What is “an object” in the end? And what is “the world” that these objects make up?

When we talk about consciousness, we rarely discuss ordinary physics, which we assume science has long since understood: objects are composed of atoms; they exist entirely separate from ourselves, and can be measured and manipulated in all kind of ways. It’s also clear, however, that this idea of the physical world works only if we suppose that consciousness—our experience of that world—is distinct and apart from it; objects exist first outside us, then in a secondary, shadowy way as representations inside our brains. This is the so-called internalist view. Yet, in these discussions, Riccardo Manzotti has frequently insisted that there are no representations in our brains. Rather, he has suggested that experience and object are one. But in that case, what do we mean by an object?

—Tim Parks

This is the twelfth in a series of conversations on consciousness between Riccardo Manzotti and Tim Parks.

Tim Parks: Richard Feynman, the winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965, insisted that “Everything is made of atoms … and acts according the laws of physics.” Any object or animal or person is made up of atoms. Thus if we see not atoms but an apple, a star, or a cloud, this is simply our subjective representation of a reality too intricate for us to apprehend. It seems hard to disagree with this.

Riccardo Manzotti: Not at all. This argument was refuted by Democritus as early as the fourth century BCE in a dialogue between the Intellect and the Senses. Let me quote:

Intellect to Senses: Ostensibly there is color, ostensibly sweetness, ostensibly bitterness, actually only atoms and the void.

Senses to Intellect: Poor intellect, do you hope to defeat us while from us you borrow your evidence? Your victory is your defeat.

The view that only the smallest constituents, atoms, are “real” is called smallism in science, or nihilism in philosophy, and it clashes with everyday experience and common sense in the most blatant way. As Democritus suggests, it’s self-defeating because it is conducted only with the aid of the senses, which it claims have no reality. The world we live in is a world of objects. Apples exist, too!

Parks: But an apple is made of atoms.

Manzotti: To be made of something is not the same as to be identical with it. “To be made of” means that if the atoms were not there, the apple would not be there, either. That is something we all agree on. But the apple is something more than the atoms it is made of. The apple—or the car, or the pinstripe suit—exists relative to a human being’s body.

Parks: You spoke of objects existing relative to others in an earlier conversation, but I’m not sure I have really understood. Why relative to a human being’s body and why not simply to a human being? Why not relative to a horse, or a maggot, or a tree?

Manzotti: This is a crucial point, so let’s take it slowly. What is required for an atom to be an atom?

Parks: I’ve no idea. A nucleus. Electrons. I’m no expert on physics.

Manzotti: I mean for an atom to behave as an atom. To function as an atom. To do what atoms do.

Parks: Well, I suppose it needs another atom to combine with. But couldn’t it exist without behaving, or functioning, or doing? In blissful isolation?

Manzotti: Nobody has ever found any atom, or any object for that matter, that was not in a direct cause-effect relationship with some other object, influencing it in some way. To be in such a relationship, something science can measure or experiment on, is what it means to exist. The question of whether an atom could exist alone, in the absence of everything else, is empirically unverifiable, and thus scientifically meaningless. Meantime, though, you are right. An atom, to be an atom, requires nothing more than the presence of another atom with which it can combine. In relation, they are atoms.

Parks: But for some larger object, an atom would not be enough.

Manzotti: Right. A handle, to be a handle, requires a hand. A key, to be a key, requires a lock. A face requires a fusiform gyrus that can distinguish a face from mere skin and hair. For a work of art to be a work of art—Michelangelo’s David, Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby—requires a human being who can see, hear, read. We assume atoms are more fundamental than keys or handles or works of art because they require less work, less stuff, to be what they are. But actually, they are no different from more complex macroscopic objects. Everything is what it is because of its relation to another object.

Advertisement

Parks: And you consider a human being an object?

Manzotti: I deliberately specified a human body rather than a human being because the latter is often taken as a synonym for a self, which is a vague notion and something many people may think of as immaterial. A human body, on the contrary, is entirely concrete. It is another object in the mix—extremely complex, of course, but entirely physical. Works of art need human bodies to exist. If there were no one to read a novel, it wouldn’t be a novel.

Parks: And you would consider a novel an object on the same level as a stone or a beetle?

Manzotti: I am defining an object as something that comes into being by virtue of its relation to another object. In that sense, yes, we can put stones, beetles, and novels on the same level.

Parks: So, just as a novel isn’t a novel when nobody reads it, a stone is not a stone when nobody is around to see it or kick it.

