Is there a continuity of behavior between the stories we tell and the way we live? And if there is, does it hold at the level of the community, as well as at the level of the individual? Might we hazard the hypothesis that fiction and real behavior are mutually supporting and reinforcing?

Take the case of Italy. It’s generally agreed that one of the most distinctive features of Italian public life is factionalism, in all its various manifestations: regionalism, familism, corporativism, campanilism, or simply groups of friends who remain in close contact from infancy through to old age, often marrying, separating and remarrying among each other. Essentially, we could say that for many Italians the most important personal value is belonging, being a respected member of a group they themselves respect; just that, unfortunately, this group rarely corresponds to the overall community and is often in fierce conflict with it, or with other similar groups. So allegiance to a city, or a trade union, or to a political party, or a faction within the party, trumps solidarity with the nation, often underwriting dubious moral behavior and patently self-defeating policies. Only when fifteenth-century Florence had a powerful external enemy, Machiavelli tells us in his Florentine Histories, did its people unite, and as soon as the enemy was beaten they divided again; then any issue that arose, however marginal, would feed the violent battle between the dominant factions. This would not be an unfair description of Italian society today.

But if these observations seem commonplace, one question rarely asked is how this phenomenon is reflected in the country’s literature. Famous titles like Enrico Brizzi’s Jack Frusciante Has Left the Band, or Paolo Giordano’s The Solitude of Prime Numbers might seem eloquent in themselves; or again the fact that in Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend the two main characters are obsessed with using their writing skills to escape the Neapolitan community they grew up in and gain admission to a more worthy society. Vincenzo Latronico’s recent novel, La mentalità dell’alveare (The Honeycomb Mentality) imagines an Italy where an organization like Beppe Grillo’s Movimento 5 Stelle has taken power, an organization that originally drew inspiration from its opposition to the excesses of factionalism only to become itself a dominant faction. One of the most disturbing characteristics of the Movement, which Latronico well describes, is the way its members are frequently invited to vote online for the expulsion of others who have shown themselves in some way unworthy of the group.

But perhaps such examples are merely anecdotal. Maybe a more sensible way to start is to ask, What are the emotions and narratives typical of familism and factionalism and how have Italian authors described them? Do they simply condemn this kind of social organization, or do they rather celebrate and foster it? Or both? Perhaps it’s not the worst way of arranging life, in the end.

As soon as we start to think along these lines, the first thing that strikes us is how many Italian writers over the centuries have been exiles of one kind or another. In a society where the value of belonging is paramount, people are manically vigilant as to who is worthy of inclusion in a family, group, or community, while forced exclusion becomes a punishment that threatens to undermine the whole purpose of existence. Dante was exiled from Florence in 1302 and spent the remaining twenty years of his life seeking to get back there. Again and again the Inferno expresses the contrasting emotions of the desolation of exclusion and the joy of inclusion, the shame of being despised by one’s peers, but also the indignation in finding that one’s peers are not worthy of one’s own respect. Almost all the dead are obsessed with how friends and family back in Florence think of them, to the point that they seem more exiled than dead, more concerned with not being within a stone’s throw of the Arno than with being damned.

In general the Inferno condemns factionalism, but scholars have long since shown how the choice of those Dante criticizes and praises changes through the Commedia depending on his sense at any given time of which powerful people in Florence might be able to help him return. Toward the end of Paradiso, when it was clear that none of his politicking was going to get him home, Dante expresses the hope that it will be the “sacred poem” itself that will “overcome the cruelty that locks me out.” As with Ferrante seven hundred years later, writing is seen as a means to gain access to the desired group.

Advertisement

One reason why so many Italian writers experienced exile, and still experience exclusion of milder kinds (one thinks of the Nobel winner Dario Fo’s frequent lament that he has been excluded from Italian public television), is because they were and are themselves intensely involved in public affairs. The logic of this Italian spirit of belonging is that dominant groups always seek to enroll talented artists to their cause, while the artists themselves rarely hold back, since group participation is always the path to prestige, in Italy. From the city-states of the Renaissance to today’s world of political parties, newspapers, and Facebook, there have been few major Italian authors who have not been active in public life in some way, or who did not seek to be so.

