Soap has been at the center of some of the most visceral private and public expressions of racism in South Africa. For all the “apart-ness” that the government tried to enforce through both “grand apartheid” and “petty apartheid,” which worked to control the public interaction between black and white bodies in public toilets, benches, trains, buses, swimming pools, and other facilities, a contradictory intimacy developed in everyday private interactions as black people still labored, and even lived, in the workplaces, kitchens, nurseries, bedrooms, and bathrooms of white South Africans. The uses—and alleged non-uses—of this ordinary household item are thus entwined in the country’s history.

In Rian Malan’s 1994 memoir about his upbringing during apartheid, My Traitor’s Heart, he recalls his intrusion on a live-in black domestic worker:

I tapped an iron door and the black woman opened it, wearing a satin nightgown…. The room smelled of all the things I associated with servants—red floor polish, putu [maize meal], and Lifebuoy soap… then I was in her arms, overpowered by the smell of her, and terrified, utterly terrified… I recoiled at the thought of French-kissing her, but I did it anyway, because I was a social democrat, and I did not want to insult her. And then I pulled up the nightie and instants later it was over.

In this troubling scene, Malan’s mixture of desire and revulsion at the intimate smell of the unnamed black woman’s body is typical of what the literary critic and academic Njabulo Ndebele has called a “fatal intimacy” between black and white South Africans. The novelist Nadine Gordimer, describing how Gideon Shibalo, a black artist, frequented the private world of Johannesburg’s white liberal set in Occasion for Loving (1963), put it this way: “Every contact with whites was touched with intimacy; for even the most casual belonged by definition to the conspiracy against keeping apart.”

I was reminded of this recently by the furor that erupted over a Dove soap advertisement on the company’s Facebook page—a controversy that quickly went viral on social media, including in South Africa. In the ad, a black woman takes off her brown T-shirt, ostensibly after using the product, and, by video-editing, appears to turn into a white woman wearing a lighter T-shirt. On Radio 702, a middle-class Johannesburg-based talk radio station, one white caller phoned in to say that he didn’t understand why the ad should be seen as racist. What was the big deal? The ensuing debate largely centered on the history of racist soap advertisements and the phenomenon of skin-lightening; it did not make explicit Dove’s connection, by way of its parent company Unilever, between modern-day South Africa and its Anglo-Boer/Dutch roots in the colonial and apartheid eras. As I listened, I thought it curious that this caller would exhibit such amnesia about the not-distant history of his country’s racism involving soap and the perceived uncleanliness of black bodies.

Many older South Africans would still remember the notorious “swimming pool” episode that made national news in 1990, during the period when the last president of the apartheid era, F.W. de Klerk, was introducing gradual reforms. In the week after the repeal of the Separate Amenities Act, The Weekly Mail sent Philip Molefe, a black reporter, to the northeast town of Ermelo along with a white colleague. Of all the resistance to Molefe’s use of previously segregated public facilities, the fiercest confrontation took place at the public swimming pool. Ermelo’s enraged white swimmers tried unsuccessfully to prevent him from getting into the water. “While Molefe splashed around,” The Weekly Mail reported, the white lifeguard “screamed angrily, ‘Swim. De Klerk said you can swim… I’ll give you some soap to wash with.’” Later, at another stop, an Afrikaner man muttered, “This place is going to be dirty now.”

Writing in Lifebuoy Men and Lux Women: Commodification, Consumption and Cleanliness in Modern Zimbabwe (1996), Timothy Burke, a professor at Swarthmore, cited this “Ermelo incident” to illustrate the similarities between the former settler colonies of Zimbabwe, where I was born, and South Africa, where I was raised. When I went to a multiracial boarding school nearly fifteen years after the repeal of the Separate Amenities Act, my black friends and I discovered that our white friends were not nearly as religious as we were about showering and grooming. Weren’t we supposed to be the “dirty” ones? We quickly learned that this wasn’t the case, and would often secretly make fun of their hygiene habits: This one doesn’t use a waslap [washcloth] to wash herself, that one sleeps in her clothes, this one didn’t wash after going swimming, that one doesn’t even wash her own panties. For us, our twice-daily showers and hours spent preening were part of the basic “body management” that we’d been taught by our parents, who would preach that “cleanliness is next to Godliness.”

