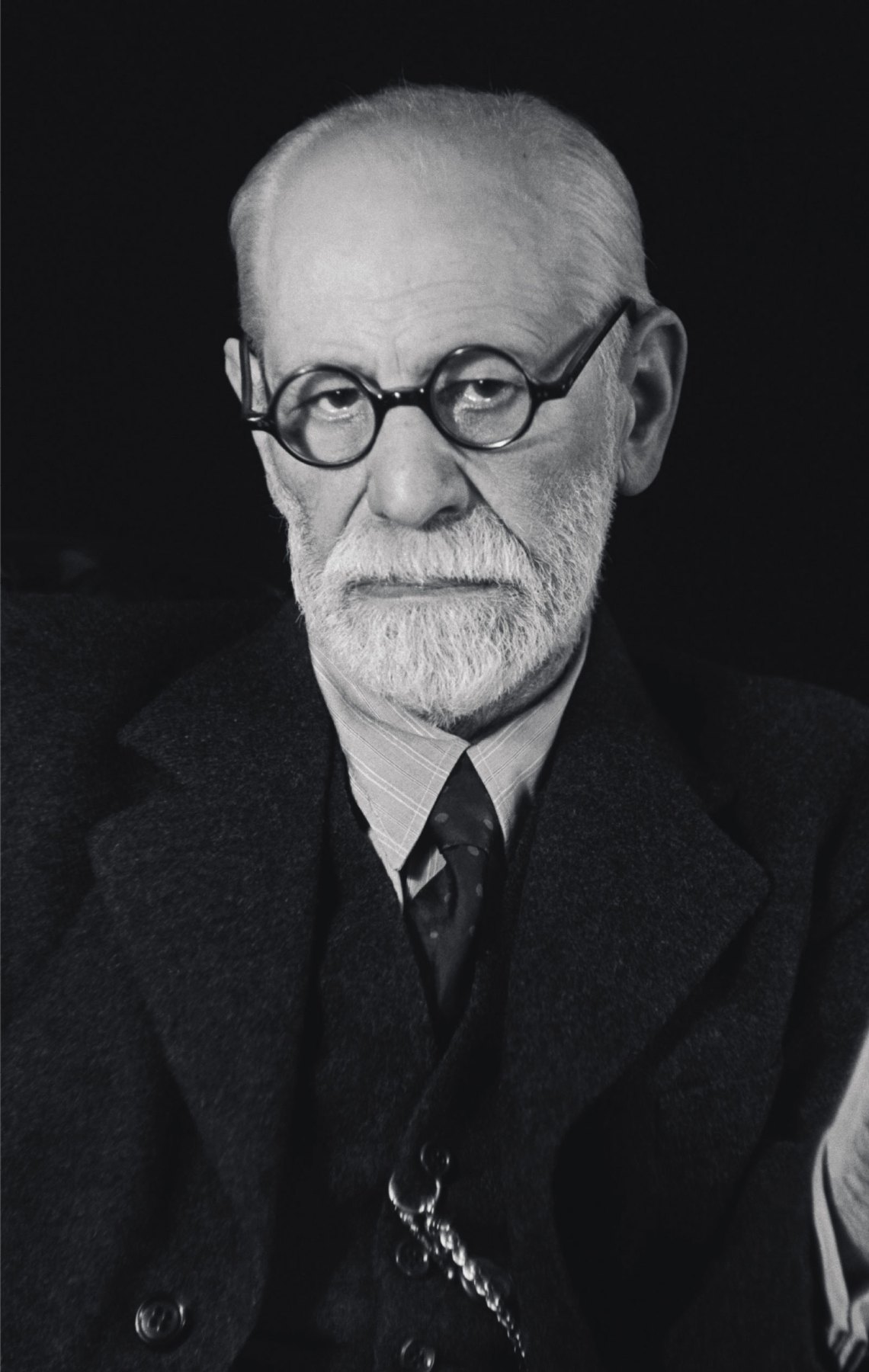

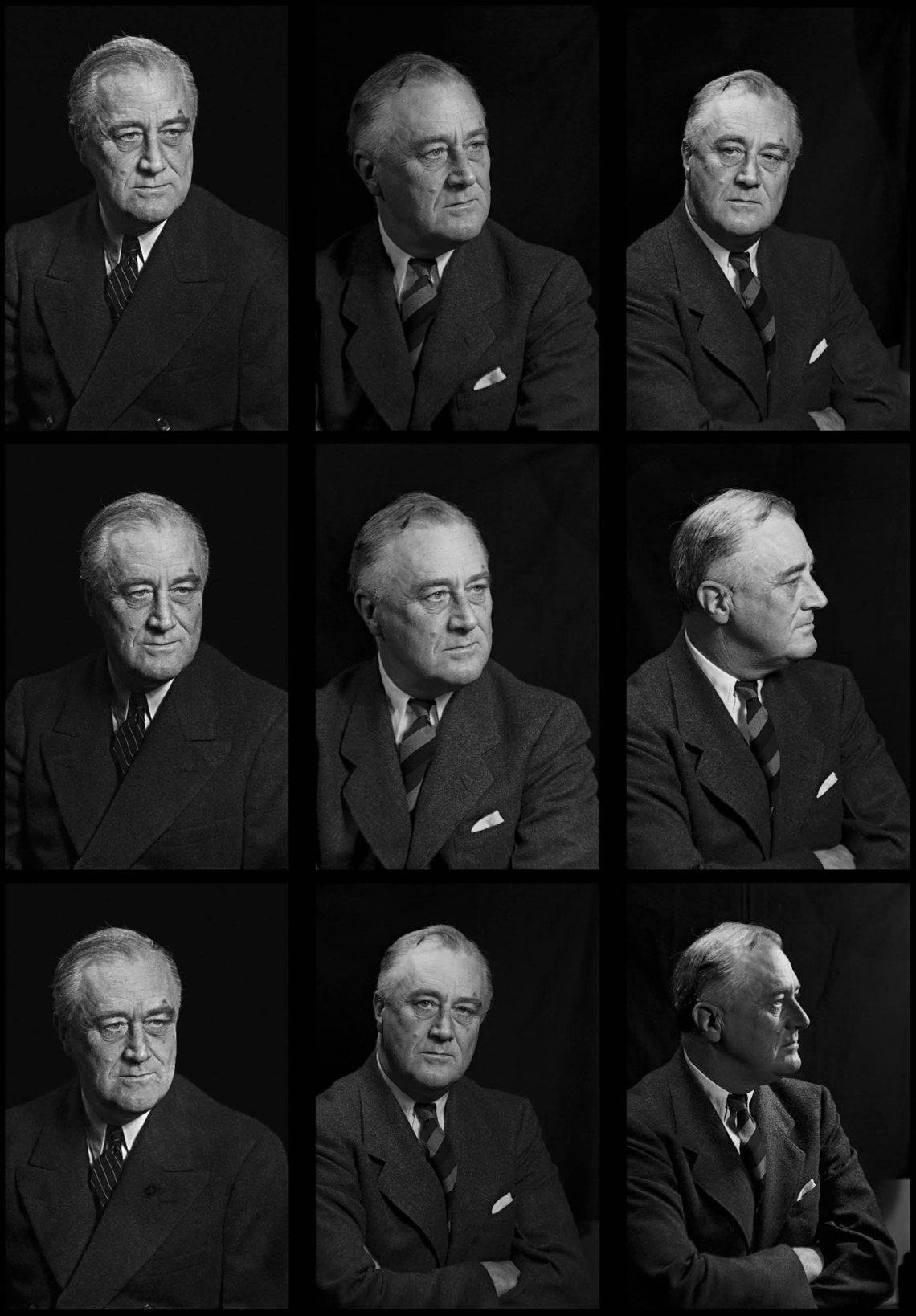

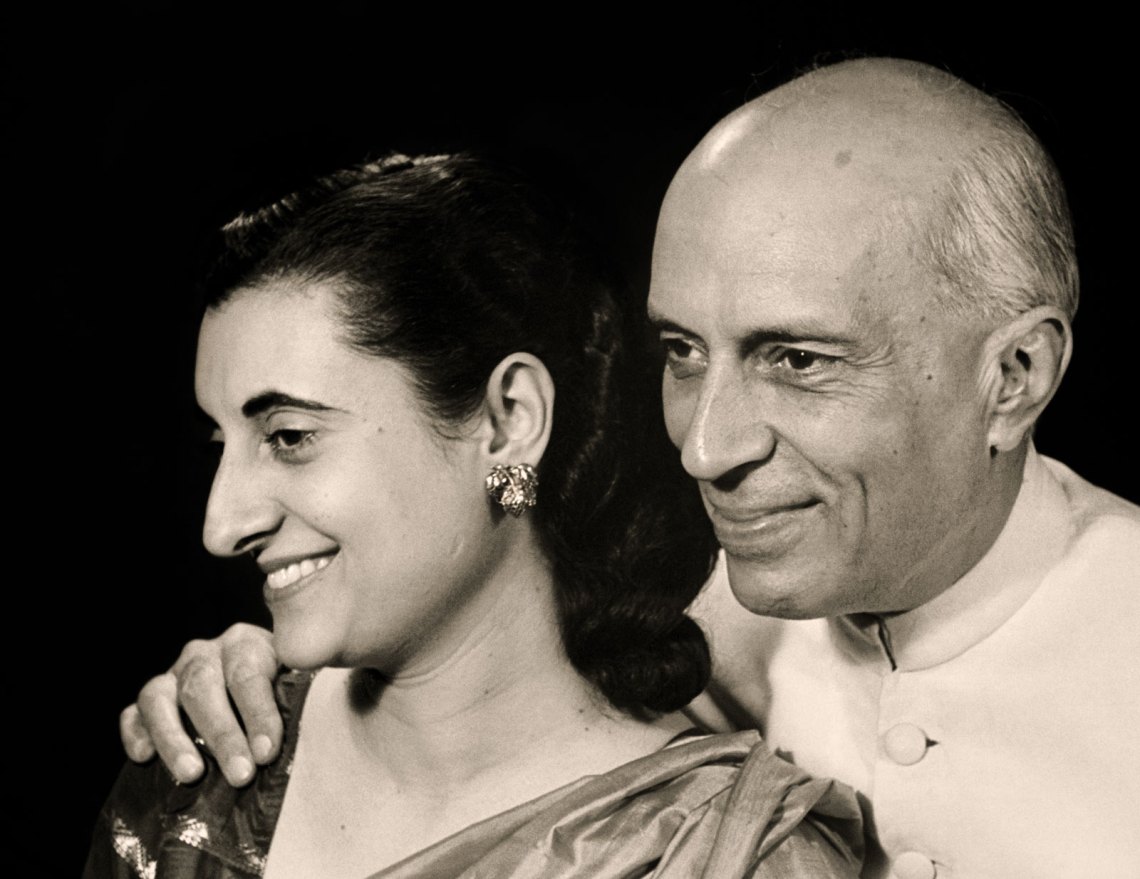

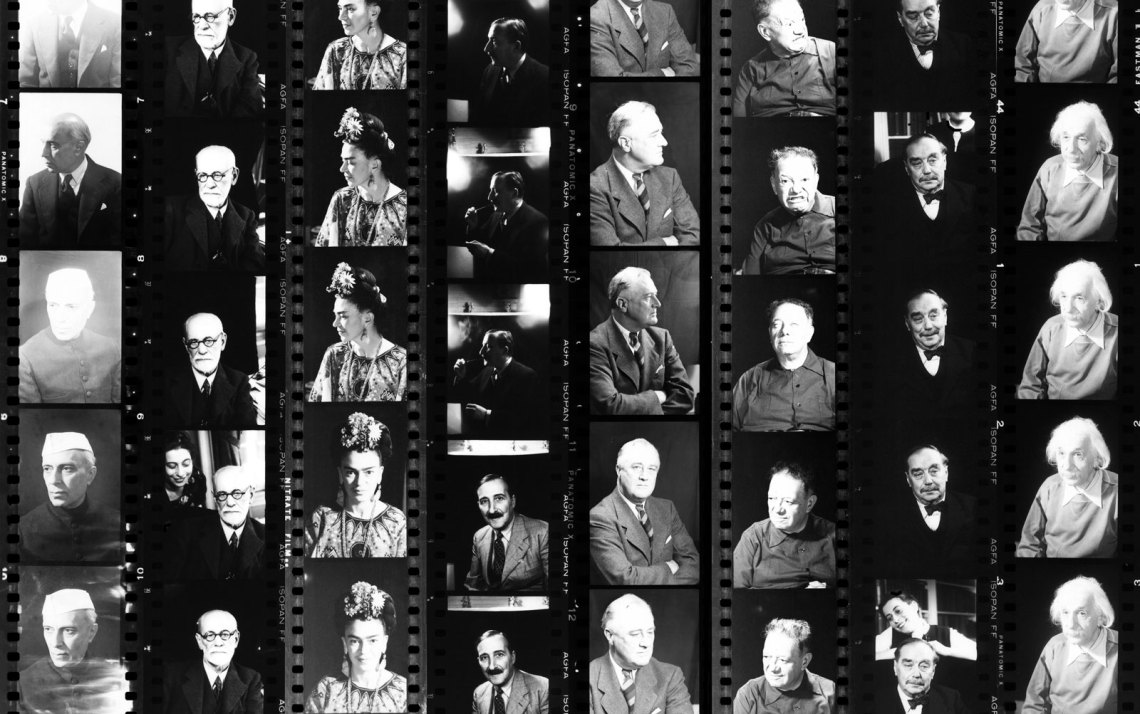

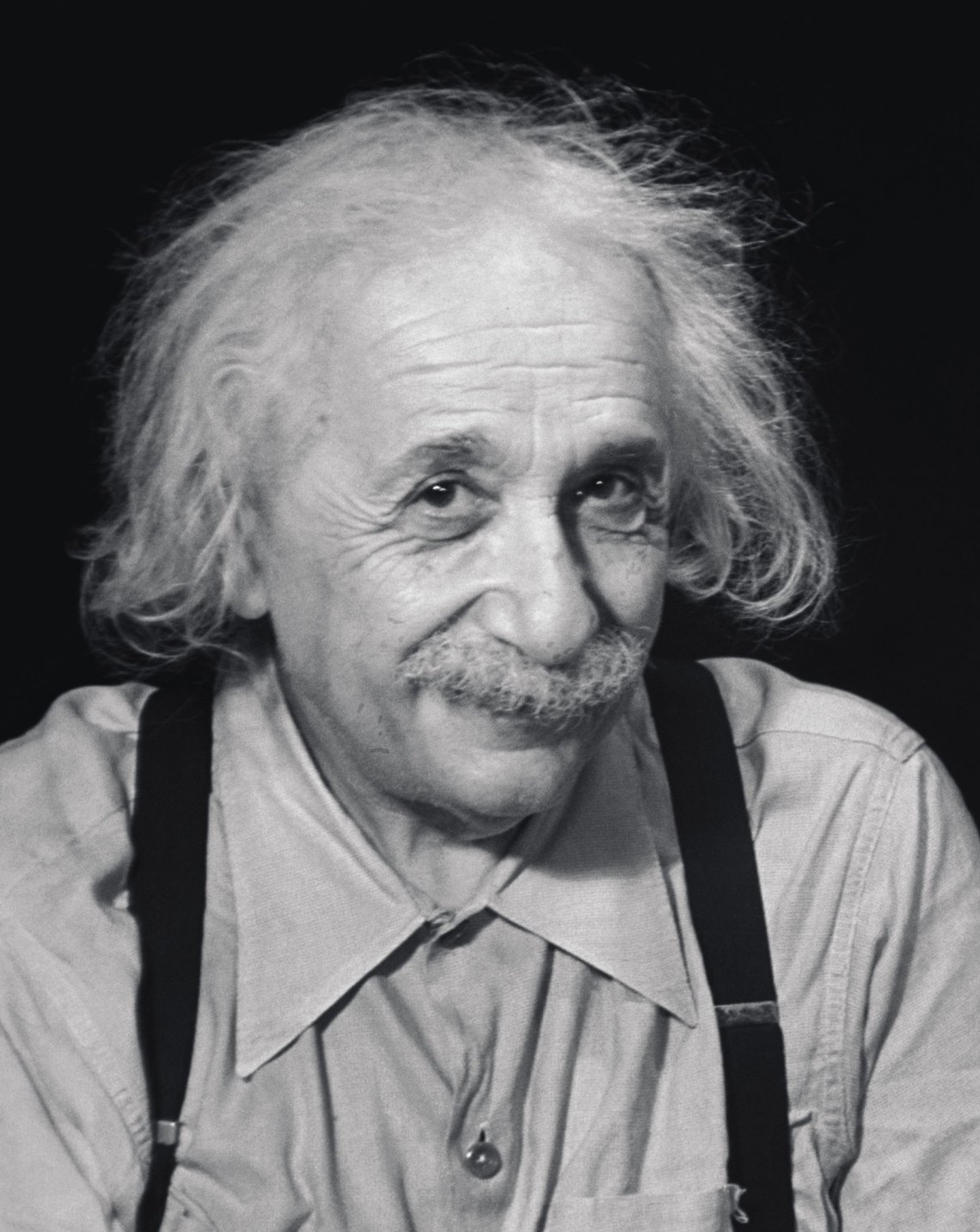

Though Sternberger has since faded into obscurity, many of his portraits have not. It was the golden age of photojournalism, but his photographs—including of some of the most celebrated political leaders, artists, and intellectuals of the time—were meant not only to document, but to tease out and capture his subjects’ personalities: