In the long history of misinformation, the current outbreak of fake news has already secured a special place, with the president’s personal adviser, Kellyanne Conway, going so far as to invent a Kentucky massacre in order to defend a ban on travelers from seven Muslim countries. But the concoction of alternative facts is hardly rare, and the equivalent of today’s poisonous, bite-size texts and tweets can be found in most periods of history, going back to the ancients.

Procopius, the Byzantine historian of the sixth century AD churned out dubious information, known as Anecdota, which he kept secret until his death, in order to smear the reputation of the Emperor Justinian after lionizing the emperor in his official histories. Pietro Aretino tried to manipulate the pontifical election of 1522 by writing wicked sonnets about all the candidates (except the favorite of his Medici patrons) and pasting them for the public to admire on the bust of a figure known as Pasquino near the Piazza Navona in Rome. The “pasquinade” then developed into a common genre of diffusing nasty news, most of it fake, about public figures.

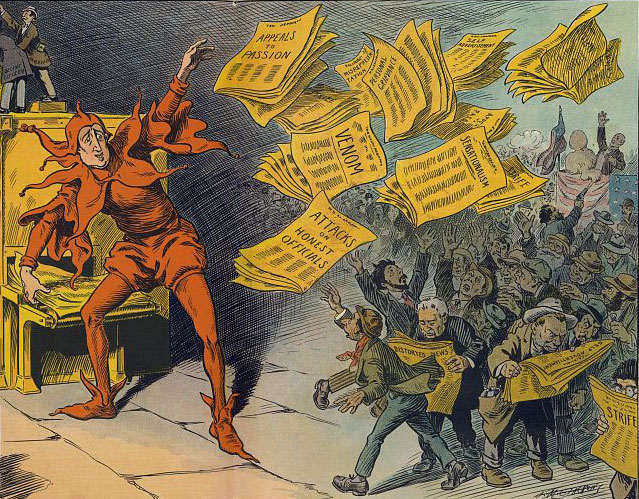

Although pasquinades never disappeared, they were succeeded in the seventeenth century by a more popular genre, the “canard,” a version of fake news that was hawked in the streets of Paris for the next two hundred years. Canards were printed broadsides, sometimes set off with an engraving designed to appeal to the credulous. A best-seller from the 1780s announced the capture of a monster in Chile that was supposedly being shipped to Spain. It had the head of a Fury, wings like a bat, a gigantic body covered in scales, and a dragon-like tail. During the French Revolution, the engravers inserted the face of Marie-Antoinette on the old copper plates, and the canard took on new life, this time as intentionally fake political propaganda. Although its impact cannot be measured, it certainly contributed to the pathological hatred of the queen, which led to her execution on October 16, 1793.

The Canard enchainé, a Parisian journal that specializes in political scoops, evokes this tradition in its title, which could be translated figuratively as “No Fake News.” Last week it broke a story about the wife of François Fillon, the candidate of the center-right who had been the favorite in the current presidential election campaign. Madame Fillon, “Penelope” in all the newspapers, reportedly received an enormous government salary over many years for serving as her husband’s “parliamentary assistant.” Although Fillon did not denounce the story as a canard—he admits hiring his wife and says there was nothing illegal about it—“Penelope Gate” has pushed Donald Trump off the front pages and may ruin Fillon’s shot at the presidency, possibly to the benefit of France’s own, Trump-like, far-right party, the National Front.

The production of fake, semi-false, and true but compromising snippets of news reached a peak in eighteenth-century London, when newspapers began to circulate among a broad public. In 1788, London had ten dailies, eight tri-weeklies, and nine weekly newspapers, and their stories usually consisted of only a paragraph. “Paragraph men” picked up gossip in coffee houses, scribbled a few sentences on a scrap of paper, and turned in the text to printer-publishers, who often set it in the next available space of a column of type on a composing stone. Some paragraph men received payment; some contented themselves with manipulating public opinion for or against a public figure, a play, or a book.

In 1772 the Reverend Henry Bate (he was chaplain to Lord Lyttleton) founded The Morning Post, a newspaper that piled paragraph upon paragraph, each one a separate snippet of news, much of it fake. On December 13, 1784, for example, The Morning Post ran a paragraph about a gigolo serving Marie-Antoinette:

The Gallic Queen is partial to the English. In fact, the majority of her favorites are of this country; but no one has been so notoriously supported by her as Mr. W—-. Though this gentleman’s purse was known to be dérangé when he went to Paris, yet he has ever since lived there in the first style of elegance, taste and fashion. His carriages, his liveries, his table have all been upheld with the utmost expense and splendor.

Bate, who came to be known as “Reverend Bruiser,” went on to found a rival scandal sheet, The Morning Herald, while The Morning Post hired a still nastier editor, also a chaplain, Reverend William Jackson, known as “Dr. Viper” for “the extreme and unexampled virulence of his invectives…in that species of writing known as paragraphs.” The two men of the cloth, Reverend Bruiser and Dr. Viper, slugged it out in their newspapers, setting a standard for scandal that makes the Murdoch press look mild.

