At the National Portrait Gallery in London, not far from the ticket hall, there is a small bay for free temporary exhibitions. It can take you by surprise as you pass it in the corridor. This summer, as you walk toward it, an uncanny sight faces you—the head of a man emerging from a white cocoon, like a figure in a shroud. But the face is far from dead. In fact it is ferociously alive: it is an unfinished self-portrait by Lucian Freud.

The white sheet through which his head pokes is the canvas itself and the unnerving oval form of the emerging face is a result of Freud’s practice of beginning a portrait by focusing on a central feature—nose, mouth, forehead, a shadow on the brow—and working very slowly outward. You can see this in his incomplete portrait of Francis Bacon of 1957, abandoned when Bacon set off abroad. The self-portrait here, probably from the mid-1980s and never shown in public before, does resemble Freud’s famous Reflection (Self Portrait) (1985), but its uncanny strength gives it far more impact than you would expect from any preparatory sketch.

Freud was fond of the NPG and the gallery was proud of Freud. He’s present in the museum’s collection as a subject; the NPG possesses many photographs of Freud as well as a sculpture of him by Jacob Epstein and drawings of him by Frank Auerbach and David Hockney. And he has starred here as an artist—Britain’s greatest, strangest modern portraitist. Crowds flooded in to the exhibition “Lucian Freud Portraits,” shown in 2012, the year after he died at the age of eighty-eight. That exhibition drew more visitors than any previous NPG show, suggesting an interesting fact: this grand, obsessive easel-artist, with his charcoal sketches, his thickly daubed palette and tough hogs-hair brushes, his studio full of oily rags, had somehow eclipsed the more recent, sensation-seeking Brit Art generation, and a formidable group of installation and conceptual artists, as the nation’s enduring avant-garde art-world hero. Violent, curious, nosy, intrusive—sometimes tender—Freud’s portraits were ruthlessly observed: he was a pitiless observer of the human body, and of human vulnerability and frailty.

Freud is a powerful example of post-mortem state approval. The new self-portrait is a centrepiece for “Lucian Freud Unseen,” a small display of drawings and sketches from Freud’s voluminous notebooks. These were allocated to the Gallery under the “acceptance in lieu” scheme whereby the British government accepts objects or houses in place of inheritance tax: in this case the self-portrait alone settled tax of over half a million pounds, and the archive nearly 3 million. This fruitful, sometimes controversial scheme, started in 1910, is administered by the Arts Council, and has brought over £250 million of “cultural property” into public ownership over the past decade alone. The biggest offer so far relates to Freud’s own collection: his forty Frank Auerbach paintings and drawings—shown at the Tate in 2014—were given by his estate to settle tax of £16 million.

