Lubitsch: I heard the name long before I ever saw one of his movies. Adults whose movie-going memories went back to the Twenties or Thirties savored the texture of its syllables, as if it named a circle of delight to which I had not yet been admitted. It was a delight perhaps beyond recapture, enmeshed as it was with nostalgia for a vanished world, steeped in champagne and the melodies of cabaret violinists. “The world he celebrated,” Andrew Sarris wrote in 1968, “had died—even before he did—everywhere except in his own memory.” The Ernst Lubitsch retrospective about to unfold at Film Forum (June 2–15) will offer a most welcome occasion to gauge its dimensions and sample Lubitsch’s very particular pleasures. He offers a parallel domain of buoyant elegance, a theater of free-floating desire and inextinguishable humor ingeniously stitched together out of the fabric of Austrian operettas and French farces and the plot devices of a hundred forgotten Hungarian plays, flavored by delicate irony and risqué innuendo, where sex is everywhere but just out of sight behind discreetly closed doors, constantly implied in what is never quite stated.

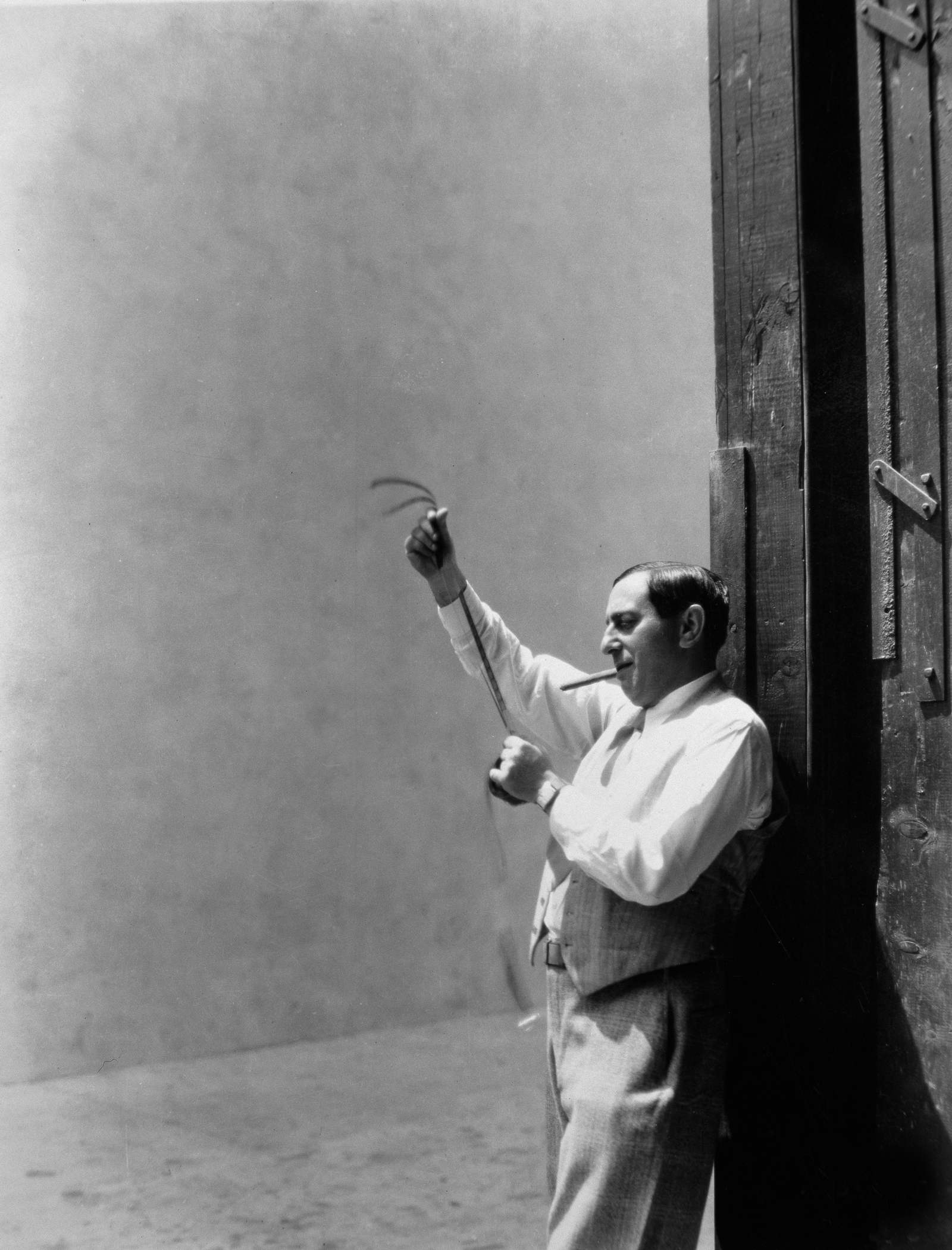

The world conjured by Lubitsch had vanished all the more thoroughly for having never altogether existed to begin with, except as filtered through the imagination and observations of a Berlin Jew, a tailor’s son, with a passion for every form of theatricality and a genius for comic invention. A member of Max Reinhardt’s company at nineteen, he moved on to writing and directing short film comedies in which he also starred. He experimented constantly in early comedies like the grotesquely satirical The Oyster Princess (1919) and the visually audacious The Mountain Cat (1921), with its shape-shifting screen formats, but it was his lavish historical epics Madame DuBarry (1919) and Anna Boleyn (1920) that brought him worldwide celebrity. By 1922 he was in Hollywood where he reinvented himself for American audiences as the purveyor of a “Continental” style steeped in civilized suggestiveness with silent comedies of marriage and infidelity like The Marriage Circle (1924) and So This Is Paris (1926).

He created not only a style but a place, his imaginary homeland: that paradise of sophistication disguised as Paris, Vienna, Budapest, the operetta kingdom of Marshovia, or even eventually as the Gay Nineties American Neverland of Heaven Can Wait (1943). We are always looking back toward some long-lost capital city of joy. In Lubitsch’s films memory is constantly being invoked—his characters are forever dwelling on cherished first encounters, unforgettable honeymoon excursions, the minutiae of tiny freshly recalled episodes that encapsulate the deepest of feelings—but it is always an open question whether these memories are not flights of invention, decorating and orchestrating an exquisite counterlife. Those flourishes—magic feats performed in full view of the audience—become something like a companionable accompaniment, enriching the action with deeper layers of joking and commentary.

