The Democrats had two main goals at their party convention in Philadelphia: to knit the party back together following Bernie Sanders’s protracted challenge to Hillary Clinton and to portray their nominee in a more favorable light. Throughout the week, the momentousness of the history being made competed with the Clinton campaign’s quite evident strategic goals and was almost lost in them; but then, when the first woman presidential candidate appeared on the stage to claim the nomination, the importance of that moment was impossible to dismiss. A third goal was, of course, to undermine the legitimacy of Donald Trump as a possible president—an effort for which last week’s Republican Party convention had furnished with highly useful material.

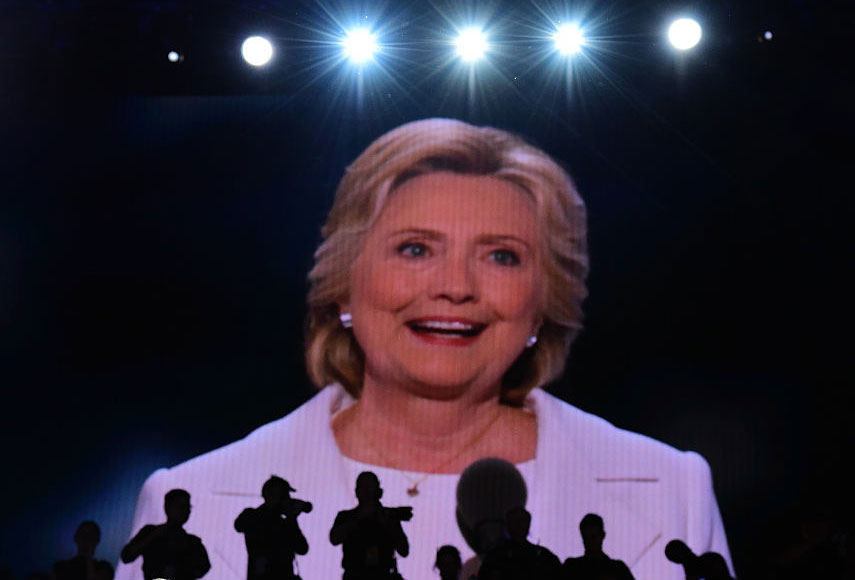

Past candidates have had their weak points, but it is the very unusual situation of Hillary Clinton that just as she has reached the pinnacle of her political career she’s also at her most unpopular. Still, in the huge convention hall the excitement of her officially becoming the nominee displaced that reality for all but a small clutch of the convention-goers. The convention had built toward that moment and for a while one could suspend the nagging worries about her and see her fresh. One had to wonder what it would have been like had those nagging worries not been there in the first place.

Clinton had taken quite a beating for having maintained the private email server and for not being truthful about it. And the Clintons’ assiduous seeking of great wealth had blurred if not blotted out her idealism. Surrounded by a retinue wherever she went and so obviously intent for so many years on winning the ultimate prize, she’d become the inaccessible Hillary. Compare her, for example, to Joe Biden; though Biden is vice president and has been living in a grand mansion he has remained accessible; people still think they know him and that he’s not out of reach. Even Bill Clinton, though also complicated, has maintained enough of the common touch, of his capacity for empathy, to not be a stranger to us. Hillary Clinton needed not a makeover but a stripping away of the layers of self-protectiveness and caution—and a slight excess of self-pity—for people to feel that they know her again. So she used her acceptance speech to remind the world that she’d spent most of her adult life wanting to improve the lives of those who need help, that she understands the uses of power. As the result of four nights of speeches and her own display of command of government programs—and the striking lack of that in her opponent—the woman who stood in her white pants suit on the large stage in the vast arena suddenly became a plausible president of the United States.