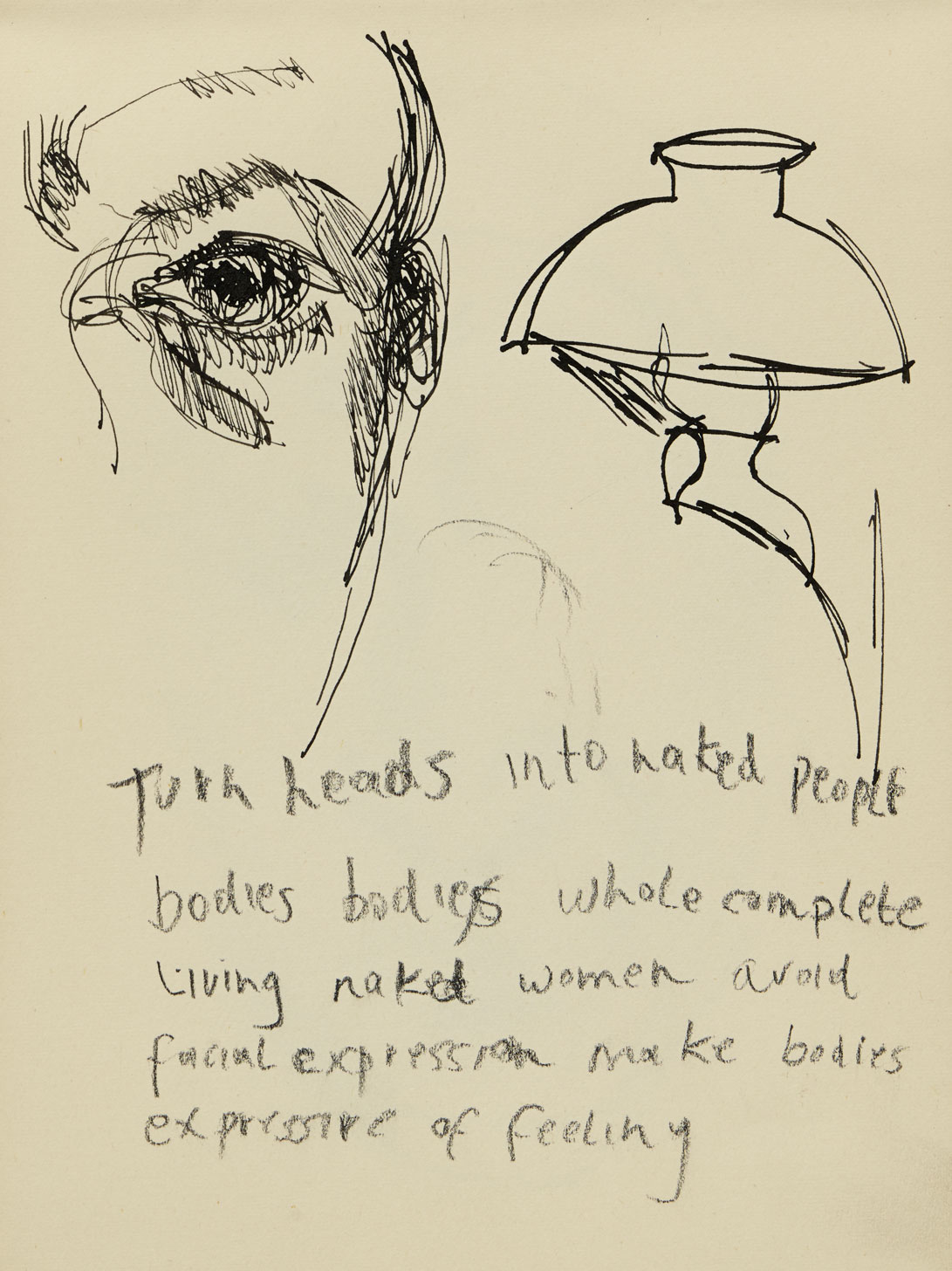

The bequest of Freud’s own work is a huge archive, with material from his early years to the 1990s: countless letters, 162 childhood drawings, and 47 sketchbooks—in all there are 800 drawings. The sketchbooks form a kind of artist’s autobiography, vivified by jottings on ideas and projects and people, phone numbers and racing tips. The National Portrait Gallery’s senior curator, Sarah Howgate, has selected many of these for a book to accompany the show, with an essay by Martin Gayford (whose 2010 book Man with a Blue Scarf gave such an unforgettable account of the perils and pains, and pleasures, of sitting for a Freud portrait). The current display is a tiny fragment of the riches. But it takes us through his life, beginning with packed, colorful childish paintings, full of birds and trees, that date from his early boyhood in Berlin. The family emigrated to London in 1933, when he was ten—five years before his grandfather Sigmund Freud fled Vienna. Lucian’s childhood works and letters were carefully dated and kept by his mother Lucie, whose controlling, protective interest he bitterly resented—he crows back at her in a teenage letter from Paris on show here, in spiky black on ragged red paper, about paint, and shirts, and lies.

Freud was always a rebel. He was expelled from his private school, Bryanston in Dorset, for “disruptive behaviour”; later, he left the Central School of Arts in London, in protest at the classical curriculum, for the East Anglian school of painting, where Cedric Morris encouraged him to paint. He stalked Soho as a youthful prodigy, dressed in fur coat and fez, drinking and gambling, and after World War II (when he briefly joined the Merchant Navy, on convoy duty) he lived in France and Greece, and then settled finally in London, abandoning early experiments in surrealism and expressionism for his own realist style.

Advertisement

The sketches swim up like notations of memory. Freud’s brilliant drawing of his second wife, Lady Caroline Blackwood, with whom he eloped in 1953, focuses on her huge, pale eyes, the eyes that slant so disturbingly as she lies in bed in his 1954 double portrait, Hotel Bedroom, with his own figure dark against the light. Another portrait of her, Girl in Bed (1952), is upstairs in the gallery—it’s strange to wander between the two. And nearly thirty years later comes a study for a detail of Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau) (1981)—his first proper studio, filled with light from skylight, window, and mirror, with the women huddled around his grandson Kai, as the pierrot. His complicated family ties lasted a lifetime, as suggested by a sketch in the exhibition made in his final years for the cover of his daughter Esther’s novel Hideous Kinky (1992).

Freud felt—in a very old-fashioned way—that his portraits somehow got to the essence, the heart of the “self.” Martin Gayford quotes him as saying he wanted a painting not to be “of” or “like” the person he painted: “I didn’t want to get just a likeness like a mimic, but to portray them, like an actor…. As far as I am concerned the paint is the person. I want it to work for me just as flesh does.” After sittings, he liked to talk to his subjects, share a meal, understand their feelings. “In a way, I don’t want the picture to come from me. I want it to come from them.” In practice, this often meant that the person did not exist for Freud apart from the sittings: those who did not turn up, or wriggled, or chattered, or were otherwise annoying, were out—no matter what they gave up to sit for him for so long.

