Gauri Lankesh was the editor of a weekly tabloid published in Kannada, the main language of the southern Indian state of Karnataka. She was murdered on the fifth of September at the gate of her house in Bangalore, shot in the head and chest at close range. Her killers got away on motorcycles. This gangland-style assassination of a journalist would have made a stir in any case, but coming as it did after a series of political murders, it resonated across India and beyond its borders.

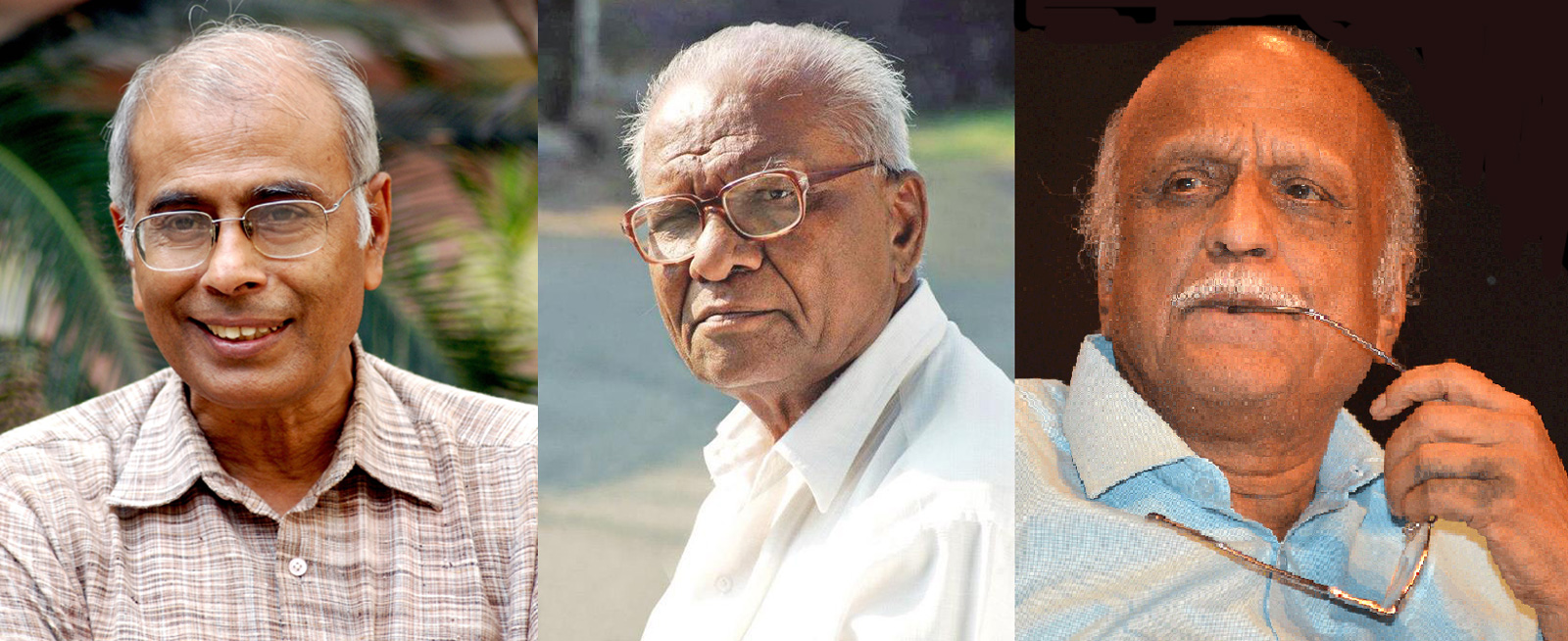

From the moment she died, the press reported her death not as an individual event but as the fourth in a sequence of assassinations; to the names Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, and M.M. Kalburgi, journalists now added Gauri Lankesh. Politically they were all left-leaning, strongly rationalist, hostile to Hindu orthodoxy, and convinced that right-wing majoritarianism was the mortal enemy of republican democracy. They were also public intellectuals who chose to write in their mother tongues: Dabholkar and Pansare wrote in Marathi, Kalburgi and Lankesh in Kannada. They spoke to a vernacular readership beyond the reach of the country’s English media, with its pan-Indian but paper-thin Anglophone audience. Each of them was shot dead by men on motorcycles with homemade pistols who got away.

