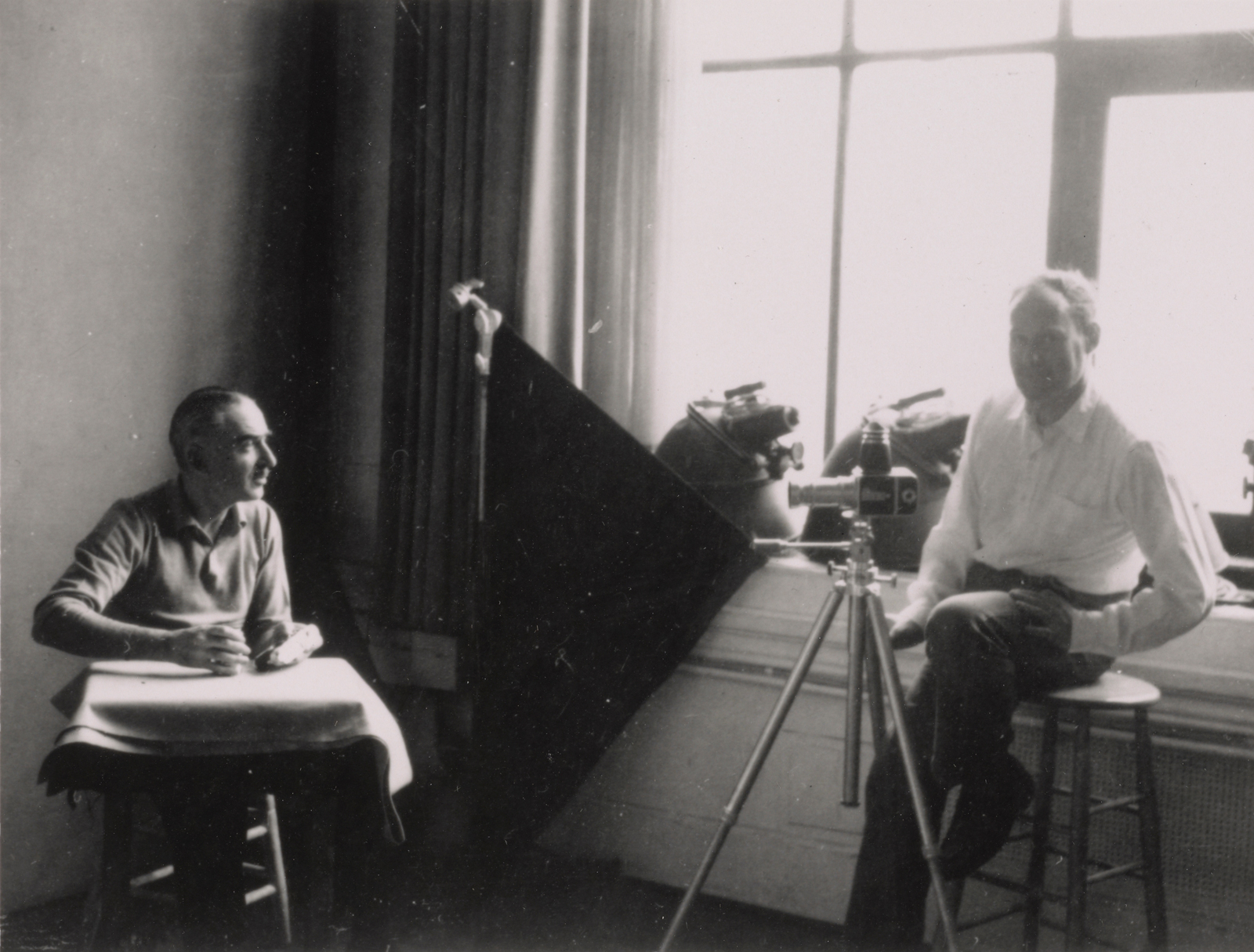

Among the most startling interviews I’ve ever done was one with Alexander Liberman, the longstanding editorial director of Condé Nast, for my 1990 Vanity Fair profile of Irving Penn. For more than four decades, Liberman had been the great photographer’s primary patron, but when I pressed him on the exact nature of Penn’s genius, his mouth hardened into the crocodilian rictus that those who worked closely with him dreaded. “Penn has never had an original idea in his life, it all comes from me,” Liberman averred. “I always need to give him a sketch of exactly what I want because he has no imagination.” (The photographer hated his first name, and intimates always addressed him as “Penn.”)

