Before the blurry “photo paintings”—large images based on family snapshots or magazine ads—that would establish his preeminence, Gerhard Richter experimented with another form of Pop: cartoon drawings.

Shortly after the Berlin Wall went up and the painter defected, or as he would say “relocated,” from Dresden to the West, Richter drew a series of images featuring a single protagonist going through an abstract landscape. Recently discovered in a 1962 notebook, these have been published by his archives in a facsimile edition titled Comic Strip—a sparely beautiful book-object that, like Krazy Kat or Little Orphan Annie, has a central character or rather an expressive motif.

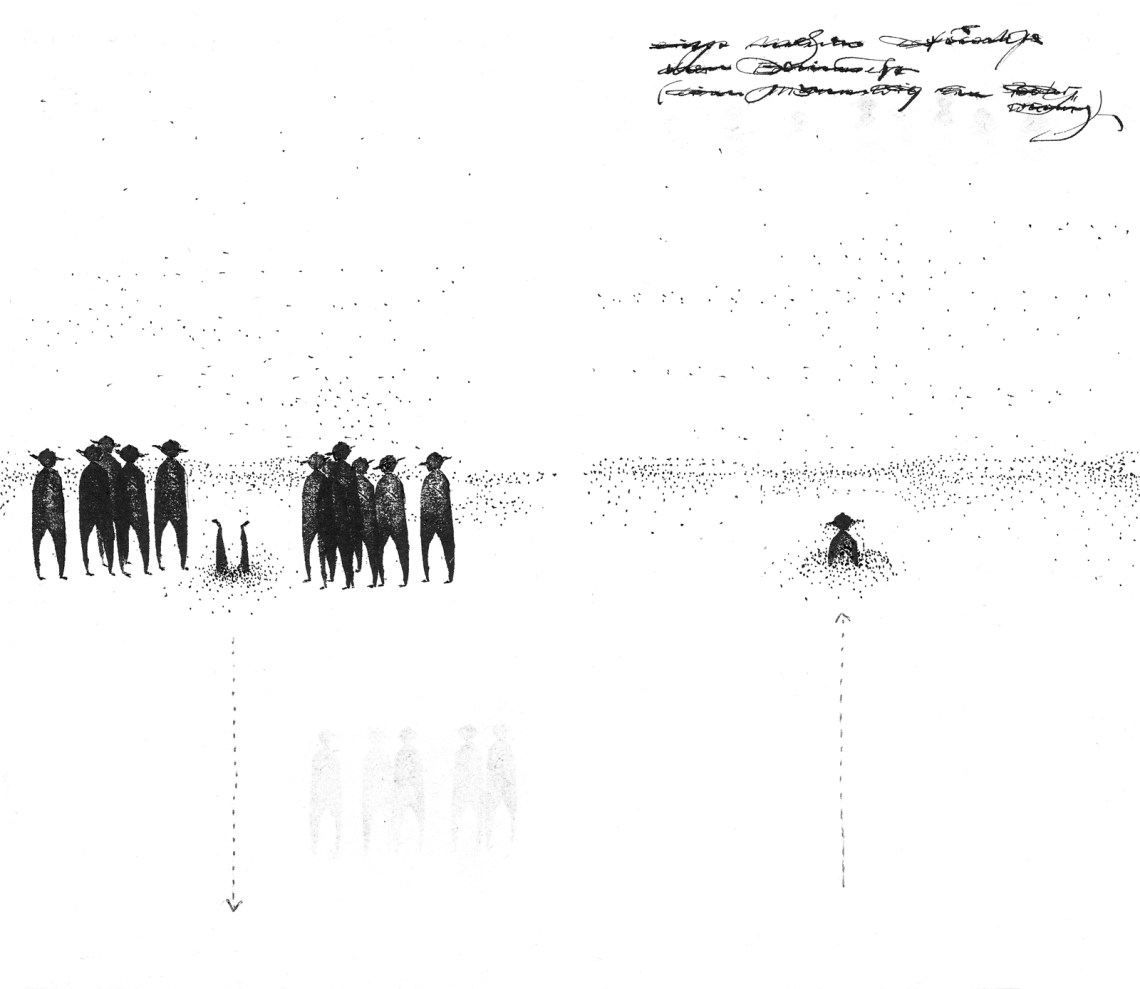

Richter’s protagonist, introduced with a cinematic serial fade-in on the book’s first two-page spread, is an armless humanoid, rendered in silhouette and distinguished, as well as gendered, by a broad-brimmed priest’s hat. In a sense, the figure relocated with Richter—he’s present, both singly and paired, in some of the thirty-one linocut abstract landscapes made by the artist in 1957. (The series was given the collective title Elbe, after the river running through his hometown.)

