The first time I met Jean-Michel Basquiat was in the spring of 1979, at the Mudd Club. His hair was dyed orange and cut very short with a V-shaped widow’s peak in the front. He wore a lab coat and carried a briefcase. “Going on a trip?” I asked him. “Always,” he replied. He had a disquieting stare. He had probably taken fifty drugs that night, but it was clear there was a lot more to him than that.

He was sleeping on the floors of a rotating set of NYU dorm rooms then. He had no money at all. He had recently stopped tagging as SAMO and had renamed himself MAN-MADE, although that wasn’t a tag but a signature for things he made, T-shirts and collages and these color-Xerox postcards, which he sold for a buck or two. Eventually he sold one to Henry Geldzahler and one to Andy Warhol, and his name became currency.

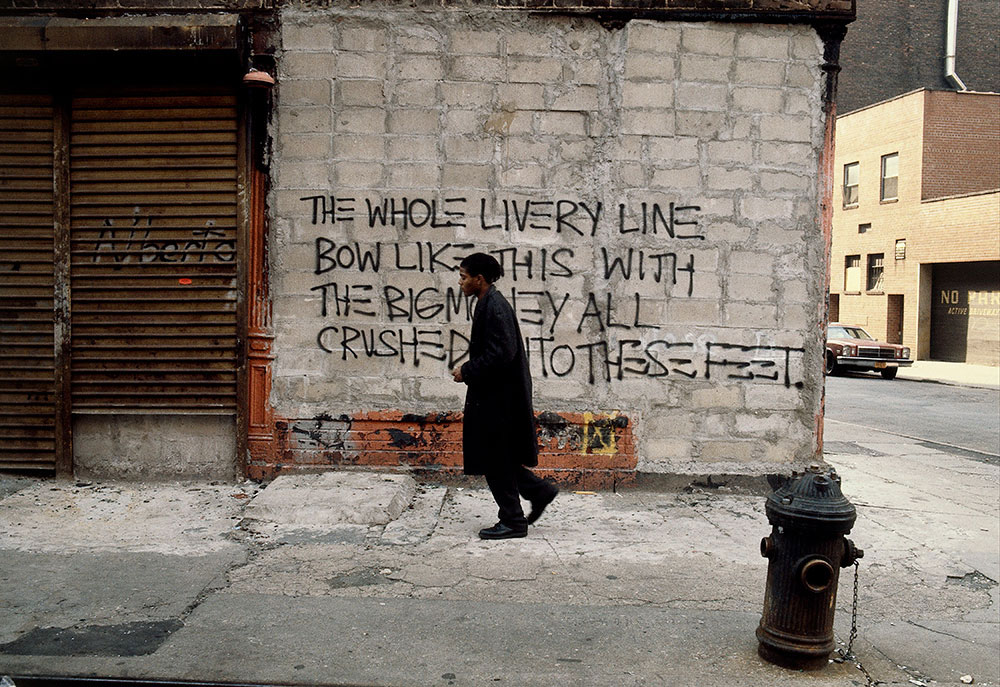

Before that, though, he was still writing on walls, but as a poet rather than a tagger. I wish I could remember more of his works than just the one someone photographed him writing on Lafayette Street near Houston: “The whole livery line/ Bow like this with/ The big money all/ Crushed into these feet.”