For all the rigor with which he explored the possibilities of a purely visual film language—famously replacing witticisms with glances in adapting Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan—he adapted to the coming of sound with a burst of creativity in a succession of musicals starring Maurice Chevalier (The Love Parade, The Smiling Lieutenant, The Merry Widow). Remaking The Marriage Circle as a musical in the underrated 1932 One Hour with You (co-directed, somewhat contentiously, by George Cukor), he livens things up with rhymed dialogue and direct addresses to the audience, not to mention an opening evocation of marital bliss as humorously suggestive as anything in the pre-Code canon. With a screenplay by his frequent collaborator Samson Raphaelson, he attained an unsurpassable perfection with Trouble in Paradise in 1932 (“For pure style, I have done nothing better or as good,” he later acknowledged), a game of deceptions and surprises weaving intricate patterns on the themes of theft and seduction and complicity. No Lubitsch film more fully realizes his wish to make a film like a piece of music, in this instance a sonata of Mozartean grace.

The “Lubitsch touch” had by now established itself as a code name for a naughtiness too refined to give offense yet potentially subversive in its implications. But the famous touch was always more than insinuation brilliantly expressed through wordless gags like the complicated ballet of switched and re-switched place cards at the dinner party in The Marriage Circle, the byplay with canes (So This Is Paris) and swordbelts (The Merry Widow), the opening and closing of those doors upon doors that soon became his trademark. Such devices were merely the most overt punctuation marks of a pointed cinematic language in which every object, every glance, every vocal nuance delineates a pulsating network of crisscrossing inclinations and resistances.

Advertisement

Determined forays and sly evasions, battles for dominance and schemes for retaliation, are executed with unfailing adherence to those forms of etiquette marking the mutually understood border between harmonious decorum and the potential anarchy of unleashed emotion. Consider laughter in his films. There are enough moments of characters laughing to establish a taxonomy: exuberant laughter, bullying laughter, uneasy laughter, self-conscious laughter, polite but clueless laughter, charmingly tipsy laughter, deceptively seductive laughter, the condescending laughter of the one who has just been duped, the self-satisfied laughter of the one who imagines he has succeeded at duping.

His characters constantly observe each other, always imagining themselves one up on the others. There are dupes of every sort in Lubitsch, from Edward Everett Horton’s fatuous businessman in Design for Living (1933) to Sig Ruman and his fellow Nazis in To Be or Not To Be (1942); but his films center around highly conscious and self-aware people like Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins as the high-end thieves in Trouble in Paradise, who inhabit a sphere of sophisticated superiority and presumed moral license. They make their own rules amid a society whose trivial restrictions and regulations constantly impinge on their need to assert their freedom of action. Yet even the cleverest are apt to be duped in their turn, as, blinded perhaps by vanity or lust, one further nuance escapes them. Since they are Lubitsch heroes, they will accept loss as gracefully as triumph.

