Street photography likes to dress our wicked impulses in dignified clothes: it gawks, jeers, heckles, and points. It rips out whole fistfuls of urban life, only to lay them before us as the righteous truth. Basking in a city’s unrehearsed harmonies and telling clashes, it can reveal something big and necessary about lives that must be lived in public: the lives of people too hurried or oblivious to look into the lens. Walker Evans rode the subway with a camera lodged in his coat, greedily capturing all the anonymous, unaware faces, pleased by their “naked repose.”

Jamel Shabazz is a kind of anti-Evans. Born in Brooklyn in 1960, he has documented New York street life, largely in the city’s black neighborhoods, with a cheerful guilelessness. Many of his subjects pose, even smile. His photographs are usually the result of consent, not a furtive snapshot—so people comport themselves with a bright, willful crispness, rising to the aesthetic occasion. James Van Der Zee, famous for his princely portraits of Harlem denizens in the 1920s and 1930s, is a clear influence. So, perhaps, are Mary Ellen Mark and Louis Mendes, whom Shabazz has photographed. Sights in the City: New York Street Photographs, a new collection of Shabazz’s work from his beginnings in 1980 to the present, was released a few days after an exhibition of his pictures, “Crossing 125th,” opened at the Studio Museum of Harlem. Though there is no overlap between the book and the show—the latter exhibits only his Harlem photographs—both display Shabazz’s wish to honor and flatter, to fashion touching tributes to a certain kind of black, urban life. But politics makes its brutal intrusions; the joy of the pictures, their poignancy and fellow-feeling, is shot through with defiance.

Shabazz worked as a correctional officer at Rikers Island for twenty years starting in 1983, and has shot both inside and outside prison (though none of his prison images appear in the book). Photography, he has said, performs a dignifying function: to people likely to be locked out of the formal economy and drafted to the swelling ranks of the American inmate population, the knowledge that they are personally, indissolubly significant might be a balm.

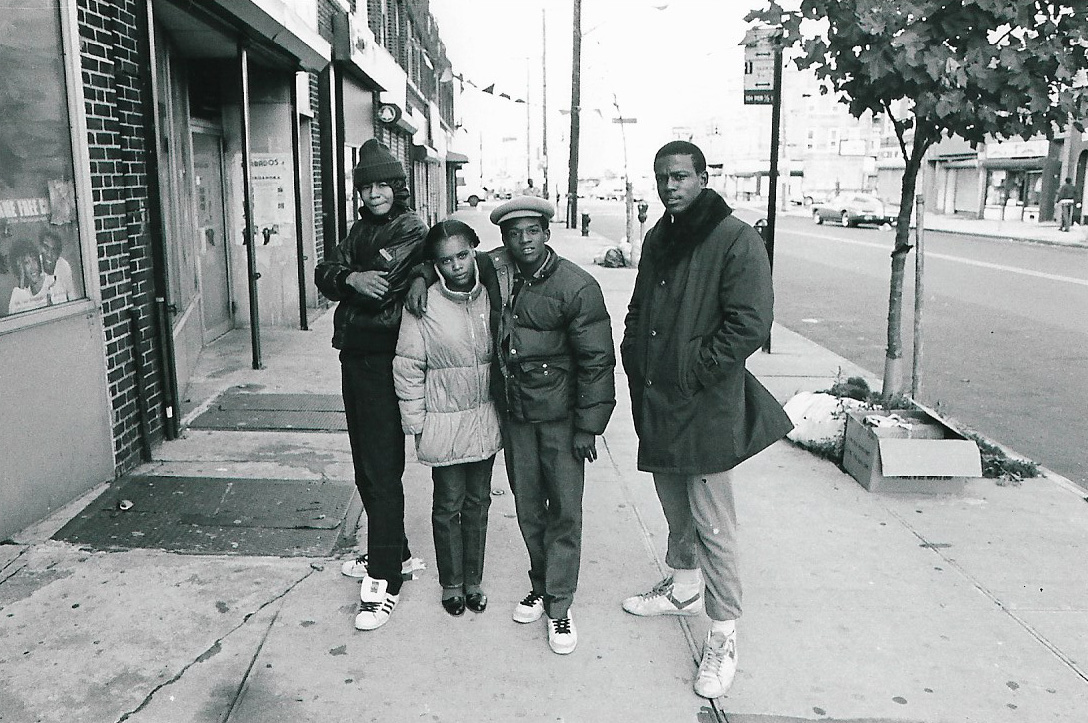

Boys in the Hood (1982, Flatbush, Brooklyn) is blunt and frontal: three men—perhaps older teenagers—frown sternly into the camera, the middle one carrying an enormous boom box. A little boy in the foreground is caught midstride, shattering the picture’s frozen masculinity. A Time of Innocence (1980, Flatbush, Brooklyn) depicts five children grinning in the afternoon haze, some crammed into an abandoned shopping cart. The whimsy of that shot is tempered elsewhere by other, more sullen kids: in The East Flatbush Crew (1980, East Flatbush, Brooklyn) four sneakered adolescents regard the camera with varying degrees of suspicion.

