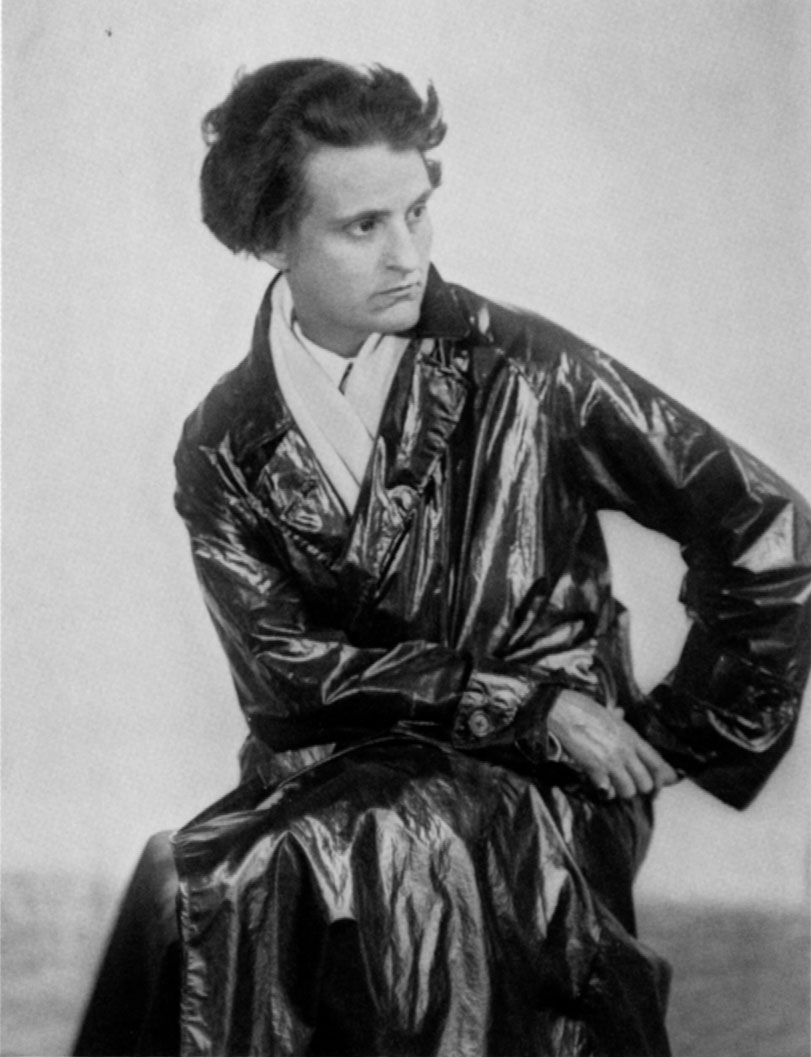

In one of the twentieth century’s most arresting portraits of a woman in the arts, Sylvia Beach, purveyor of Shakespeare and Company bookshop, sits wearing what appears to be a long, dark, patent-leather trench coat, its faceted surface accentuated by her hand-on-hip pose. Beach possesses the calm reverie of a Romantic poet, though her “very photogenic coat,” as the image’s photographer, Berenice Abbott, put it, projects a hallucinatory individuality that seems to come from the future. The subjects of Abbott’s earliest photography project, now published in full for the first time as Paris Portraits 1925-1930, are never dull—particularly the women, who, in a dismissal of her male colleague’s efforts, she aspired to capture as more than “pretty objects.”

Continuing Steidl’s steadfast commitment to great photographers’ complete oeuvres, Paris Portraits follows on the heels of the publisher’s five-volume The Unknown Berenice Abbott (2013), which covers the years 1929 to 1967. While she would make “Changing New York,” arguably her most famous series, after returning from Paris, Abbott’s European portraits document how international the community of modernists was between the wars, and are evidence of Abbott’s first experiments with lighting, angles, and equipment. In part due to lack of funds, her studio set was minimal. But the portraits’ sparseness only amplifies the ambition they contain—of both subjects and photographer. One of the pleasures of a great portrait is the unending present exposure it offers us, as if the sitter is just about to reveal something. This is one of the frustrations, too—so much in the frame remains invisible. “Photography,” Abbott declared in 1989, just a few years before her death, “helps people to see.” Looking at Paris Portraits, I think Abbott meant not simply to see more clearly, but to see how much eludes us in any view.

