In “Taming the Bicycle,” his 1884 essay about learning to ride a bike, Mark Twain described the way that cycling uncovers the secrets of a landscape. “The bicycle,” he wrote, “is as alert and acute as a spirit-level…. It notices a rise where your untrained eye would not observe that one existed; it notices any decline which water will run down.”

Cycling lets you cover territory you might not otherwise be able or inclined to in a way that is faster than walking, more intimate than driving. On a bike the road ceases to be an abstraction on the map but becomes a physical reality. There’s something inherently cinematic about the way you take in your surroundings on a bike, too, with sweeping pans, lingering close-ups, jump cuts as the lights change and you roll into gear. Perhaps one reason there are so few truly great films about cycling (Jørgen Leth’s documentary about the Paris-Roubaix one-day classic, A Sunday in Hell, and Sylvain Chomet’s animated The Triplets of Belleville being notable exceptions) is because the act of cycling—just sitting in the saddle and watching the world roll by—is itself more dynamic than any film can convey.

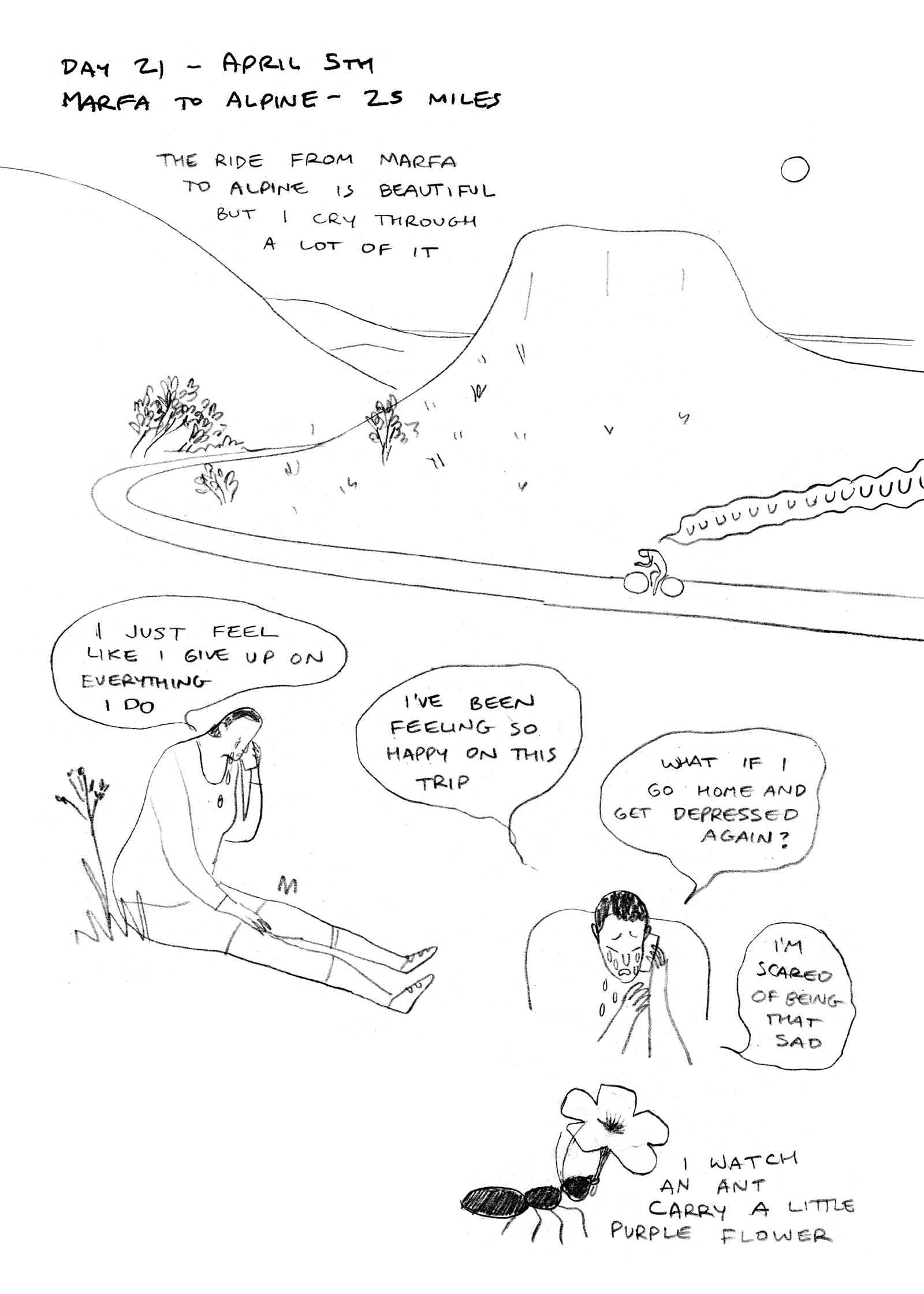

In 2015 the cartoonist and activist Eleanor Davis set off on a bicycle ride from her parents’ house in Tucson, Arizona to her home in Athens, Georgia, a distance of 1,800 miles or so, riding a bike her father had built for her. When people asked her why she was making the journey, she’d tell them that she was thinking of having a baby and so it was now or never. But really, as she confesses in You & a Bike & a Road, her playful, poignant graphic book documenting the ride, “I was having trouble with wanting to not be alive. But I feel good when I’m bicycling.” I worked as a bicycle messenger in London for years, and it was striking how many of my colleagues, many of them mentally unwell, felt similarly. Cycling—the intensity of focus it provides, the joyous fatigue—can be good for the mind as well as for the body.

