There is much to admire in the early modern art of the United States, but from today’s vantage point the works of two painters in particular stand out: Edward Hopper and Stuart Davis. In some respects Hopper, despite the obvious anachronisms of his pictures, strikes many as the more current of the pair. His brand of atmospheric realism—in part kept alive by film directors on whom he has had a profound influence—seems ageless or, more accurately, suspended in time, providing continually apposite decor for our native anxiety and ennui. The work of the decidedly upbeat and more overtly stylish Davis, on the other hand, may appear to be dated with its period graphic tropes, yet the abiding immediacy of his painterly manner has given it an enduring, if less noted, presence in the evolution of US art.

For those who, like me, are longstanding and unwavering fans of Davis’s work, the current show at the Whitney, “Stuart Davis: In Full Swing”—put together by Barbara Haskell, that institution’s resident expert in prewar modernism and Harry Cooper, curator of modern art at the National Gallery of Art, where the show will travel in November—is a welcome occasion to re-experience his bracing achievement. On that basis alone it is even more appreciated in this white-knuckle summer of our country’s discontent. For those previously unfamiliar with the blazing color and syncopated rhythms of works such as Report from Rockport (1940) and Rapt at Rappaport’s (1951-1952)—and much of the mission of museums consists of introducing rising generations to the “old new”—the exhibition is, in the main, a carefully conceived and expertly realized introduction Davis’s electrifying contribution.

As with the work of Piet Mondrian, with whom he became briefly acquainted when the Dutchman, fellow jazz aficionado, and author of Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-1943) took refuge in New York during World War II, the “spontaneity” of Davis’s paintings was as meticulously prepared and rehearsed as a Coleman Hawkins saxophone solo. The decade-wide parentheses in dating of Ultramarine (1942-1952) and American Painting (1932/1942-1954)—both almost mosaics of eccentrically cropped chromatic fragments—testify to the protracted gestation of works that look as if they’d been speedily and effortlessly knocked out. Like Mondrian, Davis taped off areas of his canvas to be filled in with no-fuss-no-muss strokes, a technique that allowed his hand to leave its mark without the obviously emotive “gesturalism” of Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Philip Guston, whose New York School supplanted Davis and his cohort.

Within the almost cloisonné compartments from which Davis’s images are assembled, rich, expansive tides of buttery pigment lap up against the bounded margins of shapes, allowing liquid oil paint—rather than the painter’s psyche—to speak for itself. He was a hedonist to the core but also a materialist. Equal, therefore, to his gift for locking in allover pictorial structures replete with eye-popping incident, was his mastery of the loaded brush. Like the base beat backing up varied timbres of a horn section, his mark-making was steady and sure but never rote.

Davis was New York’s quintessential Jazz Age artist, the Eddie Condon of his medium. In fact, the Whitney catalog reproduces a photo of the two together at Condon’s club in 1946 as well as another 1943 shot of Davis posing in front of a canvas with Duke Ellington, whose hipster aphorism “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing” Davis quotes in one American Painting (1932/1942-1954). Davis’s close contemporary, Archibald Motley, the Paris and Chicago-based Afro-American artist, whose work was the subject of another recent survey at the Whitney (organized by Richard Powell), laid down his own painterly licks in a different, mellower groove, proving, as if proof were necessary, the breadth of Jazz’s influence on painting between the two world wars. And after: in 1947 Henri Matisse, in all probability exposed to Davis’s work during his visit to the United States in 1930, published his glorious print portfolio Jazz.

Davis was also the only first-class Cubist to emerge from North America. In my estimation he was the equal of the great Fernand Léger, who so loved New York’s tumult and muscularity but failed to capture it in his own works devoted to the subject, such as the Davis-inflected Adieu a New York (1946). I would even argue that, painting-by-painting, Davis was in some respects Léger’s superior—the painter and critic Fairfield Porter astutely noted that “Léger’s reserve force is the alibi for his inattention” despite the fact that, along with Picasso and Braque, the Frenchman undeniably originated the formal language that Davis refined, tuned up, and gave uniquely New World accents.

