“IS YOUR LIFE SWEET?” A 1996 work by the Brazilian artist Lygia Pape—LEE-zha PAH-pee—poses the question in black letters stuck into long mounds of white sugar poured across a brown background. The photographs that document it look like close-ups of a slice of multilayered chocolate cake, oozing white icing. By the time she made it, Pape’s career had evolved through two schools of geometric abstraction—Concretism and its less rigid Rio de Janeiro counterpart Neo-Concretism. She had made paintings, sculpture, artists’ books, films, installations, and performance art. She had designed all the packaging for Brazilian biscuit manufacturing giant Piraquê. And she had witnessed the disappointments of democracy and the rise of Brazil’s military dictatorship, which briefly imprisoned her. A retrospective of her work currently at the Met Breuer—her first solo exhibit in the United States—is highly conceptual, drawing on semiotics, architectural theory, and anthropology, but never losing a deep connection with the visceral realities of daily life.

Pape (1927-2004) grew up in the mountain town of Nova Friburgo, a three-hour drive northeast from Rio, amid chattering flocks of toucans and macaws; her parents delighted in classical music and tropical birds. She trained as an opera singer but was too shy to perform. In her early work in the 1950s, she sought to create a visual art that would be “something new, uncluttered, and more attuned to the geometric.” The meticulous Modernist discipline of the small early gouache and enamel paintings on wood and the monochrome woodcuts titled tecelares—an invented form of tecelagems, Portuguese for “weavings”—attest to the influence of Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, who, along with Giorgio Morandi, Alfredo Volpi, Alexander Calder, and Giotto, were the artists Pape described as her favorites in a 1997 interview. But she couldn’t abide the act of painting; she was “allergic to oil paint and automotive paint” and found the process of mixing colors physically irritating.

