Facing you as you walk into Grayson Perry’s show at Serpentine Galleries, in the middle of London’s Hyde Park, is a huge woodcut, Reclining Artist, showing the artist as his alter ego Claire, reclining nude on a sofa like Manet’s Olympia. Here is the artist-model surrounded by his obsessions: bike parts, images of Alan Measles, his teddy-bear Muse (or, as Perry calls him, his “metaphor for masculinity and God”), and piles of books, including one on Zaha Hadid, who designed the tent-like curving extension to the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, across the river. “I am here, in the center of things,” it seems to say. Is this blatant egocentricity, as sniping critics have claimed, or wry self-awareness? As the title of the Serpentine show suggests—“Grayson Perry: The Most Popular Art Exhibition Ever!”—Perry is always ready to mock his own status. When he dreamed up the title, he writes in the catalogue, “It made me laugh, and slightly nervous laughter is the reaction most art world people have to it.”

Perry’s work is full of bounding energy, an ebullient combination of wit, silliness, seriousness, anger, insight, and compassion. Since he won the Turner Prize in 2003 for his startling decorated pots, he’s come to terms with his insider-outsider status, happily turning out on grand occasions as Claire, with blonde hair, outrageous clothes, bright pink lipstick, and dangly earrings. And if some of the high and mighty are still tight-lipped and disconcerted, the British public have taken him to their hearts, not least because of his openness, his barking laugh, and his ability to listen to people of all classes. He’s proved unfailingly astute in his dissection of contemporary British culture and taste, offering a Hogarthian survey of the nation’s tribes in the tapestries The Vanity of Small Differences and accompanying television series in 2012, delivering the prestigious BBC Reith Lectures in 2013, and making several strange, sympathetic documentaries.

In the art world, Perry believes, despite the blockbuster exhibitions at national galleries, “popular” is a term of abuse, linked to populism and unthinking prejudice. But what’s wrong with more people liking modern art? Near the reclining artist woodcut stands a large pot, Puff Piece, inscribed with critical praise, some real, some invented (the late John Berger cries “Wow,” the critic Jerry Saltz shouts “Genius”). Behind it, another pot, Luxury Brands for Social Justice, in vivid lemons, reds, and greens, is threaded with high-end idiocies like “Flat whites against racism,” or “I’m off to buy a very serious piece of political art.” We laugh, briefly—too much of this can pall—but the casual frivolity signals the licensed joker, free to tell the truth. What should the job of the artist be today, he asks, in our messed up, divided West?

