More than thirty years after her death, the oeuvre of American painter Alice Neel attracts ever greater interest, and seems only ever more relevant: the substantial and moving exhibition of her paintings currently at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague is the latest indication of this groundswell of attention, including various shows and catalogs in addition to a fine biography by Phoebe Hoban and a biographical film directed by Neel’s grandson, Andrew Neel. The current exhibition (which recently closed at Helsinki’s Finnish National Gallery and will travel next to Arles, France and from there to Hamburg, Germany) has occasioned the beautiful volume Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life.

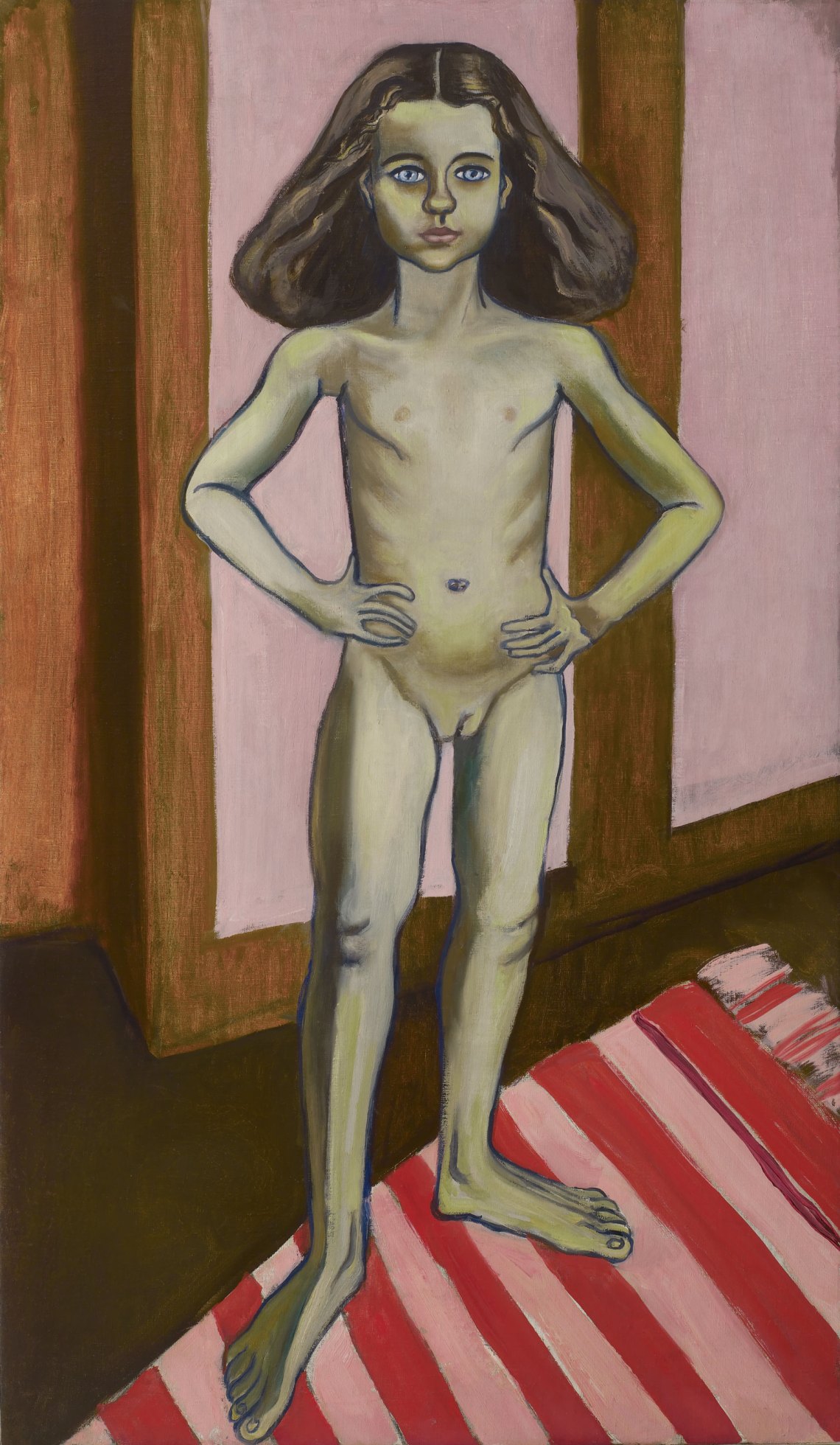

Neel’s portraits are rarely serene but always memorable. Her early paintings range from the unsettling to the disturbing. In her nude painting of her estranged daughter Isabetta (1934, repainted 1935), the prepubescent girl stands arms akimbo with one foot forward, her gaze frank but also unseeing, her child’s body frank also, but flattened and greenish, her feet peculiarly large. In the Degenerate Madonna (1930), a mother notable chiefly for the ghostly black nimbus of her hair, a mouth like a gash, and fierce elongated nipples like bloody daggers, overlooks a ghastly-grey bald infant with a skull of hydrocephalic proportions, tiny crooked features and stiff white legs like a doll’s; while the faint profile of a second bald-headed child—or the infant’s reflection—looms bodiless in the background.

