Like many children of the 1970s, I first encountered Saul Steinberg’s drawings on the cover of The New Yorker. Or, to be more precise, I first saw printed reproductions of his drawings on New Yorker covers plastered all over the walls of my family’s bathroom in Omaha, Nebraska. Like many bathrooms of the era, ours had become a do-it-yourself decorating project for my mother, for which New Yorkers—and, apparently, reproductions of nineteenth-century Sears-Roebuck catalog pages—were deemed de rigueur sometime during the years of the Ford administration. I would spend extended sessions puzzling over the pictures, which towered not only above my child-sized perspective, but also beyond the limits of my understanding. (I think my mother put the antique whalebone corset and uterine syringe advertisements near the ceiling for a reason.)

But it was the “View of the World from Omaha, Nebraska” poster framed in our den that most fascinated me. Its title, typeset in the legitimizing New Yorker font, and its curious, childlike cartoon map of familiar downtown buildings disappearing into a pastureland of distant pimples labeled with names like “Pittsburgh,” “Philadelphia,” and “New York” before rolling off into the ocean absolutely captivated me with the idea that I could be living in such an important city as Omaha—especially given that The New Yorker had seen fit to highlight the fact on a sheet of paper four times the usual size of the magazine. After all, Nebraska is more or less traditionally considered the geographic center of the United States—and is actually labeled as such in the real View of the World from 9th Avenue, drawn by Steinberg, which appeared on the March 29, 1976, cover of The New Yorker. The original did not, unfortunately, appear on our bathroom wall, so when I first saw the genuine image years later as a teenager, I still felt a lingering security within its strange loop of place-time—even if only then was I getting the actual joke.

Historically speaking, View of the World from 9th Avenue was a cartoon nuclear reaction, smashing together what New York thought of itself with what the world thought of New York, all on the cover of The New Yorker itself. It spawned countless city-centered rip-offs that spiraled their particle trails through 1970s dens across the nation, including mine. To this day it remains the magazine’s most famous cover not featuring its unofficial mascot, Eustace Tilley. Yet the thieving of Steinberg’s easily thieved premise rankled him for the rest of his life, the most visible sign of his success legitimizing yet also blurring the importance of his contributions to cartooning, to say nothing of twentieth-century art. A new exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, “Along the Lines: Selected Drawings by Saul Steinberg,” gives some sense of his electrifying work.

As a cartoonist myself, I am dismayed that there’s little in the show I can steal, the crossover in the Venn diagram of the image-as-itself versus as-what-it-represents being depressingly slim. I am painfully aware that in comics, stories generally kill the image. But Steinberg’s images grow and even live on the page; somewhere in the viewing of a Steinberg drawing the reader follows not only his line, but also his line of thought. Describing himself as “a writer who draws,” Steinberg could just as easily be considered an artist who wrote; as my fellow cartoonist Lynda Barry puts it, his “drawing went not from his mind to his hand but rather from his hand to his mind.” Or as Steinberg himself declared at the beginning of a 1968 television interview, “[my hand explains] to myself what goes on in my mind.”

One can’t overstate the importance of Steinberg’s working for reproduction, of his creating drawings to be disseminated to the mailboxes, laps, and, I guess, bathroom walls, of receptive readers and not, at least initially, to museum walls. The Museum turns on an eminently Steinbergian tool—the rubber stamp—and, as a lithograph, manipulates the idea of reproduction while pictorially lampooning and dissembling it. Identical figures are plunked out to represent visitors and viewers of (what else?) official stamps of approval; over the museum’s horizon, stamps rise like suns, the entire composition grounded and buttressed by illegible signatures and, of course, more stamps. As a visa-seeking emigré in his early life, Steinberg’s fascination with legal seals is easily understandable. Riverfront and Certified Landscape pivot on the objectively ridiculous but fundamentally necessary imprimatur of government made corporeal, territorially imprinted as a skein of walls and fences. Steinberg quietly added his own signature directly into the rather unaccommodating landscapes—are they farms, factories, or concentration camps?—rather than putting it in the traditional antiseptic nonspace outside the pictorial “border.” But in The Museum, Steinberg bundles the stamp’s sanctioning power and aesthetics into the frame of the art itself, stamping his own authorizing red imprimatur in that expected nonspace outside the image, along with his signature (legible, one notes) and, as a digestif, a blind stamp (a stamp without ink, visible by the impression it leaves on the page), just to snuff out any lingering doubt about the drawing’s authenticity and, by proxy, the artist’s own legitimacy.

