When I was a schoolboy in Britain studying history, one of my classmates asked our teacher to nominate the most incompetent British politician of modern times. Without a moment’s hesitation, he named Lord George Germain, who was from November 1775 until February 1782 the secretary of state for the colonies in the government of Lord North, and so the high official most responsible for the conduct of the War of Independence on the British side. Germain’s hazy knowledge of North American geography, combined with his attempts to micromanage the prosecution of the war from London, contributed heavily to the defeat at Yorktown in 1781, and so to the loss of the war and of the thirteen colonies. But Lord George’s claim to this dubious title is now under serious threat, from not one but four contemporary British politicians.

These make up the quartet responsible for the management of Brexit, the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union that is mandated by law to take place on March 29, 2019. The damage this quartet is inflicting on Britain—its economy, its foreign relations, the ties between its constituent nations, and, above all, the lives of its people—is on such a scale that it is necessary to reach back to the late eighteenth century to find a similar disaster. The Brexit quartet comprises Prime Minister Theresa May, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, Liam Fox, and David Davis (that latter two the secretaries respectively for International Trade and “Exiting the European Union”).

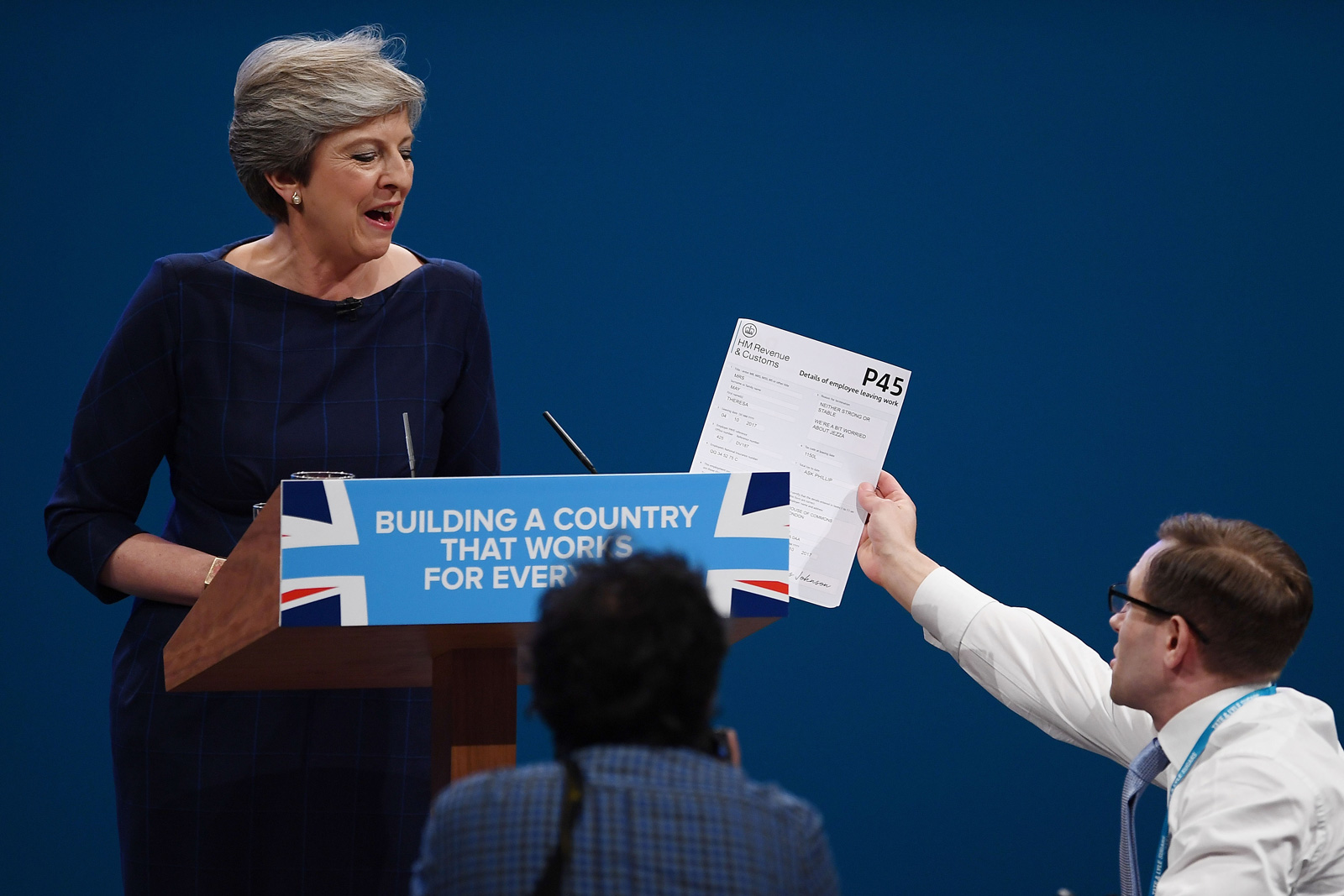

The critical development in Britain’s descent toward chaos has been the collapse of May’s authority after her dismal performance in the general election in June. This was followed by her mishap-prone appearance at the Conservative Party’s annual conference in Manchester last week. There, in a Larry David moment, she was completely thrown, mid-speech, by a prankster who managed to reach the speaker’s podium and serve her with the British equivalent of a pink slip. Her fall from grace means Brexit is even more likely to end badly for the British side.

The UK’s formal proposals for its final Brexit settlement with the EU have not changed since May first revealed them at the 2016 Conservative Party conference, and then elaborated them in her January 2017 Lancaster House speech in London. On the face of it, then, the outcome of the election has had little impact on the British approach to Brexit. But it has changed everything. In her January speech, ahead of the parliamentary vote on Article 50 triggering Britain’s departure from the EU, May announced her intention to withdraw the country from the European single market and the customs union.

But right after announcing these two departures, and in the very same speech, May turned on a dime. She told the assembled EU ambassadors that, following Brexit, she wanted to propel strategic sectors of the UK economy right back into the single market and the customs union, but with one big difference she called her “bespoke” deal. While Britain would still enjoy most of the benefits of membership—“frictionless trade,” in her words—the UK would be largely free of its obligations. So, no free movement of labor between the UK and the EU, no British jurisdiction for the Europe Court of Justice, and no multibillion-pound annual payments by the UK into the EU budget.