Abbott traveled to France as a sculptor on the encouragement of Man Ray, whom she had met in New York after dropping out of Columbia (she attended for one week). A self-proclaimed “crazy American kid” from Ohio with no money, she worked in Paris as Man Ray’s darkroom assistant, shooting pictures on her lunch break: “I would ask friends to come by and I’d take pictures of them. The first I took came out well, which surprised me. I had no idea of becoming a photographer, but the pictures kept coming out and most of them were good. Some were very good and I decided I could charge something for my work.” When Abbott started receiving more favorable reviews than her mentor, it was time for her to set up her own studio (at 44 rue de Bac and then 18 rue Servandoni) with loans from Peggy Guggenheim and Robert McAlmon, whose portraits appear in the book.

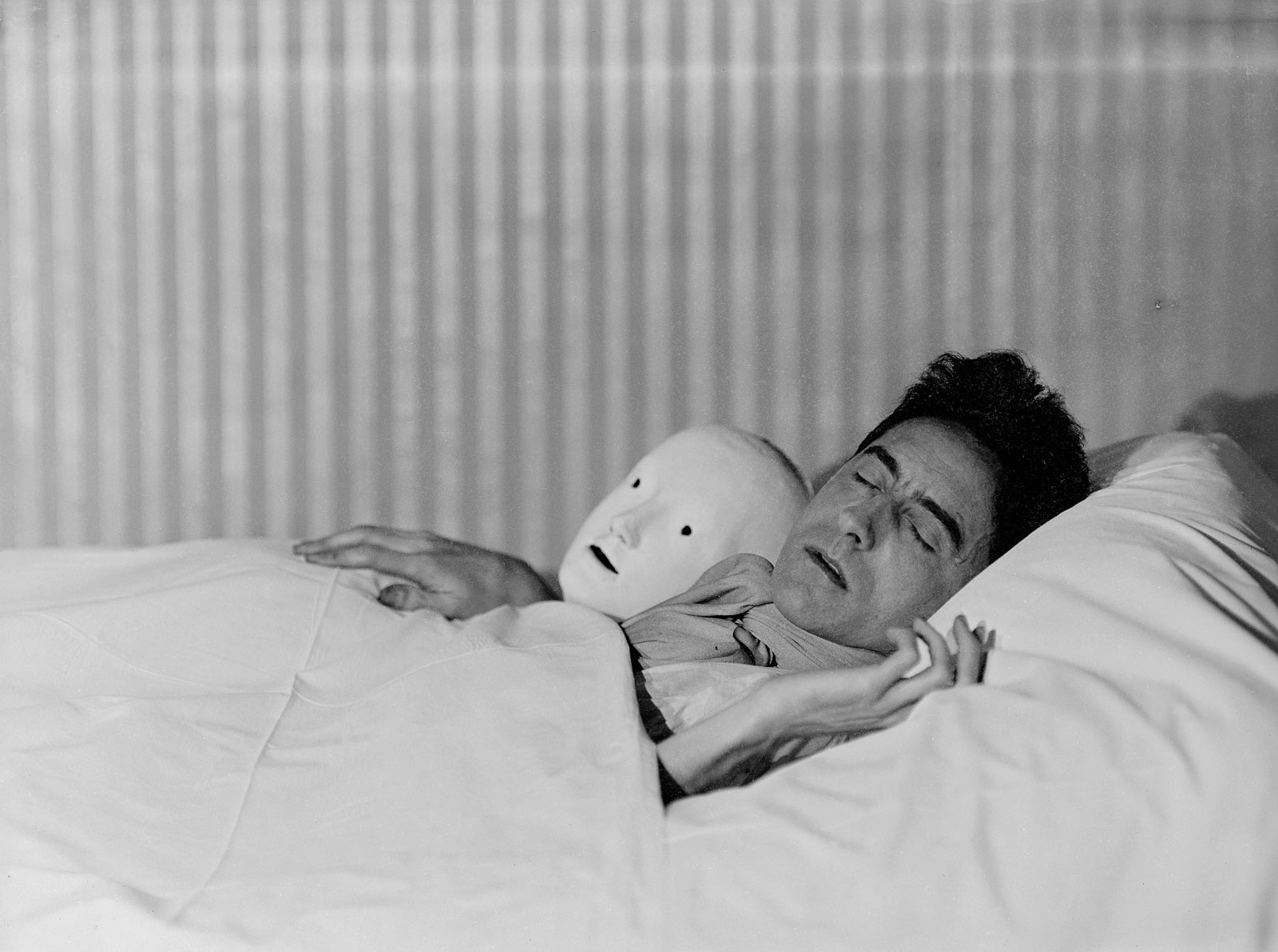

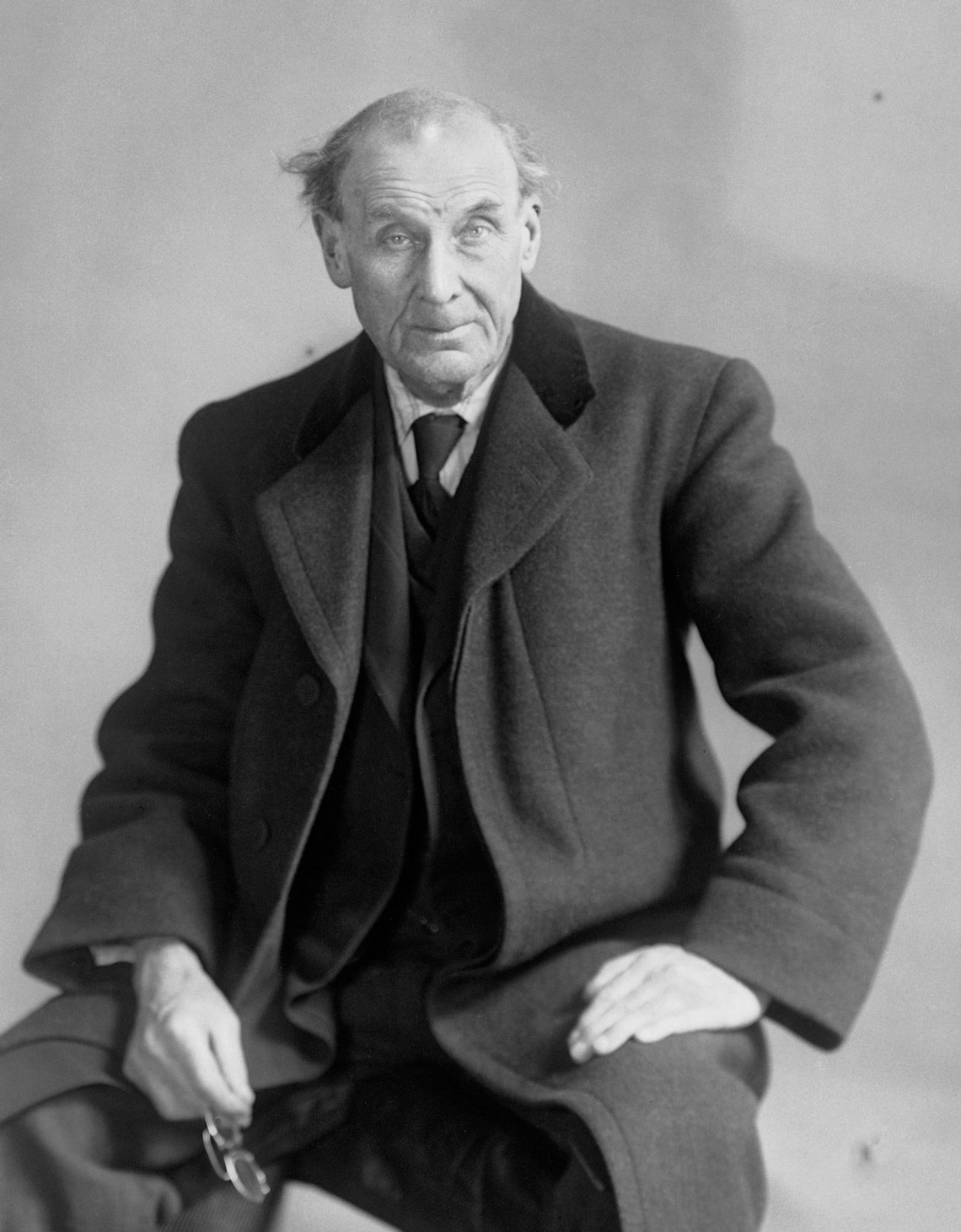

