It was around 2002 or 2003 that the latest round of the great onslaught on African wildlife began. Conservationists across the continent started noticing the same thing: a growing proportion of dead elephants had been illegally killed, often with their faces sawed off and tusks dragged away. The rise in elephant poaching seemed closely correlated to China’s economic progress. China’s economy was booming in the early 2000s, and in China, ivory is coveted as a status symbol, carved into bracelets, bookmarks, shot glasses, statuettes, and combs. As China’s middle class grew to the hundreds of millions, one of the most advanced life forms on the planet—which wildlife experts have long been especially interested in for its intelligence and human-like social behavior—was being wiped out for trinkets. And it was being abetted by pervasive corruption, extreme poverty, and instability in the regions of Africa where the elephants were found. This was globalization gone wrong.

By 2010, more than 30,000 African elephants were being killed each year, a rate faster than the population could reproduce. It was reminiscent of the 1980s, when the African elephant population was halved, leading to an international ban on the commercial ivory trade in 1989. That ban and the accompanying public awareness campaign helped shift perceptions about ivory, discouraging Western and Japanese consumers from buying it. Elephant populations began to recover in the 1990s and early 2000s.

But then soaring demand from China pushed the price of ivory irresistibly high and destitute poachers across Africa were willing to risk their lives to down elephants. Today, wildlife experts speak of an “elephant holocaust.” Not since the late 1800s, when Europeans went plunging into Congo and other parts of Africa in a quest for ivory for billiard balls and piano keys, “the vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience,” as Conrad put it, has such a large chunk of the elephant population disappeared. Minka Kelly, a television actress, recently tried to stir people to action by saying that by the time you finished a cup of coffee—or for that matter, reading this article—another elephant would be killed.

These animals have suffered all manners of death. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, elephants are shot in the top of the head by high caliber rifles from helicopters, most likely flown by African armies, some of them American-funded allies. In Kenya, their hides are pierced by poison arrows. In Malawi, poisoned pumpkins are rolled into the road for the elephants to eat, resulting in a slow, agonizing death while the poachers watch. The newest problem is the sudden death of many vultures. These scavengers are the savannah’s natural alarm bell, circling in the sky and waiting patiently in the trees, tipping off rangers to where poachers have recently been active. Sprinkle some insecticide on the carcasses for the vultures to ingest and you can kill many more elephants without ever being detected.

The regions of Africa that have suffered most from poaching are those steeped in conflict, where it is too dangerous for conservationists to work. A few years ago, Janjaweed militiamen from Sudan tromped more than a thousand miles to slaughter hundreds of elephants in Cameroon in the span of a few days. In the Central African Republic, torn by religious conflict, some of the local elephant populations may soon go extinct.

When I visited Congo’s Garamba National Park a few years ago, I saw for myself what happens when war meets elephants. Garamba is situated in the middle of three different conflicts—South Sudan’s civil war to the east, Central African Republic’s to the west, Congo’s ongoing chaos to the south. Garamba’s rangers don’t wear scout uniforms or floppy hats like their counterparts in most other parts of the world. Instead, when they set off for work each morning, they suit up for battle: helmets, vests, bandoliers, assault rifles, belt-fed machine guns, and rocket-propelled grenades. Every year dozens of wildlife rangers are killed by the armed groups that have eagerly stepped into the poaching business. Ivory is Africa’s newest conflict resource, the twenty-first-century version of blood diamonds. Some of the most brutal groups—Somalia’s Shabab, the Lord’s Resistance Army, the Janjaweed, and Congo’s Mai Mai militias—are now trading in ivory, using it to fuel their bloodshed.

And there’s another threat, possibly even deeper and harder to root out than war: corruption. Ivory trafficking hinges on widespread government corruption because of the distances and logistics involved in getting a piece of an elephant from the African bush thousands of miles to the underground ivory markets in Hong Kong or Beijing. My research and others’ has shown that the whole illicit chain is lubricated by sticky-fingered police, port officials, and other bureaucrats on both sides of the ocean, who are bribed to allow illegal ivory shipments to slip through. It is the same for the horns of rhino, also being intensively poached to feed a vast Asian market. (Many Chinese and Vietnamese people still believe ground-up rhino horn is a superb medicine for everything from headaches to cancer.) Wildlife trafficking now mimics drug trafficking or human trafficking; it’s inextricably linked to organized crime. In Sudan, I learned that there was a well-worn practice called “buying time” in which smugglers pay police officers and border guards a certain fee per hour to get their goods through checkpoints.

