In 1972, sixteen artists were each given £1000 to produce a site-specific sculpture, to be installed in one of eight cities across England and Wales. The City Sculpture Project, which is documented in an exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, England (on view through February 19), was intended to rejuvenate public sculpture in Britain. The project sought to move sculpture out of the garden and gallery and place it on the streets of living cities, to confront the people where they lived. The people weren’t immediately convinced.

At the time, British public sculpture was predominantly found in London or fairly traditional, or both. It often took the form of monuments to the heroic war dead and the equally monumental—if rather less staid—work of Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, and Anthony Caro. Attempts to present British sculpture en plein air outside the capital—most notably in 1968, with “New British Sculpture/Bristol” and the touring show “Sculpture in a City,” which temporarily installed works in Birmingham, Liverpool, and Southampton—were sporadic. The City Sculpture works were displayed for six months, after which time local authorities or other interested parties had the right to buy them at cost. In the end, none did.

The most immediately engaging of the sculptures were unsubtle, playful things. They celebrated modern materials—fiberglass and steel rather than the bronze and stone of traditional public sculpture. “The impact of a sculpture in the city should be instantaneous, on a blatant and obvious level,” wrote artist Luise Kimme in an essay about her work for Studio International. “It should be obtrusive so as to capture the attention of the passing public.” Kimme’s Untitled (Elephant and Castle) was itself gloriously obtrusive: a huge red and blue fiberglass blob with five grasping tendrils bursting out from the wall of the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle like the proboscis of some alien creature.

One of the few original works to survive the intervening years (most have been lost or destroyed—the exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute consists mainly of plans, photographs, and maquettes) is Nicholas Monro’s equally blatant King Kong, a huge fiberglass gorilla originally installed outside the Bull Ring, a Brutalist shopping center in Birmingham. It now stands—face grimacing, arms stretched in welcome—outside the Henry Moore Institute. Like Kimme, Monro thought obviousness was what the people wanted. “In this case they will like him won’t they?” he said at the time. “Because they can understand it and appreciate it. He’s a giant gorilla.”

Monro was only half right. Though children enjoyed playing on King Kong, and a pair of disgruntled builders climbed it as part of a protest for better compensation and working conditions a few months after it was installed (placing a trowel in its hand and a hardhat on its head), the public didn’t seem to warm to it particularly. At the end of the six months there was a half-hearted campaign and public collection to keep King Kong in Birmingham, but only one person, a crossing guard named Nellie Shannon, gave any money to the cause. Her £1 donation was later returned.

Indeed, the main responses to the City Sculpture Project seem to have been indifference and barely concealed philistinism. Sculptor Liliane Lijn, whose White Koan—a tall pyramidal structure with smooth white walls, illuminated by bands of neon at night—was installed in Plymouth, found herself “disconcerted by the total lack of contact between the artist and the general public.” She had intended the work to be a jarring, somewhat intrusive presence, drawing attention to the “unreality” of the city around it, but it was accepted with barely a murmur. John Panting’s cerebral Work for the North Cross Roundabout, a pair of hovering steel stubs intersecting above a pedestrian crossing, was greeted with outright bafflement. Panting was defiant: what he called the “problem of public sculpture” (the problem being that the public didn’t seem to like it very much) was, he said, “largely with the public—not with sculpture.”