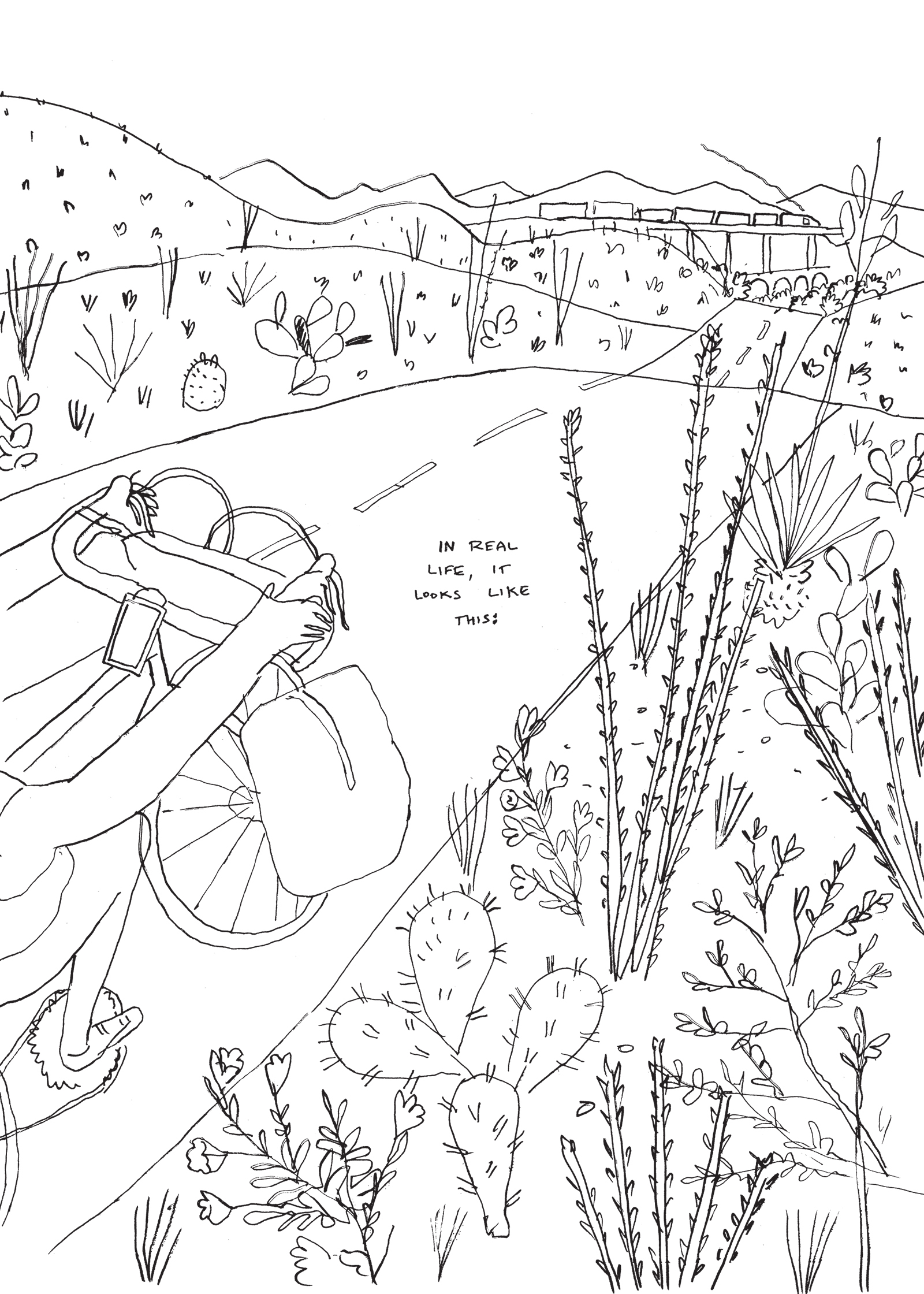

At the beginning of her journey, Davis was most concerned about her knees giving out, and “getting bad hemorrhoids.” She was worried she wouldn’t be able to go the distance, and early on her parents drove out to meet her on the road. “I can’t quit now,” she says at one point, “I’ve already tweeted about it.” But gradually she begins to enjoy the ride; the freedom it affords, the exhilarating self-sufficiency of bicycle and rider acting as one. “I like having everything I need with me,” she writes, “enough food and water to get to more food and water. I like going further than we tell ourselves is possible.”