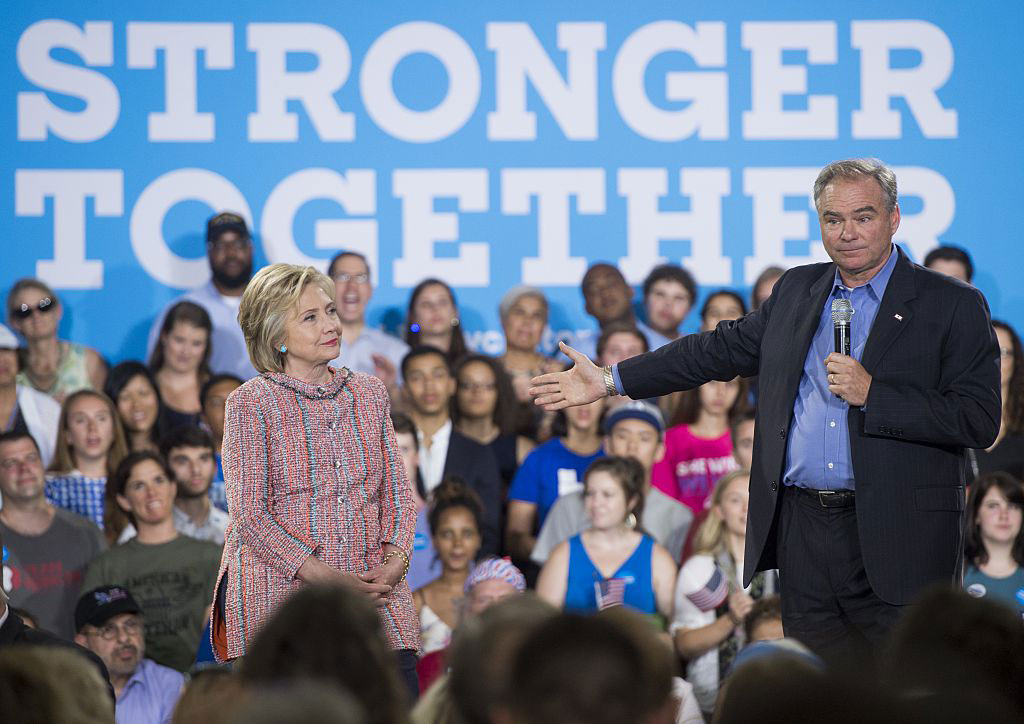

It’s hard to see how Clinton could have made a wiser selection for her running mate. Like Clinton, Virginia Senator Tim Kaine is serious about governing, and though he has the healthy ego of a successful politician he manages to keep it in check. He’s one of the most liked and respected members of the Senate, and of Congress as a whole. His likeability is of a different order from that of Trump’s running mate, Mike Pence. Pence is the good old boy who gets along with the guys; Kaine is held in high esteem by his Senate colleagues. When Kaine was named, I sent a note to Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, of Rhode Island, an unimpeachable progressive, asking what he thought of him. Whitehouse replied in an email: “LOVE Tim Kaine….If you graphed most progressive against best liked in the Senate, he’d be the outward mark.” Around the same time, Arizona Republican Jeff Flake tweeted: “Trying to count the ways I hate @timkaine. Drawing a blank. Congrats to a good man and a good friend.” (“Good man” being a phrase not loosely sprinkled about in the Senate.)

Having served on the Armed Services and Foreign Relations Committees, Kaine comes with broader policy experience than any of the other finalists, though Clinton selected him as much for his persona as for his credentials. From her experience during her husband’s presidency she was well aware of the need for compatibility between president and vice president. As Whitehouse pointed out to me, with the unflashy, unusually well-liked Kaine in the second slot, “she will never have to watch her back.” Kaine had a major part in obtaining, over White House objections, Congressional review of the Iran nuclear deal; and then in winning Senate approval of it. For the past few years he’s been leading an effort to get the Senate to enact authorization of the continued US fighting in Iraq and in Syria. This would give legitimacy to—and limit—US military involvement: the authorization would have to be renewed each year, and would bar the introduction of ground troops.