Back in the 1960s, when I finally began to encounter Lubitsch’s work at first hand, at the Museum of Modern Art and Dan Talbot’s New Yorker theater and occasionally on late-night television, it seemed to embody the most inviting of retro fantasies, a vision of a perpetual coquettishly amusing masquerade party. It would take many more years of viewing to grasp how much deeper those films penetrated, as if Lubitsch had crystallized a form of peerlessly graceful impossibility that only the most single-minded artistic devotion could have achieved. “I am so engrossed by the production of a film,” he told an interviewer, “that I literally think of nothing else. I have no hobby, no outside interests and want none.”

A more melancholy undertone becomes apparent in such later works as Angel (1937), Ninotchka (1939), The Shop Around the Corner (1940), Heaven Can Wait, all the way through to his last film Cluny Brown (1946), a romantic comedy set in wartime England in which hidebound aristocrats and parochial villagers are contrasted with a free-spirited plumber’s daughter and a sardonic refugee intellectual who, as played by Charles Boyer, can be imagined as the director’s rueful and still rebellious surrogate. Among the late films, To Be or Not To Be occupies a place by itself for its singular audacity in enmeshing the Third Reich in the mechanisms of comedy, as exemplified by Jack Benny and Carole Lombard in their funniest performances. Against all odds, and in the face of ultimate brutality, Lubitsch asserts the power of laughter to deflate all forms of grandiosity and unjust authority.

Scott Eyman, in his excellent biography Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise, notes Lubitsch’s sense that “music…was the art upon which the other arts depended.” It was his musical sense of form that enabled him to negotiate the gaps between the painfully real and the giddily fantastic. There are always at least two shows going on: a vaudeville whose stick-figure personages turn out to be fully human, and a record of ordinary human behavior in which the characters turn out to be living according to the rules of a comic skit. The formulas that govern the treatment of comic situations become analogous to those that put people’s lives under pressure from the moment that they desire inappropriately. When the real and the comic collide the result can be a jolt, like the gondola loaded with garbage that interrupts the romantic Venetian vista at the beginning of Trouble in Paradise, or the shock of seeing a sober-faced Jack Benny in full SS regalia in the first scene of To Be or Not To Be. Even his most ostensibly serious films—the antiwar plea Broken Lullaby (1932) or the triangle drama Angel—are structured like comedies. No matter how fast his films move when he wants them to, he often reaches an intimate slowness at the heart of them. The rhythms draw inward until we breathe with his characters.

That intimacy comes to the fore in Angel, a film that failed in its own time and has sometimes been dismissed as an ill-advised attempt to make a weepie in the high 1930s tradition. I would see it rather as a beautiful application of comic style—dry and precisely trimmed off at the edges—to the sympathetic treatment of three rather frail humans caught up in a melodramatic situation. The triangle of self-absorbed diplomat, neglected wife with a somewhat dubious past, and aimless war veteran provides the simplest of structures for Lubitsch to present a series of emotional moments with quite stark restraint. Some obligatory comic scenes in the upstairs-downstairs mode, along with a fine turn by Laura Hope Crews as the keeper of what can be discerned, through layers of Production Code euphemism, as a high-end bordello, only reinforce the muted plaintive mood of the central drama. In true Lubitsch fashion, the conclusion comes about by the action of Herbert Marshall as the suspicious husband walking through a door into another room and coming back to his straying wife to report that he has seen what he has not in fact seen, and then walking out with her through another door toward a tremulously uncertain promise of future happiness.

Advertisement

Here as throughout Lubitsch’s work there is the sense of something made with the greatest delicacy word by word, image by image, cut by cut. What persists is the sense not only of the obsessiveness of his attention to detail in shaping the narrative of each of his comedies of desire, but of the generosity of spirit that impelled his own desire to cultivate a sustained delight. In one of his last interviews, he said: “As soon as someone tackles a big theme with a message we take him seriously and call it art. We appreciate a painting of the crucifixion… whereas a simple Cézanne depiction of a vase and an apple may be far more enduring as art. I believe—and I am not comparing myself to Cézanne—in taking a lesser theme and then treating it without compromise.”

“The Lubitsch Touch” will be at Film Forum from June 2 through June 15.