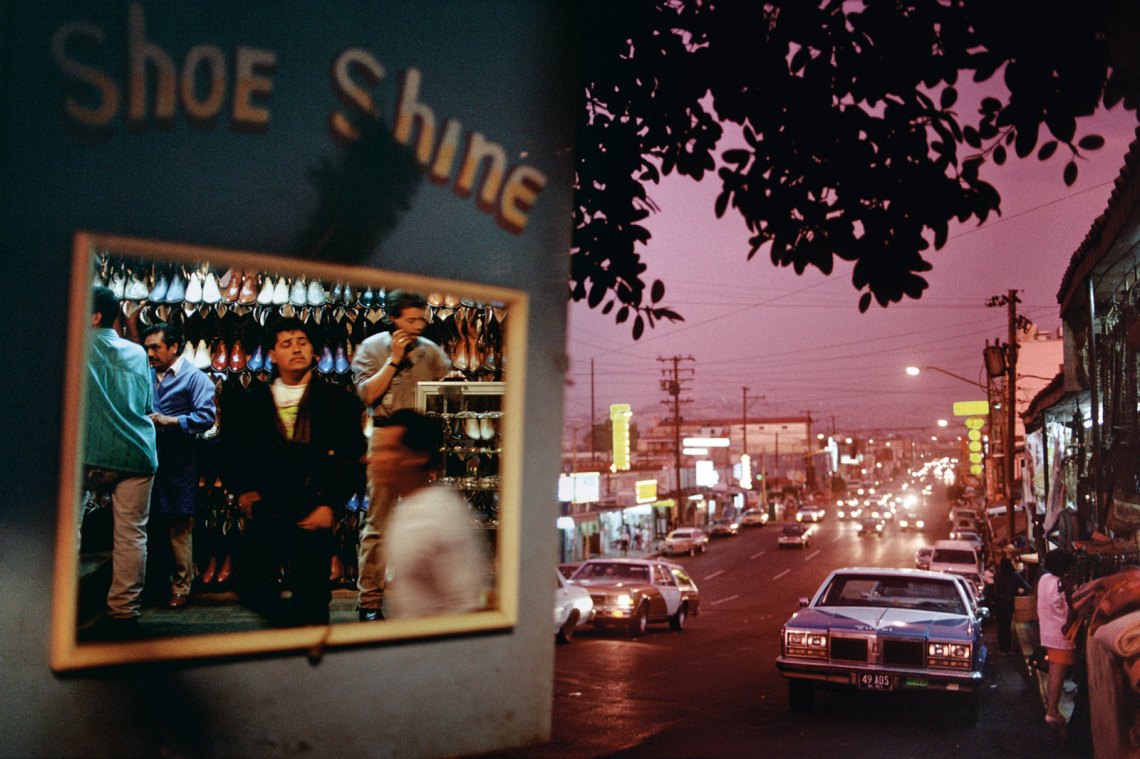

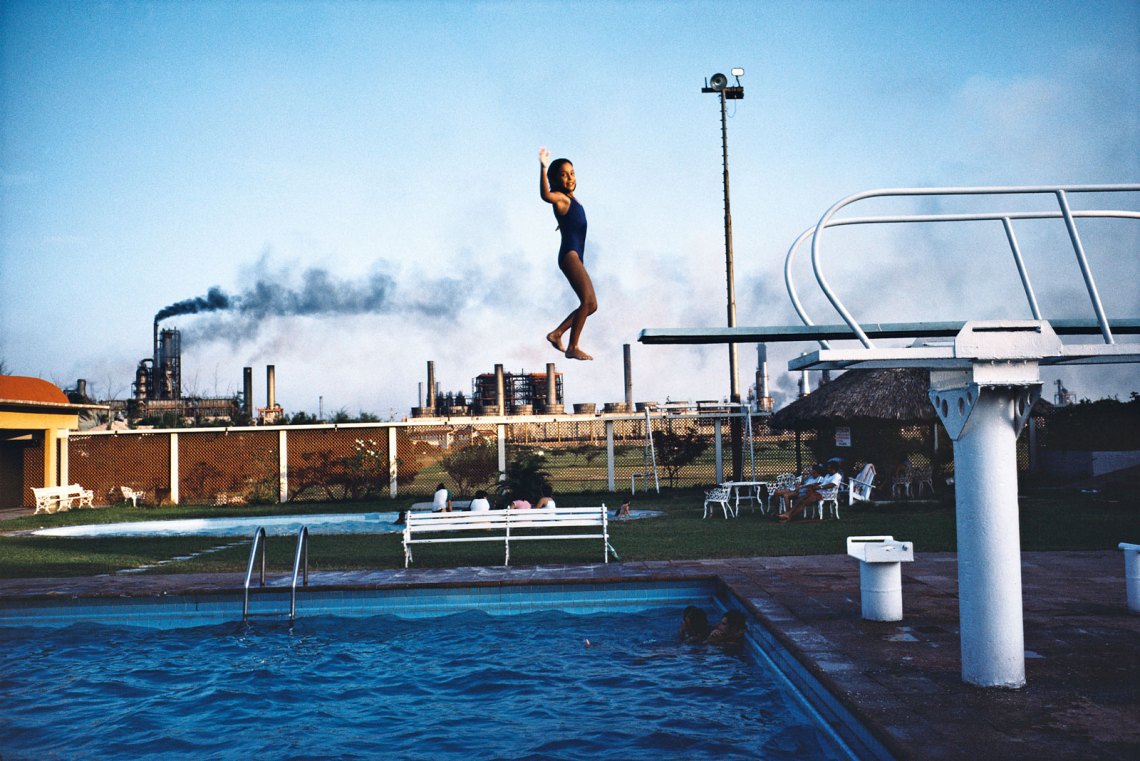

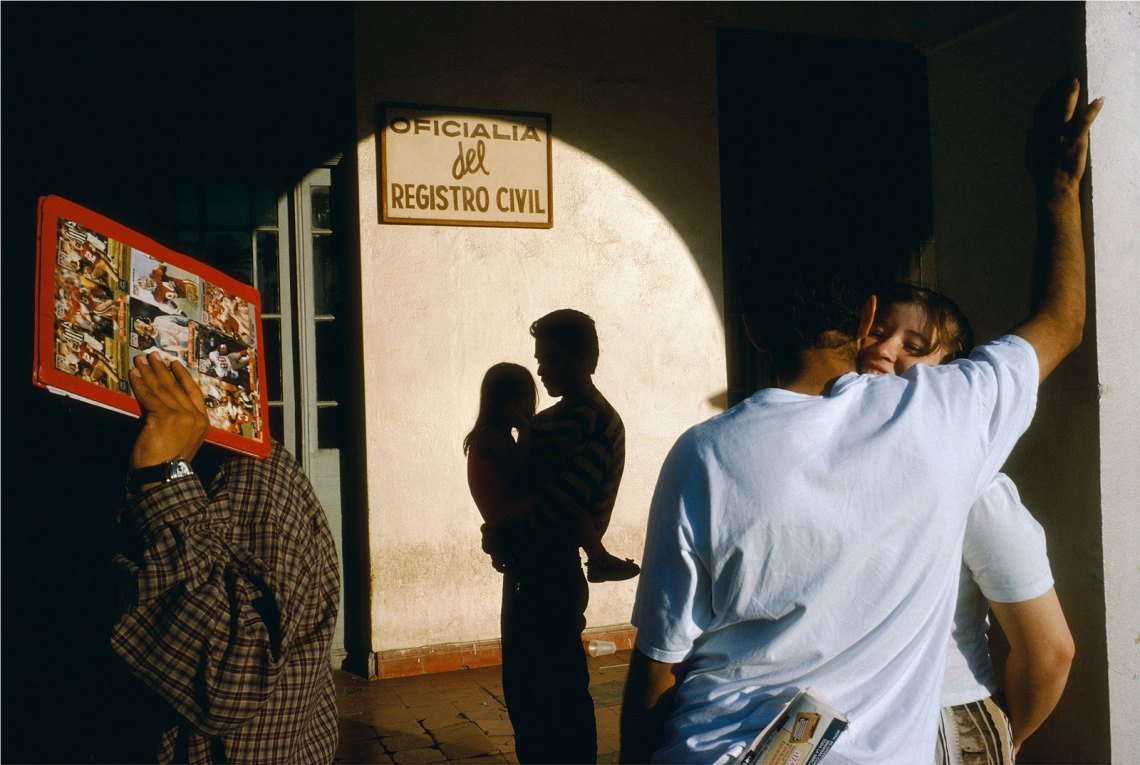

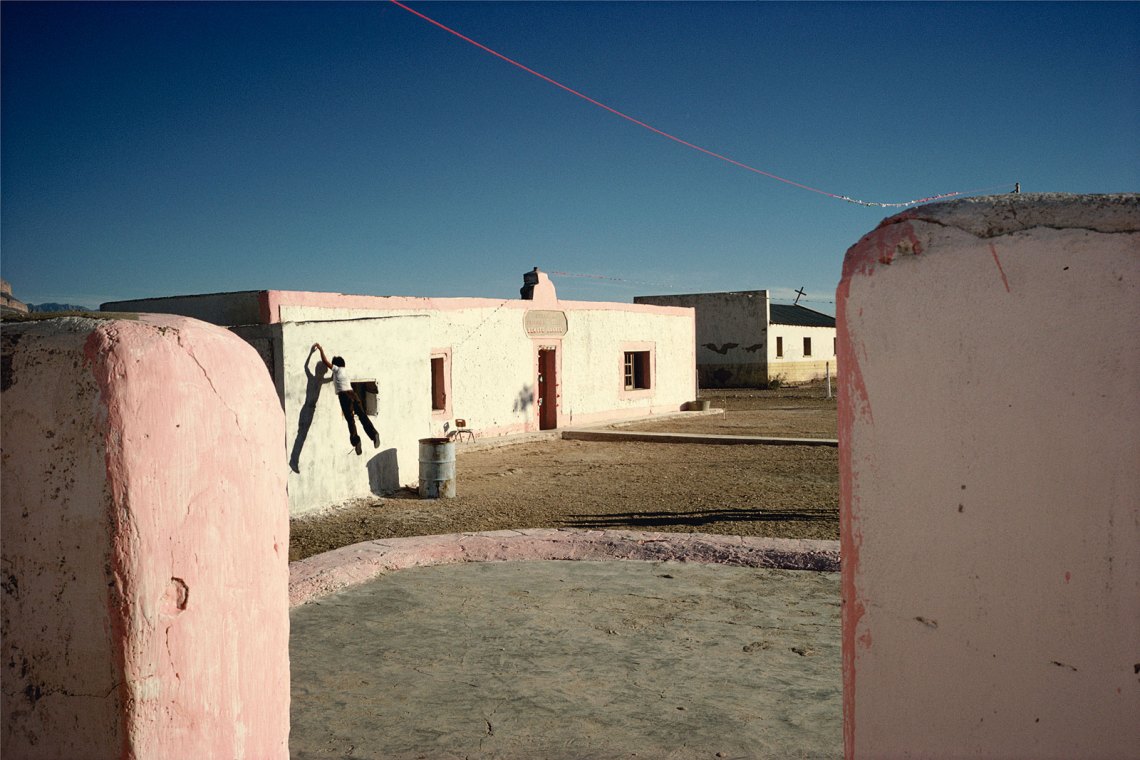

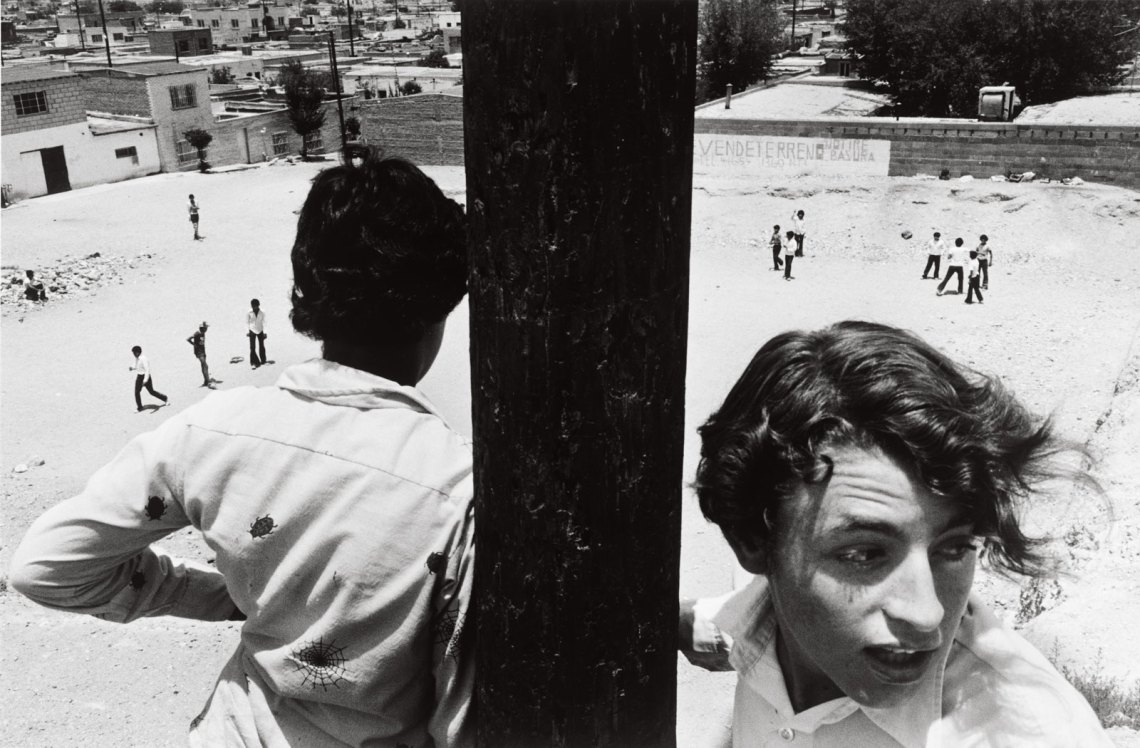

It was late December when Alex Webb asked me to write a piece for a book that collected thirty years of his photographs of Mexican streets. I remember it because my family and I were trying to cut as short as possible the New York winter by spending a month in Tepoztlán—a town forty-five minutes from Mexico City. I was familiar with Webb’s work on the Mexico-US border and found the project exciting because of his unusual way of looking at the country we both love: his superb pictures are all about the way in which the brutal light of Mexico casts a shadow on what one would rather not see. Webb is a master of color, but satisfied, too, to leave things in the darkness.

During one of our frequent trips to Mexico City, I was with my children in a cab going down Avenida de los Insurgentes when I pointed to the strange, almost painfully modernist Polyforum Siqueiros—an art gallery and cultural venue that the muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros designed late in his career, in the 1960s, when he was the last surviving maestro of his kind and Mexican revolutionary nationalism was long past its