In 1932, when the term “Socialist Realism” was officially used for the first time, all artistic organizations in Soviet Russia were dissolved, to be replaced by the Artists’ Union of the USSR, controlled by the state. That November the State Russian Museum in Leningrad held an exhibition, “Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republic.” Those years had been full of bold attempts to mix experimental art with propagandist modes, and the current show at the Royal Academy is a tribute to the 1932 exhibition, which the curators describe as “the last call for freedom of the arts,” before avant-garde art was suppressed and the ruthless utopianism of Socialist realism was the only approved style. This is a big, dynamic, disturbing exhibition, a blaze of artistic hope undermined by suffering, death, and despair. It is all about power and its perils.

On March 2, 1917, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, handing power to a socialist provisional government; in October, led by Lenin, the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Place in St. Petersburg and formed a new government. A year later Lenin launched his “Plan for Monumental Propaganda”: painting, sculpture, photography, posters, textiles, and ceramics were all to proclaim the glory of the Bolshevik state. Above all, as the first room of this show makes clear, the vast Soviet nation was expected to salute the Leader. Here is Lenin, in Isaak Brodsky’s painting of 1919, seated in suit and tie by a window amid swathes of crimson curtain, like a state portrait from the time of Louis XIV, pointing to his great plan, while demonstrators mill outside. Five years later he is dead: in Beside Lenin’s Coffin (1924), by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (who trained as an icon painter) he lies like a saint, or a huge fallen statue, while solemn mourners file past. Hail to a new Leader, a new style. Brodsky’s Joseph Stalin (1927) stands tall, a military figure with his thick hair and moustache, his hand resting gently on Pravda, the national press now literally under his thumb.

How should the artists respond? At first painters, composers, and poets thrilled to the Revolution, which seemed to offer untold freedoms, a chance to use bold new forms—Cubism, abstraction, street art, film, jazz, satire, fantasy—and to share in the making of a new nation. The mystical Wassily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall, and the Constructivists Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, and Lyubov Popova, responded with equal euphoric intensity. Kandinsky’s sizzling Blue Crest (1917) and Chagall’s The Promenade (1917–1918), showing himself whirling his bride Bella through the air, capture this heady exuberance, while the Cyrillic alphabet itself takes colorful flight in Ivan Puni’s Spectrum: Flight of Forms (1919). Experiment was already abroad in Russian art before the Revolution, with Tatlin’s Cubist-inspired constructions, his “Counter Reliefs,” and Kazimir Malevich’s invention of “Suprematism,” whose geometric abstraction inspired fierce, formal works, like Popova’s Space-Force Construction (1921). Yet there is a sense of terror, as well as hope, in these blazing, color-filled canvases. As cosmic spheres hurtle forward in spear-like shards of light in Konstantin Yuon’s apocalyptic New Planet (1921), the dwarfed crowds seem to cower as much as to rejoice.

As early as 1921, hope of free expression was fast vanishing and artists, writers, and musicians were increasingly disillusioned. They had seen the establishment of the Politburo in 1919 and the new “corrective” prison camps. They had watched famine sweep the country. They had witnessed the horrors of the civil war between the Bolshevik “Reds” and counter-revolutionary “Whites,” in which between seven and twelve million people died, and had learned of the brutal executions that followed the sailors’ mutiny at Kronstadt. At the same time, the state was becoming suspicious of artistic “freedom.”

In 1920 the Communist executive spoke out against “avant-garde artists”: a year later year the poet Alexander Blok—once a champion of the revolution—died ill and despairing, unable to write: “All sounds have stopped,” he told the writer Korney Chukovsky. “Can’t you hear that there are no longer any sounds?” That year, Kandinsky left to teach at the Bauhaus in Germany and Chagall returned to France. In 1922 Lenin drew up a list of 220 “undesirables”—philosophers, scientists, academics, and journalists—whom he wanted to deport before the creation of the Soviet Union that December. Soon Malevich’s Institute of Artistic Culture was forced to close after accusations of “counterrevolutionary sermonizing and artistic debauchery,” and although he continued to paint after 1928, when Stalin condemned abstraction as “bourgeois,” many of his canvases were confiscated. (From now on, it was decreed, art must be heroic, hopeful, “realistic,” glorifying the proletariat and Stalin’s utopian dream.)

