The British royal family in the twentieth century had no great love for advanced art. Kenneth Clark wrote that George V was “much disturbed” by J.M.W. Turner’s pictures when he visited London’s National Gallery in 1934. “Turner was mad,” the king declared. “My grandmother [Queen Victoria] always said so.” George VI’s wife, Elizabeth (best known as the Queen Mother), in old age reminisced to A.N. Wilson about a Windsor Castle poetry evening during World War II. “I think it was called ‘The Desert,’” she said of one comical reading. “First the girls [the present queen and her sister, Princess Margaret] got the giggles, and then I did and then even the King.” When Wilson asked, “Are you sure it wasn’t called ‘The Waste Land’?” she replied, “That’s it…. Such a gloomy man, looked as though he worked in a bank, and we didn’t understand a word.”

But as a magnificent exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art indicates, Britain’s reigning dynasty wasn’t always this way. During the eighteenth century it was vastly more cultivated, especially the three remarkable women who are the focus of “Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte and the Shaping of the Modern World.” They were, respectively, Caroline of Ansbach (1683-1737), the wife of George II; Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (1719-1772), the widow of Frederick, Prince of Wales, who died before he could ascend the throne; and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818), the consort of George III. All were born in small eastern German principalities and were chosen for their arranged matches primarily because they were Protestant. (That had become a requirement after Parliament’s Act of Settlement in 1701, which forbade members of Britain’s royal house from marrying Catholics.)

These three German Georgian graces—whose contributions to British life spanned more than a century—brought far more to their adopted country than just political stability. They were all exceptionally well educated, intellectually curious, and aesthetically attuned, even by the standards of the day usually reserved for men. This was true especially when it came to the Enlightenment ideas and principles being advanced at the time. The princesses’ careful schooling in a multiplicity of subjects central to the Aufklärung (Enlightenment) included a strong emphasis on science, particularly botany and astronomy, along with the classical curriculum of Greek and Latin. Their attainments far outstripped almost all of the British nobility and much of the aristocracy.