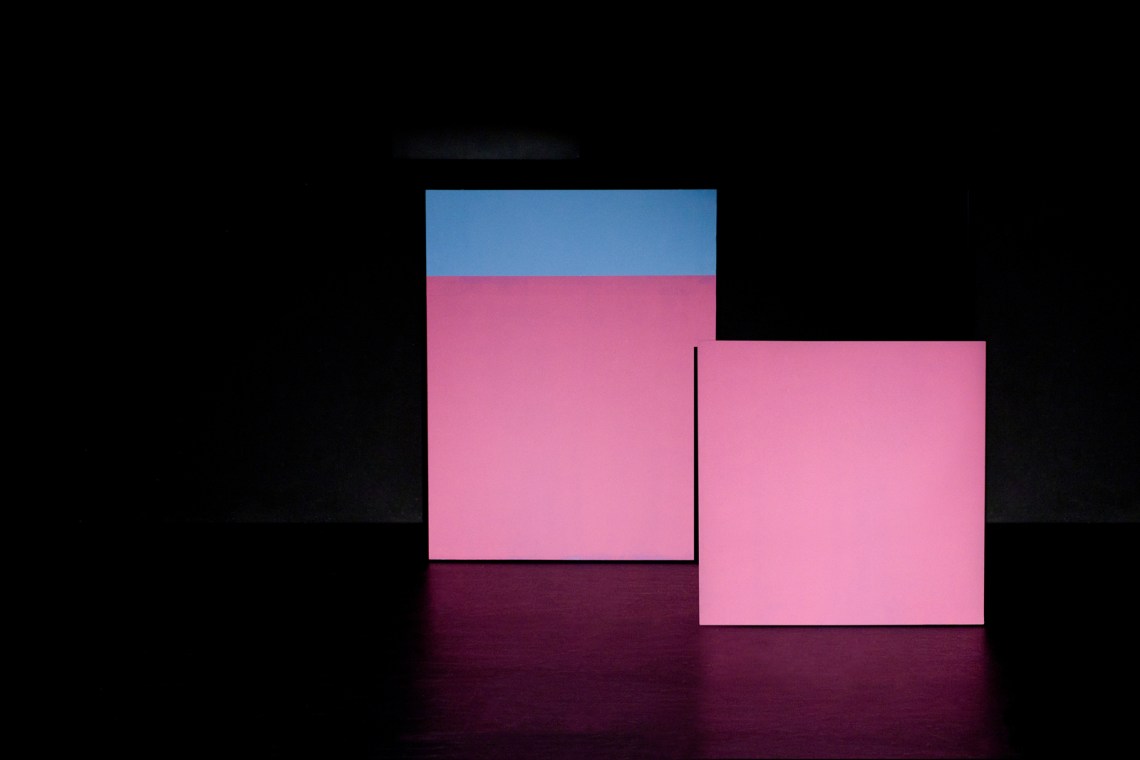

The early geometry remained a constant through her restless subsequent evolution. It morphs into elaborate, wordless books crafted of colorful gouache and cardboard, some of them with pop-ups, cutouts, and fold-outs that viewers are invited to handle and play with. The vast 1961 Livro do Tempo (Book of Time) arrays 365 small square-ish sculptures of tempera-painted wood along a wall like so many maritime signal flags or the logograms of a new, color-based language. The abstraction grows gigantic in her 1958 set design for the Ballet neoconcreto I (Neoconcrete Ballet I), a dance of white cylinders and red square columns that appear to revolve about the stage independently, the dancers who propel them invisible within. And its final glorious reincarnation comes in Ttéia 1, C (an altered form of teia, or “web”), the late masterpiece that expands the early weaving motif into a room-sized installation of golden threads that resembles nothing so much as the slanting columns of light that come streaming down through the upper windows of Grand Central Terminal in photographs taken during the early decades of its existence.

After a 1964 US-backed coup d’état launched Brazil’s twenty-one-year military dictatorship, the subject of appetite became central. The ruthless new regime would eventually drive a number of major figures into exile, including the political activist and art critic Mario Pedrosa, a friend of Pape’s and an influence on her, who left after he was accused of damaging Brazil’s international reputation by informing human rights organizations of torture in its prisons.

