“Items: Is Fashion Modern?” is the Museum of Modern Art’s first fashion exhibition in over seventy years. Borrowing its name from the museum’s 1944 show “Are Clothes Modern?,” the exhibition displays 111 pieces—including clothing, shoes, accessories, and cosmetics—with encyclopedic organization. While the 1944 exhibition, curated by Bernard Rudofsky, considered dress “as though it were an utterly new phenomenon,” the focus of “Items” is far more quotidian. The haute couture one might expect to find at a big fashion exhibition is largely absent. The viewer is more likely to experience recognition and familiarity than vicarious glamour and awe. Distressed Levi’s 501 jeans are framed behind glass, a pair of white Calvin Klein briefs fit snugly on a mannequin, and a collection of multicolored ballet flats fills a vitrine. You might find yourself wearing the same shirt or shoes as those hanging on the gallery wall.

The concept of “modern” in “Items: Is Fashion Modern?” means something different than it did in 1944 at the height of modernist art and style; in “Items,” it refers less to a period of time than to a way of relating to time itself—of dealing with and mingling the past, present, and future. The show features items that have been invented anew, used for present needs, or re-appropriated self-consciously to signal one’s identity, for political purposes, for nostalgic reasons, or simply as irony. These items are displayed in an almost clinical manner, like specimens to be considered. The catalog works similarly, presenting the items in alphabetical order as if they were entries in a dictionary of fashion, each defined by its historical context and illustrated with sample images. Together, the exhibition and catalog present what could be considered a fashion “canon” for contemporary life.