This is still the British position, one accurately described by Boris Johnson as “having our cake and eating it,” and by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel as Rosinenpickerei, or cherrypicking—an approach unacceptable to the EU side. But there is a big difference between the iteration of this strategy by May before the election was called, and its iteration by her now. Then, May was thought to be a powerful leader, likely to win a landslide victory in the election that would empower her still further. The genesis of her Brexit diplomacy should be seen as a manifestation of this presumed power.

May put together her approach with only a couple of advisers in Downing Street, and without significant consultation with either her cabinet or British business leaders. But May’s fall has blown open the politics of Brexit within her cabinet. In her year of power, the contradictions of her Brexit diplomacy could be taken as evidence that she needed to make a choice between them, a choice that was hers to make. The weakness of her position now means that these contradictions have been exposed and are harnessed to rival cabinet factions fighting for supremacy, with May caught in the crossfire and powerless to control them. The most significant development in this opening-up of the politics of Brexit has been the emergence of a cabinet faction led by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond.

Hammond’s goal is to salvage as much as he can of the UK’s trading ties with the EU from the crippling damage that the “hard Brexit” side of May’s plan, leaving the single market and customs union, would inflict. Hammond is an improbable participant in what is becoming an intensely political conflict. Of him it can be said, as Donald Trump said of Jeb Bush, that he is a low-energy politician who exudes the complacency of a self-made businessman from the suburbs insulated from the financial struggles of daily life—a characteristic Hammond himself was foolish enough to highlight at a recent meeting of Conservative MPs.

Advertisement

But Hammond’s authority does not stem from his hold over the Conservative Party in parliament or beyond; he is no populist. His position draws strength from the relentless drumbeat of warnings from British and foreign businesses that if the UK cuts itself off from the single market and customs union in a hard Brexit, they will begin moving their UK-based offices and plants to the EU and cutting their investments in the UK. It is now virtually impossible to open The Financial Times without coming across these warnings. On consecutive days recently, the paper reported that “the quiet drift of banking jobs to the EU27 is already under way,” and that UBS was “to shift staff if no transition deal [is reached] by March.”

Boris Johnson leads the cabinet faction agitating for a hard Brexit, a “clean break” from the EU, but he now has a serious rival for leadership of the party’s nationalist wing in Jacob Rees-Mogg, a deeply Euroskeptic member of parliament who outshone Johnson at the recent conference in Manchester. In their different ways, Johnson and Rees-Mogg both evoke the image of late-imperial Britain to which the aging membership of the Conservative Party feels drawn. So what would the great social geographer of the period, Evelyn Waugh, have made of the them?

