—The Editors

Television didn’t arrive in England until the Fifties. Its images were of course in black, white, and grey, which fit perfectly with our childhood lives, already chugging along in drab monochrome. Light grey drizzle fell from the black clouds and specks of soot belched from the factory chimneys. It was grim. This monotony could only be broken by a visit to the cinema. Republic Pictures film serials and Flash Gordon were my guides to a more exciting future.

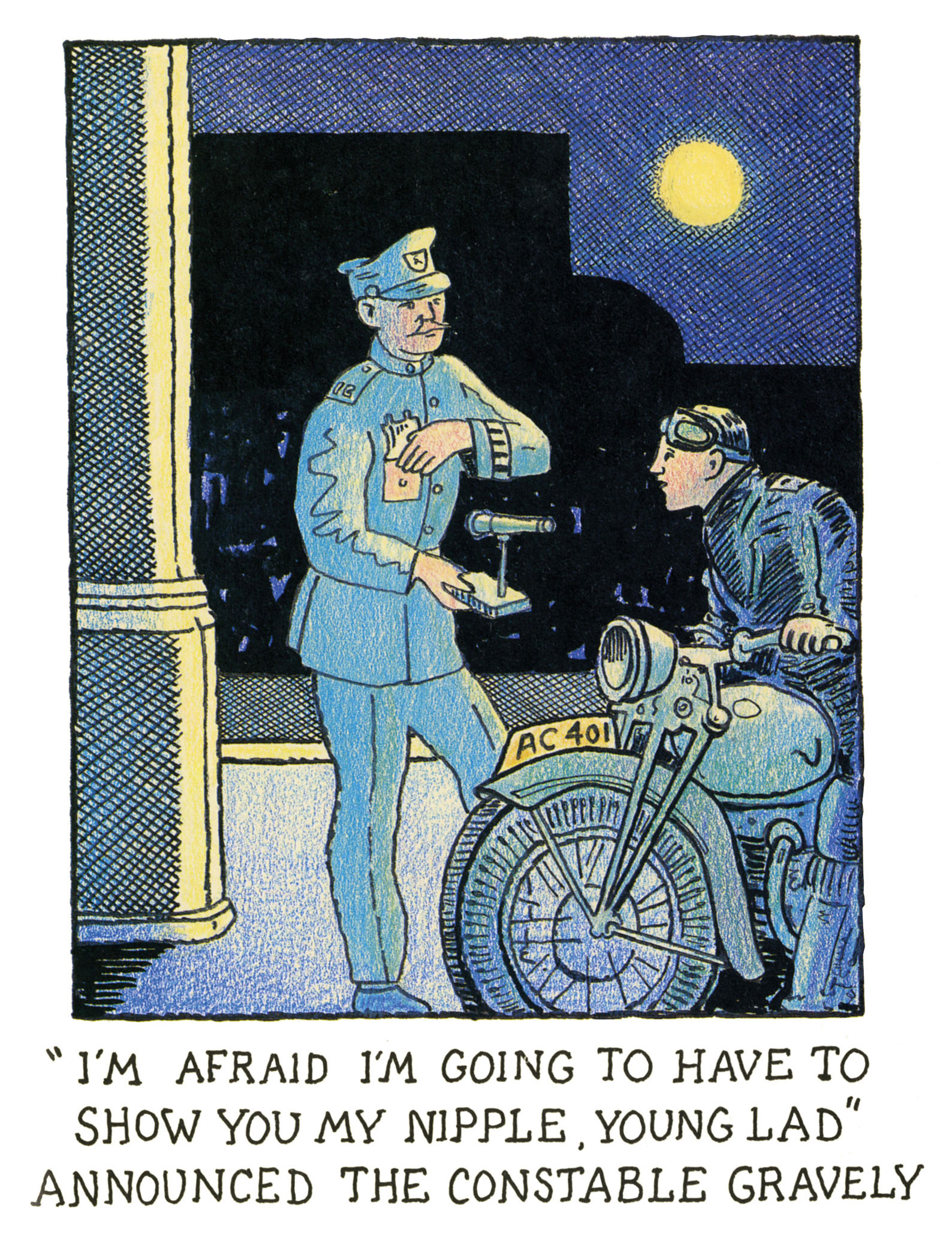

A film I remember fondly featured a scene where a tousle-haired man in a belted raincoat is leaning against a tall building in Manhattan. A cop walks by swinging his billy club. “Move along, buster!” he exhorts. “Do ya think you’re holding up the building?” The accused adjusts his battered hat and moves away as instructed. The building crashes to the ground in a flurry of dust and rubble. I had entered the world of the Marx Brothers and I would never look back.