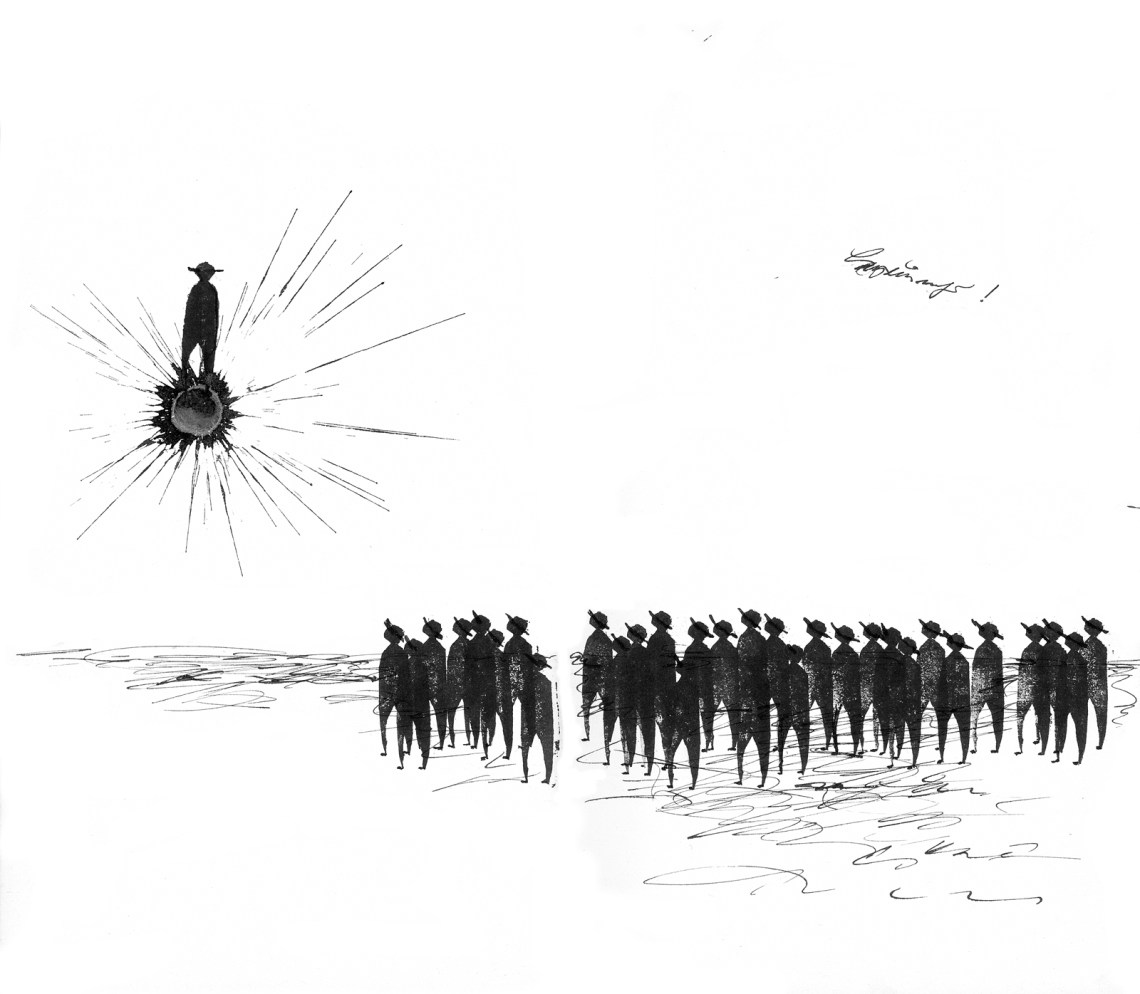

More elemental than the exaggerated two-dimensional Walking Woman that Michael Snow incorporated into his early paintings, photographs, and films, or the armless Falling Man that figured in Ernest Trova’s sculptures and paintings, Richter’s Biped Silhouette makes his way through a series of laconic, not-quite-narrative situations. Often standing alone, the Biped is a loner in a world of the replicas. (They join him a few pages in, falling from the sky—as the Weather Girls sang, “It’s Raining Men.”) The Biped faces off against his fellow stencils. He leaves the group but doesn’t go very far.