FDR looking elegant and determined (his image on the dime was produced from one of Sternberger’s shots); a humorless Freud who, Loewentheil writes, “could easily have discerned the psychology taking place on both sides of the lens, [still] even he was not immune to its effects”; Frida Kahlo smiling beatifically, a flower crown fixed to her hair and mystery behind her eyes; Albert Einstein looking impish (of his portrait, he wrote, “It seems quite amazing to me that you could present this subject so appetizingly”). Sternberger’s portraits revealed intimate, rarely-observed characteristics of these well-known figures, who were accustomed to managing their public personae; his image of father and daughter Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi sitting together, for example, shows them emanating mutual love and respect.

The invention of photography the century before had been followed by the fledgling field of psychology, sparking a new interest in emotional expression. Starting in the 1840s, neurologist and physiologist Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne used painless electrical probes and a camera to stimulate and document movement in the facial muscles, which led to more complex questions about how facial expressions related to a person’s character and behavior. When Sternberger was working, huge developments in psychology—he went on to photograph Duchenne’s star student’s protégé, Sigmund Freud—had converged with the handheld camera’s increasing democratization of photography. The psychological portrait, Sternberger’s visionary theory, embodied his acute awareness of the complex relations required of a portrait session.

After fleeing his native Hungary in the 1930s, when attacks on Jewish citizens escalated, Sternberger taught Hebrew and Jewish history in Prague, then became a professional journalist writing for Austrian, French, and Hungarian publications. His wife, Ilse, gave Sternberger his first Leica as a wedding gift in 1933. He came to public attention after photographing the Belgian royal family in 1935, and with their help he moved his family to London, then to New York, when World War II began.