Neel’s later paintings largely eschew such melodrama, but they are always uneasy, inviting the viewer into a direct and often alarming intimacy with their subjects. Awkwardness abounds, and with it sometimes dark comedy, as in Victoria and the Cat (1980), a portrait of one of Neel’s grandchildren, naked and bashful, with rounded shoulders and knock-knees, clutching to her breast an enormous grinning calico cat, its tail as luxuriant as a show horse’s. Neel’s famous naked self-portrait (1980) depicts the artist in old age, perched on a blue and white striped sofa surrounded by blocks of vital color—green, yellow, blue—calm and fearless in herself, staring at the viewer through slightly skewed glasses (her only attire), mouth firmly downturned and cheeks ruddy above the deliquescence of her aged body, a sinking galleon of pale flesh. In one powerfully knuckled greenish hand, she holds a paintbrush; in the other, drooping and veinless, a white cloth. Her right foot, bluish, splays unnaturally. But as so often with Neel’s paintings, it’s the face you are drawn back to, in this case the gaze wary but defiant, as if she looks death itself in the eye.

Jeremy Lewison, an independent curator and advisor to the Neel estate who has written extensively on her work, offers two excellent contributions to the new catalog. Lewison sees Neel’s style as articulating “a tension between the realistic and the expressive, or to put it another way, between the naturalistic and the distorted.” (Neel herself defined her stance as “a combination of realism and expressionism.”) An astute and meticulous close reader of the paintings, Lewison examines not only their composition and framing—observing, for example, the influence of photography on Neel’s work—but also the effects of her color choices and brushstrokes.

Other essays, one from each of the countries where the exhibition will be shown, persuasively illuminate a range of topics, from the indirect influence of the German school of Neue Sachlichkeit, the new objectivity movement that arose in response to expressionism, to Neel’s depictions of the human body, of eroticism and its absences, and of sexuality. Laura Stamps’s essay, “Alice Neel, a Marxist Girl on Capitalism,” traces the trajectory of Neel’s subjects from the under-privileged of Spanish Harlem to art world leaders like Frank O’Hara and Ellie Poindexter, resulting, Stamps suggests, in an oeuvre the breadth of which is Neel’s greatest achievement, a Balzacian comédie humaine of twentieth-century New York.