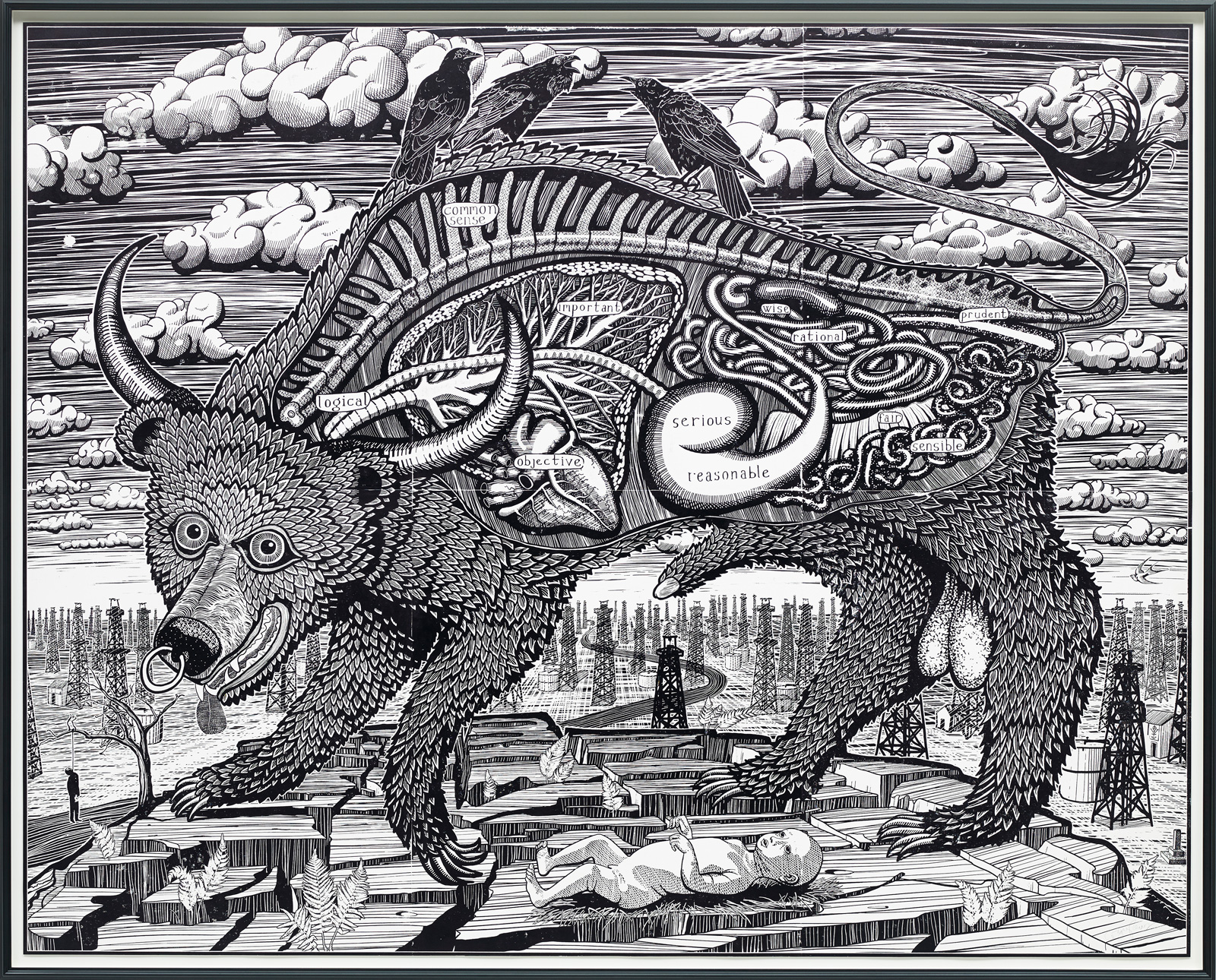

One fantasy answer is the pot titled Alan Measles and Claire Visit the Rust Belt, showing the duo dressed as a 1960s astronaut and wife, with Trump kissing the hand of the teddy-bear—“a traditional hero brought back from retirement to sort out the mess”—and Melania Trump, Nigel Farage, and Marine Le Pen looking on. On the other side Jeremy Corbyn, Theresa May, and Boris Johnson cluster around Claire. Given that Alan Measles is unlikely to descend and redeem us all, Perry suggests elsewhere, perhaps hope can come from looking back at what has happened, understanding the loss and disaster, the outcome of rampant greed. The most striking work here is another massive woodcut, like something from a seventeenth-century tract. A huge bear, its exposed innards labeled “logical,” “important,” “serious,” and “prudent,” strides across a riven landscape against a background of pylons, towering over a hanged man and an abandoned baby. The title is Animal Spirit, a phrase that Perry noticed was often used after the 2008 financial crash, as “a way of offloading responsibility for the human chaos of the meltdown onto some mystical force, when in fact the men controlling the market are as prone to irrational behaviour as anyone.”

The tapestry Red Carpet, a distorted map of Britain, like the topographical work of a medieval monk, presents a diagram of “Them” and “Us” against a background of tower blocks (now a symbol of state and local government cuts and incompetence). The map is afloat with phrases that have echoed through the media in last year: “Millenials,” “good schools,” “extremists,” “obesity epidemic,” “scrap heap,” “zero hours contract,” “mindfulness.”

This is a broadly political show: it opened on the day of the British General Election, and many of the works in it deal with Brexit. This may feel slightly passé now, but Perry ran his own straw poll and his Matching Pair of “Leave” and “Remain” pots reflect his finding that people on both sides had very similar likes and dislikes, “which is a good result, for we all have much more in common than that which separates us.” (Their making was depicted in his television series Divided Britain.) Heartening, though it doesn’t take us very far. But as well as skimming current attitudes, Perry brings back a deeper issue by including in this show the remarkable iron sculpture Our Mother, a cast iron statue of a tired African woman, struggling with a burden of pots and baby, boots and boats and useless modern junk, including a necklace of old mobile phones. Made for his 2011 exhibition at the British Museum, “The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman,” this forces back into the discussion the thorny issues of refugees and immigration, and also our lifelong search for meaning.