Advertisement

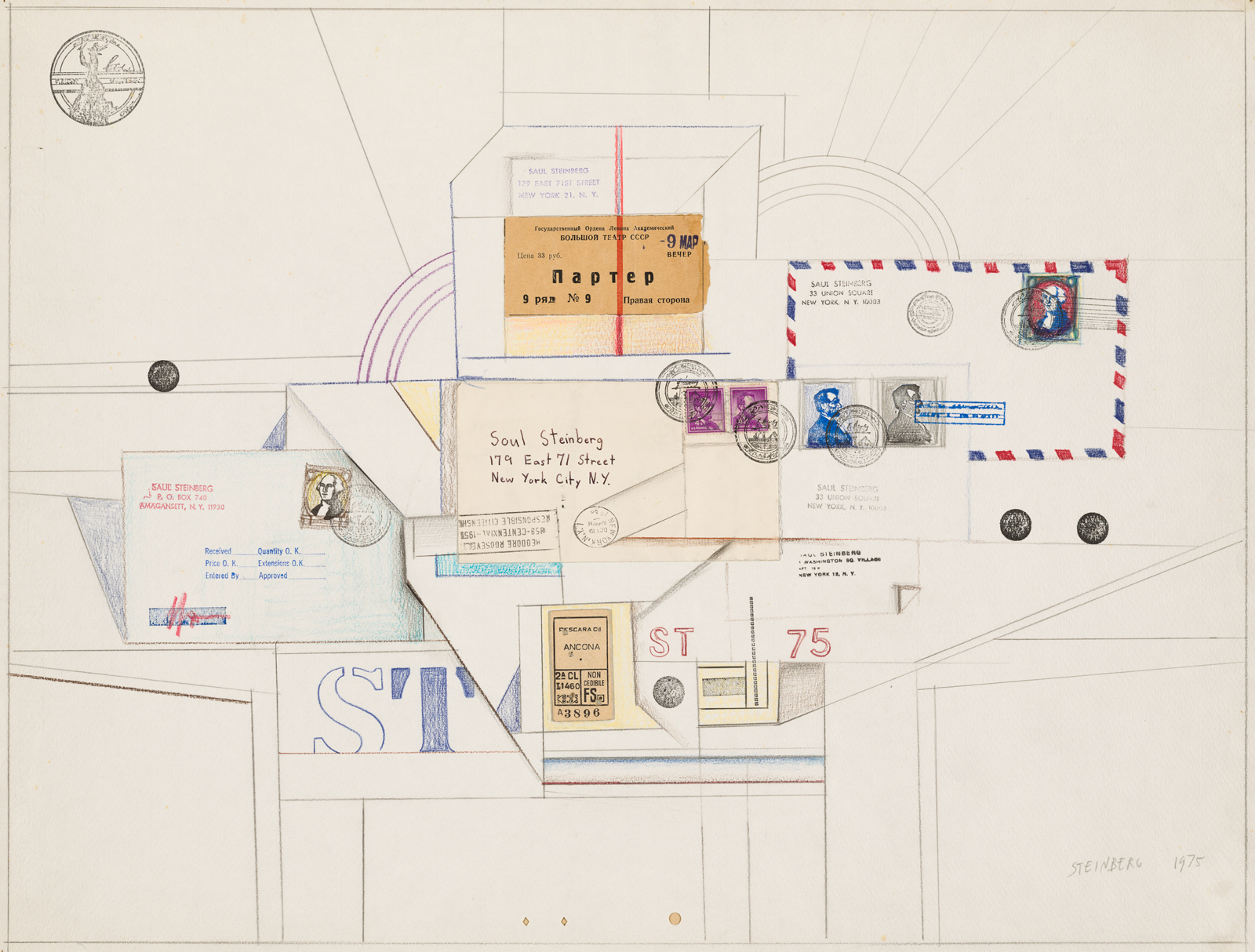

Even a seemingly dashed-off stamp-and-doodle drawing such as Untitled (Rush Hour) rewards the viewer with a fizz of epiphany: all of the figures and cars are made from impressions of the same four rubber stamps, so that the flow of the urban workforce is made clear only in relation to the perspective of the building into which they rush and from which they leave, and all this is captured graphically with the very clerical tools that grant the city its life. Even the seemingly random zig-zag gestures of the stamped taxicabs’ bumpers synaesthetically combine to create the sound of traffic in the reader’s eye. Konak and Untitled (Table Still Life with Envelopes) are similarly constructed around office ephemera—an official invoice, a postal envelope—but within the deliberate strictures of Analytical Cubism. For Steinberg, Cubism wasn’t only a metaphysical investigation but an immigrant’s observation: “As soon as I arrived in New York, one of the things that immediately struck me was the great influence of Cubism on American architecture…the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building, jukeboxes, cafeterias, shops, women’s dresses and hairdos, men’s neckties—everything was created out of Cubist elements.” New York Moonlight appears observed by alien eyes, the spiky Chrysler Building looking more like an Aztec totem or butterfly genitalia than a skyscraper. Steinberg does not resort to the cliché of lit windows stretching into the sky; instead, his buildings sink into the horizon, not so much looking like Manhattan in the moonlight as feeling like the metallic, acidic impression of wet moonlit pavement.