Advertisement

Sanders supporters, unrealistically hoping for someone on the far left of the party to be chosen by Clinton and apparently unaware of Kaine’s bona fides as a progressive, immediately raised objections to him. They used whatever they could get their hands on, in particular Kaine’s earlier support for “fast track” consideration of Obama’s trans-Pacific trade agreement (TPP). Clinton, who had initially backed the TPP, changed her position on it early in the campaign, and before the convention, Kaine, like a good vice-presidential running mate, said that he’d now oppose it. But this was of no difference to the Bernieites, many of whom carried signs with a red line through the letters TPP. (Opponents of the trade deal, who now include most of the Senate Democrats, suspect that it will be brought up in the lame duck session of Congress after the election in order to give Obama another victory.) Free trade just isn’t the totem it used to be: too many members of Congress now represent areas where previous agreements had cost—or were seen to have cost—jobs. Kaine got caught in the transition and Clinton almost did.

A Jesuit-trained social activist, Kaine had settled in Virginia, his wife’s home state, following Harvard Law School, and gone into civil rights law rather than seek to make a lot of money. In Virginia of all places he specialized in housing discrimination, where glory is rarely awarded. (That Hillary Rodham also went into social activism after law school is one thing that drew them together.) Kaine has a life apart from the Senate chamber; he’s a serious reader, a churchgoer, and a harmonica player (he keeps four of them in his briefcase) who frequently drops in on blue grass concerts in the hills of Virginia. Though gentle in demeanor he’s a politician to the core—he’s been governor, DNC chairman, and of course senator—and is fond of pointing out that he’s never lost a race.

Kaine knows how to appeal to a broad audience and did so in his acceptance address Wednesday night. He began somewhat uncertainly, but he got going with his folksy thing (“Hey, didja hear about…”) and interspersed his speech with Spanish (which he learned as a volunteer in a Jesuit mission in Honduras). Kaine was one of the major speakers who did a shout-out to the Sanders followers in the hall. His imitation of Trump—saying “Believe me” before outrageous claims—entertained the crowd and if few knew who Kaine was when he was picked, by the end of his speech he’d won most of them over. The hope is that he will also appeal to white middle-class workers, or unemployed ones, in the rust-belt states that Trump and Clinton are struggling over—and where the election could be decided. Trump’s been doing well enough in Ohio and Pennsylvania, and is eyeing Wisconsin and Michigan, to alarm the Clinton camp. Clinton and Kaine are to follow the convention by taking a bus trip through the hotly contested (as of now) industrial states of Ohio and Pennsylvania—Bill Clinton and Al Gore did a similar trip following the 1992 convention.

Mending the deep rift between Sanders and Clinton supporters proved more difficult than most people expected. Sanders’s behavior during his long campaign for the nomination, which went on well past its plausibility, signaled that he and his supporters weren’t of an inclination to concede defeat graciously. That Sanders supporters, in their recalcitrance, might conceivably throw the election to Trump didn’t seem to perturb many of them. Though in his speech Monday night Sanders made the required endorsement of Clinton, something in Sanders couldn’t be utterly generous. His strong showing—though significantly weaker than Clinton’s against Obama in 2008—and his devoted following were heady stuff. Even when it came to the roll call vote for the nomination Sanders held back. In 2008, Clinton came to the floor, interrupted the roll call and moved that the convention name the nominee by acclamation. Sanders didn’t do that. First, his side demanded a complete roll call, and then, in order to preserve on the record the number of delegates he had won—1,894 to Clinton’s 2,807—he moved at the end simply to have Clinton be named the nominee. He could well be keeping some distance in preparation for starting a protest movement after the election. He told reporters later that he’d return to Washington as an independent, not as a Democrat, even though he’d run for the party’s nomination. Sanders clearly has plans.

Advertisement

The Clinton campaign’s determination to concede as much as possible to Sanders in the party platform meant that she yielded on providing free tuition in public colleges to families earning up to $125,000, the goal of a $15 minimum wage, and offering a public option as part of Obamacare—policies that liberated her from the innate cautiousness earlier in the campaign that had left so many Democrats dispirited. But many Sanders supporters, young and new to politics, didn’t accept that attaining their goals requires compromises, and so they sought to have their way long after it should have been clear that they couldn’t. This was Sanders’s fault as much as their own, and it led to a ragged opening of the convention.