Advertisement

News of this sort—indeed, of most sorts—could not be published in France before 1789, but it traveled by word of mouth and underground gazettes, thanks to nouvellistes who fulfilled the same function as paragraph men. They picked up “news” from places where gossips gathered, such as certain benches in the Tuileries Gardens and the “Tree of Cracow” in the garden of the Palais Royal. Then, sometimes for the sheer pleasure of transmitting information, they scribbled the latest items on bits of paper, which they traded among themselves in cafés or (lacking the Internet) left on benches for others to discover.

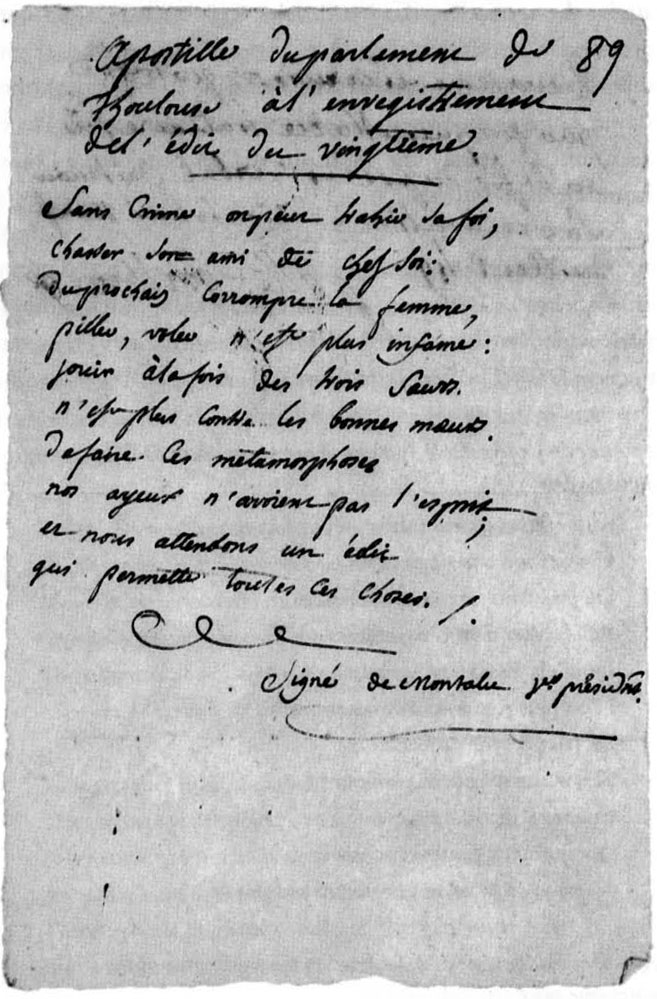

The police did their best to repress the nouvellistes, although the demand for inside information about the secret ways of les grands (the great) kept attracting new, self-appointed “reporters.” When hauled off to the Bastille, nouvellistes were always frisked, and notes were sometimes discovered in the pockets of their waistcoats. I have found some examples of this incriminating evidence in the Bastille archives—crumpled scraps of paper covered with scribbling, testimony to a primitive variety of journalism two centuries before smart phones.

The police especially hunted out the semi-professionals who combined items, usually no longer than a paragraph, into manuscript gazettes known as “nouvelles à la main.” Some of these underground newspapers made it into print. Thus a typical entry from La Chronique scandaleuse:

The duke of…surprised his wife in the arms of his son’s tutor. She said to him with the impudence of a courtier, ‘Why weren’t you there, Monsieur? When I don’t have my squire, I take the arm of my lackey.’

One of the best-sellers in this genre was Le Gazetier cuirassé (The Iron-Plated Gazeteer) which was produced in London and probably was inspired by the scandalous London press, although its news was all French. A typical item was a one-sentence paragraph: “It is reported that the curé of Saint Eustache was surprised in flagrante delicto with the deaconess of the Ladies of Charity of his parish—which would be greatly to their honor, since they are both in their eighties.”

Of course, much of this muckraking concerned little more than the sexual peccadillos of the great, but some of it had political implications, just as today in the case of the fake news about supposed orgies involving Hillary Clinton. The fate of Marie-Antoinette is the most spectacular example of how such slander could have disastrous consequences, but there were other instances. As I argued in Poetry and the Police: Communication Networks in Eighteenth-Century Paris, the circulation of mendacious rumors, many of them in songs and poems no longer than today’s tweets, led to the fall of the ministry of the Comte de Maurepas and a transformation of the political landscape in April 1749.

Although news of this sort could whip up public opinion, sophisticates knew better than to take it literally. Most of it was fake, sometimes openly so. A footnote to a scandalous item in Le Gazetier cuirassé read: “Half of this article is true.” It was up to the reader to decide which half.