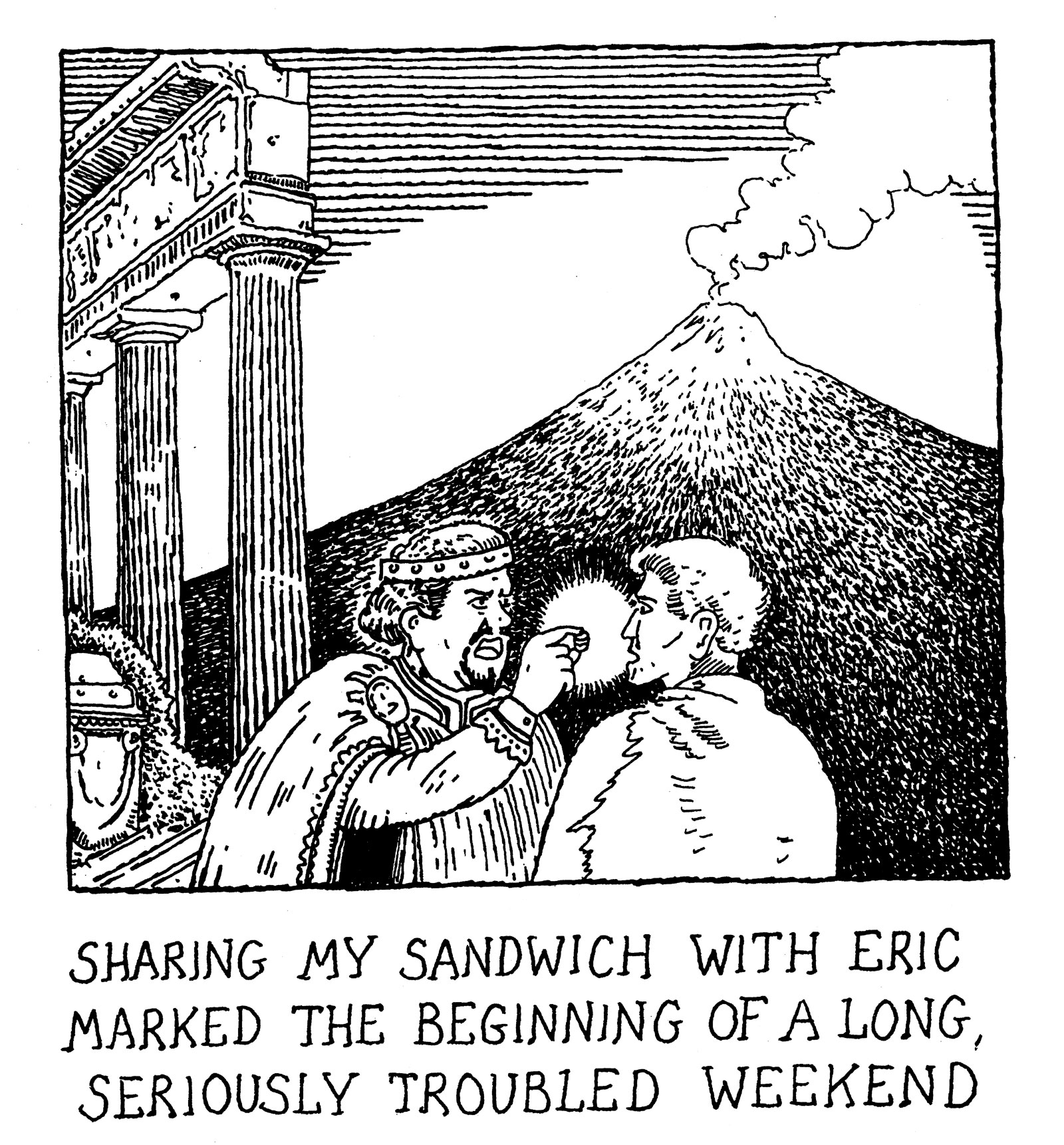

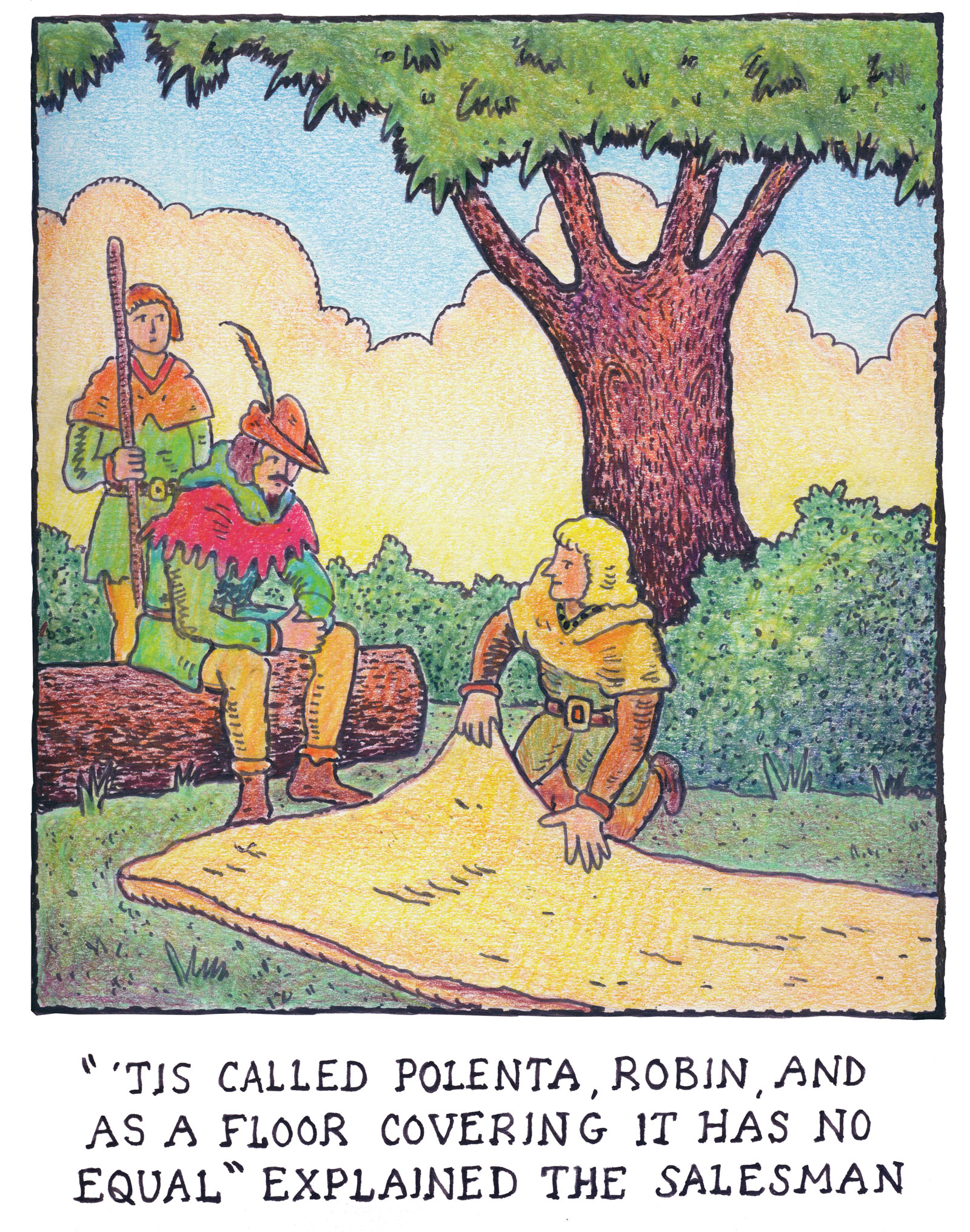

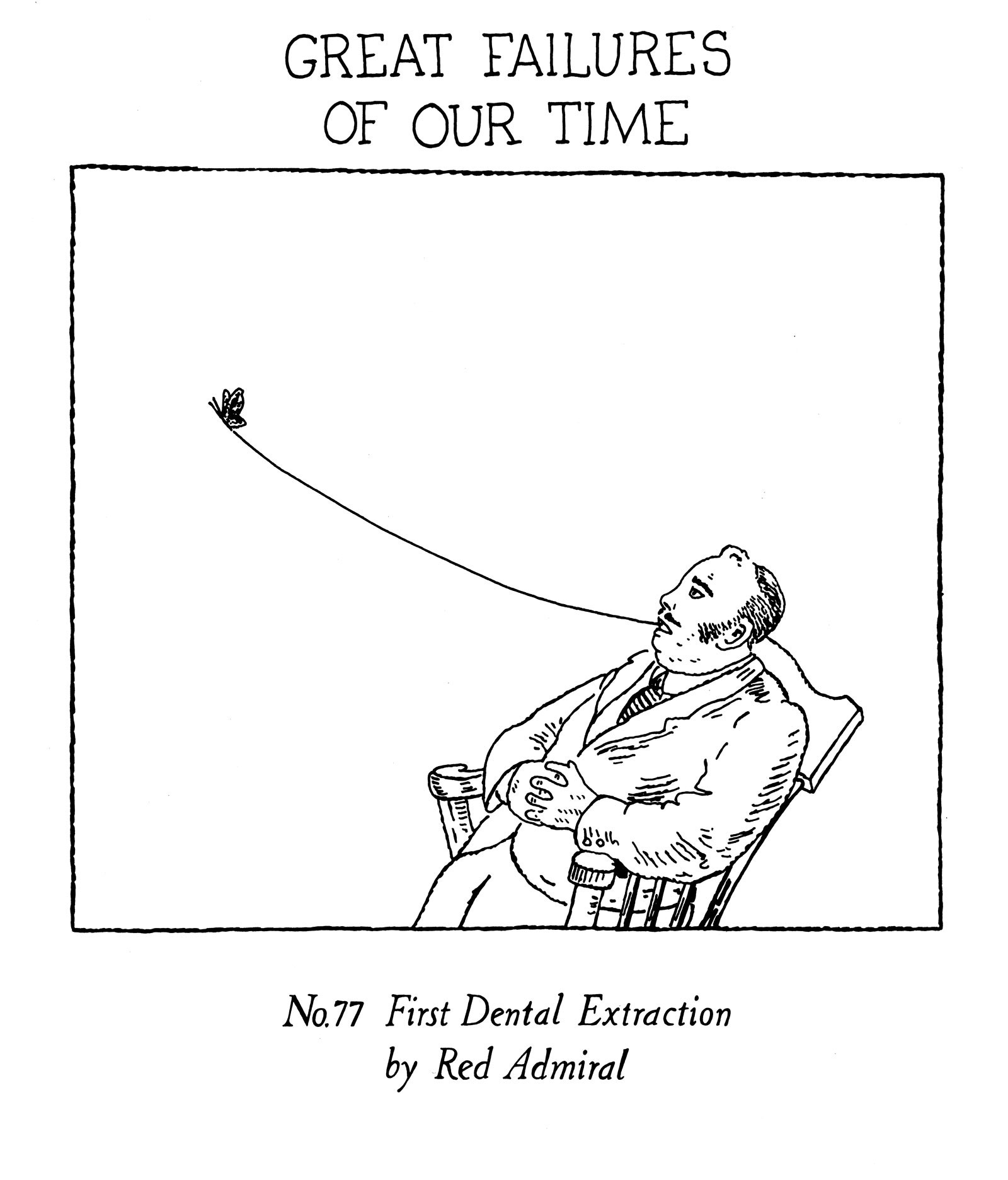

Years later at art school I came upon a similar spirit of anarchy in the work of the Dada and Surrealist poets and painters. I was home, and dry. And yet, I was distinctly out of step with the prevailing ideology. I was surrounded by abstract painters churning out fake de Koonings and Rothkos. The collage novels of Max Ernst, with their haunting dreamlike imagery and absurdity, became my beacon as I tried to escape the prevailing orthodoxy.

My early attempts at prose poetry found their way into print in the samizdat publication Adventures in Poetry, published by the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church in the Lower East Side. Encouraged by poets Ron Padgett and Larry Fagin, I came to New York and read from my collected works. After years of neglect in my homeland I had finally found my audience.