The Sanders crowd—especially in the California delegation—heckled speakers and showed their resentment for Clinton for passing over Elizabeth Warren as her running mate. Frankly, it never made sense that Clinton would pick Warren, whose strength is being outspoken in her outrage over corporate ripping-off of consumers. Vice presidents have to subsume their egos and cannot have an agenda separate from the president’s. Also the president needs their help in dealing with Congress, and, unlike Kaine, Warren is far from universally liked on Capitol Hill. It took an exasperated Sarah Silverman, a true Bernieite, on the first night of the convention, to at last tell off hardcore Sanders supporters from the podium. “You’re being ridiculous.”

The fraught situation wasn’t helped by the release, on the Friday before the convention, of nearly 20,000 emails hacked this spring from the DNC email server; even the forced resignation of DNC chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz didn’t mollify Sanders’s followers. Though all good Democrats had to profess shock that the DNC staff favored Clinton, more experienced political participants and observers weren’t surprised. Of course it was unattractive for one DNC staff person to suggest the planting of questions about Sanders’s apparent lack of practice of his Jewish faith, but it’s not at all clear that this ever happened. (More interesting than the fact of the emails’ existence was the source of their exposure: WikiLeaks, headed by Julian Assange, who had made clear his personal animosity to Clinton and timed the release to cause maximum damage to her convention strategy of trying to heal things with Sanders’s people.)

The involvement of Russia in the hacking of the DNC, confirmed by several security experts, created a new wrinkle: Putin didn’t have to be running Trump—which no one seriously claimed—for Russia’s meddling in our politics to be a very worrisome matter. (Though some Trump followers thought that focus on this was a deliberate distraction from the substance of the emails, which of course they found shocking.) Trump’s clumsy suggestion in a press conference on Wednesday that Russia try to get the 33,000 emails Clinton said had been deleted from her personal server showed the dangers of someone who doesn’t know much of anything about foreign policy being in the presidency.

By Monday night, after Michelle Obama’s extremely well-received speech, most of the Sanders faction appeared to calm down. (A group of them were still booing during Clinton’s acceptance speech, but they were essentially drowned out in all the excitement.) The enthusiastic reception of Michelle Obama had a lot to do with the intensity and polish with which she spoke—this was a woman who eight years before had barely disguised her contempt for politics. She and her husband were also given great credit for having raised two poised and mature young women during what could have been difficult years to live in the White House. Like her husband a graduate of Harvard Law School, Michelle had given up a career to be a successful First Lady, throwing herself into unexceptionable causes—such as nutrition and exercise.

In her speech, Michelle Obama initiated one of the major convention themes: “Don’t ever let anyone tell you this country isn’t great.” Reflecting on how to deal with Trump, her reciting of the Obamas’ family motto, “When they go low, we go high,” received strong applause. Her startling line about waking up every morning in a house that was built by slaves got the audience’s attention. Michelle Obama still has an edge—she’s the descendant of slaves—but one that doesn’t cause unease. (Bill O’Reilly was moved to state later that the slaves who built the White House were well clothed and well fed, a variation on an old southern myth.) Though Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton had never been close, she gave Clinton strong backing. The thing is, her husband needs Clinton to win, partly as vindication, partly because his legacy is at stake, and partly because he abhors the idea of Donald Trump in the White House.

The Democrats happen to be blessed at this time with unusually gifted speakers, including the two men who are probably the best in politics right now—the current and previous Democratic presidents. Bill Clinton did a brilliant thing on the stage on Tuesday night, painting his wife as “the best darn change agent I ever saw”—a mantle the Republicans had put on Trump. In fact the Democratic convention did quite a bit of mantle-snatching this past week. Having been given the opening by Trump, Democratic speakers portrayed their party as the optimistic one—Reaganesque—and they even absconded with patriotism: now it was the Democrats who were chanting “U-S-A, U-S-A”—a cheer first heard at the Republican convention in 1984, following American victories in the Olympics in the United States.