Manzotti: You are hoping to accuse me of Bishop Berkeley’s idealism. Obviously, when I am not there to see or touch the stone, the agglomeration of atoms is there in relation to the ground, the air, or another body, perhaps. But it is not the stone I saw.

Parks: It’s a different object.

Manzotti: Yes.

Parks: With the same atoms?

Manzotti: Yes.

Parks: But don’t we then get back to the formula that reality, minus human beings—objective reality, that is—is simply atoms?

Manzotti: Why would you want to subtract the human beings? We are objects, too, and we make things happen by our relations with other objects. As we said, the conditions for being an atom are simple and ubiquitous. The conditions for being, say, a face are far more complex. But both are real, and both are objects. The reason why people have trouble with these reflections is that we have all been educated to believe that things are what they are in themselves, absolutely. If you take that line, then inevitably you begin to think that only the tiniest universal particle can be entirely real, entirely sufficient to itself: the atom. But as we’ve said, even the atom doesn’t exist alone. And as soon as you accept the widely recognized scientific fact that an object exists relative to other objects, then it’s clear that there are not only atoms, but also apples, cars, and stars. They are all viable objects.

Parks: So how does this change the way we think about consciousness?

Manzotti: We live in a time when scientists seem to like nothing better than to expose our everyday view of reality as delusional. They say, “You see the color red, but in fact, out there are only atoms; there are no colors. You hear music, but out there, there are no sounds,” etc. This gives them the authority to describe an entirely different reality, in which deciding between chocolate or strawberry ice cream, say, is nothing more than a matter of warring cohorts of neurons transferring their electrical charges and chemical processes this way and that, while outside your brain there is only a flavorless world of atomic particles. It’s a vision that denies not only our existence—as people choosing between ice-cream flavors—but also the existence of the things we experience: the banana sundae, a new car, paintings, planets, smells, seas. All these macroscopic objects cease to be real. They are all merely subjective. Merely the product of your brain.

Parks: But what if that’s the truth of the matter?

Manzotti: It is not the truth. It is a profound misunderstanding. The notion that objects exist relative to each other, brought into existence by each other, does not clash with any scientific finding or demonstrated result. Only with smallism, which, again, is an idea, a theory, not a scientific finding. There are atoms, but there are also macroscopic objects, and the key to understanding why both categories exist and are equally real is that they exist relative to different things.

Parks: Can you give me an example of when the same chunk of physical reality is different depending on the object it is in relation to?

Manzotti: This is not hard. My answer would encompass virtually all the objects that make up our lives. The apple is round and red, but pick it up and close your eyes and it is a smooth, hard thing of a certain weight. A different object. Measure the velocity of a car relative to the road, and it is one number. Measure it relative to a second car, and you have another number. Measure the car’s speed relative to a bird, the moon, a passing plane, a distant satellite, and it is different in each case. Velocity is a physical property, yet this property changes depending on the object our car is in relation to. If we have different properties, we have a different object. Because when you see that existence is relative, you also realize that it is multiple; the same stuff, which will always be an aggregate of atoms, can simultaneously be different things depending on what object they are relative to.

Advertisement

Parks: But all you’re doing is describing subjective experience!

Manzotti: The word subjective suggests that a person is somehow inventing what he or she is experiencing, and could perhaps invent it differently. But when I see a red traffic light, I can’t choose to see some other color. The nature of my eyes, my photoreceptors, and my visual cortex is such that when they encounter this phenomenon, it is red. And the red is out there in the street, not in my brain. The color is not a subjective experience, but a relative object. And my experience is the object that, in relation to my body, is that color.

Parks: Sorry: at the traffic light it’s true that almost everyone will see red, but a colorblind person won’t. Surely, he or she is simply seeing it “wrong.” Subjective.

Manzotti: Why wrong? Because in a minority? The body of a colorblind person is no less real than the body of a person with normal color sight, so the objects that exist relative to the colorblind person are no less real than those that exist relative to any human body. But they are different.

Parks: What if we move away from color to something that can be impartially measured by a scientific instrument? For example, a thermometer tells me it’s seventy-two degrees Fahrenheit. I should feel fine, but in fact, I feel cold. At the same time, you’re feeling warm. These experiences, which I assume you would call objects, must be subjective since we know that the temperature is seventy-two degrees.

