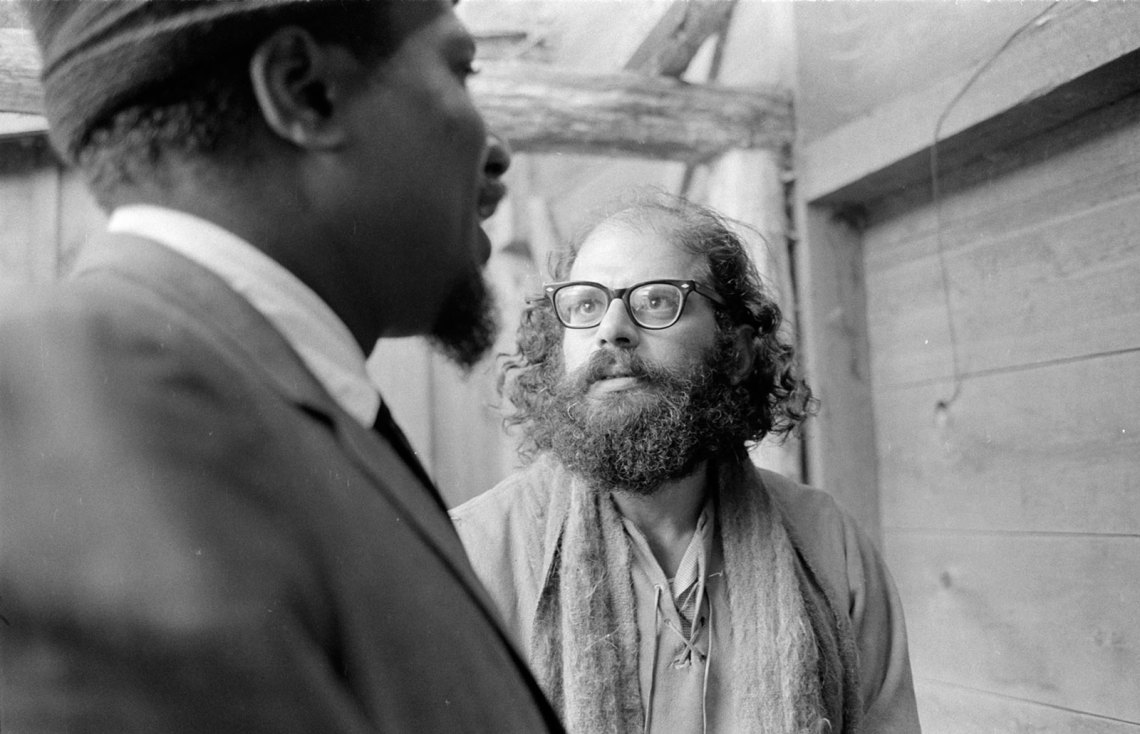

Jazz Festival is a thick book of black-and-white photographs by Jim Marshall, one of the best-known American rock photographers, who first became famous by taking pictures of jazz musicians. From 1960-1966, he photographed performers and the audiences at the Monterey and Newport jazz festivals on an assignment from Atlantic and Columbia, on whose record covers many of the faces in this book would eventually appear. For someone of my generation who saw these musicians in night clubs through clouds of cigarette smoke, seeing Pee Wee Russell in broad daylight walking his little dog or Sonny Rollins in a delicatessen getting himself a ham sandwich and pickle, as happened to me in New York, was a startling sight. I feel the same way looking at these photographs. Here are Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Hodges, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and dozens of other jazz greats representing at least four generations of musicians who made their names playing radically different kinds of music, performing or being caught by the camera schmoozing backstage between sets and enjoying each other’s company.

Marshall had no idea while snapping these pictures, of course, that he was compiling a record of a vanished world, an America even more remote from us today than the one of the rock musicians and their fans that he covered in later years. How many people younger than fifty recognize these names and those of many others in this book, and have any idea how famous they once were and what their music sounded like? Not many, I bet. The music our grandparents and parents heard every time they turned on the radio or went out to have good time, which in addition to jazz standards included hundreds of tunes written for Broadway shows, Hollywood films, and dance bands, has become unfamiliar to most of us. This is what makes looking at the faces of these musicians so haunting. They recorded so much great music only a few still listen to. Those who call jazz America’s one true original art form are not wrong.