Advertisement

All of which makes it regrettable that Haskell and Cooper chose to entirely omit the developmental stages of Davis’s long and complex career in the current show. Their account seriously truncates the story of how, in the Teens and Twenties of the last century, artists of his generation on this side of the Atlantic found their way to full-tilt modernism through more or less extended apprenticeships to Naturalism and Post-Impressionism. Davis acquitted himself exceptionally well in both, passing through Ash Can School social realism primarily as a cartoonist/illustrator for The Masses, and then, during summers on Cape Ann, bringing can-do Yankee craftsmanship to the visionary idiom of Van Gogh, in landscapes and self-portraits. After the darker heavier palette of his Ash Can years, works such as Self-Portrait (1912) featured unusually vivid juxtapositions of high-keyed primaries and radiant secondaries in which the local colors of that rocky coast line blush turquoise, lavender, and pink.

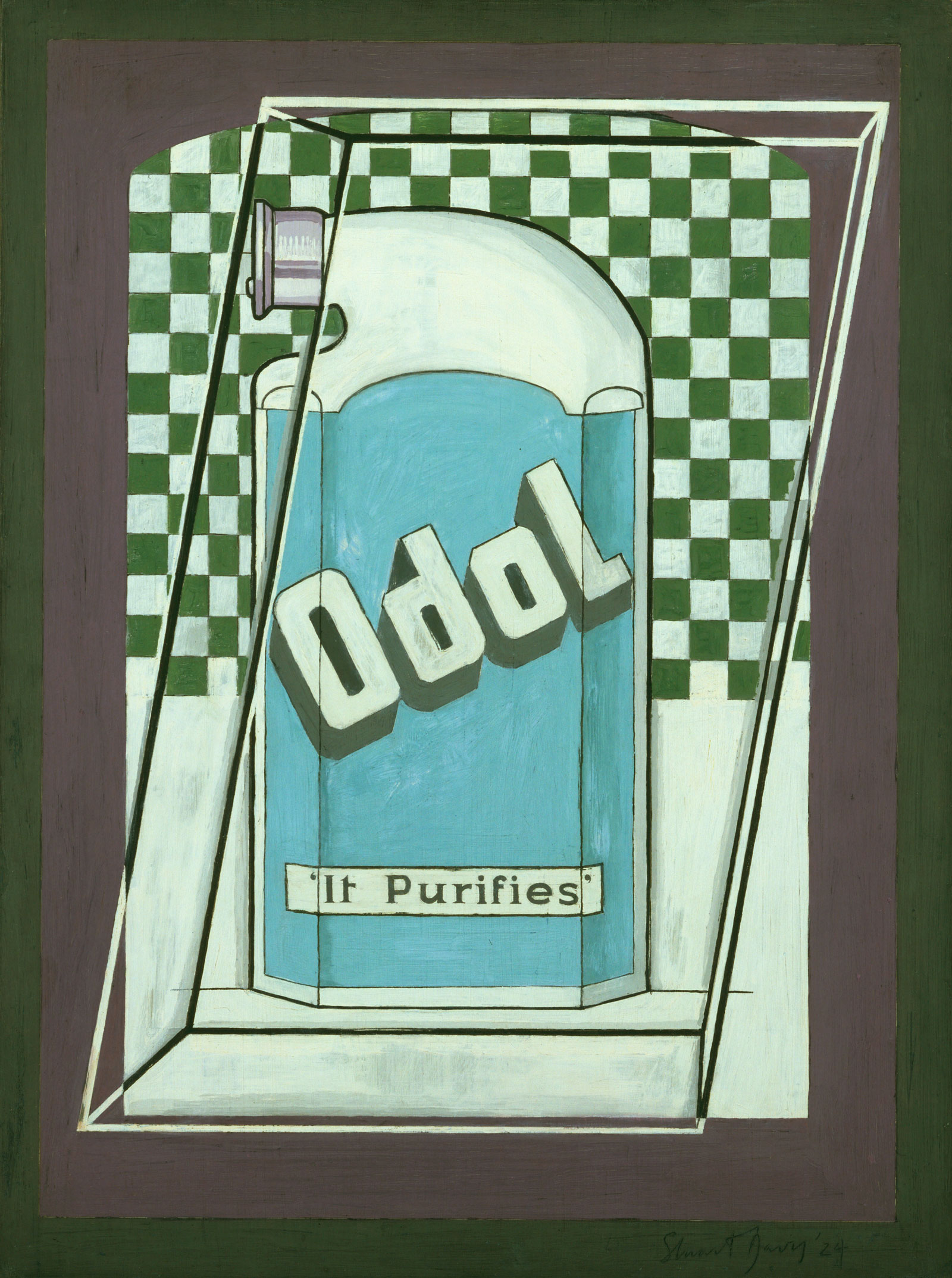

These striking contrasts and idiosyncratic admixtures or tints provided the spectrum of Davis’s first truly modernist compositions in the 1920s: dense still lives of household appliances—a coffee percolator and an egg beater, the latter having served as his “muse” for a suite of four near-abstractions in which he worked through the problems of synthetic Cubism as he found it and forged his own manner. Like many in his generation, Davis was a heavy smoker and drinker and his pronounced sensuality (seldom overtly erotic) is everywhere in both his imagery and his tactile and chromatic treatment of it. Thus Haskell’s show starts with a group of collage-like studies of smoking supplies—a bag of tobacco in Sweet Caporal followed by Cigarette Papers, Lucky Strike, and Bull Durham (all 1921), and in a more conventional set-up a pipe, tobacco tin, Zig-Zag papers, and a sports tabloid with a cartoon above the fold in Lucky Strike (1924). Obviously savoring the visual punch of their packaging, Davis often painted readily identifiable commercial products. Most notable was Odol, a mouthwash sold in a distinctively shaped bottle with bold typography, which “posed” for two canvases in 1924, the most iconic of them being a widely recognized precursor of Pop that Kirk Varnedoe acquired for the Museum of Modern Art in 1997, six years after his signal but much-criticized exhibition “High & Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture.”