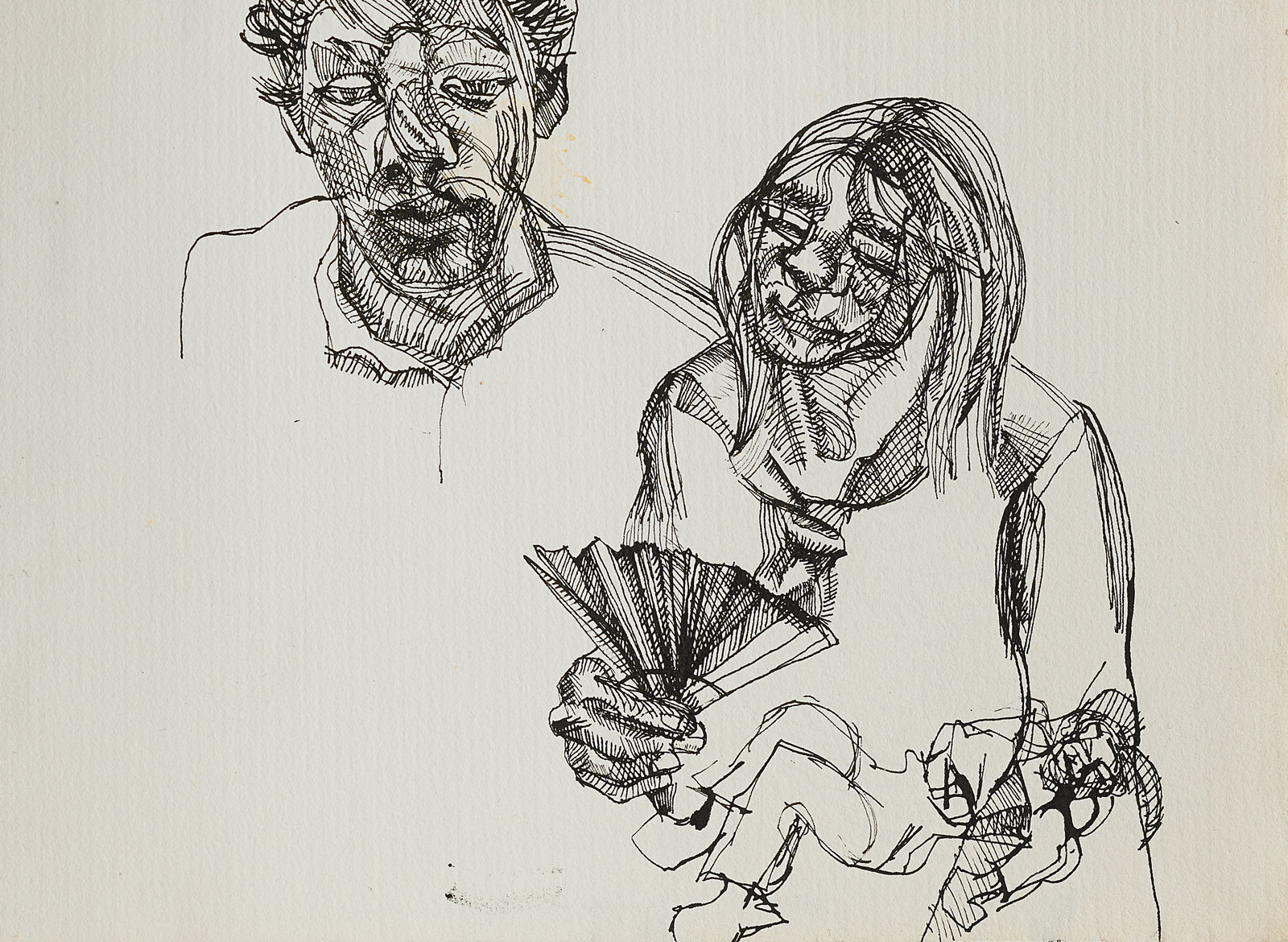

Sitting for Freud often took months while he circled around, came back, altered details, slowly filled in the center and worked outward. Small details, like the light on a lapel, a stray tuft of hair, or a deepening, swirling background, could alter the focus of the whole, and the strength and density came in part from this technique of returning, layering, reworking. The sketches were part of this work, but also a separate expression of the subject that obsessed him at the time. His lasting draughtsmanship shows in the sketch Girl sleeping, while the drastic change in his painting style in the 1950s from flat, almost hallucinatory definition, to loosely-handled watercolors and the lavish, heavy brushstrokes of later oils, is displayed in the loose, fast sketch of Anna in Venice, from the 1960s. Missing here are the naked poses that leave his subjects splayed and open, male and female genitalia rendered with a clinical gaze. But even the sketches of faces have an air of exposure, as if Freud investigates the physical being, the muscles, the clumps of hair, the slight distortion of features—noticeably so in this small display in the powerful sketch of Lord Goodman (whose portrait he etched in 1987), eyebrows twitching, jowls descending.

Looking at Freud’s sketches you feel you are in the company of a man of wit, intelligence—and who has a rather uncomfortable, even frightening power. For his sitters, vanity was out of place, affectation was punished; there is something rough, and dangerous about his work. But even in the slightest sketch, what shows through, and what lasts, is his agile talent and his penetrating, devouring curiosity about people.

“Lucian Freud Unseen” is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, through September 6. The accompanying catalog, Lucian Freud’s Sketchbooks, is published by Yale University Press.