And often it is precisely the fact that the writer is at the center of public life that leads to him being exiled. This was true of Dante and arguably of Torquato Tasso and Ugo Foscolo. Removed from his government position after the return of the previously exiled Medici family in 1512, Machiavelli went into forced retirement on his farm outside the city and wrote a book—The Prince—that he hoped would get him back into the political role he loved. The notion that took hold in England and France in the later nineteenth century that a writer should be absolutely outside public life, his art pure and at no one’s service, never really caught on in Italy.

The downside to this is that no sooner does a young Italian writer have any kind of success—one thinks of Claudio Magris in the 1980s, Enrico Brizzi in the 1990s, and more recently Roberto Saviano and Paolo Giordano—than they are signed up to write endless opinion pieces for one of the major newspapers, which of course will be deeply offended if the writer then writes for a different newspaper, since that would be a betrayal of their group. It is astonishing how many utterly ordinary articles a great poet like Eugenio Montale continued to write for Corriere della Sera long after he had any financial need.

Unsurprisingly, the very nature of literary language is influenced by this pattern of behavior, since style becomes a way of expressing a writer’s position in relation to various embattled factions. Dante insisted on writing The Divine Comedy in vernacular Tuscan, thus taking primacy away from the narrow circle of those who read and wrote in Latin, a privileged elite he was not himself born into, and always worried about being excluded from. Later, in exile, he would be astonished to discover the range of different and mutually incomprehensible dialects that existed in Italy. The vernacular was not the unifying factor he had imagined.

Nor would it be for five hundred years. In the 1840s Alessandro Manzoni complained about how irritating it was when enjoying a conversation with Milanese friends, if some outsider turned up from Naples or Venice or Florence and they all had to start speaking Italian rather than the local dialect. All immediacy of expression was lost. Yet it was Manzoni who would twice rewrite his great book The Betrothed so that it could become the model of the national language, available to everybody, and indeed, after unification in 1861, imposed on everybody by an education system desperate to achieve cultural unity throughout the peninsula. And of course being imposed it was also resented. Poetry in local dialects continues to flourish in Italy, together with novels that, like those of the Sicilian detective-story writer Andrea Camilleri, are dense with local usage. One way or another prose style in Italy always involves a gesture of allegiance and belonging, whether to an elite, a youth culture, an ideology, or a class. The only absolutely neutral and hypercorrect Italian is to be found in the country’s endless translations, mostly of American novels, that make up about 50 percent of the fiction Italians read. One is less likely to be irritated by something brought in from abroad and alien to the conflicts that galvanize Italian life. So readers can unite around a Jonathan Franzen or a Toni Morrison in a way they might not around Eco or Saviano.

The continuity of this dynamic in Italian life is extraordinary. In the Fascist period, many writers with suspect loyalties were sent into internal exile, split off from the groups that gave their lives meaning. Others supported the regime and reaped the benefits of being included in the Party. Some, like Curzio Malaparte, oscillated between the two positions, one moment in with the establishment, the next out, then in again. When you look at what novelists of the period wrote, even where it is apparently private and determinedly unpolitical, the issue of belonging is almost always central. In Natalia Ginzburg’s writing the moments of greatest pathos always come with the lonely death of someone excluded from the group, while the comedy is generated by people who find ways of forcing the group to assist them by appearing helpless and inept. Elsa Morante’s wonderful hero Arturo, in Arturo’s Island, dreams of his inclusion at a round table of noble heroes only to discover that the father he imagined as supremely worthy in fact moves in a world that is irretrievably squalid. Almost all Cesare Pavese’s novels have a protagonist drawn into involvement with a group and then suddenly withdrawing from it in disgust.

Advertisement

More recent novels update rather than change this preoccupation. Some Italian authors prefer to write and publish in groups, Wu Ming being the most famous, but Kai Zen, Mama Sabot, and Babette Factory have all joined the trend, while the Lyceum school in Milan even offers courses in collective creative writing, something hard to imagine in the Anglo-Saxon world. Interestingly, the solidarity within the group is also presented as opposition to groups outside, particularly in the media: Wu Ming, whose four, but once five, members travel together and present their work together, refuse to be photographed by the media or to appear in television. As so often, forming a group becomes a way of distinguishing oneself from other groups, in the constant Italian obsession with inclusion and exclusion. Even Elena Ferrante’s anonymity can be seen as a provocative “staying outside” in a society where being inside—known and prominent—is a priority.