Sometime in the 1970s, Steinberg’s work took a turn for the observed, typified in the Art Institute’s collection by the lovely Breakfast Still Life. Steinberg’s wife, the artist Hedda Sterne, criticized this “realistic” direction, but Breakfast Still Life is hardly realistic, with its pencil purples and greens cast against the usual metaphysical Steinberg white, capturing in reverse-thermal snapshot the stuff of the artist’s morning—black coffee, bread, cornflakes, butter, jam, Chianti bottle, a newspaper—which Steinberg sets up in alienating opposition to the tableau most humans seek as a daily reassurance. Seemingly finding it freeing to leave the artificial atmosphere of his earlier work and return to the pleasure of observed drawing, Steinberg remarked, “in drawing from life I am no longer the protagonist, I become a kind of servant, a second-class character.”

Of all the drawings in the Art Institute exhibition, The South stands out for the simple genius of its rough construction. As our gaze passes over it, moving from right to left (and we have no choice, as the rightmost word BOOKS is the first thing we see—Steinberg knew that one always reads before one sees), the stuffed toy and guitar in the bookstore’s window plant the first seeds of suspicion. What sort of bookstore sells toys? This prompts further investigation across darkened shops and postbellum buildings, ending at a Confederate monument and a courthouse before one is dumped into a confused, crosshatched tangle of black vegetation. In a single drawing, Steinberg has “read” a southern town and taken the reader backward in time and space to the mechanisms and history behind it—all without depicting directly what the South itself was trying to conceal: the legacy of slavery. Not that he was averse to more direct tactics: later works make free use of a disturbing Day of the Dead–like Mickey Mouse–type character, which Steinberg considered inherently racist: “Mickey Mouse was black…half-human, comic, even in the physical way he was represented with big white eyes.”