Advertisement

Or consider the case of Tanzania, a wildlife haven and one of Africa’s most peaceful nations. With the same political party in power since independence fifty years ago, Tanzania is essentially a one-party state, and lacks the checks and balances of other emerging democracies. Tanzanians remain trapped in grinding poverty partly because so many public resources are stolen or frittered away by corrupt officials. The natural environment also suffers. Several years ago, the Tanzanian government was implicated in illegally shipping a planeload of live animals, including baby giraffes, to Qatar. Government officials have also leased protected land to a company that has allowed hunters to run over animals with a truck. Still, there may be no worse victim of environmental mismanagement and corruption in Tanzania than the Selous Game Reserve in the southern part of the country.

Named after Frederick Selous (1851-1917), a Victorian adventurer who spent years hunting game and collecting specimens in this area, the Selous is among the largest wildlife reserves in Africa, 50,000 square kilometers, bigger than Switzerland. Its incredibly varied landscape is rippled with green hills, crossed by rushing rivers, cut by rocky gorges, and soggy with swamps. Its creatures include the big shots of African wildlife: lions, leopards, hyenas, giraffes, hippos, sixteen-foot-long Nile crocodiles, and very rare bat-eared wild dogs—as well as what was once one of the largest elephant populations in Africa. Its flora is just as spectacular, Baobobs with trunks twenty-feet wide and two thousand other kinds of plants and trees. Because the Selous is home to the tsetse fly that kills cattle and gives people African sleeping sickness, it has remained remote and unpopulated for eons. (Selous himself died on the banks of the Rufiji River here, cut down by a German sniper in 1917, during World War I.)

Today, however, the Selous, and especially its elephants, are in crisis. Because of what is widely suspected to be collusion between local officials and ruthless poachers, Selous has recently lost nearly 90 percent of its elephants. A census in 1976 indicated there were 109,000 elephants in the Selous; now that number is perhaps less than 15,000. Each day in the park, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, an estimated six elephants have been killed.