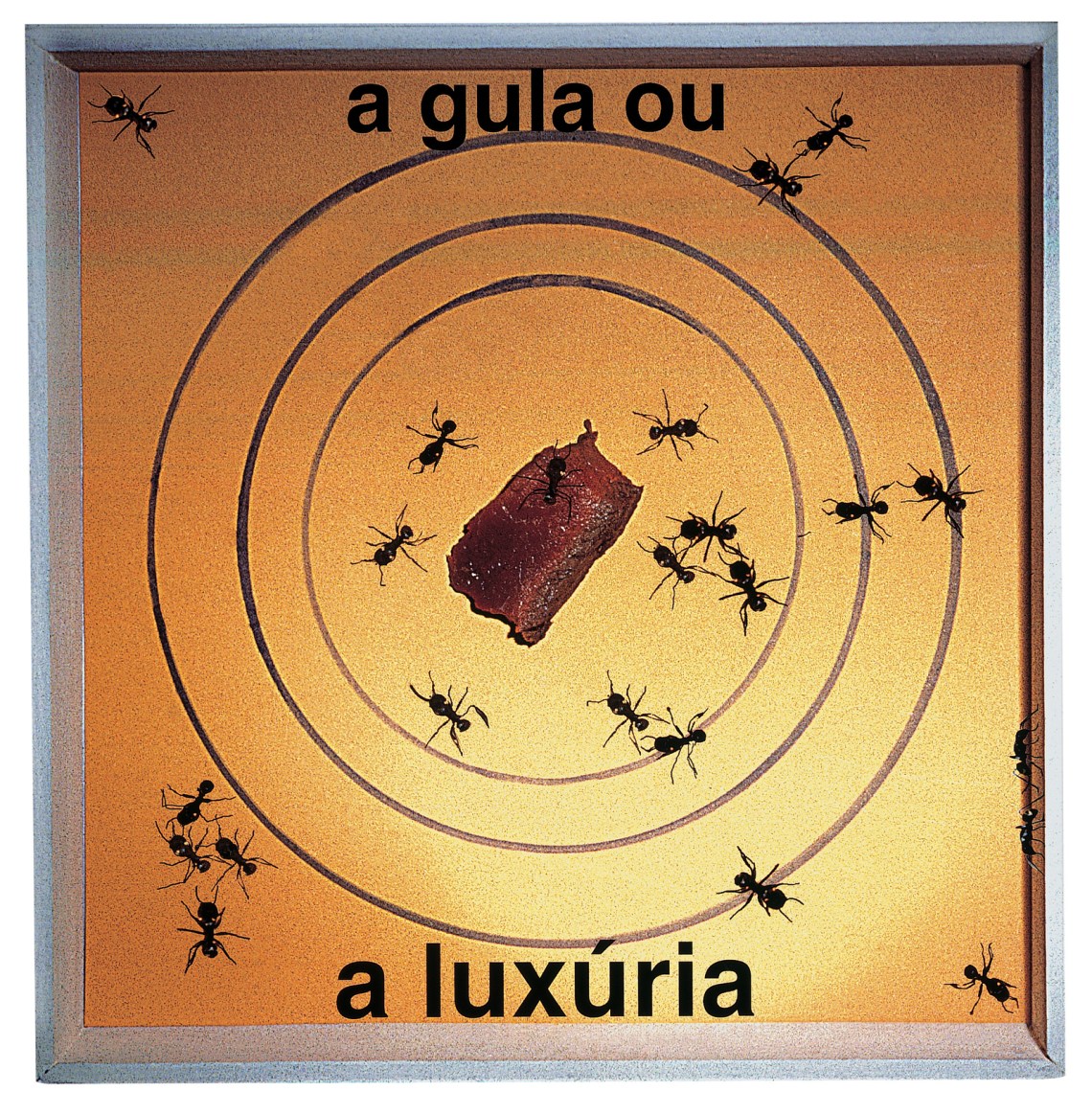

Pape didn’t leave, however, not even after she was imprisoned and tortured for helping dissidents hide from the police. (“Little bird in the cage,” the three policemen with machine guns who arrested her said into their radio.) Her work instead became a quest for forms of dissent that would not immediately be suppressed. A piece in a 1967 show at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro or MAM-RJ (which still uses the logo Pape designed for it) consisted of a Lucite box of live woodcutter ants crawling across a target captioned “a gula ou a luxúria” (gluttony or lust) with a chunk of raw meat at the bull’s-eye. To keep the ants alive, Pape made a small hole in the box, which allowed the occasional ant to get out and stray across the walls and the work of other artists, in tiny testimony to the possibility of freedom, and goals other than those dictated by greed.

On one of my visits to the New York show, two fellow viewers were pushing baby carriages. When the jagged thread of a six-month-old’s cry came through the galleries—a marvelous audible counterpart to works like the Book of Time—I thought at first it might be the soundtrack to one of several film shorts from the 1960s and 1970s projected in the adjacent room, among them a 1974 documentary on Rio’s Carnival that ends when columns of police march toward the revelers. La nouvelle création, made in 1967, was entered in a competition to adapt Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s memoir Wind, Sand and Stars, but the film doesn’t show Saint-Exupéry or his travels. Rather, we see an astronaut moving out into space, connected by the umbilical cord of an air tube and accompanied by a recorded baby’s wail—exploration of the skies as a kind of cosmic birth.

Advertisement

In the 1967 Roda dos prazeres (Wheel of Pleasures), a large table is set with bowls of primary-colored liquids, each with its own medicine dropper. On Sunday afternoons, visitors to the Met Breuer are allowed to partake in this banquet of color and flavor by dripping the liquids—which taste like vinegar, salt, pepper, and other things both pleasant and unpleasant—onto their tongues with the droppers. Pape saw the act of creation as “bestowing new meanings upon forms,” and her work embraces such transformations; in mid-April, the great bowls of liquid looked as if they’d been set out in preparation for some giant’s Easter-egg-dyeing party. But a blown-up black and white image of the artist on the opposite wall serves as a cautionary reminder. Pape is sticking out her tongue and a dark liquid trickles down it; the work is titled Língua apunhalada (Stabbed Tongue, 1968). Such juxtapositions of play and danger are typical; her work often entices viewers with a cheeriness that proves deceptive. “The most radical experience in Wheel of Pleasures would be the use of poison as one of the flavors,” she once told a journalist.

In 1968, while experimenting with the “possibility of an authorless work,” Pape made Divisor (Divider), a forty-square-meter stretch of white canvas regularly punctuated with slits like large buttonholes. Groups of participants—children on the muddy paths of a Rio favela, passersby on streets and plazas in Hong Kong or Madrid, Met museum members on Madison Avenue who signed up for the occasion—are invited to don the work by slipping their heads through the slits and moving around collectively. The experience looks joyously playful, the canvas a collective, gigantic Halloween ghost costume, or a social fabric made literal. It’s easy to forget that Divider is a work of political protest. The Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade’s seminal post-colonial Cannibalist Manifesto (1928) argued that Brazil’s unique strength lay in its ability to gleefully ingest every culture it came into contact with. Sixty years later, after half a decade of dictatorship, Pape’s Divider revisits that tradition. The immense white canvas reads as a tablecloth, and at this banquet, the smiling heads bobbing across it are the guests, the table, and the meal.

“Lygia Pape: A Multitude of Forms” is on view at the Met Breuer through July 23.