Advertisement

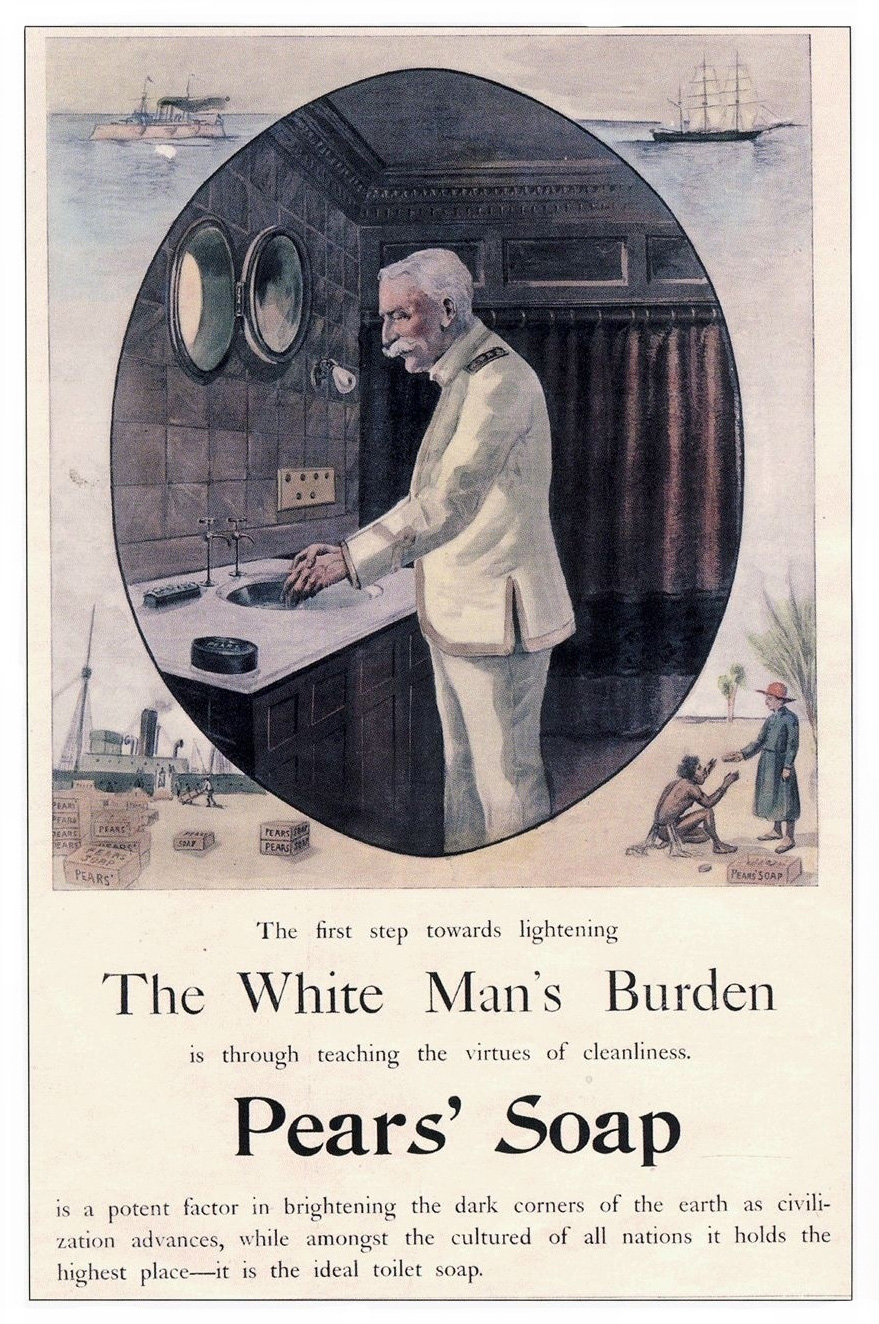

“Soap,” Burke writes, “while having been seen as a fundamental need by most Africans since at least the 1950s, has been closely tied to the practices of cleanliness and domesticity promoted first by missions and the state and later powerfully and massively reproduced in postwar advertising.” As part of a colonial vision that required, in Burke’s words, “properly disciplined bodes,” the promotion of “modern” hygiene had soap at its center. Under apartheid, even household goods were segregated, with companies marketing their products differentially. So some brands, like Lifebuoy, Palmolive, and Lux, were at first used predominantly by white consumers, while others, like Sunlight and “blue-mottled” varieties, became a nearly universal presence in the everyday life of black people in Southern Africa.

In particular, the Lifebuoy soap that Malan refers to in his memoir became an institution in black households, and many older black people would recall the long-running advertising slogan: “After a hard day’s work, Lifebuoy smells nice.” Its message was simple: a soap to cater to the needs of the laboring black body. Another Nadine Gordimer novel, July’s People (1981), reminds us that this kind of message reached white employers, too. July, the servant of a liberal white family, the Smales, “began that day for them as his kind has always done for their kind… [with] the tea-tray in black hands smelling of Lifebuoy soap”; and the same July wore “clean clothes [that] smelled of Lifebuoy… bought for them—the servants.”

When I think about those laboring black bodies in white homes, this “fatal intimacy” seems strange and contradictory: If black people are so repulsive that you require this apartheid, why have them in your homes? If black people are so dirty, why have them cook your food, wash your clothes, raise your children? In her short-story collection Living, Loving and Lying Awake at Night (1991), the South African novelist Sindiwe Magona describes a black domestic worker expected to handle her white “medem’s” intimates:

There, swimming, afloat in that water of hers, was her panty… she’d left it there for me to wash.