—Glen Baxter, August 2016

PAYING ATTENTION

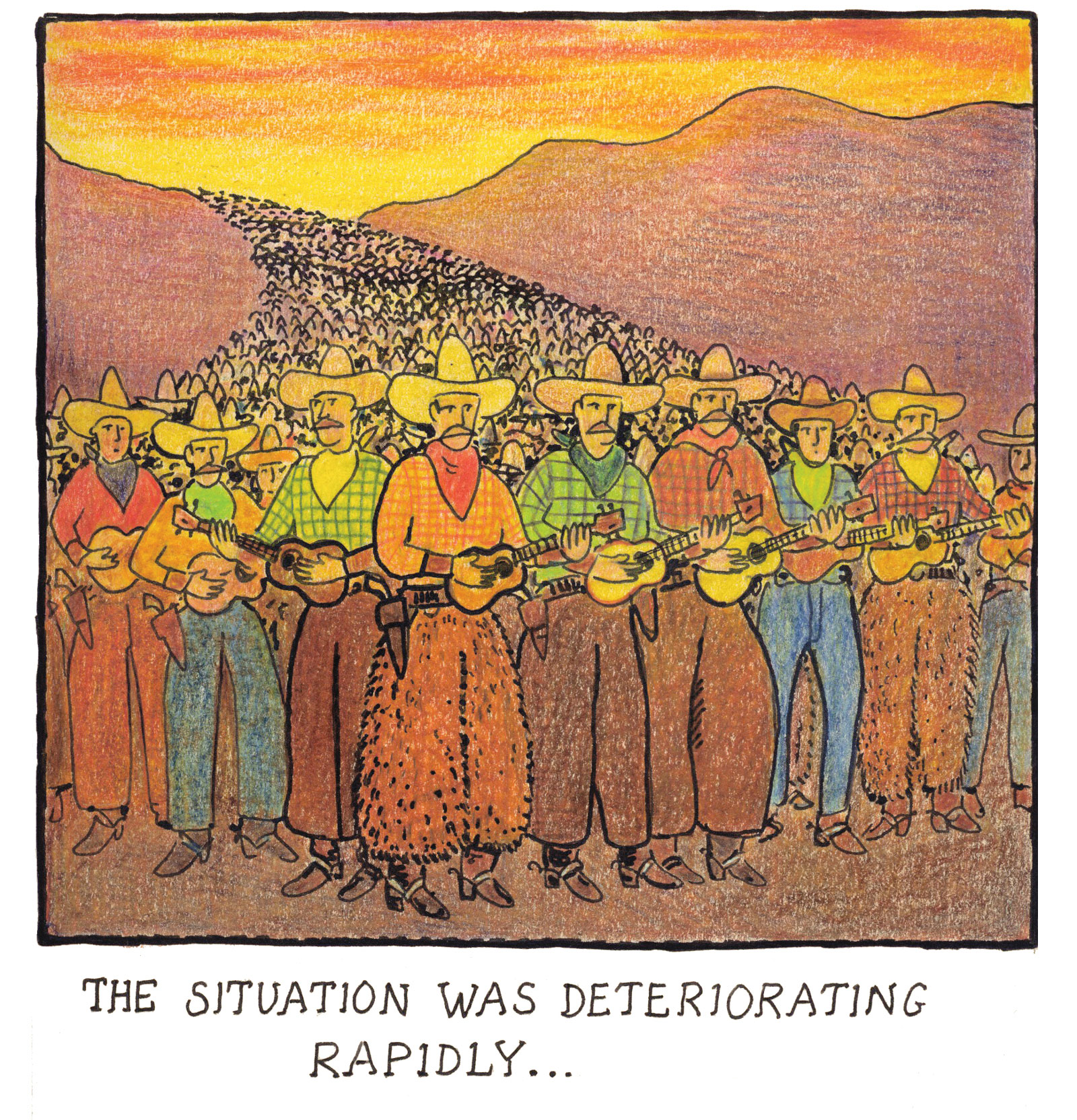

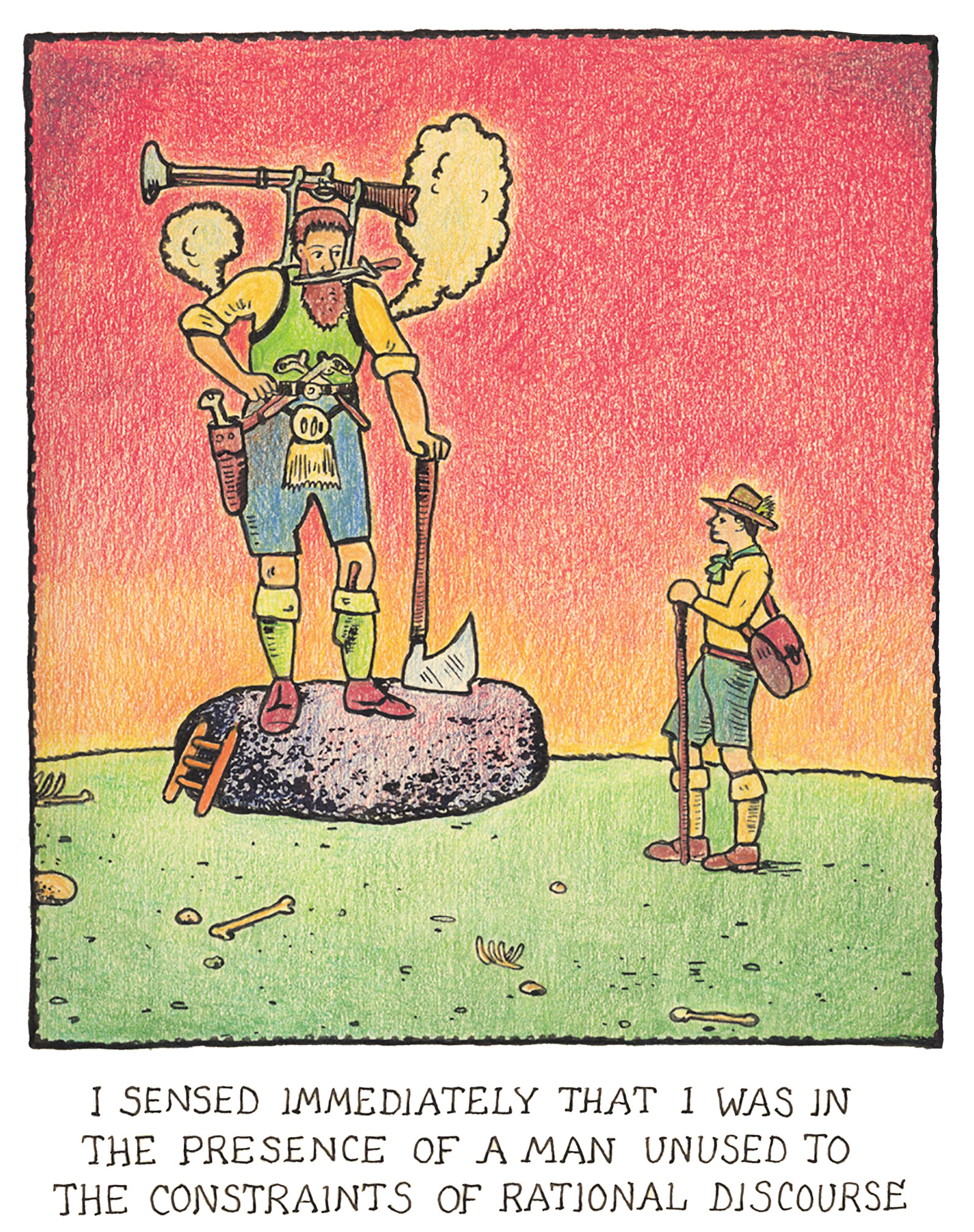

It had taken me a week to prepare for this. No one had the slightest suspicion that their tongues would be the subject of a police investigation, but there would be time enough for research and debate later. The dinghy rounded the headland with a great deal of movement. The Mate puffed greedily at his habit. It was not, after all, for him to criticize the catering at Port Moresby. At the centre of the recent upheavals and reciprocations stood a woman the like of which the islanders had not seen before. One arm longer than the other, reddish hair swept up in the breeze, she certainly commanded respect, fear, admiration, and disgust. The Mate ceased his tugging and looked at the Captain. He could not stop transforming his thoughts into a string of continuous disappointments. He pushed his forehead up and back. A plank, about seven feet long, remained inches away. He saw it twice. He had tried to reach it only once before, but that had been three weeks ago to the day, and for the moment he seemed content to remain where he stood, swaying over the liverwurst. If only he were able to reach out and take up the spatula, he might again be able to regain his composure. He knew this, but felt otherwise. His knees were rotating very slowly, and the smoke from the shore was already curling on his lower lip. He had led such a disgruntled existence that he had begun to enjoy the spectacle of a tumbler of water being filled, emptied, and filled again. A slow smile of gratification flashed into the air. It seemed to emanate from his chin, but he knew this was unlikely. He was evidently upset. He tumbled forward into a beaker of milk. This was his last chance. He grabbed his legs, and tucking them up under his collar, he rolled quietly into the harbour.

Almost Completely Baxter: New and Selected Blurtings is published by New York Review Comics.