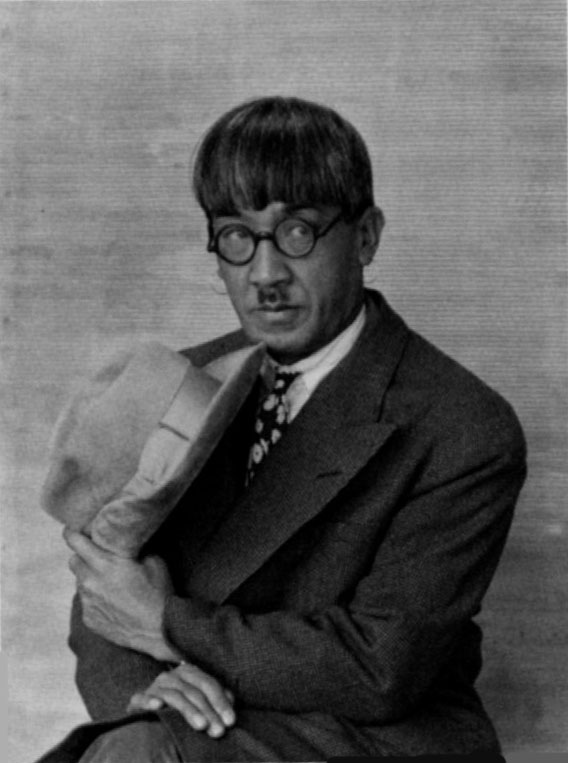

Abbott’s client list is dizzying: celebrated and disgraced politicians; Nobel laureates; Princess Eugène Marat, smoking and staring down the camera; a young Betty Parsons, then an art student; Djuna Barnes, who had been her roommate in New York; Jean Cocteau in bed with a white plaster sculpture head; Edna St. Vincent Millay. Abbott’s most moving portrait shows Eugène Atget, whom she admired for his unsentimental approach to documenting daily scenes of the city, just two years before his death in 1927. He seems shy to be on this side of the camera, hunched over in an overcoat and clutching his glasses, with a slight smile playing on his lips and a wisp of hair out of place.

Hoping to publish her portraits, Abbott had gone so far as to mock up a few pages of the book she envisioned and offer three titles: Faces of the 20s; Portrait of the Twenties, and Rebels of Paris. (While several exhibitions and small portfolios were put together of this work in her lifetime, she couldn’t get a publisher interested in the larger project.) Though her proposal showed images in a variety of layouts and sizes, Steidl has scanned the 115 portraits at exact ratio from the original glass plates, and so they are modestly scaled in the center of the page. Smooth and weighted, the book’s pages are a pleasure to handle, and the pictures’ size and tonal quality makes one look that much more carefully. Arranged alphabetically by subject, each photograph appears twice: once showing Abbott’s cropping, and once showing the negative’s full image. She preferred the close-up bust, usually cutting the picture off just below the hands, which are often her portrait’s most expressive feature. Sometimes, we learn, Abbott excluded disarming details, whether the fuzzy socks of the novelist Pierre Mac-Orlan, or the huge shadow cast by the slim writer François Mauriac.