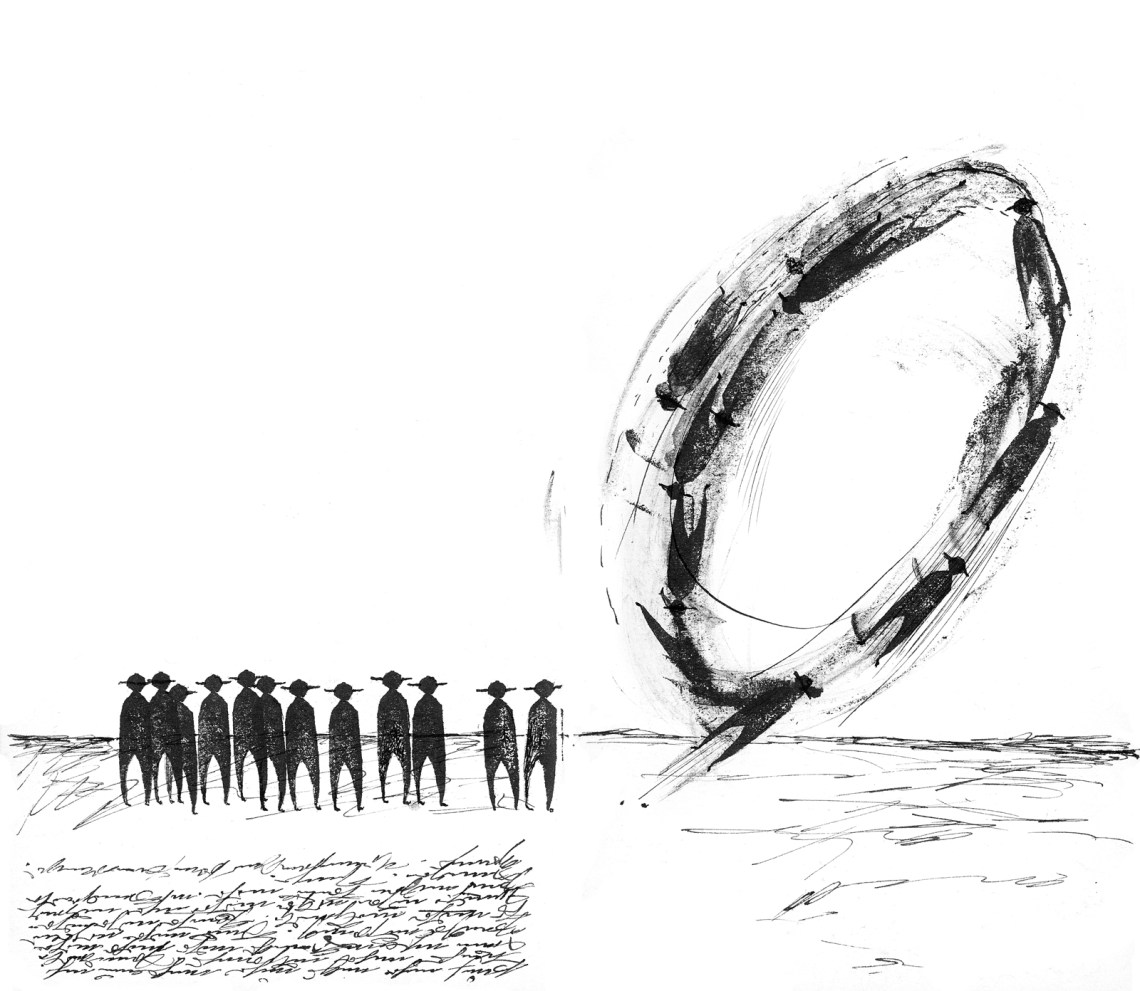

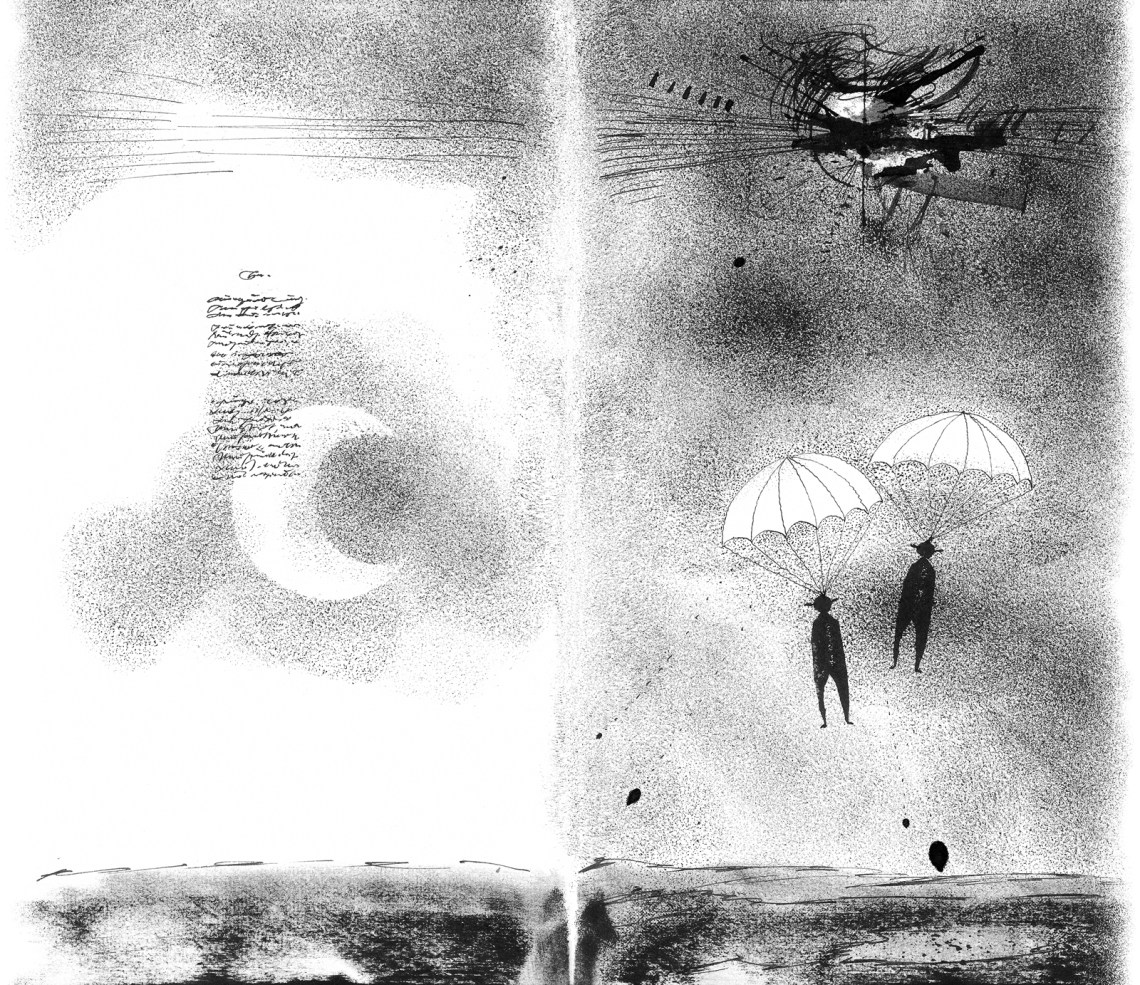

The Biped gets fenced in. He casts a shadow, is fired out of a nineteenth-century cannon, flies overhead like a bullet, does circus tricks, falls into a trap, is run over by a tank, lies on his side and gives up the ghost as replicas whizz overhead (an unmistakable sense of the bomber squadrons in formation that Richter was painting in 1963 and 1964). The Biped is put on wheels and crashes into a tree. He enters hospital and emerges with one leg amputated, blasts off… and crashes to earth.

Comic Strip’s austerely sketchy terrain is sometimes darkened by the artist’s thumb and palm prints. On other pages, Richter employs clusters of dots to suggest a desert. (The Biped dives into the sand on one page to surface in the next.) Richter’s drawings are annotated by pages or passages of elegantly blotchy, largely indecipherable writing with a family resemblance to Cy Twombly’s calligraphy; the use of ominously unreadable dialogue balloons, obscure crypto maps, and ornate official stamps suggest Saul Steinberg as another point of reference.