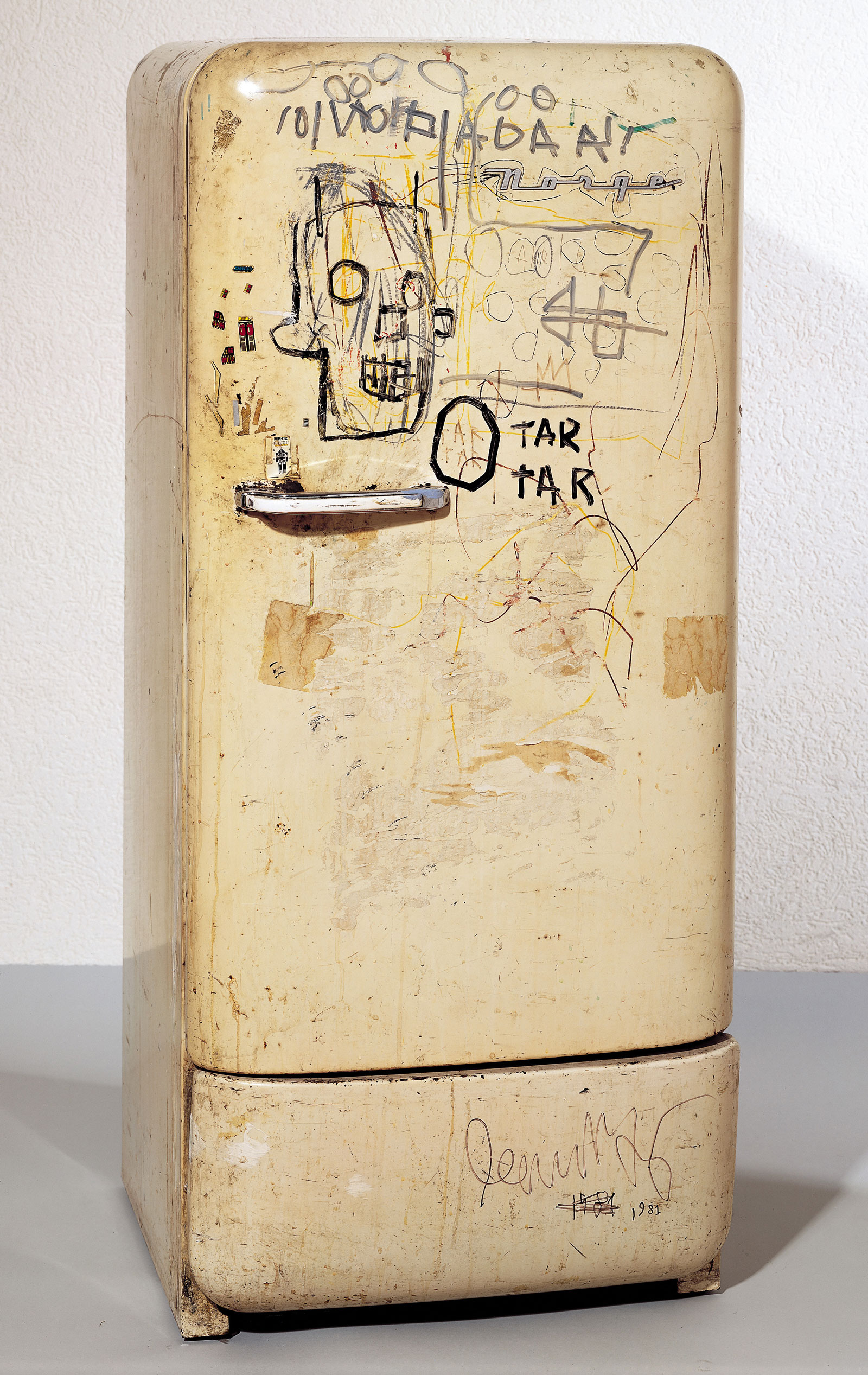

He moved in with my friend F. and ate all the cans of black-eyed peas her mom sent from Detroit, then he moved in with my friend A. and painted the refrigerator door (which she eventually sold to Bruno Bischofberger), sections of wall, a window shade, a golden coat, many other things. He also wrote “pendejo” in microscopic print somewhere near the building’s second-floor landing, and I always looked for it until the walls were repainted.

He was busy. His band Test Pattern, which after a while became Gray, played often, usually at the most obscure and unattended clubs in town. There always seemed to be about fifteen people in the crowd. For some reason tapes don’t seem to have survived—the only thing I’ve come across is a bit of feedback/noise on some compilation, which doesn’t really sound like what they did, which was somewhere on the dub/jazz continuum. He made mixtapes on which the songs are all brutally cut into and out of—a painterly use of the medium. He also made so many painted T-shirts and sweatshirts none of his friends knew what to do with them. Many if not most got thrown away.

The last time I saw Jean I was going home from work, had just passed through the turnstile at the 57th Street BMT station. We spotted each other, he at the bottom of the stairs, me at the top. As he climbed I witnessed a little silent movie. He stopped briefly at the first landing, whipped out a marker and rapidly wrote something on the wall, then went up to the second landing, where two cops emerged from a recess and collared him. I kept going.