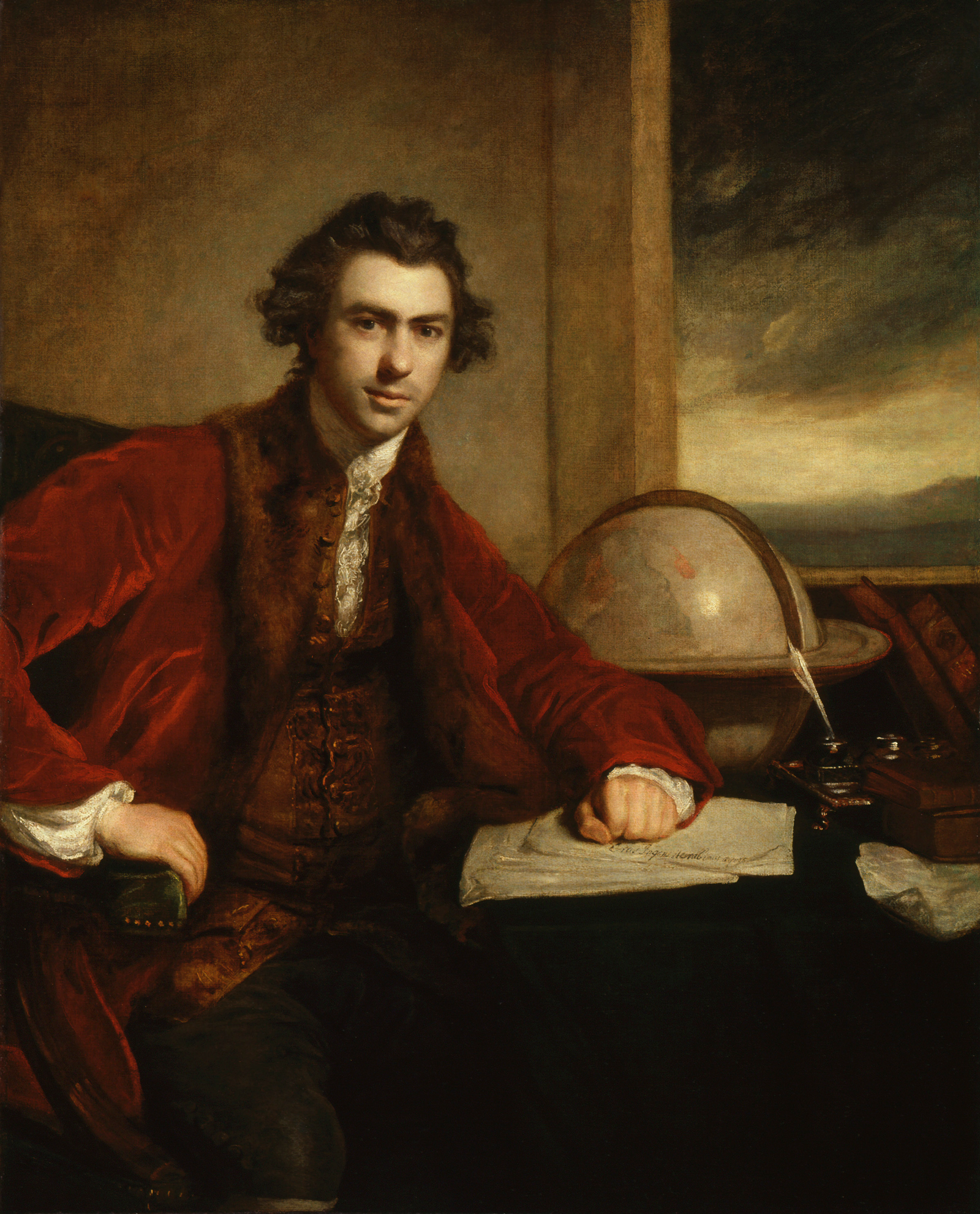

Although nearly three hundred fascinating objects in many mediums are assembled for the New Haven show, the splendid portraiture on display—much of it from Britain’s Royal Collection, which has loaned more pieces to this exhibition than to any one of its kind—alone makes “Enlightened Princesses” worth the trip. There are two startlingly immediate chalk likenesses of Tudor courtiers by Hans Holbein the Younger; Joshua Reynolds’s veritably exhaling canvas of Joseph Banks, the pioneering botanist who accompanied James Cook on his first South Pacific voyage and discovered some 1,400 plant species unknown to Europeans; and a stunning full-length oil painting of the widowed Augusta by the Scottish master Allan Ramsay, in which she turns her gaze to the viewer as she sweeps past in a dusty rose taffeta dress topped with a gauzy black bolero and hood.

Rather than merely unrolling a series of discrete themes linked by the exhibition’s timeline, from the accession of George II in 1727 to the death of George III in 1820, or falling into the kind of indiscriminate assemblage—ethnography sans frontières—that have plagued so many recent museum presentations of contemporary art, “Enlightened Princesses” explores the objects on view in fresh relation to the social and intellectual settings of its patrons.

