New York City’s High Line of 2003-2013—a bold rethinking of the urban park that quickly became a beloved civic institution—was such a departure from business-as-usual land development in America’s financial capital that it seemed a rare fluke. However, even the most thoughtfully conceived public amenity can be undermined by its own success, as proved by the high-style, high-priced condominium towers that increasingly threaten to turn that verdant elevated promenade into a claustrophobic corridor.

Now, a new and in some respects even more extraordinary landscape on Governors Island in New York Harbor is adding another major enrichment to the metropolis. The July 19 opening of the Hills, a ten-acre park on the island’s southern end that has been eight years in the making, brings to a triumphant conclusion the $350-million campaign to turn the disused military installation into a grand green space unlike any other in the city. Something of a topographic miracle has been wrought on this 172-acre islet in Upper New York Bay, less than half a mile from the tip of Lower Manhattan and a quarter mile from Brooklyn.

Unlike many cities, whose islands are exclusive residential enclaves—such as the Île Saint-Louis in Paris, Miami’s Fisher Island, and Seattle’s Vashon Island—outlying land masses in New York City’s waterways have long been consigned to society’s most marginalized members: the indigent, the criminal, the insane, the contagious, and the abandoned dead. For centuries the armed forces have claimed a number of the harbor’s strategically placed coastal rocks and reefs to protect against naval attack, the rationale behind Castle Williams on Governors Island, which was erected between 1807 and 1811 in anticipation of the coming war with Britain.

In peacetime, urban military emplacements tend to be forgotten by the general public. Only when land values escalate do covetous eyes turn toward such enticing areas. In the 1990s the US government began to offload redundant military real estate as a cost-cutting measure, and Governors Island was a particularly tempting morsel on which developers were ready to pounce. According to The New York Times, a 1998 study commissioned by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani “concluded that [a] high-class gambling casino would provide the most revenue of any development option being considered.”

Later schemes were advanced—including for a marina and for movie production studios—but also came to naught. In 2003 the property was sold jointly to the state and city of New York for $1. This was during the troubled reconstruction of Ground Zero, which had devolved into an embarrassing quagmire as competing national, state, municipal, and private interests vied for control. Eager to circumvent further jurisdictional struggles, Mayor Michael Bloomberg eventually wrested control of Governors Island from the state, and the metamorphosis proceeded unimpeded.

During his twelve-year tenure Bloomberg catered excessively to big developers and the very rich, and showed comparatively little concern for those on the opposite end of the economic spectrum. But he did get certain things right. His administration reclaimed hundreds of miles of the city’s despoiled shoreline for recreational purposes, supported the High Line, encouraged the use of bicycles, and saved Governors Island from commercial exploitation— Bloomberg’s proudest achievements.

Fortunately, restrictions imposed under the federal handover forbid several uses for the island, including gambling, permanent housing, and cars, save for service vehicles. (Hotels are permitted, though none has yet been planned.) And thanks to the water that surrounds it, the enclave will likely be spared opportunistic encroachments of the sort that now impinge on the High Line.

Although the Trust for Governors Island will rent space to meet the park’s operating expenses—tenants thus far include the New York Harbor School (a public secondary academy specializing in marine studies) and a day spa now under construction—care has been taken to maintain the site’s low-key atmosphere. And adding to the bucolic spirit of the place, in 2014 the Trust, in partnership with GrowNYC, also opened an 8,000-square-foot “urban farm,” to promote and teach sustainable agriculture.

Governors Island is shaped like an ice cream cone; the rounded northern portion reveals its natural configuration, while the triangular southern segment was created in the early 1900s by the US Corps of Engineers with landfill from the excavation of the Lexington Avenue subway line. The tree-shaded historic part of the property to the north—which includes such delights as the circular sandstone Castle Williams, a phalanx of veranda-fronted officers’ residences, and the neo-colonial Liggett Hall barracks designed by McKim, Mead & White—was landmarked in 1996. (An informative guide to this urban oasis is provided by Kevin C. Fitzpatrick’s newly released Governors Island: Adventure and History in New York Harbor, which traces the site’s development from the city’s first settlement to the present day.)

Advertisement

A turning point came in 2006, when the estimable Leslie Koch was named president and CEO of the Trust for Governors Island, the body set up by Bloomberg to oversee the reworking of Governors Island, the cost of which has been borne by both the city and state of New York.The meagerly landscaped newer section, in particular, was blighted by a cluster of grim high-rise military billets that resembled a low-income housing project and cried out for radical change. Soon after her appointment, the energetic and imaginative Koch led a design competition for this area.