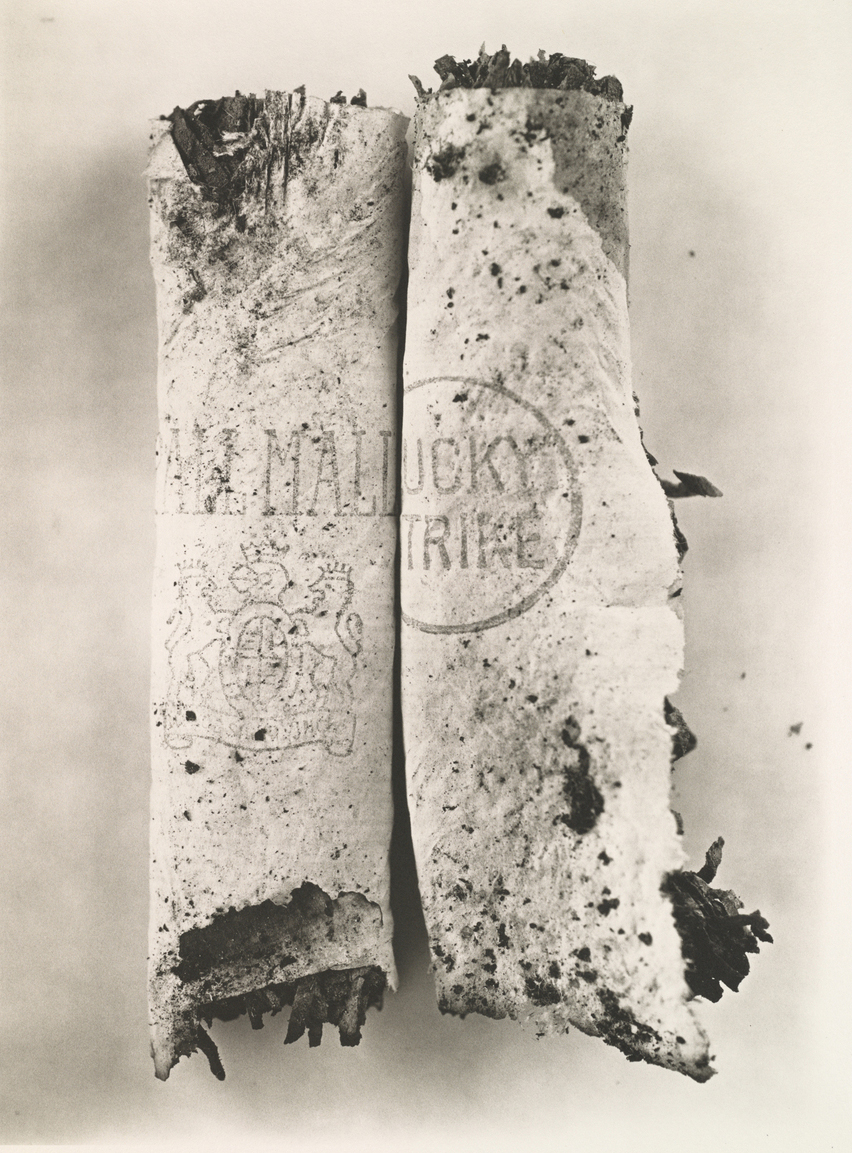

Early the next morning Liberman called, allowed that he had been perhaps a bit intemperate, and asked me to return for another conversation. He thereupon took a more measured tone, but still could not resist some backhanded barbs. Of Penn’s self-consciously arty black-and-white shots of detritus found on the street he declared, “He gave nobility to garbage. The cigarettes remind me of Egyptian mummies.” It seemed obvious that Liberman, an ambitious painter and sculptor who complained that he was scorned in serious art circles because of his pre-eminence in the fashion world, resented Penn’s far greater critical acclaim.