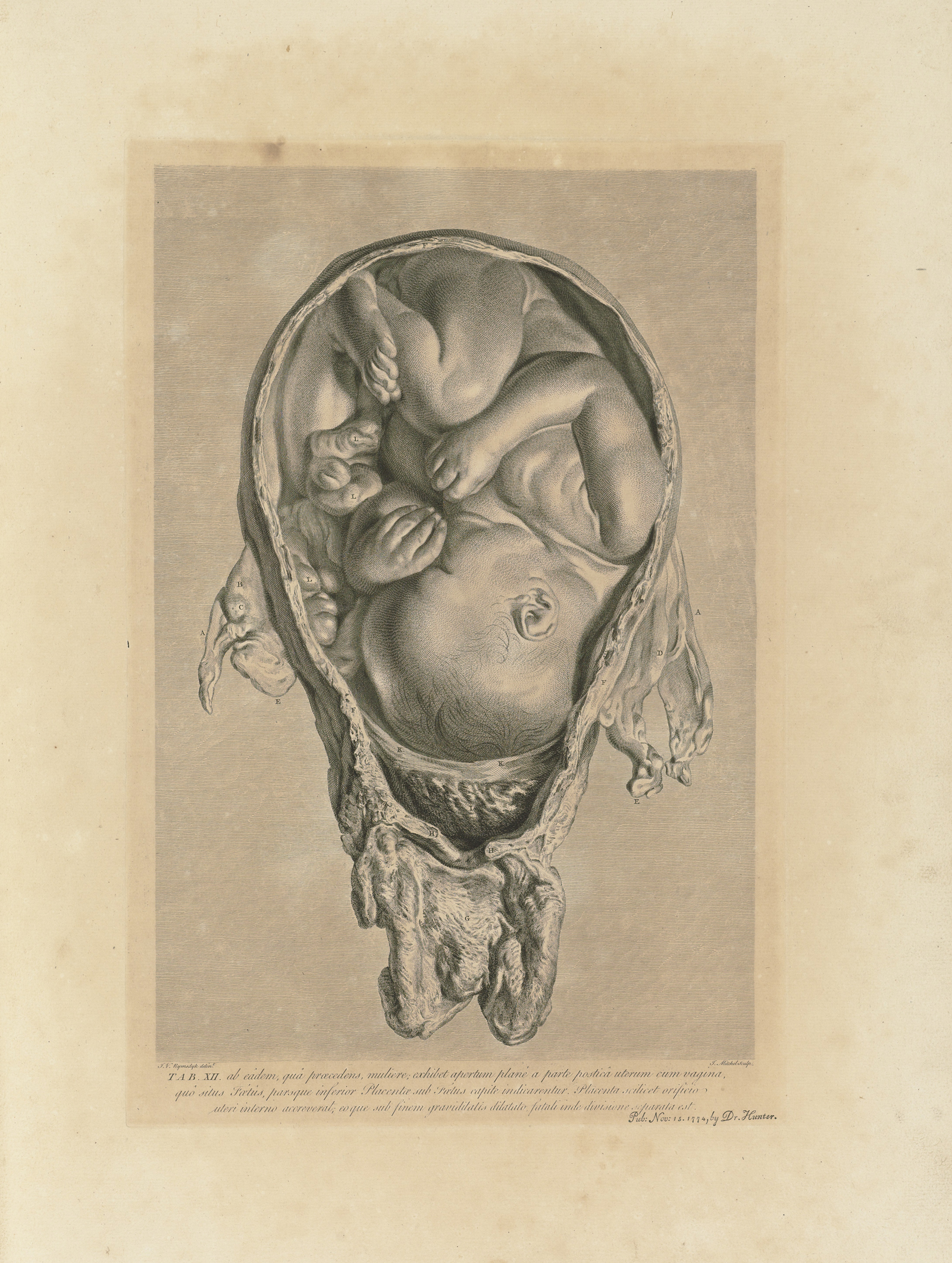

Here we can see the ways in which such diverse but interrelated fields as the study of horticulture and the industrial manufacture of fabrics and ceramics influenced each other—consider the porcelain, commissioned by Queen Charlotte and patterned with melon leaves. Or how advances in obstetrics laid the foundations of modern child care: in the 1770s Charlotte promoted research on maternal health; her physician, William Hunter, was the first to dissect a pregnant woman’s uterus and study its anatomical composition. The fact that successful reproduction lay at the very heart of the royal system—exemplified by Charlotte and the uniquely uxorious George III, who had fifteen children together—gives extra meaning to this part of the exhibition.