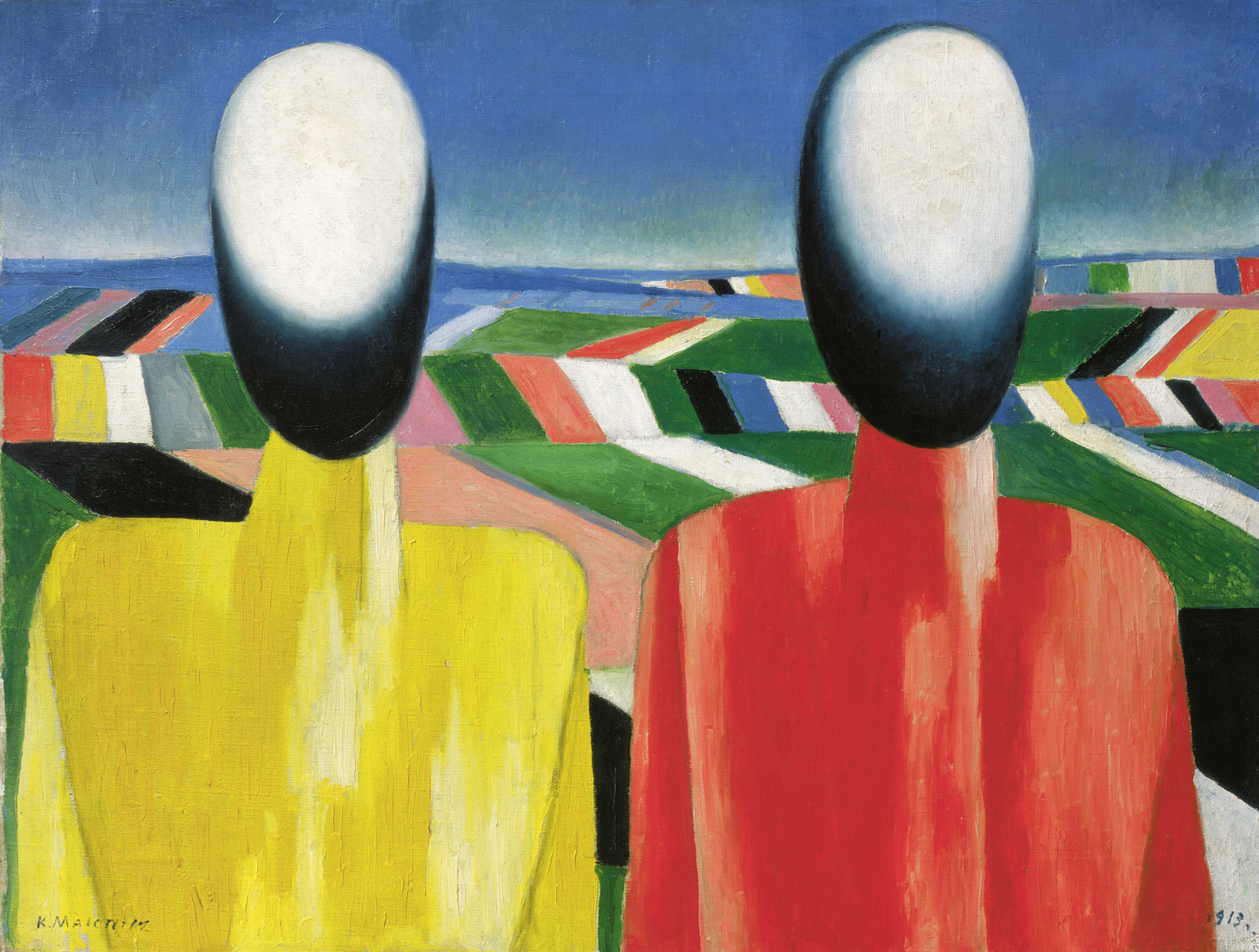

In the current show Malevich is given a room of his own, mirroring his solo room in the 1932 exhibition, where his stark paintings hang behind his white “architectons,” models of windowless and doorless buildings. His struggle and his independence of vision make him a star of the show. He caught the tragedy of the peasants’ lot and their loss of identity, giving their still forms empty, blank faces, while other painters dutifully celebrated the triumph of Soviet agriculture with images of shimmering cornfields and powerful tractors. The reality of the agricultural communes established by Stalin’s Five-Year was desperate: shock troops were sent to crush the kulaks—the independent peasants, who were burning their cattle rather than giving in. Villages were liquidated and terrible famine returned.

In Stalin’s vision, the hammer was even more important than the sickle. Once again, the artists were there to document the drive toward industrial power. Once again, their work is two-edged. The Constructivists embraced industry as a source for their art, inspiring photomontage, film, graphic art, and design. I was taken by surprise, for example, by the charm of the ceramics, and, I confess, amused by Mikhail Mokh’s Tea Set (1930), consisting of porcelain left over from the Tsarist State Porcelain Factory that had been decorated with Cubist steel-workers in red and black, with the imperial crest carefully painted out. (Somehow “having tea” with these delicate cups and jugs and sugar bowls seemed a very un-revolutionary activity.)