“Penn is a graphic photographer,” Liberman told me. “He draws, and out of his drawings—my drawings, sometimes—comes a vision that is, in a way, two-dimensional. It’s practically a typographical vision. An enlarged letter has a great resemblance to a Penn portrait. But on the page it prints and in the magazine it stands out. He needs the printed page.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s magisterial exhibition, “Irving Penn: Centennial,” which includes more than two hundred works spanning his seventy-year career—much of it part of a huge promised gift from the Penn estate to the museum’s permanent collection—offers a fresh opportunity to consider Liberman’s assessment. Impeccably curated by Jeff L. Rosenheim and Maria Morris Hambourg, the retrospective includes everything from his career-defining fashion images (many of them depicting his mannequin wife, the incomparably beautiful Lisa Fonssagrives) to his intensely personal series of fading flowers from the late 1960s onward, which those close to him understood to be elegiac meditations on Lisa’s aging.

Penn’s finest efforts now look better than ever. Among them are his classic portraits of midcentury cultural luminaries—Igor Stravinsky with a hand cupped around one ear; a prematurely world-weary Truman Capote; and the rail-thin Marcel Duchamp like a Giacometti sculpture come to life. All were posed against gray industrial felt backdrops or wedged into an acute-angled corner that somehow prompted his subjects into remarkable revelations through posture and facial expression. “They couldn’t run away,” Penn explained to me of this canny compositional contrivance, “and they belonged to me as subjects for that moment of time. They felt good about it, too. Their rears were protected and they could project their attitudes outward in one direction.”

Nonetheless, in contrast to his rival Richard Avedon’s plein air fashion escapades—revisited in the recent Paris exhibition, “Avedon’s France”—there can be a stiflingly hermetic quality to some of Penn’s studio work. I’ve never been a fan of his finicky early still lives, which are so overly art-directed that any relation to the messy abundance of the seventeenth-century Dutch paintings that inspired him is lost. Or the existentialist pretensions of the gutter trash series—clearly influenced by the postwar Arte Povera notion that there is something inherently profound in decay. The Met survey does nothing to convince me otherwise.

Penn was well aware of his shortcomings. “I’m a surprisingly limited photographer,” he insisted to me, “and I’ve learned not to go beyond my capacity. I’ve tried a few times to depart from what I know I can do, and I’ve failed. I’ve tried to work outside the studio, but it introduces too many variables that I can’t control. I’m really quite narrow, you know.”

Yet it is equally difficult to deny that Penn was the supreme studio photographer of the twentieth century. His artistry both emerged from and depended on his very specific, highly aestheticized commercial work, and if he needed Liberman’s financial and artistic support, he certainly made the most of their collaboration, despite the sadistic cat-and-mouse tribulations he was subjected to.

Penn craved the cushy apparatus that Condé Nast in its glory decades provided him in return for his editorial exclusivity (although he was allowed to do uncredited advertising work, including campaigns for such unglamorous products as Jell-O pudding and Plymouth automobiles.) His corporate perks included a studio on lower Fifth Avenue—far from the publisher’s midtown headquarters to minimize interference—plus assistants and darkroom technicians to abet his demanding vision.

