It’s hard to resist a book where the publisher’s blurb promises “insults in multiple languages” and “sado-masochistic Christmas ornaments.” And Vincent Sardon does not disappoint: here they are, the bondage guys and dolls, trussed up and suspended from luscious green boughs. All done with rubber stamps.

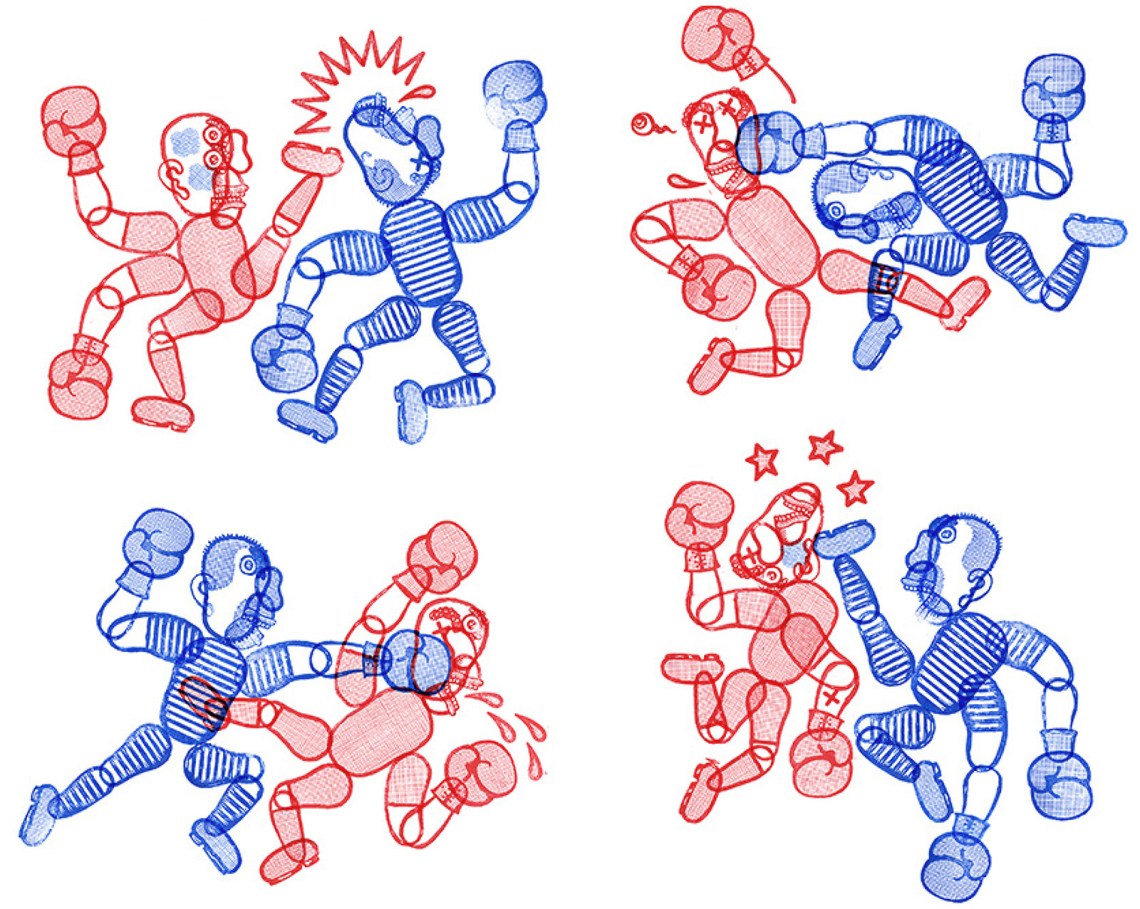

Vincent Sardon: The Stampographer, a new catalogue of his work, is exuberantly bizarre, often foul-mouthed, sometimes boring, sometimes tender. There are jolly naked cowboys, and blue-and-red biff-boff cartoon fights (Republicans and Democrats?), obscene photos and deliberately blasphemous images—not that anyone would disagree with Bernini’s Ecstasy of St Teresa as an illustration for “the orgasm over time.”