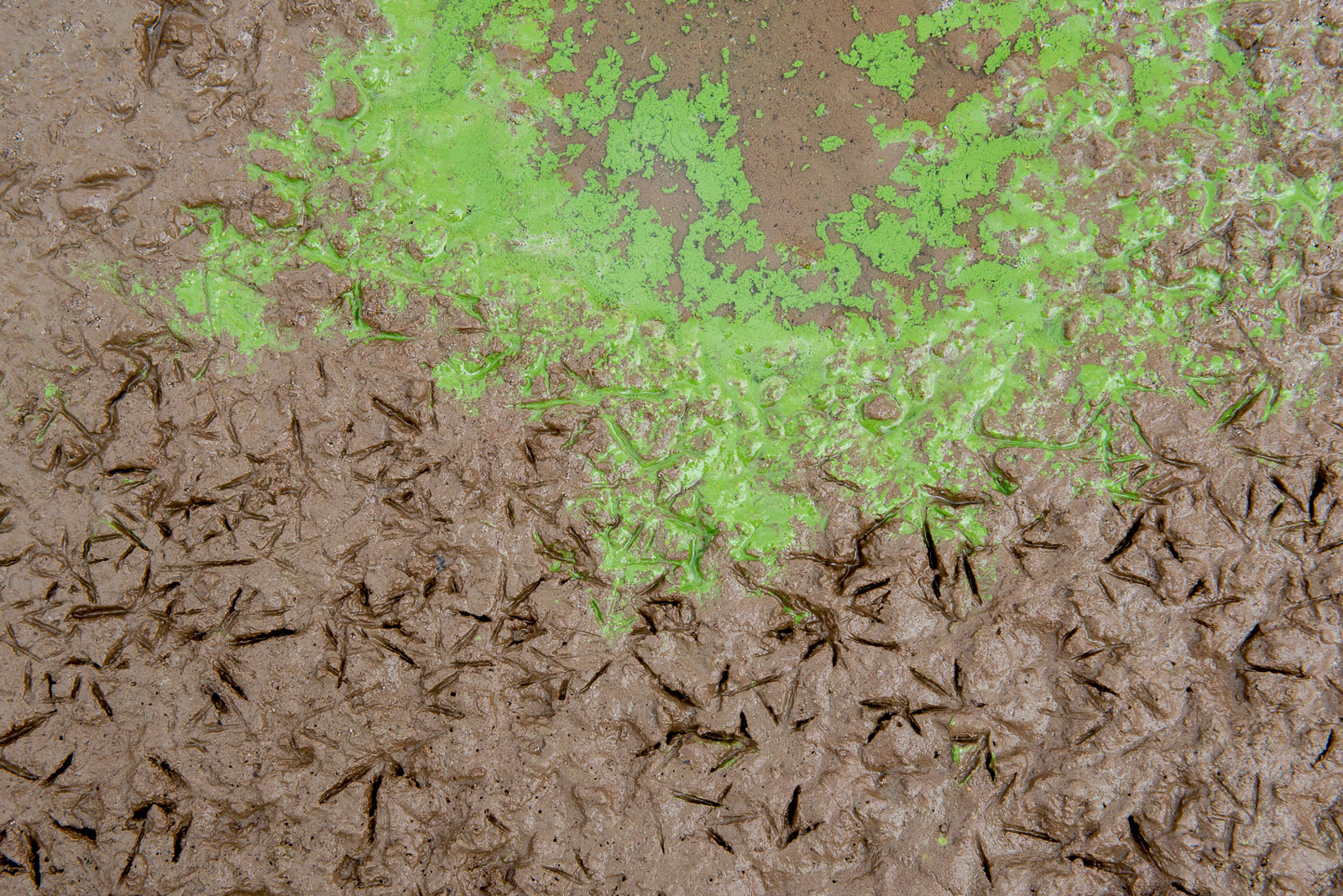

This is probably the best reason to open Robert Ross’s new book of photographs of the reserve, Selous in Africa: A Long Way from Anywhere. According to the biographical note on the dustjacket, Ross, a native New Yorker, turned to wildlife photography after “wisely leaving a career in property finance and development.” I’m glad he did. There are countless books on African wildlife and this one partly hews to the classic formula of giraffes in golden light and a sherbet-colored sun sinking into the doum palms. But Selous is also a record of what is at stake, a set of portraits of the extraordinary wildlife we are losing. One senses, more strongly than in other books of this kind, that Ross wants to bring us into a fast disappearing world and keep us there. Many of his most interesting pictures are not of lions or leopards or slit-eyed crocs, though there are plenty of those, but of tiny insects crawling across leaves, animal tracks pressed into the mud, clouds smeared across the Tanzanian sky.

One of my favorite images was the two-page spread of hundreds of red-billed quelea, the world’s most abundant wild bird species, in flight, a few patches of blue sky peeking out through the blizzard of beating wings. Or the shot of a housefly catching a ride on the back of a Diplopoda millipede and the one of a fish eagle flying away with a wriggling baby croc in its talons. There are several strong images of elephants, though majestic “tuskers,” as they are called in east Africa, were clearly not Ross’s focus. His camera seemed to be always searching, not for anything in particular but for anything interesting. Ross said his 276-page book was the product of more than 100,000 images shot over four years. The sheer amount of life in the Selous, and in these pages, is staggering.

Advertisement

The war against poaching grinds on. In some countries, like Kenya, politicians have finally woken up and passed stricter laws against ivory trafficking, and major traffickers have been arrested and punished. It is in Kenya’s interest; wildlife tourism is one of the biggest sources of foreign currency. In China, the anti-ivory campaigns by Chinese celebrities like Li Bingbing, a leading film actress, and Yao Ming, the former NBA player, may be starting to have an effect. The price of ivory on China’s streets has dropped from $2,000 to $1,000 a kilo. But African rhinos are still get plucked off at a distressing rate, with the street price for rhino horn at $60,000 a kilo—more than cocaine. Or gold.

Though the Selous feels like another world thankfully disconnected from ours, it is just as vulnerable or perhaps more. Recently the Tanzanian government cut off a piece of the park and turned it into a uranium mine. There is now talk of prospecting for oil and gas in the reserve. Men with guns continue to take lives here, and as on the other battlefields around the world, it seems very difficult to stop them.

Robert Ross’s Selous in Africa: A Long Way from Anywhere is published by Officinal Libraria and distributed by ACC Distribution.