Advertisement

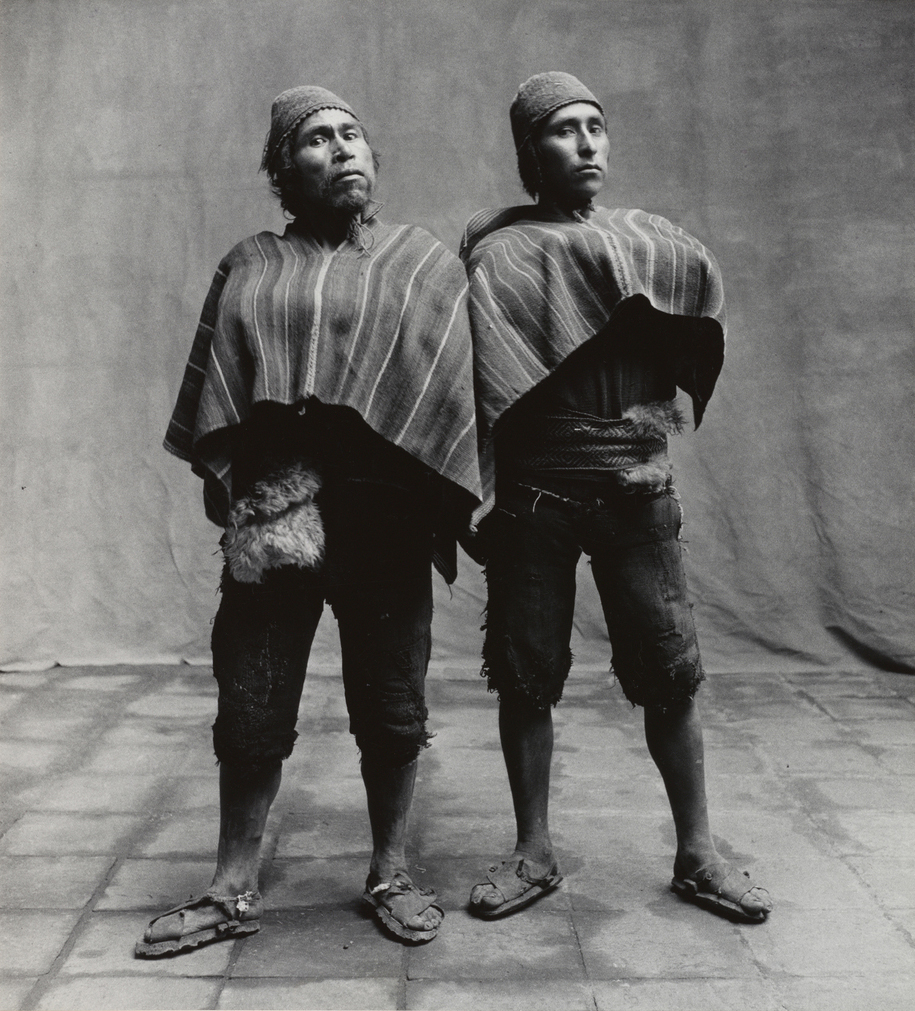

But he still came up with surprises. Though I found the majority of the Met selections familiar, some of the most thrilling ones were not, including lesser known examples from what I consider Penn’s career peak: his 1948 portraits of Peruvian Indians in Cuzco, where he’d gone to shoot American fashion models for Vogue. There he discovered local residents, including two Quechuan men possessed of such innate dignity that they might have stepped out of a Mantegna fresco, and immortalized them with what can only be called pure genius.