heyday. The Polyforum is a building with such a weird shape that the always-poisonous popular wisdom in Mexico City has rebaptized it the “Coliflorum” (coliflor meaning cauliflower)—and it certainly looks like a vegetable grown in hell.

I told my children while pointing to it, the three of us sitting down in the backseat of a cab, feeling a bit foreign in the city in which we had all been born but had not lived for a long time: “The guy who did that thing is the same one who fired the machine gun whose bullet holes we saw in Trotsky’s bedroom, near your grandparents’ house.” They were, of course, immediately interested in the building.

In which other city could one say something like that while running between stoplights? I grew up in the neighborhood of El Carmen, on Calle Viena: a quiet, middle-class, residential road that happens to have, at one end, an insane monument engraved with the hammer and sickle: Leon Trotsky’s grave. The tomb is in the center of the garden of the house that a Mexican anti-Stalinist gave to Trotsky, after he was exiled from the USSR and expelled from Europe. The grave somehow embodies one of those unexpected, historical knots of international intrigue so common in Mexico City—the world’s navel; its often overlooked crossroads.

Although it holds Trotsky’s bones, the street of Viena is short and unremarkable, except maybe for its jacaranda trees, which bloom in late February and produce a hallucinatory purple carpet of dead flowers. It was not until I returned to visit my parents, after I moved out of Mexico long ago, that I learned the street contained meanings beyond my experience of it—that it hosted ghosts more important than that of Navarro, my high school classmate who committed suicide by overdose, just before AIDS became an illness with which you could live; or the carcass of the abandoned Cinema Coyoacán, where I received my sentimental education watching low-budget Mexican comedies and second-run Hollywood blockbusters. Maybe the best way to describe the spirit of El Carmen is through our relationship to film: our neighborhood got to watch Raiders of the Lost Ark so late, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was already running in the movie theaters of the more prestigious parts of the city.

Calle Viena begins at the Vivero Coyoacán, the immense plant nursery founded in 1901, where every tree in Mexico City that’s younger than a century old was born. It may be this forest wall that kept our neighborhood insulated even from Hollywood, what made Trotsky’s allies think Stalin’s hitmen could not reach him there. Standing with your back to the tree nursery, Calle Viena runs to the east for only eight blocks, ending where, not long ago, the Churubusco River ran aboveground; now it runs underground, through a tube.

The natural fortress didn’t protect Trotsky very well, anyway: Ramón Mercader, a Catalonian envoy of Stalin, was still able to pound an ice axe into Trotsky’s head—after the pro-Stalin Communist Siqueiros, accompanied by some local talent trying to gain points in Moscow, had failed to kill Trotsky in a first attempt at murder, with the spectacular burst of gunfire that my children admired so much.

Advertisement

There is something movingly provincial about that brutal story, something tender and very proper for a tiny street, my street, that for a few weeks was the unsuspecting scene of a global conflagration. On one hand, there is the cold, professional, solitary assassin who quietly slipped into the circle of the Soviet leader in exile, and succeeded a highly planned blow. On the other, there is a bunch of friends, filled to their ears with tequila, firing a storm of bullets in the middle of the night, and failing. For Stalin and his envoy, Trotsky’s death was an objective; for the Mexican Communists, it was a performance.

Adapted from Álvaro Enrigue’s essay, “Vienna, Mexico,” in Alex Webb’s La Calle: Photographs from Mexico, published by Aperture and Televisa Foundation.