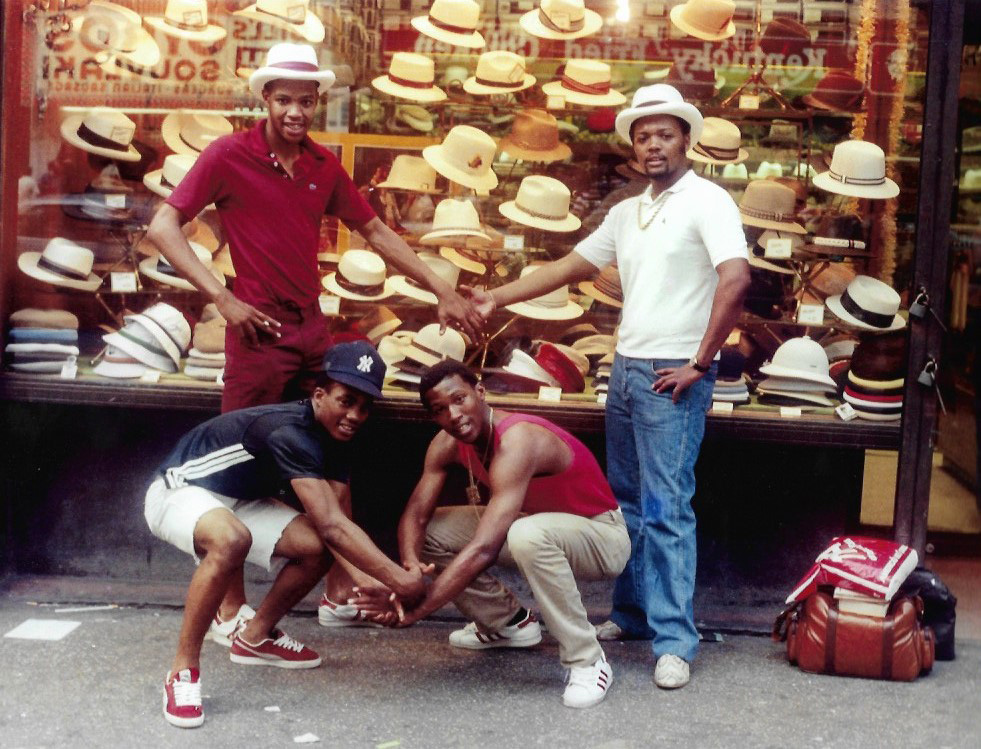

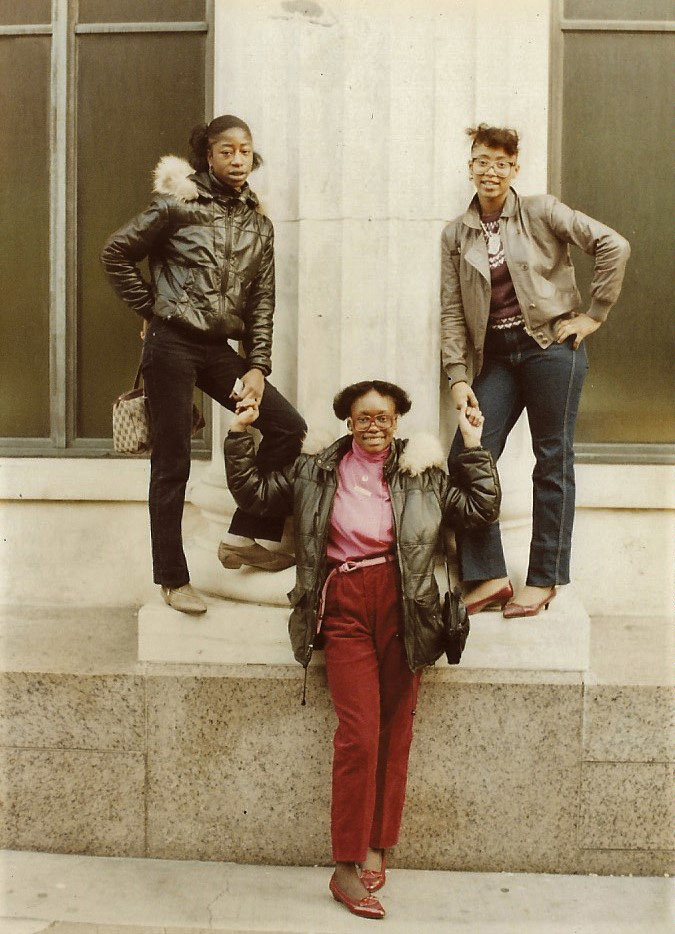

But in Shabazz’s work, exuberance dominates. He began taking pictures in the Eighties; the era’s music, fashion, and social crises seem to drape themselves over his subjects, lending them the prestige of icons. The clothes are extravagant, the colors rich and proud. In Sisterhood (1982, Downtown Brooklyn), three beaming women form a V with their arms, as two stand on the base of a column and grasp a third by her manicured hands. I’m struck by their massive glasses, their high-waisted trousers, the luster of their jackets as they’re hit by the light. Nothing, here, is candid; nor is it feigned. This is a picture of people, but also of their desire, their helpless excitement before the flattery of the camera. The artifice of the shot—its fastidious geometry—doesn’t come at the cost of realism, so much as tease out the composure and performance, the vital, tender postures of city existence.

The pose, then, becomes a kind of civic participation, a relishing of collective life. As the Studio Museum’s wall text proclaims, this show mirrors “the joy, self-determination, and complexities of black life along 125th Street.” I’ll admit that I stumbled on “self-determination”—it juts out from that little litany, shoved forward by historical significance and persistent political demand. So the pose is also about power, an announcement of agency, of the subject’s regal will. That will, however, has a way of turning back to the collective, as life, in Shabazz’s photographs, is there to be observed, snatched up by the passerby or camera-wielding flâneur, such that the struck pose does not mask the truth, but instead reflects the fierce inner need for self-display.

Advertisement