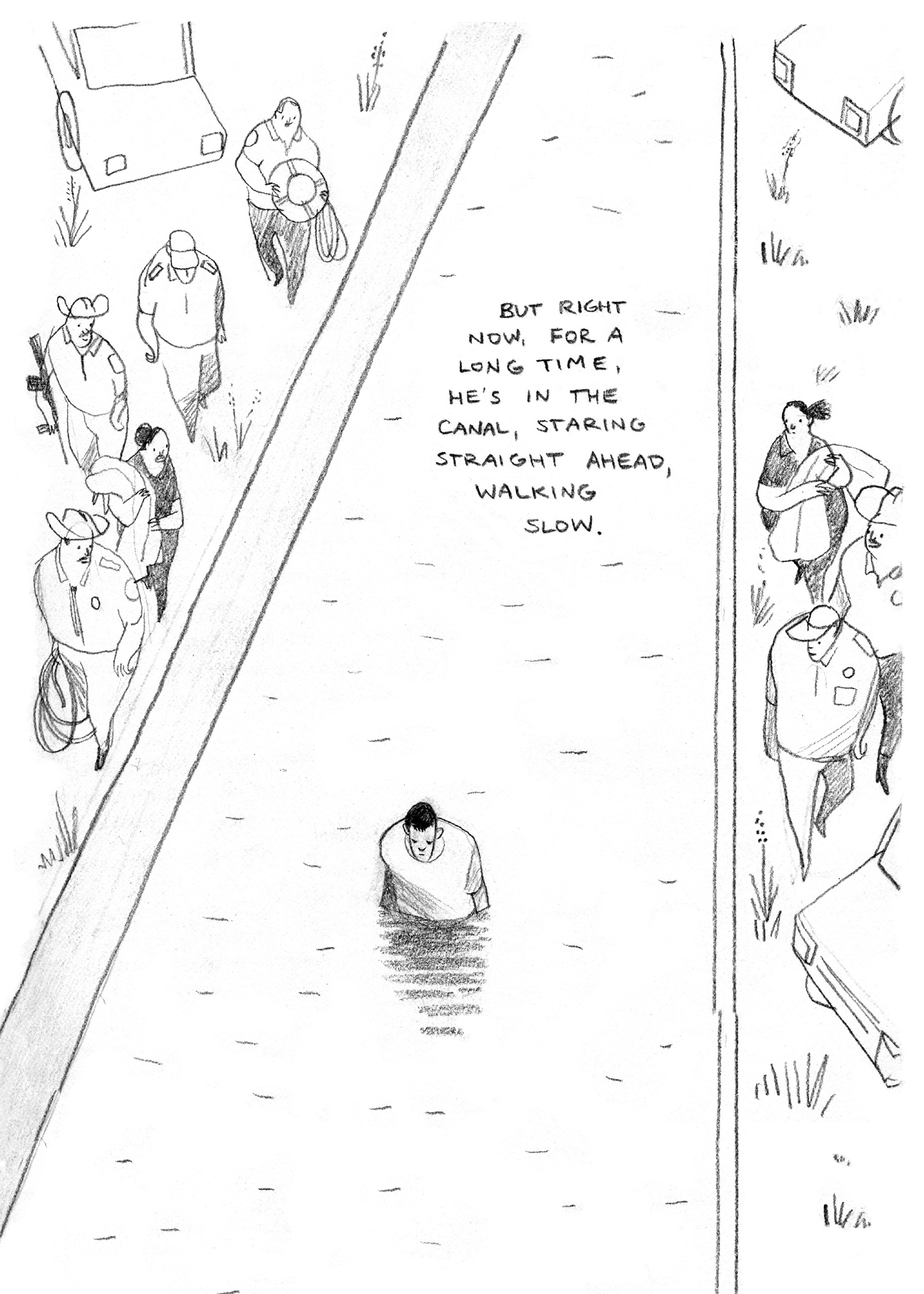

The illustrations—sketched from the roadside during the journey—are charming: simple but evocative pencil drawings, some showing the smudges of the traveling hand, the impress of the snatched moments in which they were created. In their scratchy immediacy they bear witness to things seen and felt. Comics lend themselves to representing how a cyclist sees: the flatness of the bird’s-eye-view map set in contrast to the scene-by-scene illustrations of Davis’s daily experience. We are pulled into Davis’s perspective, seeing from her position on the road as well as from a close third-person view as if slightly above.

A bicycle ride is a good way to get to know people too. In Alpine, Texas, after a particularly tough stretch, she meets a bicycle mechanic who is also a trained therapist. He puts her in touch with a masseuse to work on her aching knees (“Am I gonna do permanent damage to my knees??” she asks him. “Yup,” he replies, “but you love it. You got to keep doing it.”)

Riding along a section of the route of Trump’s proposed Great Wall, she becomes acutely conscious of borders and the people who enforce them. Patrol helicopters buzz above her. They leave her alone when they notice the color of her skin, she notes. At one point she witnesses a man driving to escape the border patrol crash his car into a canal before the police try to lasso him out of it. Later she checks for reports about the event on her phone, as if to confirm for herself that it really happened, as if we can only believe something to be real once it’s popped up in our newsfeeds.

She cycles through a military reserve where the signs are written in Arabic, at the center of which is a Potemkin Afghan town used to train soldiers in urban combat. She is chased by dogs (a familiar hazard for cyclists: the playwright Alfred Jarry, who scandalized Parisian society by wearing his bicycling trousers to Mallarmé’s funeral, used to pedal around Paris letting off a pair of pistols to deter them). At first Davis tries to outrun them. When that doesn’t work she adopts a more friendly approach, which is equally ineffective.

Advertisement

You & a Bike & a Road is a lovely, slow book about going a journey—not an epic, world-dominating circumnavigation, but something quieter and more intimate. It feels truer somehow than many other cycling narratives, those brash accounts of extraordinary human endeavor. Instead it’s a quiet celebration of what Davis calls the “sovereign body” pitted against the landscape and “god’s thrilling indifference.”

Eleanor Davis’s You & a Bike & a Road is published by Koyama Press.