Advertisement

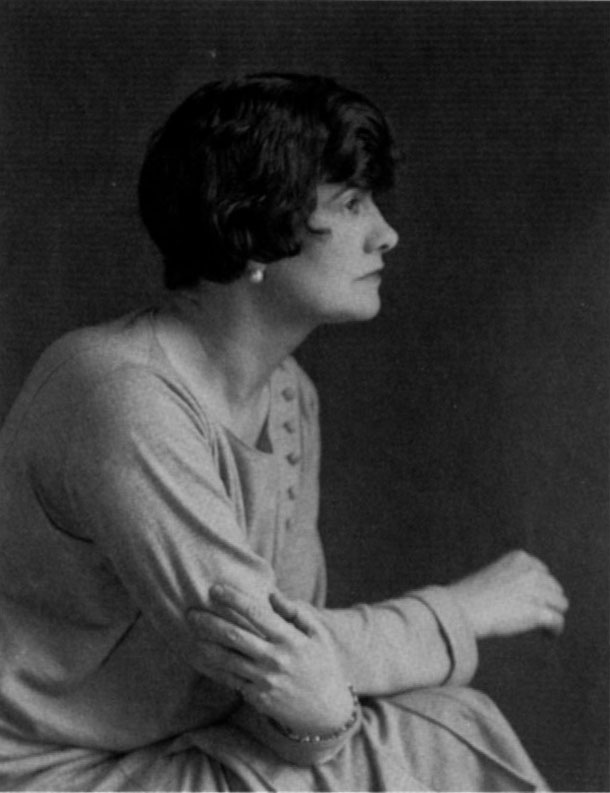

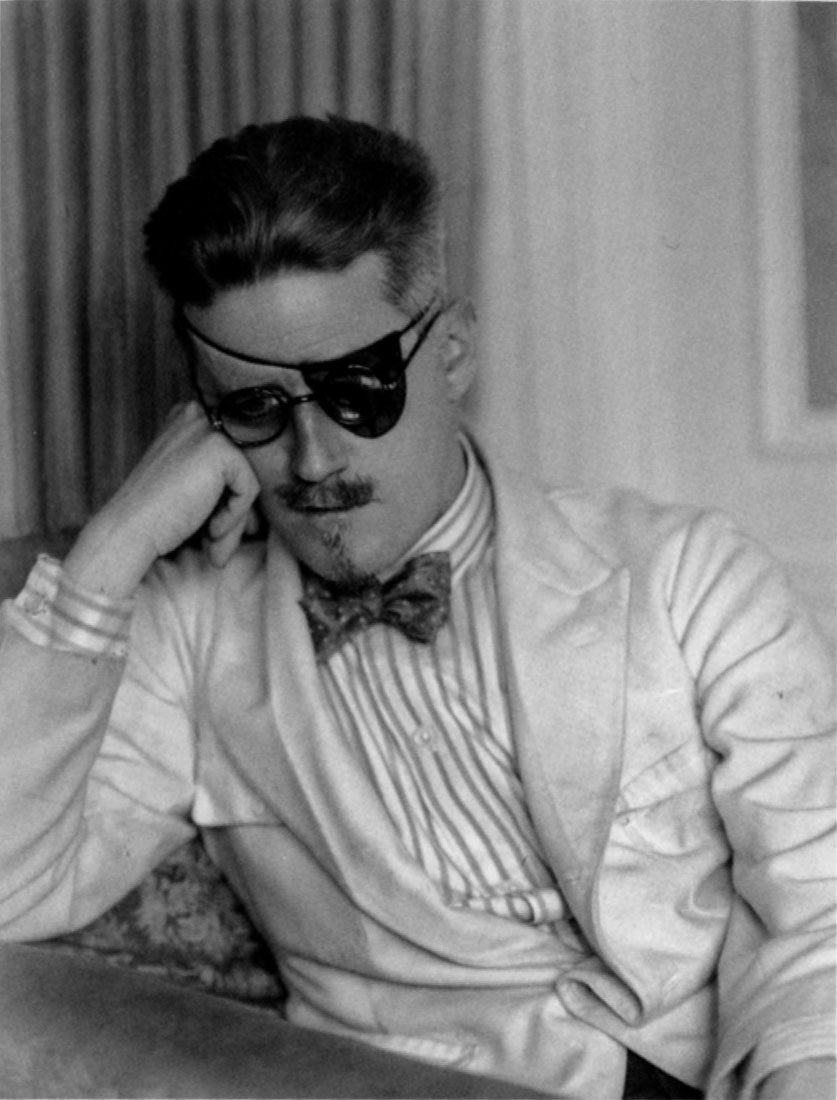

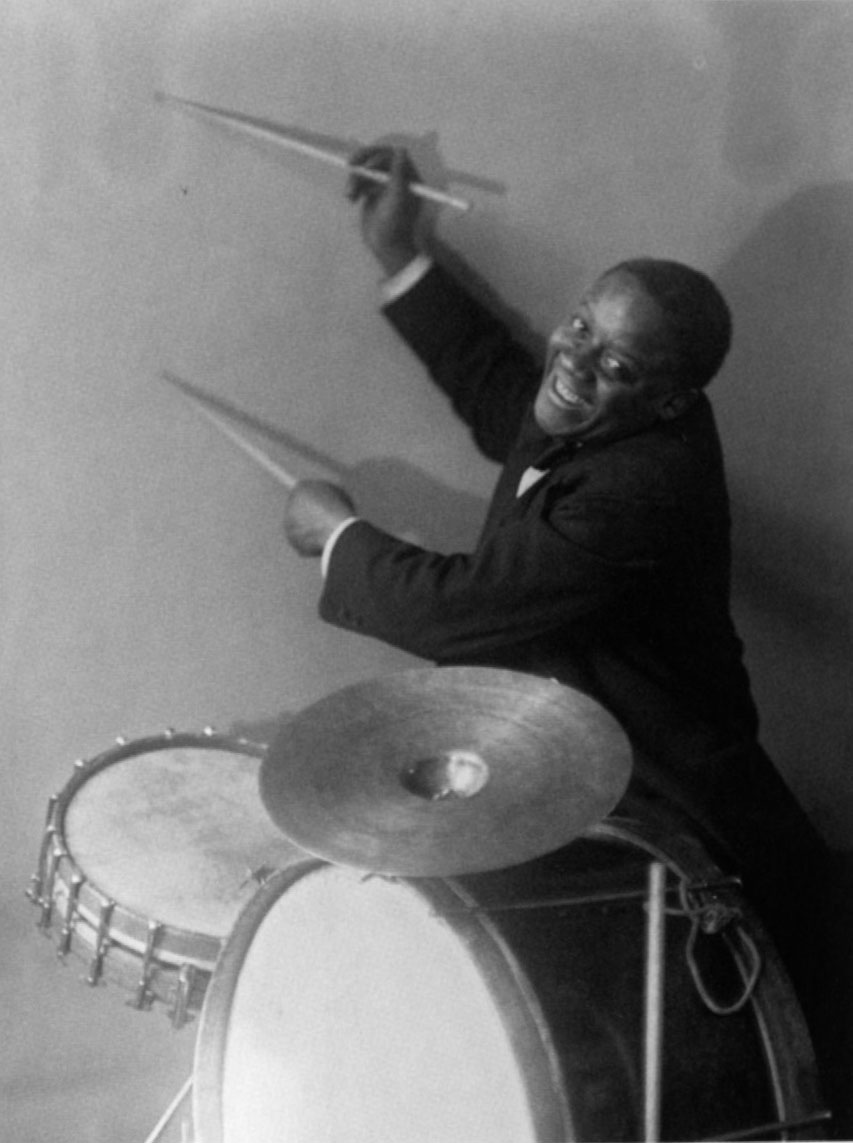

Accompanying some photographs are notes from Abbott’s later interviews with photographer Hank O’Neal. Of the animated, African-American nightclub drummer Charles “Buddy” Gilmore, who, sitting behind his set in her studio, breaks out drumming on her walls, she says: “I was simply crazy about his playing.” The famous designer Coco Chanel appears in a simple, pleated drop-waist dress against a background Abbott rigged up from corrugated cardboard; Chanel “was not particularly well dressed,” Abbott states. About Nora Barnacle Joyce, wife of the writer, clutching her hands in her lap, Abbott offers a detail beyond the portrait’s purview: “The music in her beautiful voice must have constantly pleased him; his style was so dependent on the sound of words and sentences.” Or, on her famous photographs of Joyce himself: “He told me about the severe trouble he had with his eyes. I used only natural light from the skylight, but he still had to wear his hat.” Like her passing observations, Abbott’s portraits are unpretentious and revealing. They are also as fathomless as the mirror in a photograph of Adrienne Monnier, Beach’s friend and fellow bookshop owner—a murky object that frames rather than reflects her.

Paris Portraits 1925-1930 by Berenice Abbott is published by Steidl.