India has always been a dangerous place for journalists. The Hindi journalist Ramchandra Chhatrapati, who in 2002 first published the anonymous letter accusing Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, the recently jailed cult leader, of rape, was shot and killed weeks after his story ran. More than thirty journalists have been killed in the state of Assam in the last thirty years. In the newly created state of Jharkhand, with its mining mafias, being a journalist is a conspicuously dangerous business: four journalists have died there since 2000 and no one has been convicted of their murders. Malini Subramaniam, a freelance journalist, was hounded out of Bastar in the state of Chhatisgarh by a vigilante group acting in concert with the local police because her reports on the Maoist insurgency didn’t fit the government’s counterinsurgency narrative. In Madhya Pradesh, a central Indian state, a scandal about corruption in a government-administered examination board was dwarfed by the horror of its aftermath: nearly forty people associated with the scandal as culprits or witnesses died seemingly unnatural deaths, and in 2015, a journalist investigating the case the case died in mysterious circumstances.

These incidents are classic examples of violent censorship, of concealment by murder. But the killings of Dabholkar, Pansare, Kalburgi, and Lankesh don’t seem to be instrumental violence designed to silence inconvenient revelations. While it’s reasonable to be concerned about the impact of these killings on free speech and journalism, to see them primarily as an extreme form of censorship is to underestimate the enormity of the crime. Their murders look more like ideological assassinations designed to punish intellectual dissent.

Lankesh was a muckraking reporter and editor who was also a polemical left-wing critic of Hindu majoritarian politics at every level, regional and national. Dabholkar was a rationalist and atheist married to a Muslim woman who had made the debunking of Hindu godmen and their claims his life’s work. Pansare was a member of the Communist Party of India, a lawyer and trade union leader who energetically contested majoritarian readings of Indian history. Kalburgi was an epigraphist and scholar whose special field was the literature of a religious sect in Karnataka, the Lingayats. In the struggle over Lingayat identity there were two sides: a conservative one that embraced brahminical Hinduism and a radical one that saw Lingayats as a distinct minority that ought to resist assimilation. Kalburgi outraged the conservatives; he was threatened, forced to recant his views, and eventually murdered. Gauri Lankesh was, like Kalburgi, a Lingayat, and she took his side in this dispute. She was flamboyantly opposed to Hindutva, the majoritarian nationalism sponsored by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). We don’t know who killed these four—apart from some preliminary arrests no one has been formally charged with any of these murders—but given the uniform way in which they were killed, it’s reasonable to assume that they were punished for their ideological positions.

The intimidation or murder of inconvenient journalists is part of a much wider violent tendency. Since Narendra Modi became prime minister, India has seen a spate of targeted assaults on poor Muslims and Dalits, plebeian groups who deal in hides and skins and cattle and meat. Dalits dealing in cow hides have been systematically thrashed by vigilantes, encouraged by the present regime’s commitment to cow protection. Muslims have been dragged from their homes and beaten to death on the suspicion of having eaten beef. Muslims involved in the cattle trade have been bludgeoned to death on public highways as they begged for their lives, or strung up on trees and lynched.

Advertisement

The deaths of Dabholkar, Pansare, Kalburgi, and Lankesh weren’t just murders; they were lynchings, no different from the killings carried out by cow vigilantes. Middle-class commentators in India sometimes make the mistake of separating violence against intellectuals from violence against working people. Whether all four executions can be laid at one door, or whether their uniform modus operandi indicates copy-cat killings, there is a ritual quality to these murders. They are the Indian equivalents of the machete murders of rationalists and secularists in Bangladesh, where the Islamist right makes public examples of dissenting Muslims, condemned as apostates. Apostasy isn’t a condition generally associated with Hinduism, but Hindutva’s remaking of Indian nationalism in the image of India’s religious majority has helped define it: the self-hating Hindu as anti-national traitor.

The function of political violence is to let bigotry slip sideways into public conversations. Every lynching, no matter how horrifying, becomes, in time, a matter of debate. Gauri Lankesh’s killing was a case in point. Hours after her death, a television journalist tweeted that she got what was coming to her. A businessman from the prime minister’s home state, Gujarat, achieved viral notoriety by tweeting that a “bitch died a dog’s death and set all the puppies yelping in tune.” This was especially notable because Prime Minister Modi followed him on Twitter. And despite the chorused outrage this tweet provoked, Modi continued to do so. What began as a general condemnation of Lankesh’s murder turned into a whispering campaign about her sympathy for insurgent Maoists, her conviction for defamation, her falling out with her brother, and under this sustained, posthumous inquisition, Gauri Lankesh became fair game: a martyred heroine to some, a treacherous virago to others.

Liberals have been accused of blaming the murder on the BJP and its affiliated organizations without a proper investigation or evidence. It is entirely possible that Gauri Lankesh’s murderers had nothing to do with these specific groups, that perhaps it was the position she took on Lingayat assimilation that got her killed. But knowing the identity of her murderers is less important than understanding what they were doing. For the inquisitors who ordered her killing, Gauri Lankesh was a witch. The driveway ambush was a public burning.