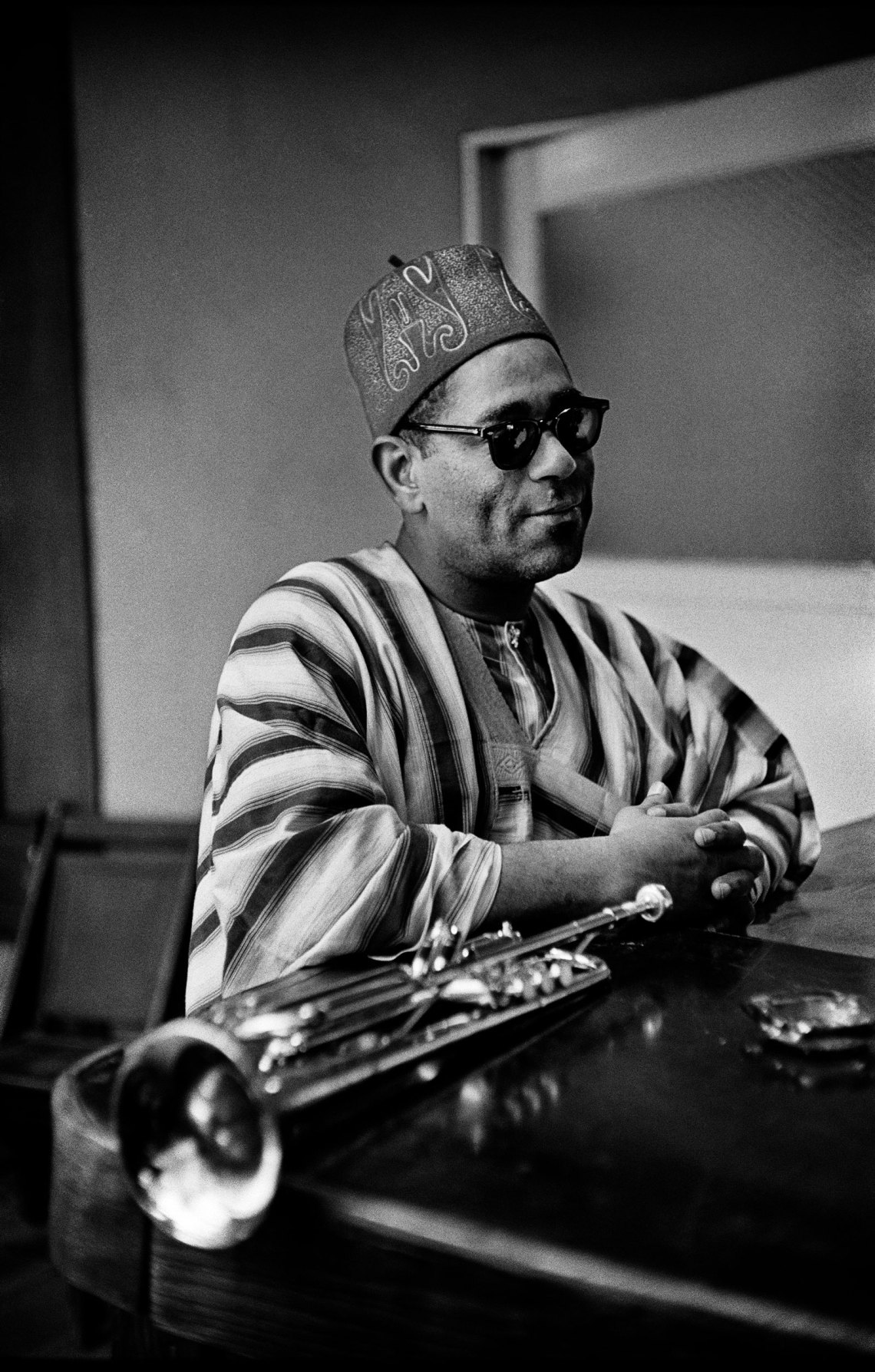

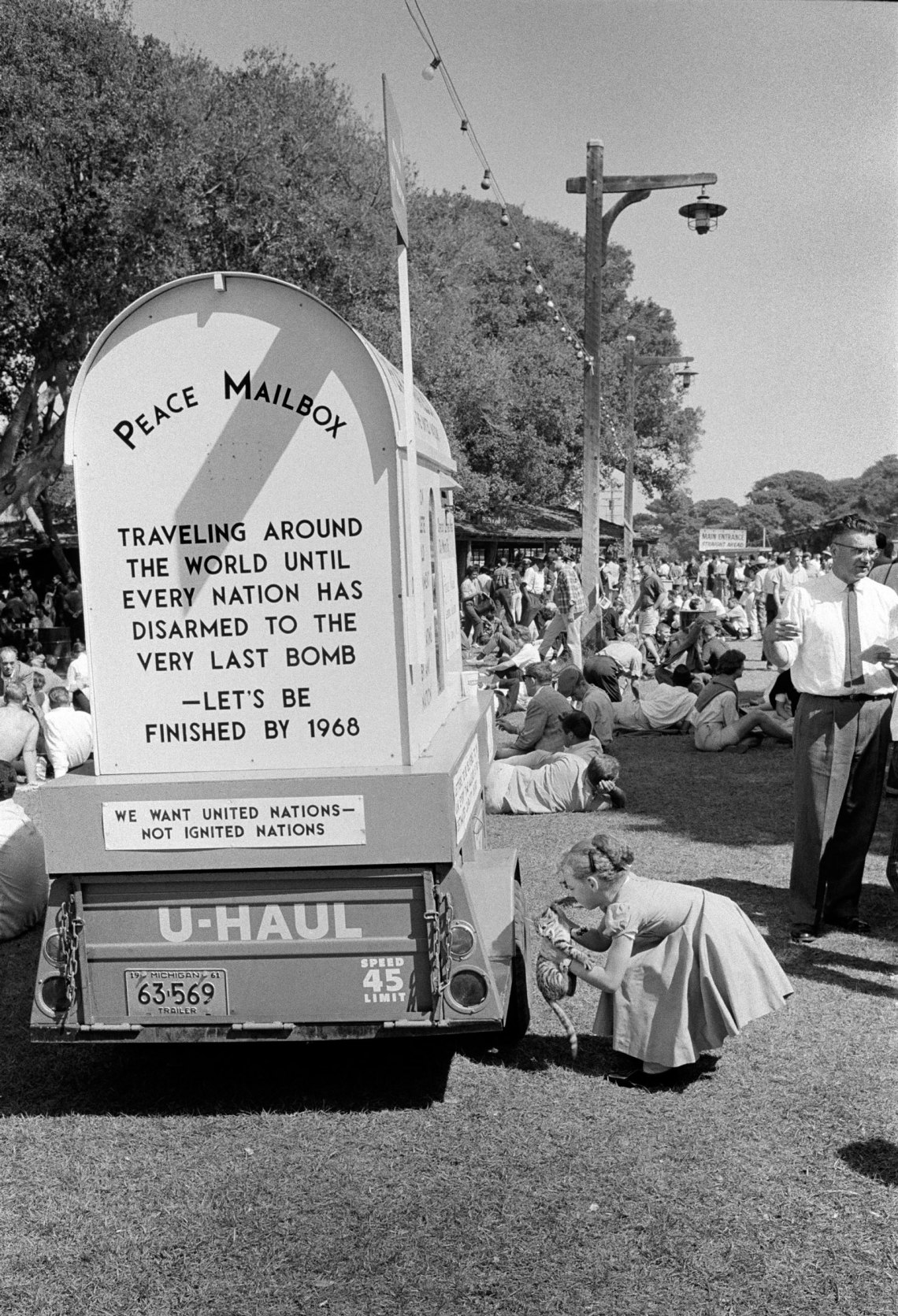

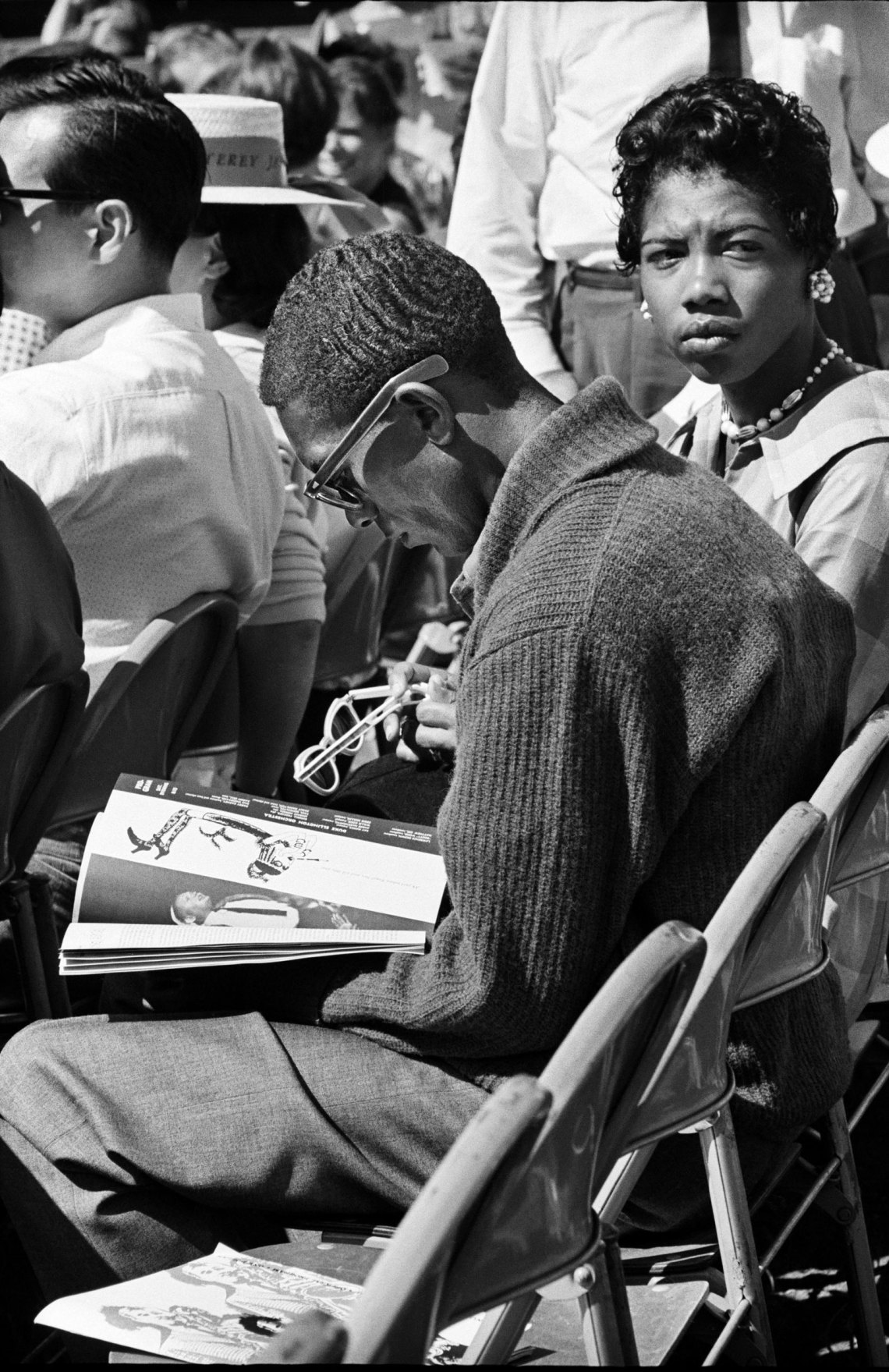

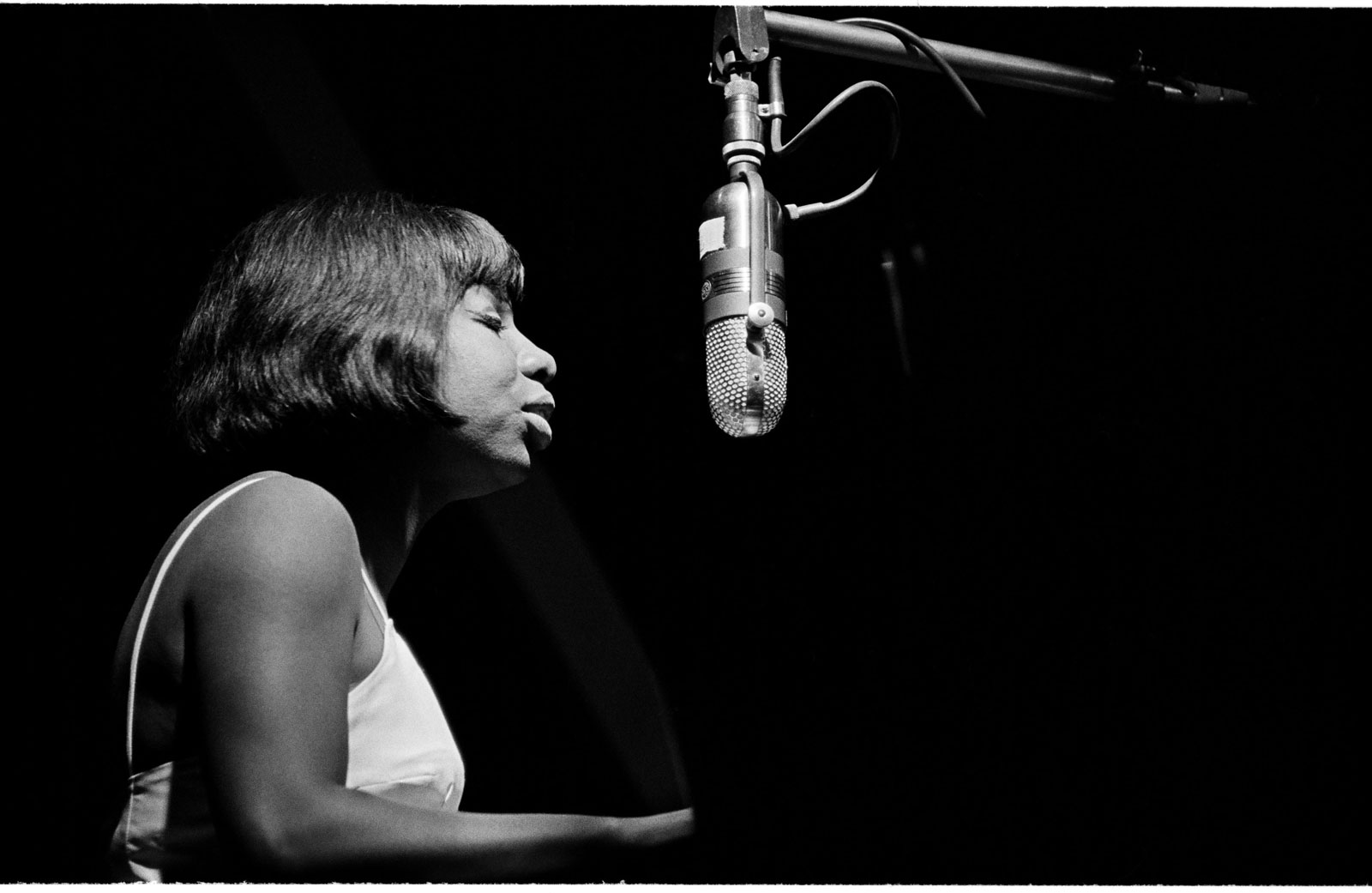

Looking at these relaxed and thoroughly integrated audiences one is liable to forget that these were the years of the civil rights movement when images on TV of bloody beatings of demonstrators by the police and the horrific scenes of dogs being unleashed on black people and their children were commonplace. There’s no hint of any tension here. Even the cops look like they are having a swell time. The musicians wear suits, white shirts, and ties, as was their custom. They’d come to gigs in the seediest of clubs as if they were going to a royal wedding or a funeral. There are exceptions, of course: Dizzy Gillespie wears a fez in one photo, a dashiki in another, a tweed overcoat and tweed cap in still another. The idea, both among the older and younger generation of musicians, was to make oneself conspicuous, either by being the best-dressed person in the room, or by breaking all the conventions.

This is true of audiences too, which interest Marshall as much as the musicians do. One rarely sees so much attention paid to one’s appearance in crowds today (though music festivals may be an exception). If there are lots of hats and dark glasses, it’s because it’s warm and sunny. It’s the individual touch with which these or some item of clothing are worn that draws our attention and makes some of the people look so elegant in these photographs. The musicians, who had to put up with drunks in noisy clubs and were often in foul mood themselves, are clearly delighted to be there and to be playing to such attentive and handsome audiences. The expressions on the faces in the crowd is one of quiet anticipation. They know this is going to be a day to remember, and you’ll agree with them once you get hold of this book.

Jim Marshall: Jazz Festival is published by Reel Art Press.