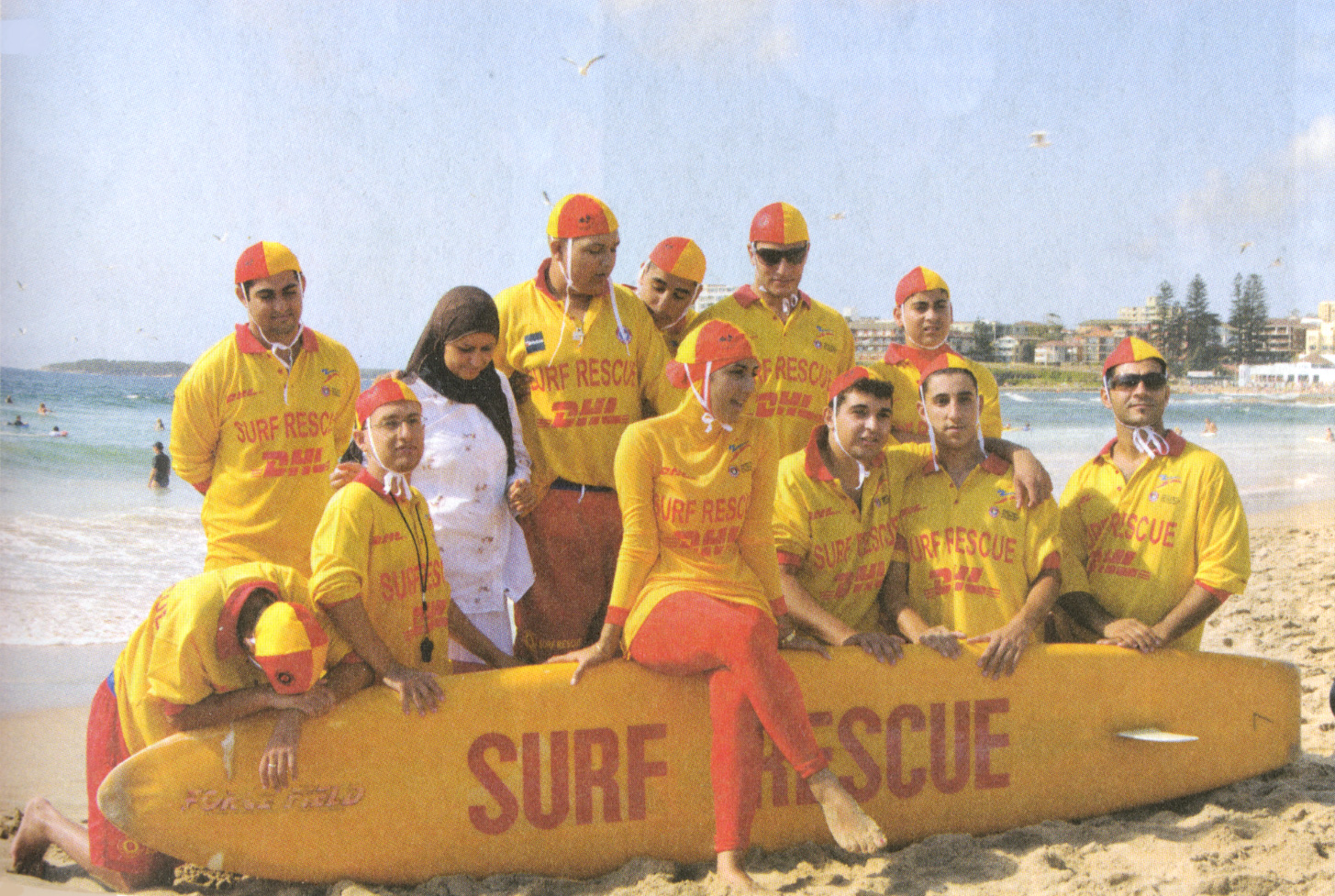

Some of the most fascinating pieces are those created in recent years to meet a practical demand. In one room, displayed next to a string bikini, viewers find a Burkini, conceived in 2003 by Aheda Zanetti, an Australian designer who was born in Lebanon. Zanetti created the ensemble—which pairs leggings and a tunic with a fitted head covering, all made from high-performance polyester—so that her niece could participate in school sports and enjoy the beach while following conservative rules for Islamic dress. In the catalog, Zanetti describes wearing her own design: “It was my first time swimming in public.” The Burkini bridges traditionalism and modernity, allowing the wearer freedom of movement both physically and within social norms.

Other items, like chino trousers, address the present moment by looking back in time. Originally part of 1840s British military attire, chinos or khaki pants became an anti-uniform and a symbol of 1950s American counterculture-turned-mainstream, worn by Jack Kerouac and Katharine Hepburn alike. Years later, chinos returned to their uniform origins when they became a staple of the 1990s male office worker’s wardrobe. Lately, chinos and khakis have come back into style yet again as an ironic or nostalgic nod to the conformity of the office worker. Each time this nondescript trouser comes back into style, it references its last iteration and signals its wearer’s desire to either join in or distinguish himself.

Curator Paola Antonelli writes in the catalog that “Items” first emerged as a list of “garments that changed the world.” Though that might sound like a grand epithet for jeans and Wonderbras, it applies more easily to pieces in the show that have recently gained political significance. Take, for instance, a bright red Champion hoodie from the 1980s that hangs alone on one wall. Originally designed to keep athletes warm between events, the hoodie has had a complex trajectory: associated with black youth, then white fear of black youth, it has recently been reappropriated very deliberately, after the killing of Trayvon Martin, as a symbol of the Black Lives Matter movement. Colin Kaepernick’s San Francisco 49ers jersey is on view nearby.

The creation of symbols happens quickly in modern life. A dark shadow has been cast over the white and pastel polo shirts on view, after neo-Nazis dressed in the same marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, last August. It is not difficult to imagine other items taking on a political, ironic, or nostalgic charge even over the course of the exhibition’s three-month tenure.