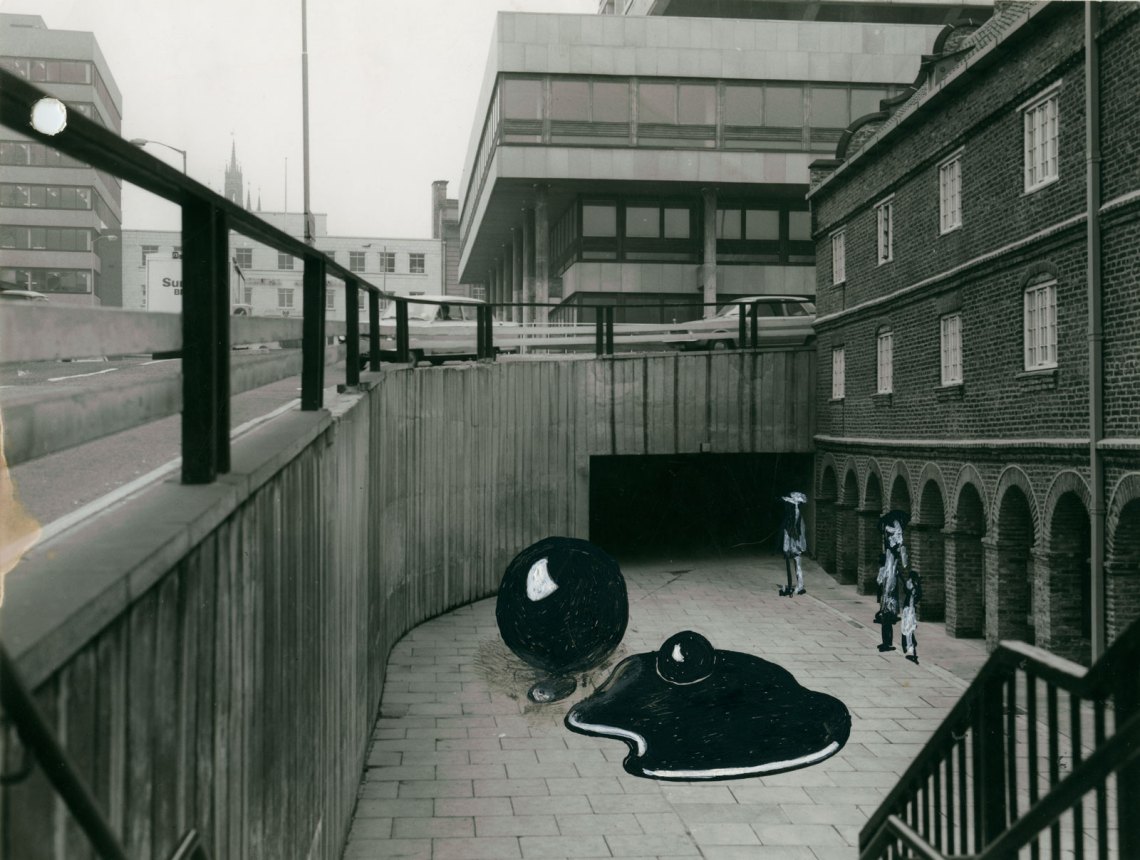

The loss of most of the original City Sculpture commissions is a shame, as the exhibition doesn’t really convey what must have been their real point: their unsettling, provoking, or glorious real-world presence. Nor do we get much of a sense of how they interacted with their environments, what it might have been like to walk close to them, to touch them, or to climb them. Many of the sculptures were located in modern, redeveloped areas: Kenneth Martin’s Sheffield Construction, 1972, a rigid tower of nineteen blue boxes, stood alongside a concrete flyover in Sheffield; Robert Carruthers’s Timber Framed Complex, a series of wooden constructions which was part stylized pagoda, part children’s playground, peeped out from the middle of a traffic intersection in Colmore Circus in Birmingham. Many of these were works designed to sit alongside—indeed to draw attention to or contrast with—Britain’s equally contentious post-war architecture.

But the records of the public responses are fascinating—if slightly depressing—in themselves. “Now, what’s all this then?” read the headline in the South Wales Echo announcing the installation of Garth Evans’s Work For The Hayes in a street in Cardiff. Evans said subsequently that his sculpture—a black bar connecting two geometric blocks, like a huge dumbbell made of steel—was made to commemorate the victims of the 1913 Senghenydd mining disaster in which 440 men had died, but this wasn’t made clear to the people of Cardiff, who on the whole found the work cold and meaningless. The day after the piece was installed Evans went out with a tape recorder and asked people what they thought of it. A scrap dealer told him he admired the craftsmanship of the piece, but most of the voices were bewildered, suspicious, even angry: “What is it supposed to represent? Total waste of time, total waste of ratepayers’ money. And the welding’s no good either.”

“City Sculpture Projects 1972” is at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, England, through February 19.