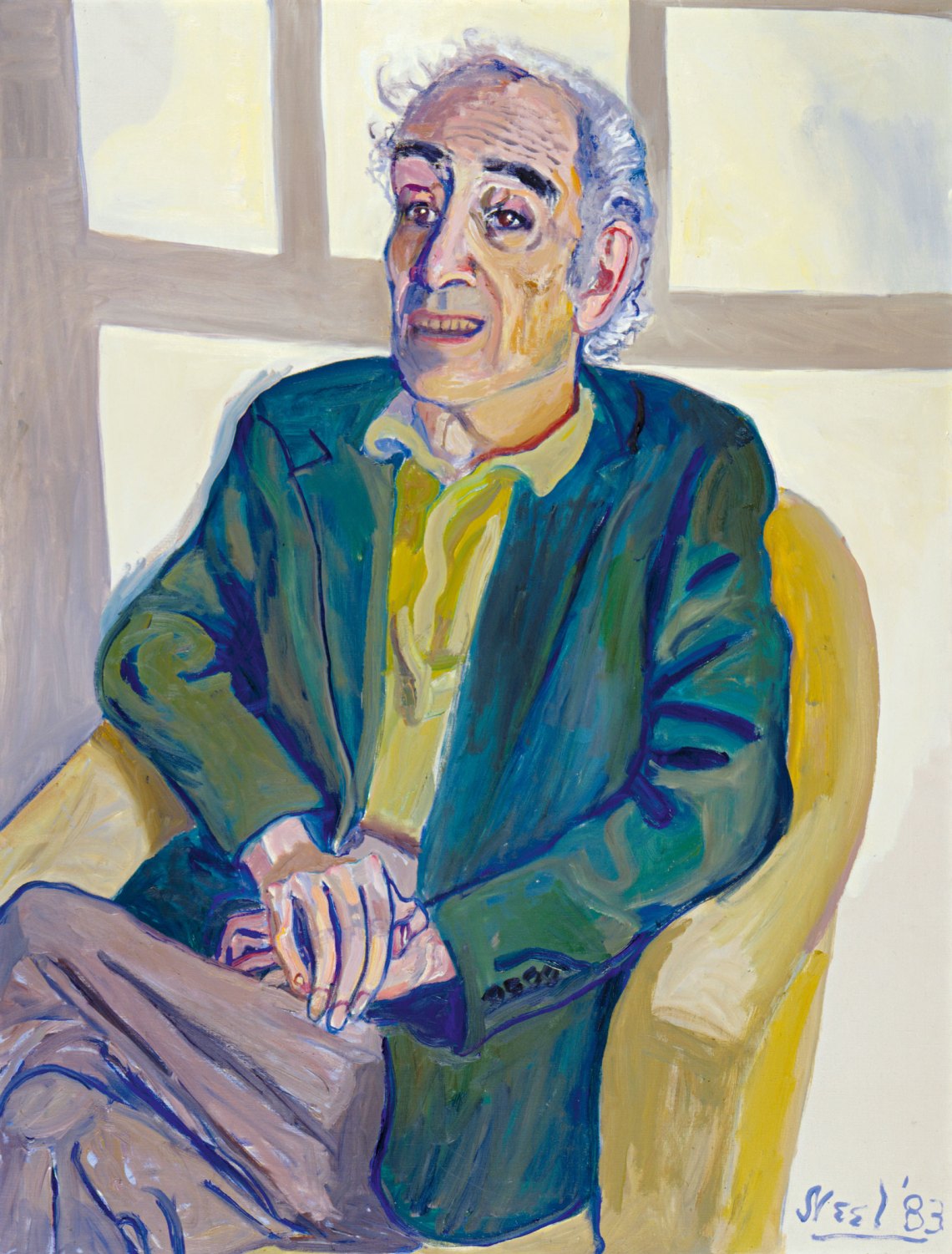

The critics repeatedly return to the intense humanity of Neel’s paintings—not in the sense of a gentle or genteel compassion, but almost its opposite: Neel’s portraits unflinchingly depict the gamut of human vulnerabilities, emotions and attitudes. Her famous 1970 painting of Andy Warhol is one example: there is no public persona to this pale and suffering man, his eyes closed to us, his sagging breasts pointing to the road map of scars across his torso (the result of a near-fatal violent attack upon him two years before). His clasped hands are small and messy; one of the knees upon which they rest remains unfinished. Warhol sits, too, upon an uncolored sofa, with only the briefest, palest wash of background. He seems to be trying as hard as he can not to be there at all.

Advertisement

Similarly, in Neel’s much earlier nude painting of her studio mate Ethel Ashton (1930), she paints—as Lewison observes—“a living, breathing being, with emotions, feelings and concerns and above all with an unidealised body.” She vividly captures “Ashton’s embarrassment and shame”: Ethel’s tiny head turns up to us in agony, all baleful eyes and long nose above her extravagantly fleshly body, with its drooping breasts and belly rolls, its rippling thighs. Where her pudenda should be is a significant black triangle—darkness—that makes her legs appear detached from her body. Everything in the painting leads the viewer’s gaze there, except Ethel’s agonized eyes that beg you not to look.

This exhilarating compendium of Neel’s oeuvre is remarkably cohesive, in spite of the diversity of Neel’s images and subjects, and of the essays included. Jeremy Lewison argues forcefully for our abiding, and indeed growing, attention to Alice Neel when he cites William Faulkner’s Nobel prize speech from 1950: “I decline to accept the end of man…. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.” Contemporary culture moves at an ever more frantic pace. Much is in flux, little seems lasting, or certain. The human soul endures, and we find both solace and challenge in its bold elucidation. Alice Neel’s life as an artist affords us an example of the soul in Faulkner’s sense; and as this book amply illustrates, so too does each of her extraordinary paintings.

Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life is published by Mercatorfonds and co-published by Yale University Press. The exhibition will be at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag in the Netherlands from November 5, 2016 through February 12, 2017, at the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles, France, from March 4 through September 17, 2017, and at the Deichtorhallen Hamburg, Germany from October 13, 2017, through January 14, 2018.