There were notable differences among the three princesses. Caroline of Ansbach (as she was born) was the mental powerhouse. As a young woman in Berlin she corresponded with Gottfried Leibniz, the renowned philosopher and mathematician whose Panglossian view of a benevolent universe was diametrically opposed to the grand but indifferent clockwork posited by his British contemporary Isaac Newton. Yet Caroline was able to reconcile these two disparate conceptions when she moved to London in 1714, and in due course welcomed Newton into her intellectual circle (which in the 1730s also encompassed such masters of arts and letters as Handel and Pope). The odds that one royal lady would engage with the two men who independently discovered calculus are in themselves astronomically small.

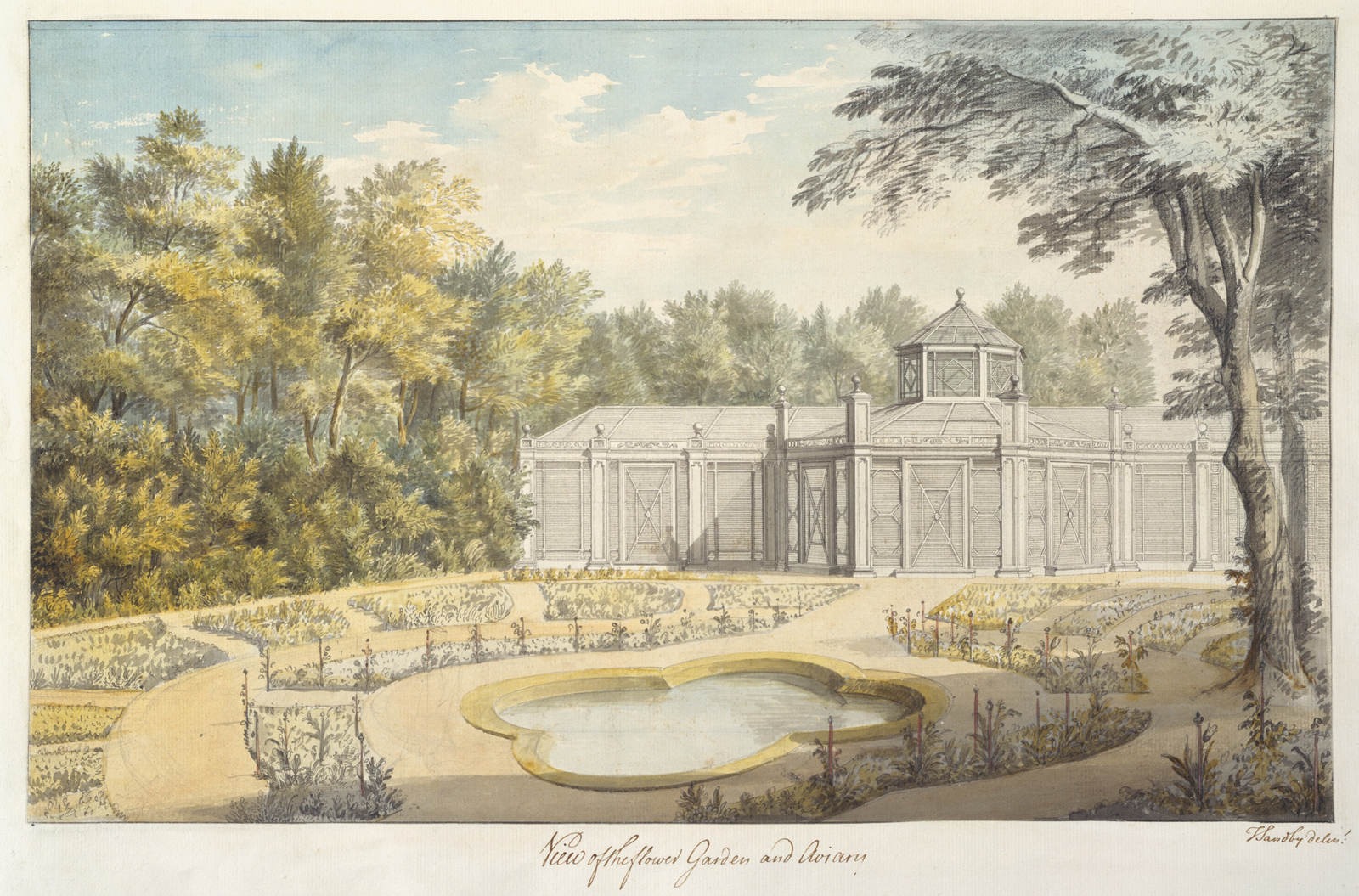

A generation later, Caroline’s daughter-in-law, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, was no slouch, either, though her pursuits ran more specifically to the natural sciences. She is best remembered for her ambitious expansion of the royal garden at Kew, southwest of London, which has grown into one of the world’s foremost horticultural institutions. But Augusta had considerably less time for extracurricular activities than either Caroline or Charlotte. After the death of her husband at forty-four she largely devoted herself to securing the prospects of her eldest son, who went on to become George III and reign for six decades.

The third heroine in this royal progress was Charlotte, whose dynastic arrangement with George III (Caroline and George II’s grandson) turned into a love match after all. The antic art of caricature was already well grounded in Britain before George III and Charlotte, but the couple’s unconventional interests—his scientific farming (which involved crop rotation, fertilizers, and other innovative concepts), their abstemious diet, and her hands-on nurturing of their children—made them ripe targets for the leading satirists of the day. In their scathing drawings, several of which are included in the show, Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray seized on the royal couple’s bug-eyed, slack-lipped physiognomies and churned out cartoons of rollicking viciousness that can still incite laughter. In one of Gillray’s caricatures, Charlotte gives her six daughters unsweetened tea. They pout in displeasure as she coaxes them to drink it. “You can’t think how nice it is without sugar.”