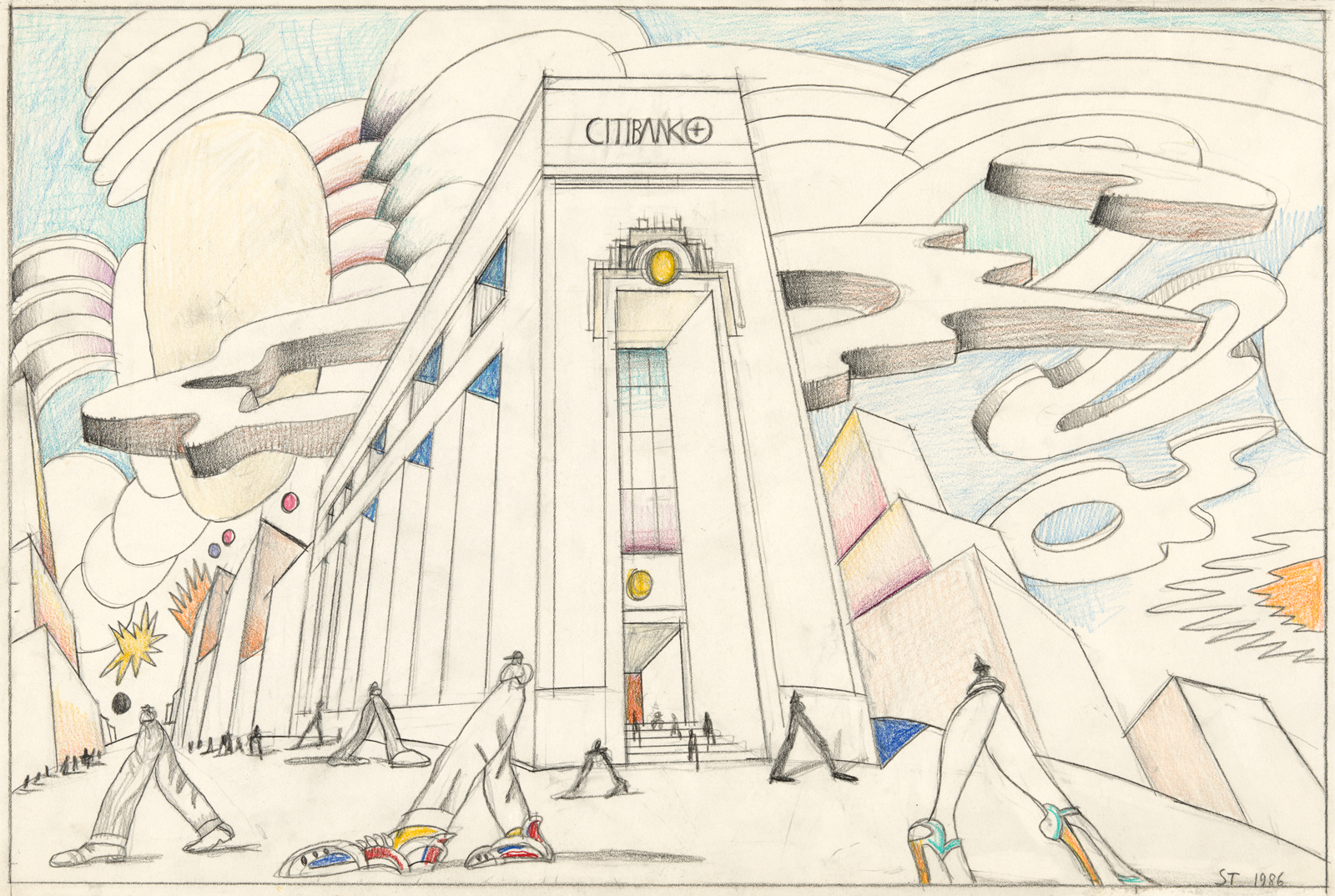

Steinberg’s later work adopts an increasingly dyspeptic view of the nation in which he had taken up residence. Untitled (Citibank) and Untitled (Fast Food) are prescient condemnations of corporate America and the ketchup-and-mustard trickle-down effect of prioritizing appetite over ethics. The artist pulled no punches on this subject, lamenting, “Gastronomy in America, the restaurant, the taste of the nation are governed by the tastes of children.” Like hundreds of Steinberg’s drawings, these two employ a shot-from-the-hip, up-skirt, underfoot perspective of an outsize world: huge legs, skyscraper tops, big shoes. His friend and fellow New Yorker writer Ian Frazier noted in a posthumous reminiscence that Steinberg said “he always tried to draw like a child…the goal was to draw like a child who never stopped drawing that way even as he aged and his subject matter became not childish.”

Advertisement

Really, if one thinks about it, it’s a child’s perspective that grants View of the World from 9th Avenue its power. Ironically, it’s also what most appealed to me as a child, even in the knock-off “Omaha” version I initially encountered. As embarrassing as it is to admit now, growing up in those Reagan years I enjoyed a cultivated blindness to America’s place in our post-war planet, and I think it’s fair to say that I was not alone in this if the television programs of the era are any indication.

Steinberg knew that we are all the functional centers of our own universes. Beginning with an airless blank of empty white, every time Steinberg set his pen to paper, a cosmos exploded through the mnemonic mimesis of his line; not surprisingly, all the works in this exhibition also act in some way as universes unto themselves. While the artist may have preferred, at least early in his career, to see his work in reproduction first and in memory second (which is, really, how we spend the majority of our time with those works of art that most surprise us: thinking about them), each of these drawings also offers a single, signature proof that yes, Saul Steinberg the person really at one point did exist, and, most importantly, that he offered us a view of the world that was both comically unique yet disquietingly universal.

Adapted from Chris Ware’s essay in the catalog for “Along the Lines: Selected Drawings by Saul Steinberg,” on view at the Art Institute of Chicago from May 27 to October 29.