Aiming to make his wife more likeable, Bill Clinton told story after story about her determination to help people (“always making things better”)—as he chipped away at the Goldman Sachs crust she’d acquired after leaving the State Department. The stories have validity: Hillary Rodham Clinton was the idealist her husband portrayed her as being; there’s a through-line from her early post-law school days to her championing of the causes of women and children in the White House, the Senate, and even the State Department. Clinton described a Hillary few people know, especially younger women (whose support she’s having trouble attracting); through his stories he showed how her mind worked to solve problems for everyday Americans, whether it’s providing health care for children or legal aid for the poor. Bill Clinton may have slowed a bit but he still can hold a hall rapt.

Like other speakers Bill Clinton sought to put some meaning in the Clinton campaign’s eventual choice of a slogan, “Stronger Together,” bland though it seemed at first blush, and by the end of the convention it actually seemed to mean something. Trump had done Hillary Clinton a favor by claiming, “I alone can fix it”—whatever the problem was.

The all-star cast of Wednesday night—Biden, Kaine, and Obama—was like an oratorical show. Each one stepped up and gave it his best shot. The surprise was Mike Bloomberg, the authentic billionaire (wealthier than Trump), an independent, who was in a position to make withering comments about Trump. Bloomberg’s line—“I’m a New Yorker and I know a con when I see one”—not only buoyed the audience but was a balm for those troubled by Trump’s lack of authenticity. Finally someone who was in a position to was calling out his vaunted business record as a sham. Bloomberg made a pitch to Republicans and independents to back Clinton. His ad-libbed line that brought down the house (and set Bill Clinton, seated in his own box, into peals of laughter), “Let’s elect a sane, competent person,” released the audience to indulge for a moment in open acknowledgment of one of the big questions that float above Trump: Is he crazy?

I was particularly struck by the difference in the speeches by the president and vice president. In one sense each was sticking to his own style; in another, they were speaking to different audiences. Biden makes a big thing of his blue-collar childhood (after his once-prosperous father lost his money in the Depression), of his birthplace being Scranton, Pennsylvania, a rust-belt town badly suffering from the changed economy. (Trump spoke to a packed audience in Scranton on Wednesday.) Biden, who has complained openly that the Democrats don’t know how to talk to blue-collar people, did just that. Referring to Trump, he said: “He’s trying to tell us he cares about the middle class. Give me a break. That’s a bunch of malarkey.” Biden’s testimonial to Hillary Clinton was strong but not without its poignancy. The world knows that Biden would have liked to run for president this time but finally decided against it after the death from cancer of his beloved son Beau. This was likely one of Biden’s last major appearances, though he’s dropped hints that he’ll stay around in public service—perhaps on his anti-cancer “Moonshot” initiative.

But it was Barack Obama who picked up the flame of America’s greatness and ran with it. Annoyed with Trump’s dark portrait of the country, Obama had been longing to give such a speech, but had to wait for the right moment in the campaign. He said, “I’m more optimistic about the future of America than ever before,” and he rattled off a list of positive statistics about the state of the economy. Noting, as other speakers had, that the convention arena was near Independence Hall, he did a long riff on the meaning of our democracy—which ordinarily wouldn’t have been required, but Trump had made it so. In an allusion to Trump’s authoritarian streak, the president said, “America has never been about what one person says he’ll do for us. It’s about what can be achieved by us, together, through the hard and slow and sometimes frustrating, but ultimately enduring work of self-government.” Obama spoke with an urgency about this election. He said, “It’s not just a choice between parties or policies, the usual debates between left and right. This is a more fundamental choice about who we are as a people, and whether we stay true to this great American experiment in self-government.”