Advertisement

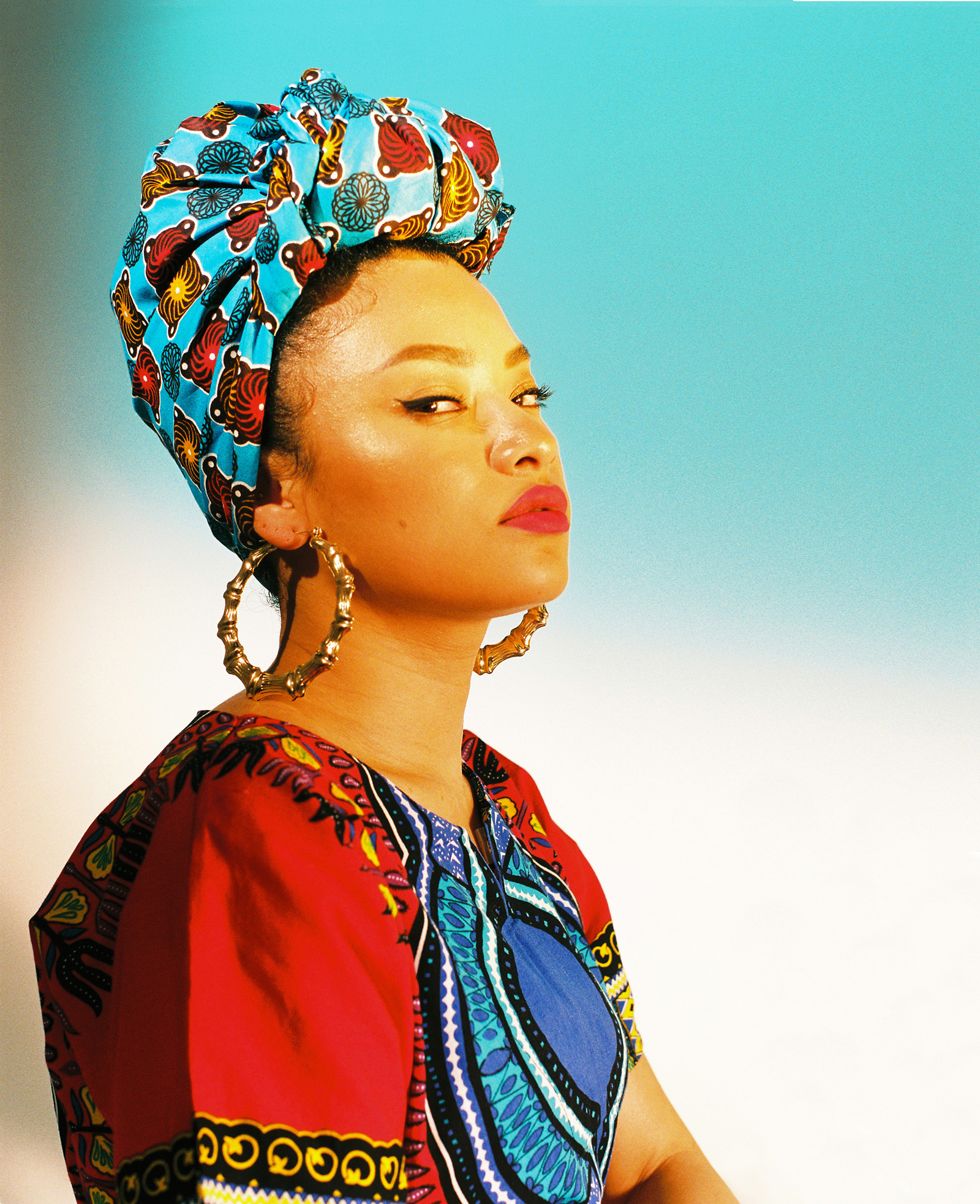

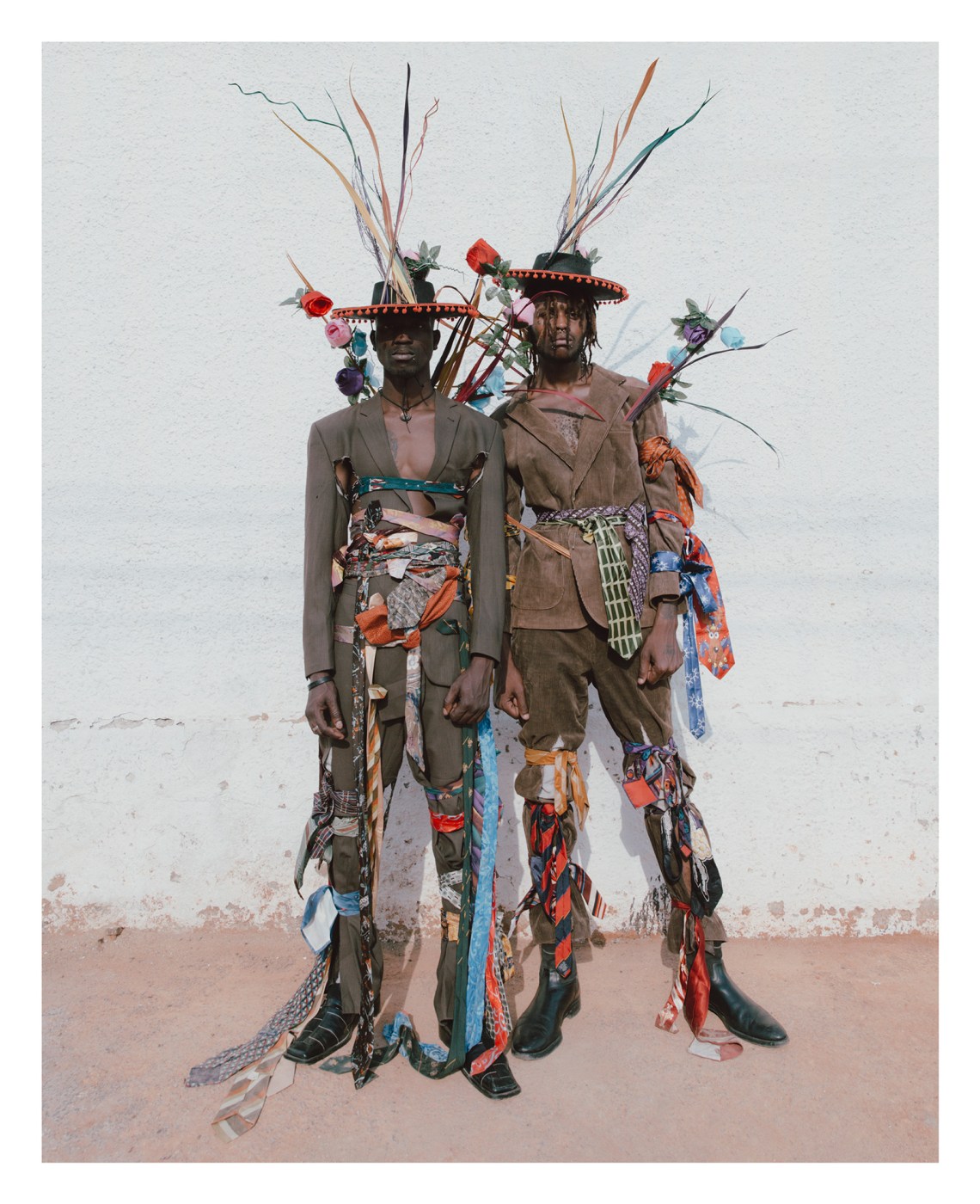

“Items” offers a satisfaction similar to that of a completed list or a well-organized room. It is the catalog, though, that transforms the items from familiar to historically significant. One might even find a hint of Rudofsky’s 1944 “Are Clothes Modern?” conceit in the original fashion photographs included in the “Items” catalog. Shot by five photographers—Omar Victor Diop, Bobby Doherty, Catherine Losing, Monika Mogi, and Kristin-Lee Moolman (in collaboration with Ibrahim Kamara)—these images take the ordinary items featured in the show and place them in settings that are sometimes surreal, sometimes futuristic, and always vibrant and stylish. In a photograph by Catherine Losing, an Hermès Birkin bag sits on a pedestal, evoking a Duchamp readymade. In a photograph by Bobby Doherty, a woman wears a Snugli—a backpack used for carrying children—but in an all-too-modern twist, a King Charles spaniel sits securely in place of a child.

To fully appreciate the pieces in “Items,” it is the viewer’s duty—delight, really—to imagine how she has encountered and used each item over time. That the playful and delightfully bizarre contemporary fashion photographs in the catalog offer a vision of our mundane items beyond what we already know is the show’s most rewarding surprise.

“Items: Is Fashion Modern?” is at the Museum of Modern Art through January 28. The accompanying catalog is published by MoMA.