During the nineteenth century there would be another decisive infusion of German blood into Britain’s royal house when Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha married Queen Victoria—George III and Charlotte’s granddaughter. But although he was a polymath with great sensitivity for the arts and sciences, Albert’s subordinate view of women and his wife’s ultimate acquiescence to him (as stressed in Julia Baird’s perceptive new biography, Victoria: The Queen) marked a regression from the dominance of highly educated royal ladies during the preceding century.

“Enlightened Princesses” does not shy away from politically contentious topics, such as colonialism and slavery, which were central to the British Empire’s exponential economic growth during this era, but it does so in a nonideological and un-hectoring way. In a drawing by William Kent, we see Queen Caroline as Britannia, sitting not in the palace but on a quay, where boats bring goods from far-off shores.

Nothing hits closer to home now than the section devoted to smallpox vaccination, which was introduced to England in 1721 by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, who had her son inoculated there in accordance with local practice. Her aristocratic imprimatur and especially the endorsement of Queen Caroline gave the procedure inestimable help in being widely accepted in Britain, in striking contrast to the irresponsible agitation of American anti-vaxxers today who have found new support in the Trump White House.

At a time when fictive Disney princesses reign over pop consumer culture for girls—last summer the entertainment giant announced its first Latina princess, Elena of Avalor, for an eponymous animated television series, doubtless prompted by demographic trends—it’s difficult to remember that real princesses once wielded broad intellectual influence. Both of the incumbent Prince of Wales’s wives—the charismatic, doomed Diana and the tough, tenacious Camilla—struggled to complete secondary school and never considered going on to university, typical of most aristocratic British women of their generation.

The subtle feminist undercurrent of “Enlightened Princesses”—for example, the way in which a progressive attitude toward motherhood was viewed as essential for improving society—is not the least among its thought-provoking themes. The show’s gorgeously illustrated, deeply researched catalog is another major achievement, with more than thirty essays remarkable for their many fresh insights on this rediscovered trio and the fascinating epoch in which they lived.

Advertisement

“Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the Shaping of the Modern World” is at the Yale Center for British Art through April 30. It will then be on view at Kensington Palace from June 22 through November 12.