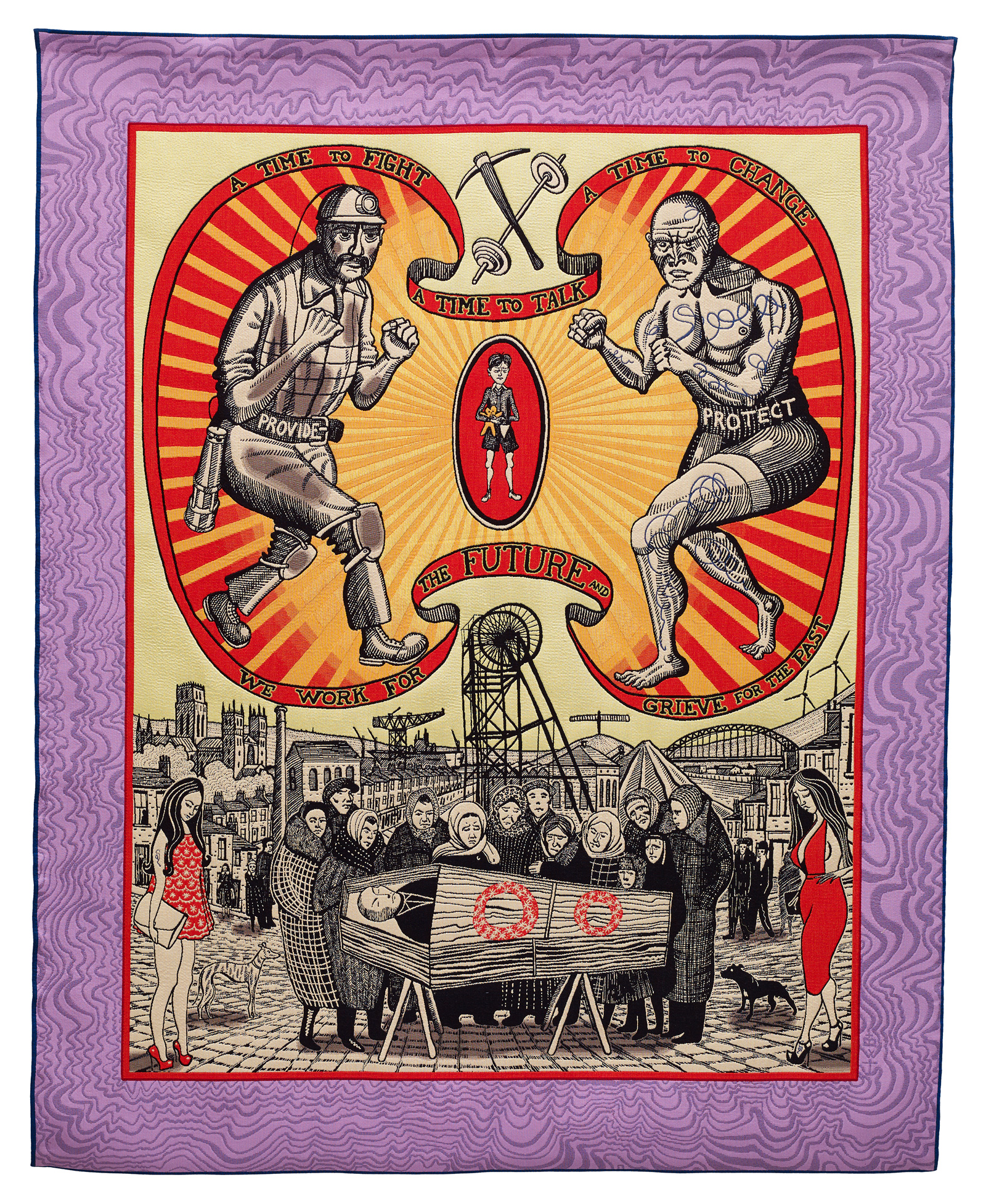

That search underlies his treatment of masculinity, the subject of his 2016 television series All Man. Here the pot Shadow Boxing and the powerful tapestry Death of a Working Hero, based on old Trade Union banners, explore the death of heavy industry in Britain and the worker’s loss of identity. Supplementing these is the darker Digmoor Tapestry, created after Perry met young men in Lancashire, hanging round a 1970s estate, selling weed and fighting rival gangs: “Deprived of acceptable badges of status, job, money, education, power and family, they exercised their masculinity in a way that seemed to echo back to the dawn of humanity—they defended territory.” The same potent feeling of loss emanates from the mysterious cast iron statue King of Nowhere, a stubby St. Sebastian in a baseball cap, pierced head to toe with scissors and knives, standing in a tray of booze.

This all sounds pretty dark, yet it’s invigorating—there’s so much to look at, to point at, to discover. On the day I went, Perry happened to be there, striding about, hair flying, answering questions, explaining, joking, but insisting that however strong the ideas, the aesthetic comes first: “It has to look good.” In the final, large airy room his playfulness dominates. There are escapes and tender moments: the familiar motorbike, built in 2010, in counter-macho blues and pinks, “a kind of Popemobile for my teddy bear”; the curvy, candy-colored women’s bike decorated with a talismanic statue of “Princess Freedom”; the shrine to married love with its statues of Perry and his wife Philippa; the skateboard, or Kateboard, with the Princess of Wales, in the style of a medieval church brass—“the only context where we would get to stand on top of a member of the Royal Family.”

All this, plus the notebooks that show the labor and planning and obsessive doodling behind the works, adds to the show’s dynamism. But the deepest appeal lies in the combination of original concepts and craftsmanship. Perry makes his own pots, but most of his art is collaborative and he’s the first to acknowledge the astounding skill of the foundry workers and tapestry weavers involved. He returns constantly, too, to the people’s art, the folk art of Africa, or of Ruritania and Lithuania, the junk creations of outsider artists—like a totemic Alan Measles made from pebbles and sea-shore debris—and to the banners, and the bikes and sheds and graffiti, of “ordinary people.” It’s here, in showing that craft is also “art,” and that it belongs to us all, even more than in his overt political statements, that Perry is truly democratic and profoundly “popular.”

“Grayson Perry: The Most Popular Art Exhibition Ever!” is at Serpentine Galleries through September 10, and at the Arnolfini Centre for Contemporary Arts in Bristol from September 27 through December 24.