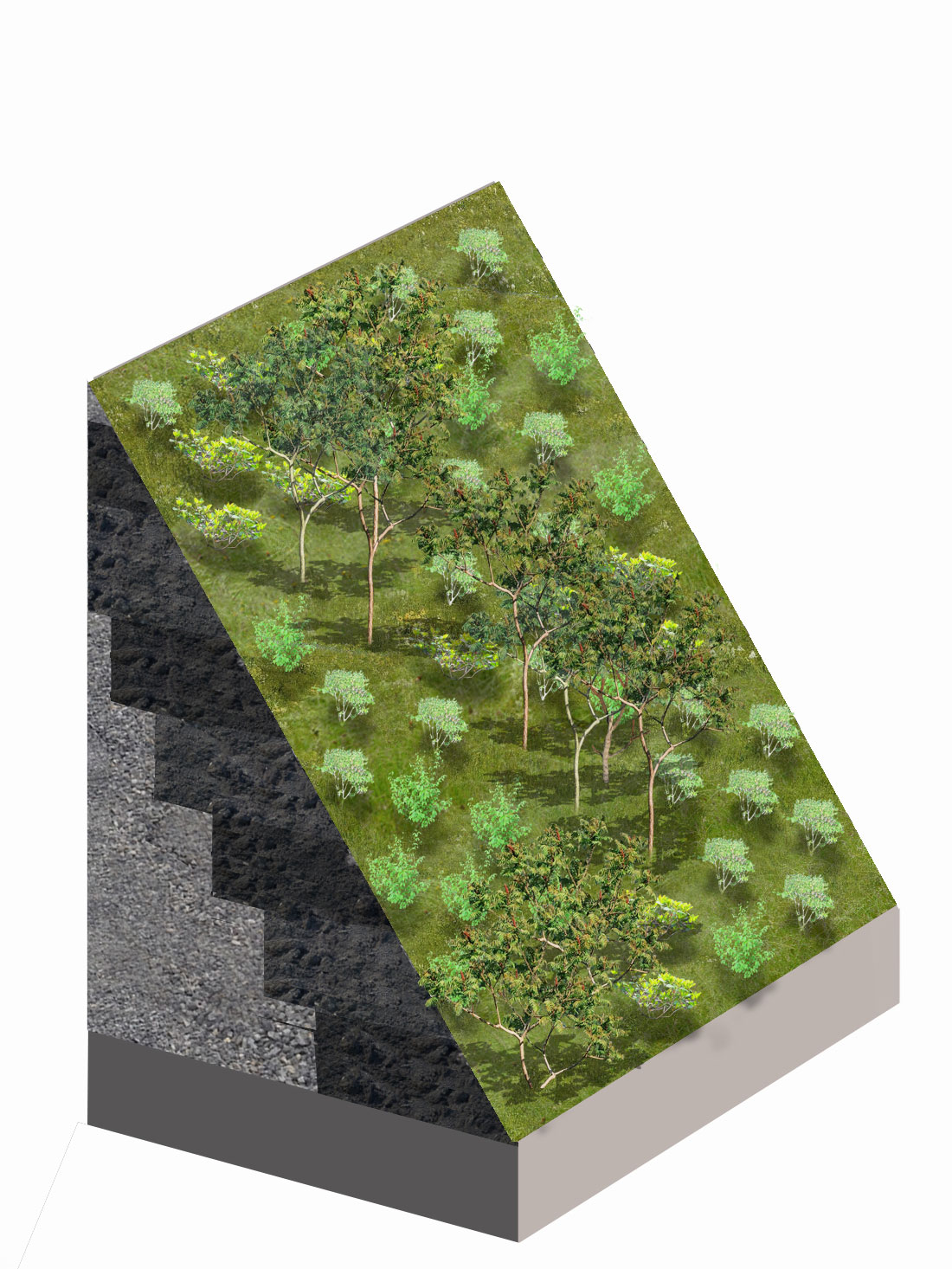

The $70-million job went to West 8, a Rotterdam-based firm whose principal, Adriaan Geuze, proposed reshaping this pancake-flat terrain into graduated hills that would seem the result of geological happenstance. Geuze devised a remarkably naturalistic series of artificial mounds that, once their plantings fully grow in, will feel as if they’d been there forever. More than eight hundred trees in different stages of maturity—thirty-two species including birch, hickory, pine, sassafras, tulip poplar, and eight varieties of oak—are complemented by 40,000 shrubs of nineteen kinds, among them blueberry, ceanothus, inkberry, sumac, and summersweet, all intelligently and artfully arranged by the New York landscape architects Mathews Nielsen to preserve open sight lines toward surrounding landmarks.

This quartet of gently shaped outcroppings was constructed in part with debris from the postwar barracks, which were imploded in 2013. The ten-acre Hills section comprises, in ascending order of height, the twenty-foot-tall turf-covered Grassy Hill; the twin forty-foot rises of Slide Hill and Discovery Hill; and the seventy-foot-tall Outlook Hill, by a good margin the highest point on the island. Slide Hill is named for its four stainless-steel chutes of different lengths and gradients, contrived by the Canadian firm Earthscape Play; Discovery Hill surprises visitors with a hauntingly poetic, site-specific, concrete reverse cast sculpture by Rachel Whiteread titled Cabin; and one side of Outlook Hill, called the Stone Scramble, is inlaid with huge granite blocks salvaged from the island’s former seawall and composed into a huge child-friendly climbing cascade.

Though an exacting attention to detail is clear throughout the new park, less evident are subterranean measures taken to protect the island’s long-term survival amid inevitably rising sea levels. (With her mission fulfilled, Leslie Koch left Governors Island in June and will join a private urban planning consultancy.)

Symbolically, the completion of the Hills could not have come at a more opportune moment. During a season when mindless hatred against immigrants runs rampant in our land, the vista from the top of Outlook Hill offers an instructive panorama. It begins at the mouth of the Atlantic beyond the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, continues past the Statue of Liberty and her upraised torch in full frontal welcome, moves toward the longed-for gateway to freedom, Ellis Island, and then culminates with the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan, an unprecedented vision that thrilled new arrivals by sea well into the twentieth century.

The Golden Door, as the poet Emma Lazarus called this stretch of waterfront, has never been presented in a more inspiring visual perspective than is now available from Outlook Hill. With the view comes an implication of how the lives of the twelve million women, men, and children who passed through Ellis Island were immeasurably improved by American citizenship, to say nothing of those of their hundreds of millions of descendants. That alone is enough to make the brilliant architectural transformation of Governors Island a timely, uplifting, and sobering civics lesson.

The Hills on Governors Island will open to the public on July 19. The island is accessible daily by ferry from Manhattan’s Battery Maritime Building at 10 South Street, and on weekends from Brooklyn’s Pier 6. Kevin C. Fitzpatrick’s Governors Island: Adventure and History in New York Harbor is published by Globe Pequot Press.