Not, however, for self-exposure. How much to reveal, how much to give to the camera, is a matter of the subject’s private, delicate calculation. You can infer it from the breadth of the smile, the hardness of the pose, the way a body reclines against or lurches away from its backdrop. Each shot is a small social contract between the portrayer and the portrayed: the image emerges from a partnership, a trust demanded and enforced by the photographic ritual.

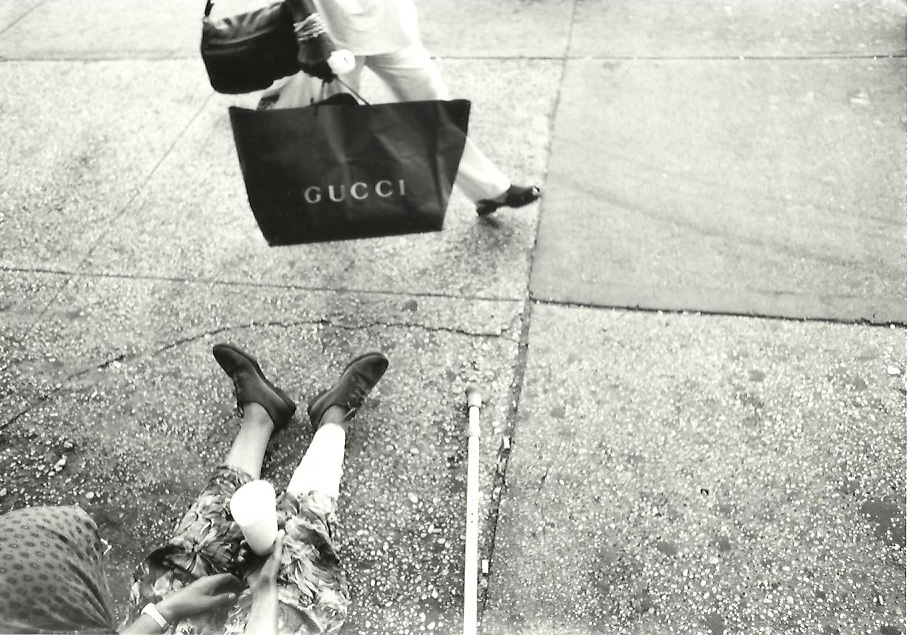

But Shabazz also gives us scenes of tension. Both the museum exhibition and the new book are dotted with pictures of law enforcement. Their political position is unclear—it seems that, from within an inevitable antagonism, Shabazz wants to insist on psychological texture, the miniscule scenes of human drama that resist caricature. That sensibility has aged strangely; the 2017 viewer is left in an odd, clanging political dissonance. Militant pride butts up against the force of the state. In A Time of Protest (1992, SoHo), a black woman at a demonstration is led off by a helmeted cop. In a picture on view in Harlem, four smiling officers pose beneath a sign that gives the work its title: “WE LOVE OUR YOUTH!”

Something else rolls over these images, giving shape and texture to each handsome, studied pose. One wonders how much these men and women, with their elaborate attention to comportment, have been forced to see themselves from the outside: through the lens of a camera, yes, but also through the wide, roving windshields of the city’s armed police.

Jamel Shabazz: Sights in the City, New York Street Photographs is published by Damani and distributed by Artbook DAP. “Jamel Shabazz: Crossing 125th” is at the Studio Museum in Harlem through August 27.