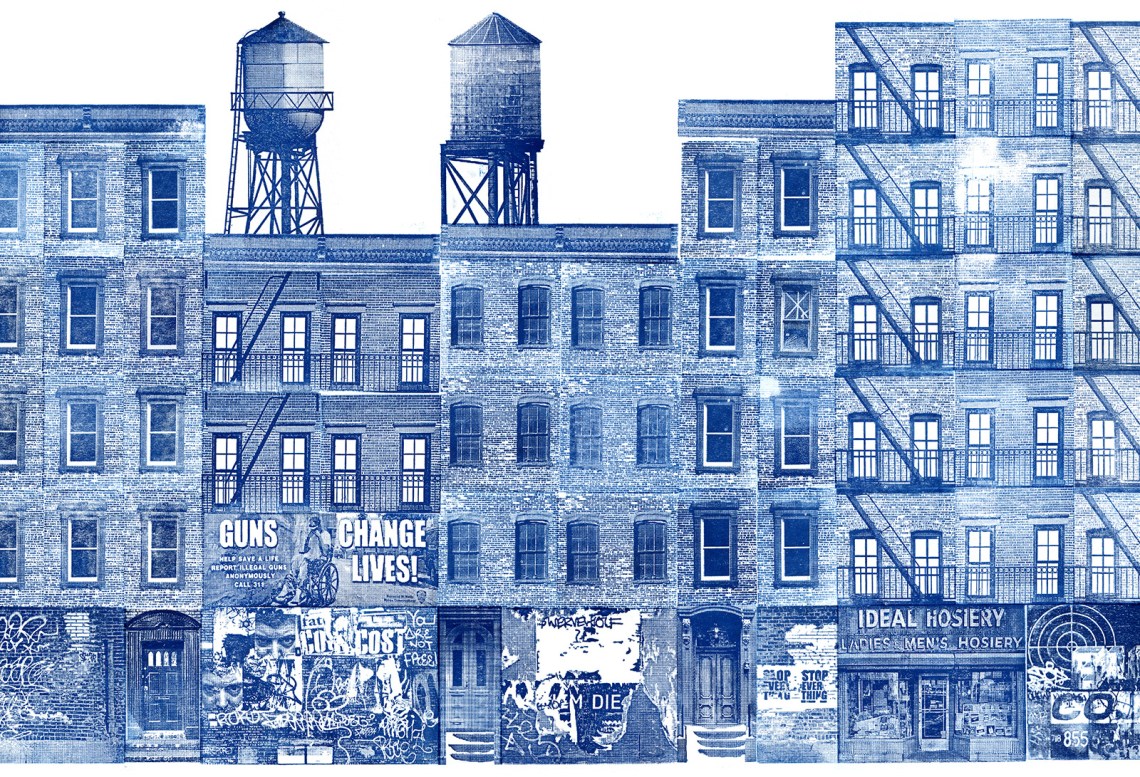

The cluttered, colorful pages are not, however, all sexy romps, wacky violence, and verbal abuse. Many illustrate Sardon’s skill in calmer terms. Two spreads, where the cut side of the blocks faces the reversed, finished print, display the art of building, literally and in stamps. Parisian streets rise, with their shutters and balconies, graffiti and sex shops, and birds fly overhead. We can build our own world, they suggest. And when Sardon cuts blocks for figures, making separate sections for arms, legs, torso, head, we can arrange these, too, to people that world, making a virtual animated cartoon.

Sardon sells his stamps from a shop in the Rue du Repos, near the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris. It opens for odd hours during the week and on Saturdays crowds rummage through the boxes and stare at the stamps on the walls. (This September, the Printed Matter NY Art Book Fair showed an installation, “a little parallel universe to his Paris shop.”) Le Tampographe Sardon is indubitably an art shop, however much its owner shouts that he dislikes artists and couldn’t care less about “the shit they usually produce.” He won’t sell to artists, he insists, but only to amateurs, “the innocent.” Sardon bites things that unsettle him, even, or especially, from his own past. As an art student at the University of Bordeaux, he began engraving in lino, copper, zinc, wood—anything that came his way—and made his first stamps, tampons, gouging them with a chisel from wood or from cheap erasers. But he also wrote and illustrated fanzines and alternative comic strips, and, in the early 1990s, worked on pioneering magazines in the stable of L’Association, the irreverent publishing group that would kick new life into the grand old French tradition of comic books, bandes dessinées. In 1997, Sardon went on to draw cartoons for the left-wing paper Libération, leaving after ten years, disillusioned, feeling in danger of becoming a mere PR rep for the French Socialist Party. Free of the leash, he could concentrate on his stamps.