More’s the pity then that the present Whitney retrospective does not include Davis’s 1930 Eggbeater V—also in MoMA’s collection—which shows Davis mimicking the “gueridon” (pedestal side table) compositions of Picasso and Braque. The missing picture is a spirited assimilation of their devices and a benchmark for the greater radicality of his other renditions of the subject, some of which depart from the School of Paris models and enter into the Central and Eastern European variants on Synthetic Cubism that were pursued in the United States by Arshile Gorky (his Garden in Sochi cycle of the late 1930s through mid-1940s has interesting parallels to Davis’s earlier but equally paradigm-setting Egg Beaters), Ilya Bolotowsky, Carl Holty, and Ad Reinhardt, all of whom knew and respected Davis.

In view of the political upheavals of the 1930s, Davis’s decision to transform American art by focusing on such domestic items was, as a matter of studio strategy, in keeping with Picasso’s and Braque’s embrace of classic pictorial genres inherited from the Dutch, Spanish, French, and German Old Master tradition. However, by the time Davis fell in line, Dadaist, Futurist, and Constructivist sons had openly if not rudely challenged the “bourgeois” conventions of their Cubist fathers in ways that effectively highlight the confident irony of Davis’s choice. For him, it would seem, the modern world was exciting enough in its own right; for him a humble egg beater was as apt a symbol of the new age as a turbine, the commonplace as worthy of our attention as the heroic. An apparently bonhomous and essentially sanguine man, Davis was a citizen of Walt Whitman’s New York rather than revolutionary Paris or Petrograd or Berlin.

Which is not to say that he was indifferent to politics. An activist of the non-Communist Left, Davis was among the first artists of his caliber to sign up for the mural division of the PWAP (precursor of the WPA) in 1933, and a year later he joined the unapologetically Marxist Artists’ Union—of which he was subsequently elected president. It is telling that many of his contemporary admirers are Neo-Conservatives who condemn public funding of the arts and excoriate the “political art” of today even as they celebrate him. A corresponding discrepancy in awareness hovers over their admiration for Reinhardt, who also drew for The Masses while pioneering formalist abstraction. Moreover, Davis was a man so imbued with the lust for life that he was incapable of producing dull or depressing art and plainly would have never understood how such art, or a deliberate denial of pleasure, could be “good for the cause”—any cause.