He would surely have spotted Johnson as a phony in a trice: his combination of bombast and faux bonhomie, his opportunism, his hack writing and intellectual sloppiness. Johnson makes a perfect fit for a villainous journalist toiling away for Lord Copper in Scoop. Waugh would surely have approved, however, of Rees-Mogg’s catholic dogmatism and his ample progeny. In his later years, Waugh complained that the Conservative Party hadn’t put the clock back five minutes; Rees-Mogg is someone who wants to put the clock back sixty years, at least.

For the moment, though, it is Johnson, not Rees-Mogg, who leads the Brexit jusqu’au-boutistes. May has had her opportunities to dispose of Johnson. She could have fired him in January when he likened the approach of France’s then-president, François Hollande, to Brexit to the sadism of a Nazi guard in a World War II prisoner-of-war camp, and again in May, when he drew parallels between the pan-Europeanism of the EU and the Third Reich. These remarks destroyed whatever credibility Johnson had, as foreign secretary, with the other EU governments. It is reported that the German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel cannot bear to be in the same room as him.

But May did not fire Johnson because he has maneuvered himself into becoming the champion of the nationalist insurgency in the Conservative Party and of those voters who see Brexit as a moment of liberation. Johnson enjoys support not only among grassroots party members but also in May’s cabinet, from ministers like Davis, Fox, and the Environment Secretary Michael Gove, along with the militant core of Conservative members of parliament for whom Brexit has been a lifelong cause. Their cause is also cheered by the pro-Brexit national press led by The Daily Telegraph and The Daily Mail. With a gravely weakened prime minister caught between these warring cabinet factions, it is hard to see how their conflicts will be resolved.

The most pressing task for Britain is to set up a temporary trading regime with the EU. This would come into effect the moment the UK leaves the EU, in 2019, and last until the moment, probably years later, when a final agreement between the two sides is implemented. In her year of hubris, May, backed by her Brexit secretary, Davis, was confident that the negotiations for a final settlement between the two sides would be completed by March 2019, allaying any need for a transitional arrangement. But it is clear that negotiations for a final settlement will last well beyond that deadline, so there has to be a transitional deal with the EU to prevent the UK from “falling off a cliff” into a trading limbo, with disastrous consequences for the economy.

The British side is now under intense pressure to conclude an agreement within months. For a business leader like Terry Scuoler, the chief executive of the Engineering Employers Federation, a lobbying group for British manufacturers, the deadline is urgent: “It is vital for business that a comprehensive transitional agreement is agreed before the end of the year… to avoid significant boardroom decisions going against UK plc.” But the divisions within May’s cabinet make it highly unlikely that they can reach a transitional agreement that is also acceptable to the EU side on this timetable.

Advertisement

In July, Phillip Hammond took advantage of May’s absence on vacation to push for a transition agreement that did have a reasonable chance of being accepted by the EU side. His proposal amounted, in effect, to ensuring that the UK’s relations with the EU would continue exactly as before during a transition of several years after the March 2019 deadline. But since July, the Brexit faction in the cabinet has been picking away at the Hammond plan, raising objections wherever it can.

So, how long should the transition last? Should the UK remain in the single market as well as the customs union during the transition? Must the UK conform to new EU regulations enacted during this period? How far should Liam Fox be authorized to go in negotiating trade agreements with third parties? And what will be the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice? With so many issues in dispute, Hammond’s chances of getting his benign, painless version of the Brexit transition are slim to nonexistent.

Amid the gloom, there is one ray of hope. The Brexiteers have always argued that the outcome of the June 2016 referendum represented the unshakable will of the people. But that is in doubt. In a poll taken just before the referendum, a large majority of respondents said that their support for leaving the EU was conditional on its being economically painless. Asked if they would be “happy to lose any of their own personal annual income to tighten the control Britain has over immigration”—a central goal of the Brexiteers—68 percent answered that they would not be prepared to sacrifice a single penny of their income. A poll in July showed for the first time that if a second referendum were held, the Remain side would win, with 54 percent of the vote to 46 percent for Leave.

It now seems unlikely that the UK government will secure a transitional agreement with the EU in time for businesses to postpone their plans to start leaving the UK or cutting their investments there. If so, the percentage of British voters who come to realize that Brexit represents a real threat to their jobs and incomes can only grow. Even affluent Londoners are worried by recent news of falling house prices there. If the last year and a half has revealed anything about British politics, it is the instability of public opinion. If the polling numbers start to move strongly against Brexit, the political class will surely take note and start moving toward the only solution that makes sense for Britain: to abandon the whole disastrous project altogether.