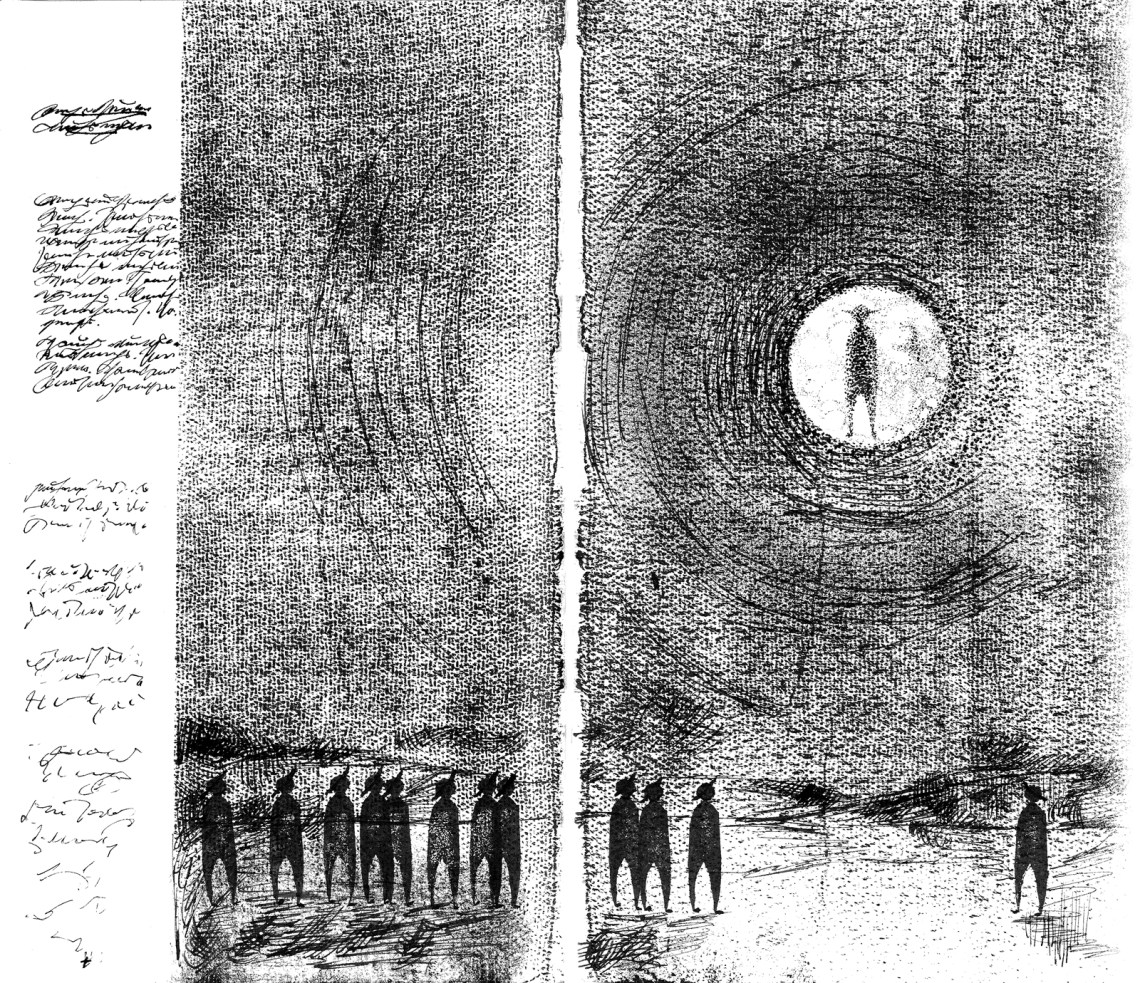

There’s a six-panel story in which the Biped plays with a child who, having demolished him, is subsequently made king. But the Biped has his moments of triumph as well—posed with a flag as his replicas march about, or walking on a tight-rope from which eight replicas are suspended upside down like pieces of laundry. On one page he stands atop an enormous pile of replica corpses. Despite an occasional partner, the Biped Silhouette is alone in the universe. (He winds up imprisoned inside the moon as his replicas look on.)

Like the anguished abstractions in Si Lewen’s wordless graphic novel, the anti-militarist “story in drawings” Parade (first published in 1957 and republished this year—another impressive, rediscovered work of book art), the Biped and his replicas are twentieth-century foot soldiers. They are mass-produced men whom Richter is pleased to have act out scenarios of existential angst, totalitarian frenzy, wartime atrocity, or space-race hubris without ever being anything more pretentious than lines on paper.

There is something Janus-like about these unexhibited drawings. On one hand, the Biped’s adventures suggest an official form of Soviet Bloc dissident art—the absurdist anti-bureaucratic animations produced in People’s Poland and Czechoslovakia during the 1950s and 1960s. On the other, in its technical virtuosity, Comic Strip looks forward to the dynamic abstract pencil drawings and paintings this fecund artist would produce in the late 1990s, a decade after the end of the cold war.

Comic Strip by Gerhard Richter is published by Walther König Verlag and distributed by Artbook DAP.