Advertisement

From his breakthrough in the mid-1920s until his death at seventy-one in 1964, just as the wave of Pop artists—to whom he gave courage and taught ways of seeing and doing—crested, Davis concentrated single-mindedly on making art quiver with the energy he perceived around him. Jazz was an inherently urban music, but in Davis’s art its pulse could be felt everywhere, from Hudson River docks to small seaport towns in New England where swing bands and bebop combos—not to mention African-Americans—were few and far between.

Some of his techniques for abbreviating and “jazzing up” details of the American Scene, in particular its stereotypical attributes, advertising hieroglyphics, and verbal colloquialisms, may now seem corny, in part because they were so widely and formulaically copied by commercial artists cranking out record covers and restaurant menus. Davis himself designed some LP sleeves and a few may now appear embarrassingly cartoony as a result of the influence he had on animators in the film industry. But there again his work did much to introduce hacks to modernist tropes, giving them new freedom to play with forms rather than merely render them. While Davis’s impact on Pop Art is obvious, in particular on Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Indiana, it is also palpable in the work of the Hard Edge abstractionists Al Held and Ellsworth Kelly, as well as in that of contemporaries like Jonathan Lasker and the late Elizabeth Murray. That Davis was wise to the complications inherent in his popularity may be implicit in the title of a starkly one-dimensional late painting, Cliché (1955), and the more intricate study for it.

That said, the core of the Whitney exhibition shows Davis applying his methodology to easel paintings of varying sizes—including small, amazingly intricate jigsaw-puzzle compositions such as Arboretum by Flashbulb (1942) and Ultra-Marine—while periodically struggling to give his art the mural dimensions that the billboard bravado of his style seemed naturally destined for. Only two works on view achieve that scale, Swing Landscape (1938) and Mural for Studio B, WNYC, Munipical Broadcasting Company (1939), while Men Without Women, Radio City Music Hall Men’s Lounge Mural (1932, now in MoMA’s collection) demonstrates how such ambitions could misfire, losing the snap that Davis’s pictorial idiom required.

Several Davis motifs, whose multiple iterations are skillfully juxtaposed in Haskell’s groupings, reveal him at his best as a painter for whom the challenge of composing variations on a theme was as fruitful as reinterpreting standards at different tempos, or with different dynamics and different orchestrations, was for Ellington, Count Basie, and other Big Band arrangers. Thus Little Giant Still Life (1950) and Visa (1951) and Little Giant Still Life (Black and White Version) (1953) and Switchski’s Syntax (1961) are all emblazoned with the Champion Spark Plug’s brand name. Set against otherwise fairly consistent marginal and background configurations, each work nonetheless jitters and shakes with a distinct optical rhythm. So too The Paris Bit (1959) and Study for “The Paris Bit” (1951/1957-1960) reprise the accordioned Parisian street scenes first painted during Davis’s only sojourn in Cubism’s capital in 1928-1929.

The exhibition ends abruptly with an unfinished, still partially-taped canvas, Fin (1964), in which one can plainly follow the artist’s moves. Although the title indicates that Davis felt that the end—la fin—was close, one takes satisfaction in knowing that the verve that transformed him from an earnest, provincial modernist into a rousingly inventive cosmopolitan was undiminished.

The history of art is as much a matter of its changing reception as its genesis. Back in the 1980s, I concluded a review of a small Stuart Davis show with words to the effect that “Stuart Davis’s work is enough to make you feel that the twentieth century wasn’t such a bad deal after all.” My editor, a student of Frankfurt School cultural criticism at Columbia, acidly called my statement terribly naïve. Having witnessed some of the worst that the late 1960s and early 1970s had to offer in the US, France, and Mexico, I was incensed rather than intimidated by his academic condescension. I didn’t need to be told how bad things could get; I was speaking of how good they could be and how sustaining great art was even in the grimmest of times. Seeing this Davis retrospective against the background of terrible events in the world at large and agonizing violence and divisiveness at home, I’ll stick by that judgment.

“Stuart Davis: In Full Swing” is at the Whitney Museum through September 25. It will continue at the National Gallery of Art in Washington from November 20, 2016 through March 5, 2017, at the de Young Museum in San Francisco from April 1 through August 6, 2017, and at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas from September 16, 2017 through January 8, 2018.