What? Me? I taught her a lesson, that very first day. I took something, a peg, I think, and lifted that panty of hers and put it dripping wet, to the side of the bath which I then cleaned until it was shiny-shiny.

You think she got my message? Wrong. Doesn’t she leave me a note: “Stella, wash the panty when you wash the bath.” …

I did not go to school for nothing. I found a pen in her bookshelf and found a piece of paper and wrote her a note too: “Medem,” I said in the note, “please excuse me but I did not think anyone can ask another person to wash their panty. I was taught that a panty is the most intimate thing… my mother told me no one else should even see my panty. I really don’t see how I can be asked to wash someone else’s panty.”

That was the end of that panty nonsense.

“That panty nonsense”: a symbolic phrase for how relations between black and white people in South Africa have been so historically rife with contradiction—apart, yet so deeply entwined. From across the Atlantic—in a North American settler colony in which another system of enforced racial segregation took place, where there exists a similarly “fatal intimacy” between black and white people—Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison observed in 1995: “For three hundred years, black people lived in the segregationists’ houses, were all up in their food, in the intimate lives of their family, and understood that our presence was not repellent but, in fact, sought after—as long as they could control us.”

And here is the crux: control. The development of the “fatal intimacy” relied, in both the United States and South Africa, on the control of the black bodies that labored to build these countries—and a corollary fear of these same bodies’ uncontrollability developed. It is that anxiety that fuels demands for “properly disciplined bodies,” through a range of visual symbols, including the Dove advertisement’s ostensible whitening of black skin. Perhaps that’s what that Radio 702 caller would like to forget: the long history of “fatal intimacies” that created fears so overpowering that commodities as banal as soap can become instrumental in the symbolic control of the uncontrollable black bodies in their midst.