Manzotti: One of the comedies of modern thinking is that we treat objects that exist relative to the tools of scientists as more real, more correct, somehow, than other objects. In the case you mention, there are four objects: the air, and three others in relation to it—your body, the thermometer, and my body. The thermometer meets the air and says seventy-two degrees. A digit. Your body meets the air and registers cold. My body meets the air and registers warm. All three “measurements” are valid and real. Seventy-two degrees, cold, and warm. You can’t choose to be warm because someone tells you a column of mercury is registering the number seventy-two. There is nothing absolute about the temperature.

Parks: Your point, then, is that we have fallen into the habit of calling objective and real something that exists in relation to a scientific instrument. And we call it subjective and possibly hallucinatory if it is in relation to an individual body that experiences it differently from others. You’re claiming that this is a form of cultural discrimination, not a scientifically useful distinction.

Manzotti: Exactly. And notice, in contrast, how democratic this notion of relative existence is: the average human body, the blind person, the deaf person, the dog, the scientist’s instrument are all equal conditions for bringing an object into existence. As in physics, there are no frames that are more true than other frames, only frames that make it easier for us to compare certain situations. The thermometer simply makes it easy to compare seventy-two degrees with one hundred and ten.

Parks: Has anyone else ever put forward this view of existence as relative?

Manzotti: In one of Plato’s more difficult dialogues, a rather mysterious, unnamed philosopher referred to as “the visitor” or “the stranger” argues that existence is a form of action, of doing things. Since the visitor was from a place called Elea (corresponding to the present-day village of Velia, in Italy, not far from Pompeii), this notion came to be called the Eleatic Principle. It has been restated many times over the centuries, using slightly different terms, by philosophers as diverse as Samuel Alexander, Jaegwon Kim, Trenton Merricks, and Peter van Inwagen. They all connected existence with cause-effect relations between objects.

Parks: Can you give us the mysterious stranger’s exact words?

Manzotti: The reference is The Sophist, 247e: “I say, then, that a thing genuinely is if it has some capacity, of whatever sort, either to act on another thing, of whatever nature, or to be acted on, even to the slightest degree and by the most trivial of things, and even if it is just the once. That is, what marks off the things that are as being, I propose, is nothing other than capacity.”

Parks: It seems hard to get from this fragment to the notion that consciousness is outside our heads.

Manzotti: Perhaps it’s time to ditch the word “consciousness” and simply talk about experience. You’re in the kitchen looking at an apple on the table. It exists qua apple in relation to your body. When you are out of the room, it occupies a space in air; it weighs on the table; it reflects light. But there is no apple. Because what is actually there depends on its interaction with things. Your body is such a thing and when your body is there, an apple is there, too. Not an apple reproduced like a photo in your head. An apple there on the table, in relation with your body.

Parks: So, anything the body experiences as an effect—which is to say, anything it experiences—is an object?

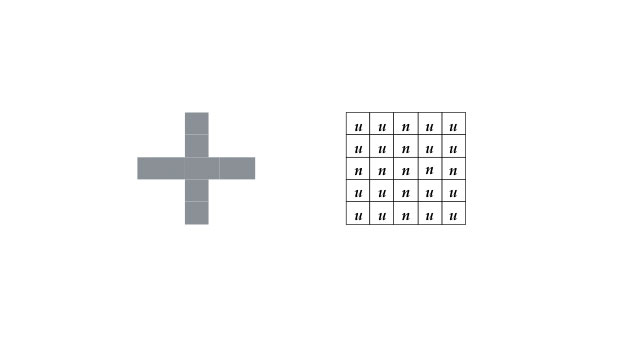

Manzotti: The body does not “experience an effect.” The experience is the apple, which is the cause of an effect. My body allows this agglomeration of atoms to become the cause of an effect in my body. Such a cause is the relative object, the apple, and it is my experience, too. Check out the figure below. How many crosses are there?

Parks: I see only one. There’s a gray cross, and there’s a grid with characters.

Manzotti: Look more carefully: you’ll see that the central horizontal and vertical axes of the grid are all “n”s while the other cells are all “u”s. Look hard and you’ll begin to see a cross of “n”s. The cross on the left is an object that exists relative to a simple state of things: most animal eyes that can distinguish between gradations of gray would perceive it. The cross on the right exists relative to a much more complex object, a human body.

Parks: But do you claim that all experiences, thoughts, memories, dreams—all the things we refer to as mental—are also relative objects?

Manzotti: I do, indeed.

Parks: Even if thoughts are obviously not made of atoms.

Manzotti: Let’s leave that interesting question to our next conversation.