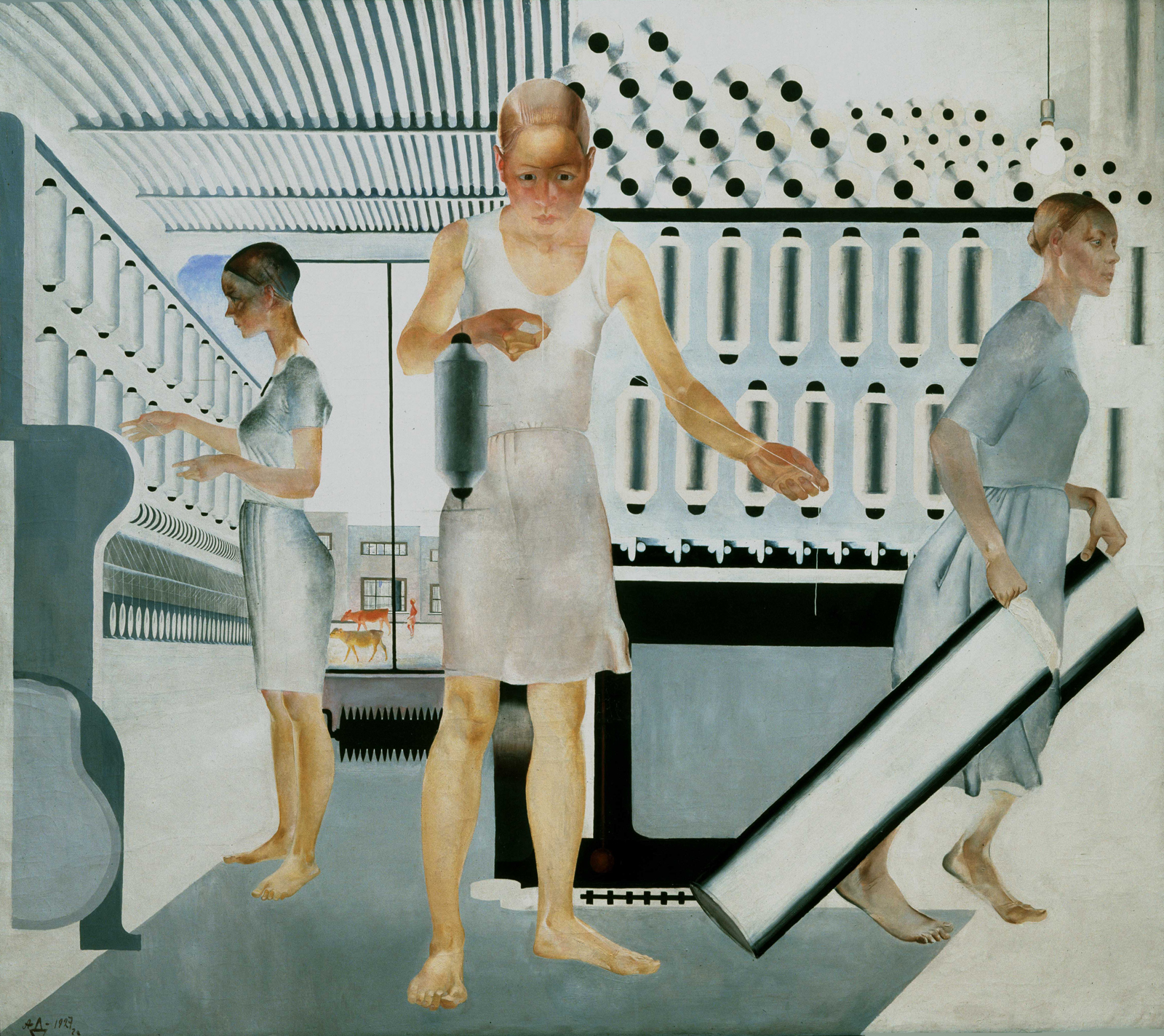

The black-and-white films and photographs, media uncannily suited to their subject, make one gasp at the beauty of the machine, the music and rhythm of levers and pistons. The well-muscled worker from the Komsomol, the Young Communist Organization, is transformed into a Greek god, or a Roman gladiator driving his chariot in Arkady Shaikhet’s Komsomol at the Wheel (1929). Yet the women in Alexander Deineka’s Textile Workers (1927), look like mechanized ghosts. And in Deineka’s collective portrait The Defence of Petrograd (1928), workers and soldiers are equally grim and dark.

Stalin’s relentless pursuit of industry brought as much suffering as his agricultural plans. Far from owning the means of production, workers became slaves, to be shot if they were slow or tried to go on strike. Thousands died of starvation, in accidents or from freezing cold. This exhibition does not skirt this. Alongside the striking images of energy are the oils of Eduard Alma Tenison, showing an exhausted worker and a solemn girl: on the table in each painting is a single plate, one with a fish, another with half a loaf of bread. No more. The shimmering birch trees and quiet lakes of painters who sought to portray “Eternal Russia” look like a longing escape. Even the distinctive figurative paintings of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (a name I didn’t know before, to my shame) who took over as President of the Leningrad Regional Union of Soviet Artists in 1932, feel full of a yearning nostalgia. In his huge canvas, Fantasy (1925) the peasant riding the leaping red horse of revolution does not look forward, but back, to a vanished world.

The Royal Academy brings us close to the history and to the artists, filmmakers, poets, and musicians who recorded and endured it. We come face to face with the Futurist poet Mayakovsky photographed by Alexander Rodchenko; Sergei Eisenstein by Man Ray; Blok, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Sergei Prokofiev by Moisei Nappelbaum; Anna Akhmatova by Nikolai Punin, her common-law husband and one of the organizers of the 1932 exhibition. Mayakovsky committed suicide in 1930, and in the enclosed “Room of Memory” in the exhibition’s final room, artists and poets—including Osip Mandelstam, Akhmatova, and Punin—join the thousands of men and women shot on Stalin’s orders or sent to a living death in the hard labor of the gulags over the next twenty years.

It is impossible and wrong, in this fascinating exhibition, to separate art from politics, utopian propaganda from dystopian tragedy. Aesthetic judgement is inevitably compromised. Some may think it obscene to celebrate this period in Russian art: yet it is surely right to make us confront it, to see the boldness of the art and to try and fathom the mixed motives, the hopes and fears and struggles of the artists involved. Right too, when the headlines are full of Trump and Putin, to remind us of the history.

“Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932” is at the Royal Academy in London through April 17.