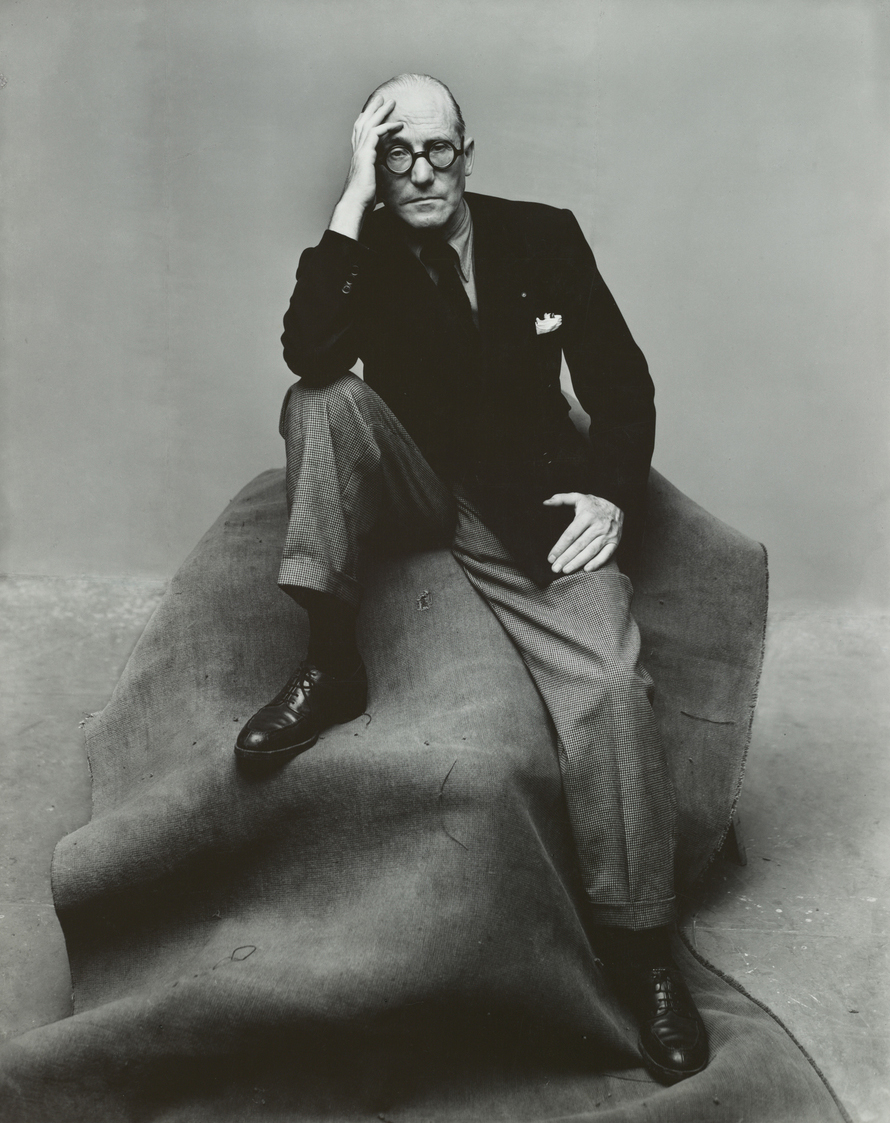

His 1947 portrait of Le Corbusier, dressed, as was his wont, like a prewar French bank manager, combines the immutable gravitas of Ingres’s canvas of Monsieur Bertin with the majestic candor of Matthew Brady’s photographs of Lincoln. What draws one’s eye most, though, is not the architect’s attire but the biomorphic seat Penn has created for him by draping felt over some low object. This improvisation presages the voluptuous contours of Le Corbusier’s most famous work, the Ronchamp Chapel of 1950-1955 in France, which he did not start to design until three years afterward.

Though decades of repetitive assignments understandably took their toll on Penn, he was able to sporadically re-energize himself through projects such as his remarkable portraits of indigenous tribal peoples in New Guinea, Dahomey, and Morocco (1967-1971), which made their self-designed garb look infinitely more creative than anything coming down the runways of the Paris couture.

During Penn’s final decades he grew increasingly concerned with securing his place in history and methodically covered multiple institutional bases. In 1990 he gave 120 prints of his photographs to the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C. Five years later his archive went to the Art Institute of Chicago, and seven years before his death in 2009 he laid the groundwork for the current exhibition by donating prints from his 1949-1950 series of monumental female nudes to the Met. This was followed by the Irving Penn Foundation’s posthumous gift to that museum of 150 more works. A perfectionist in all things, he was likewise a peerless estate planner.

Despite Penn’s habitual kvetching about being a tool of commerce, the Condé Nast connection gave him early access to fresh currents of creativity, and he was always alive to them. The cultural and artistic ferment of the first two postwar decades in America, and Liberman’s conviction that Vogue should contain features on emergent trends in the arts, allowed Penn to document the best of the newest. Whether Liberman’s harsh assessment of Penn was spurred by poisonous envy or contained a kernel of truth, the show suggests that the master photographer’s commercial work laid the foundation for his deeply original contribution to the medium. Indeed, the Met’s splendid overview of this grand obsessive proves that his supposedly Faustian bargain was not such a bad deal after all.

“Irving Penn: Centennial” is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 30. The catalog, edited by Maria Morris Hambourg and Jeff L. Rosenheim, is published by Yale University Press.