The president mocked Trump, saying, “You know, the Donald is not really a plans guy. He’s not really a facts guy, either.” Trump’s evident lack of preparedness to govern—and his evident lack of interest in learning some of what he needs to know—was a major theme of the convention, especially when set off against Clinton’s long record of government service and preparation. Obama also followed up Biden’s questioning of Trump’s bona fides as the champion of the middle class: “Does anyone really believe that a guy who’s spent his seventy years on this Earth showing no regard for working people is suddenly going to be your champion? Your voice?” (In his acceptance speech, Trump had claimed to be the voice of his followers.) And Obama continued the string of attacks on Trump’s business practices—strip him of his business and there’s nothing left for him to claim: “He calls himself a business guy, which is true, but I have to say, I know plenty of businessmen and women who’ve achieved remarkable success without leaving a trail of lawsuits and unpaid workers and people feeling like they got cheated.”

Obama made Clinton’s long pursuit of the presidency into an asset: “I can say with confidence there has never been a man or a woman, not me, not Bill, nobody more qualified than Hillary Clinton to serve as president of the United States of America.” It was hard to recall the two of them as bitter rivals eight years ago.

Yet Obama’s speech, technically brilliant as it was, left me wondering how much good it would do in the fall. He didn’t seem to speak to the audience the Democrats most need to reach, and the optimistic America he described was a different place and irrelevant to those still looking for jobs or for better pay. He made only a glancing mention of the idea that there’s more work to be done. Obama and Clinton’s long hug at the end was moving to the audience at hand though the Republicans, who portray Obama as hopeless failure, say that it gave them excellent material.

The emotional buildup to Clinton’s acceptance speech reached its apex when a Muslim man, standing at the podium with his wife, both immigrants whose son had died in Afghanistan protecting his fellow US troops, pulled out his copy of the Constitution, asking Trump if he’d ever read it, and charging, “You have sacrificed nothing, and no one.” This seemed to take the convention’s collective breath away.

Following an introduction by daughter Chelsea (a parallel to Ivanka Trump’s introducing her father at the Republican convention), Hillary Clinton couldn’t have been under more pressure when she gave her acceptance speech. As she admits, she’s no great orator; her speeches are prosaic, though she tries to make up for that with seriousness of purpose and command of policy. Her few clever lines came across as goodies dropped into her remarks by speech writers; they had little consistency with the tone of the overall speech. The story we were told for the umpteenth time about how her mother made her go back to the street and confront a neighborhood bully—perhaps a message to Congress—could be retired, and her insistence that she’s been knocked down but has gotten back up is becoming a bit tedious.

In her speech, Clinton attempted to accomplished several things. One of those was to turn Sanders possibly into an ally, by offering extensive gratitude for making her a better candidate—which he had. (Sanders, in the audience, sat there stone-faced.) She showed that she could command the hall for a lengthy presentation: it was hard to equate this polished speaker with the halting one at Roosevelt Island, site of the restart of her campaign last year. And she made it clear that she has actual plans; as opposed to Trump, she offered a large vision for addressing the economic situation.

Like other presidents since FDR, she had her own hundred-day plan: to work with the Republicans (assuming they’re willing) to make a large investment in the creation of new jobs, including a major new infrastructure program. She also cited a sweeping number of items she’d propose–increased minimum wage, debt-free college tuition, broadened health care, expanded Social Security, a curbing of corporate profits and taxes on companies who relocate overseas, tax increases on the wealthy, paid family leave. This was a liberal program but intended not to be so encompassing that it would put off independents or even some Republicans, whom convention speakers had tried to lure. But it was a far more progressive approach to governing than what her husband had proposed; it was a new day and a new Democratic party. Seeking to offset Trump’s claims, Clinton pronounced, “Democrats, we are the party of working people,” and, echoing Biden, she said, “We haven’t done a good enough job showing that we get what you’re going through.”

The Democrats had put on a successful convention. Amid the inevitable balloon drop and the knowledge that we’d witnessed history, the euphoric delegates could be removed from reality for a brief time. It’s easy to get caught up in a convention’s joyous mood (if it has one, which the Republicans’ didn’t) and forget for a moment that there will follow—especially this year—a very rough contest for the presidency.

Part of Elizabeth Drew’s continuing series on the 2016 election.