In short, if Italian writers have always condemned factionalism, their work inevitably expresses the emotions, values, and stories of a world where belonging is more important than any other value, freedom, goodness, and success included. So Italy is a country where “regional insults” are now (rather absurdly) banned in football stadiums, but admired in Dante:

… Ah, Genovese, people strange to all good custom and full of all corruption, why are you not driven from the world?

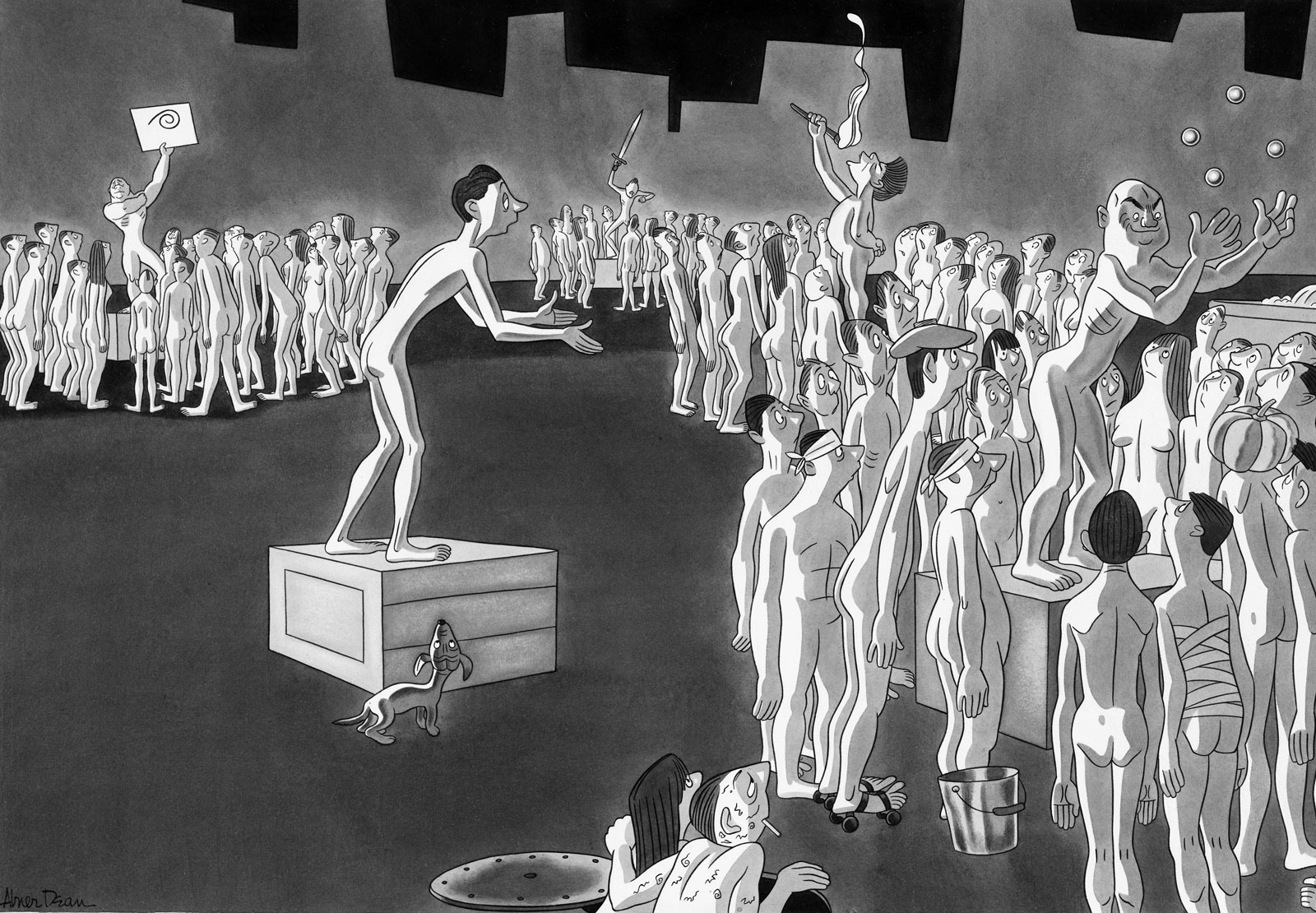

What Am I Doing Here? by Abner Dean will be published by NYR Comics October 11.