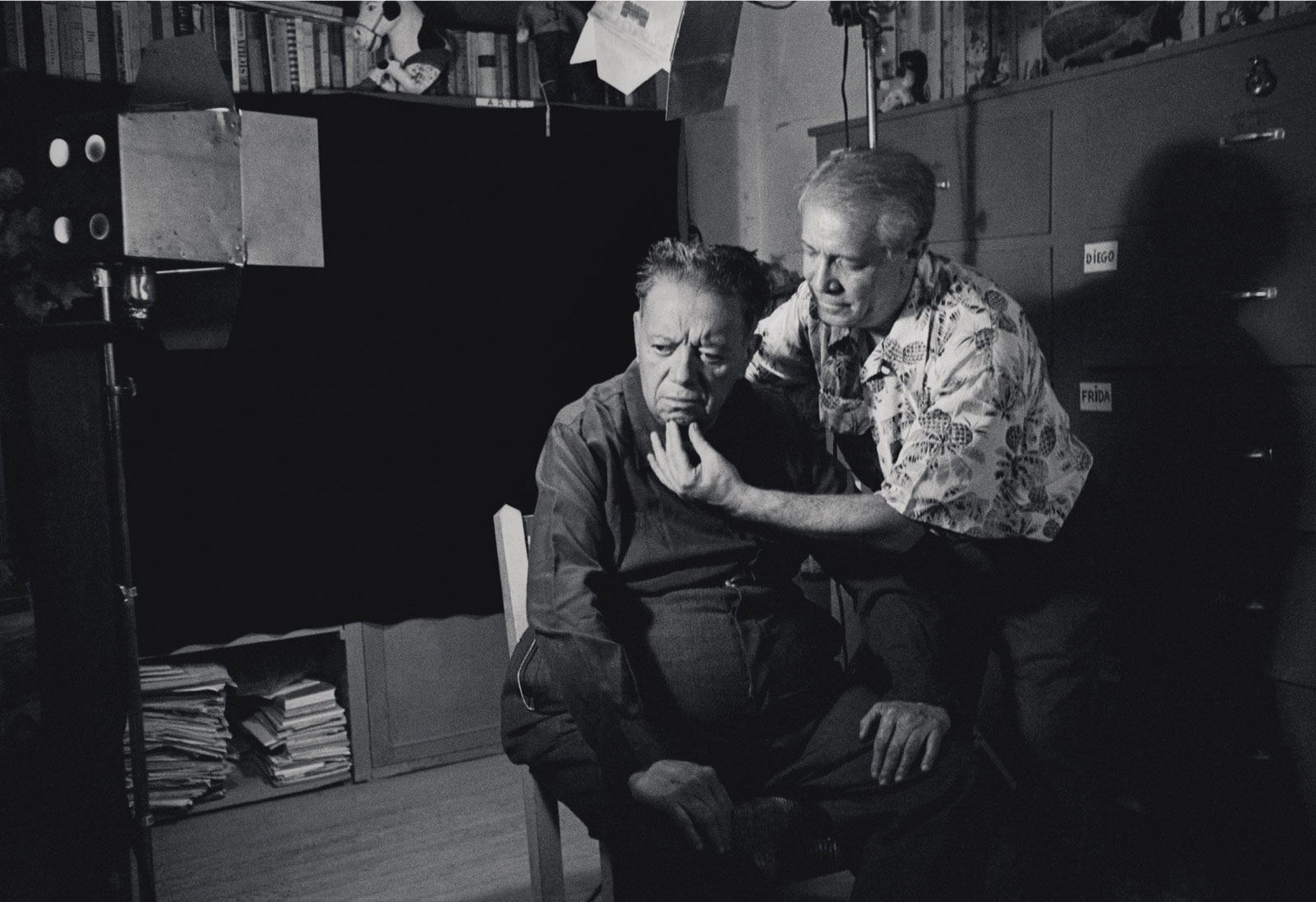

He went on to lecture at NYU on the psychological portrait, while becoming, with Ilse’s support and collaboration, one of the most important portrait photographers in America. Ilse had studied photography in Berlin, and provided both technical and artistic assistance, holding the black cloth backdrop behind Sternberger’s subjects as well as engaging in conversation with them, “often provoke[ing] joyful interactions among the participants,” writes Loewentheil. There are a handful of photographs in The Psychological Portrait in which Ilse, between formal shots, has lowered the backdrop cloth and appears smiling behind Nehru, Freud, or Shaw.

Sternberger always conversed with his sitter before photographing, using “tactful, diplomatic questions” to get closer to the subject, and applying psychological principles like adapting to a sitter’s behavior and alleviating any perceived discomfort to create a photograph that captured the subject’s inner state. “During the short span,” he said, “I must discover all the qualities which his family and friends have learned to value over a period of years.” He explained his techniques in a manuscript, on which Loewentheil’s book is based, that was still unpublished when he was killed unexpectedly in a car accident in 1956, at the height of his career. In this text, which included diagrams illustrating various techniques and instructions (“eyes with sagging pouches are best photographed with a bright indirect or harmoniously diffused light”), Sternberger identified distinct categories of insecurity—Camera Consciousness, The Studio Braggart—and suggested methods of assuaging each, to avoid interference with the shot. He warned portraitists not to exaggerate lighting or background, nor to use props, special effects, or stiff posing, for “the critical camera does not tolerate excess.”

Genuine, spontaneous, authentic, natural, informal, true—these are some of the words, Loewentheil suggests, that Sternberger might have use to describe his portraits. Though perhaps expressed, in some cases, in antiquated terminology, many of Sternberger’s psychological insights—for example, taking into consideration the trauma of dislocation some of his subjects had undergone during World War II—have been supported by modern research, Loewentheil writes. One might rightly be skeptical about how much can be fathomed about an interior psyche from the evidence of facial expression—and whether, in any case, such insight might be conveyed by a single photograph. Today with our smartphones, we are so immersed in images—and selfies—that it seems doubtful that any one image, among so many, might convey some absolute statement of a person’s inner being. And yet it’s tempting to believe that some personal essence might be captured. Of a portrait made by Sternberger, Diego Rivera said it was “the first time I have seen the real me…behind the mask.”

Jacob Loewentheil’s The Psychological Portrait: Marcel Sternberger’s Revelations in Photography is published by Rizzoli.