A month later he was famous and I never saw him again. We no longer traveled in the same circles. I was happy for him, but then it became obvious he was flaming out at an alarming pace. I heard stories of misery and excess, the compass needle flying around the dial, a crash looming. When he died I mourned, but it seemed inevitable, as well as a symptom of the times, the wretched Eighties. He was a casualty in a war—a war that, by the way, continues. Years later I needed money badly and undertook to sell the Basquiat productions I own, but got no takers, since they were too early, failed to display the classic Basquiat look. I’m glad it turned out that way.

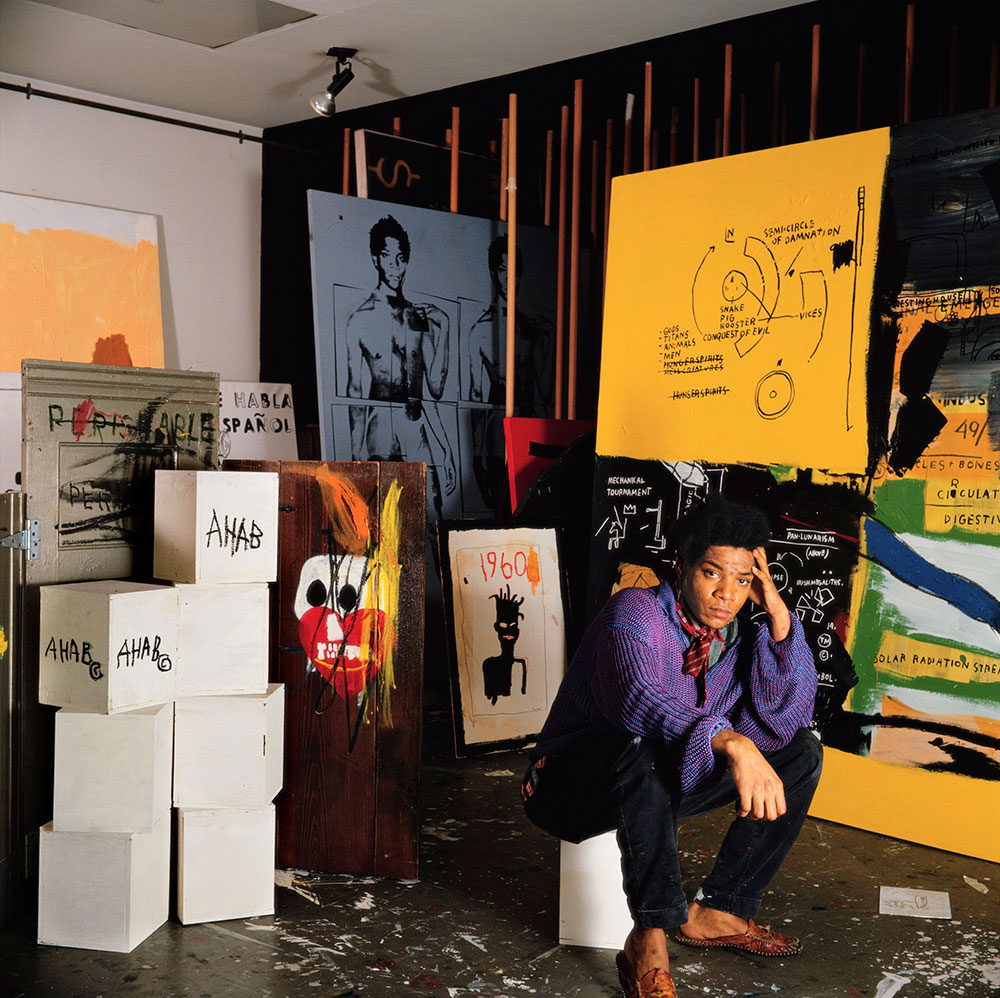

This piece first appeared in Pinakothek, Luc Sante’s visual art blog, which he maintained anonymously from 2007 to 2009. Its archives are now available at lucsante.com. The photographs of Jean-Michel Basquiat, and of Famous, are drawn from the exhibition “Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks,” now on display at the Perez Art Museum, Miami through October 16.