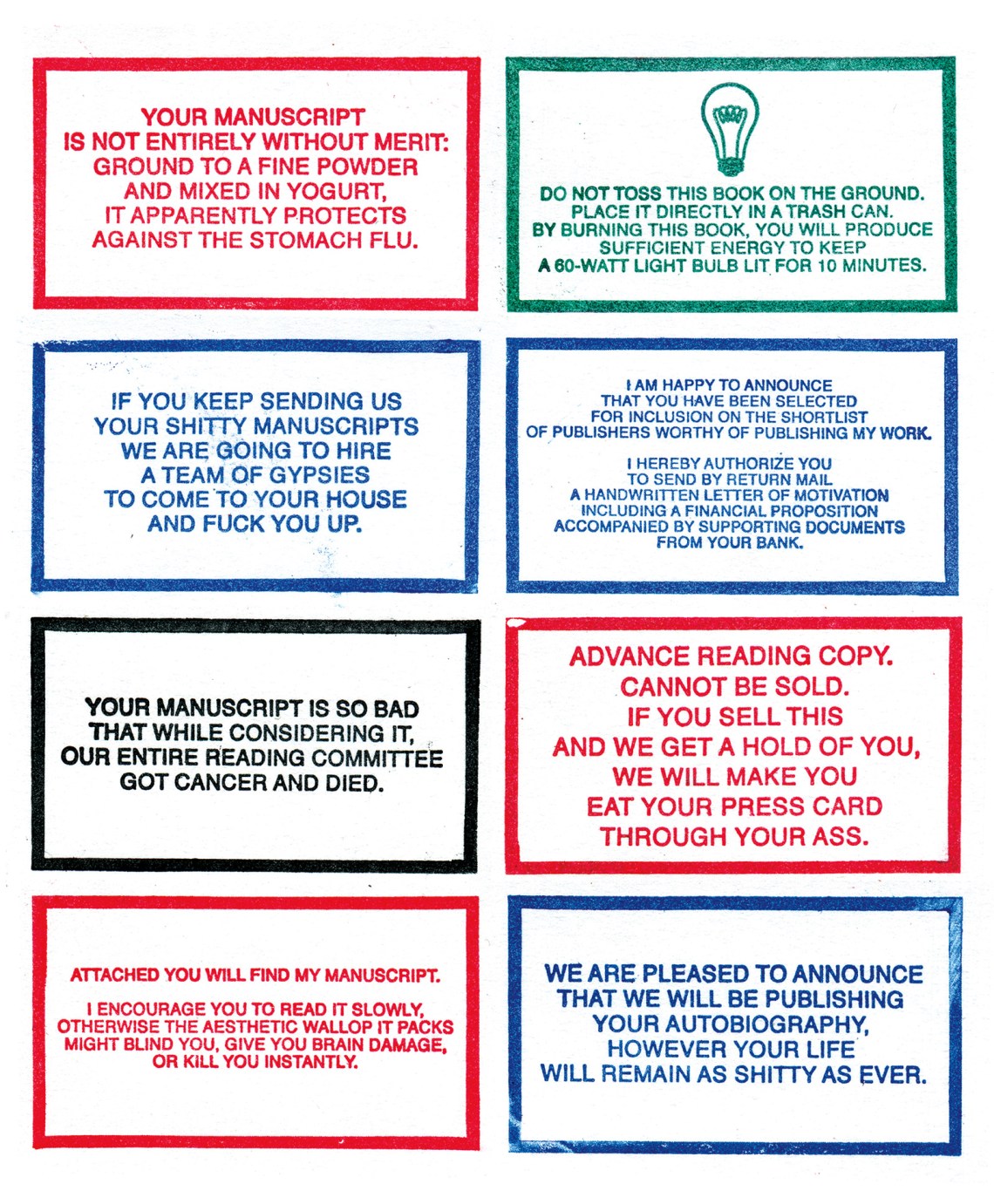

Sardon has become a minor cult figure in France since L’Association published four years of his blog as Le Tampographe in 2012. The blog still runs, a joyous, vivid, grumbling journal with forty-second videos in which designs assemble magically as if of their own accord—one shows the “Black metal” musicians in The Stampographer jumping into life, bats and flames and all. The current book, however, is an English-language catalogue published by Siglio in New York, and the playful brutality—or brutal playfulness—of French humor often doesn’t translate well. Having spent my working life as an editor, I did grin at the publishers’ stamps raging against shitty manuscripts. But the insults pall fast: it’s like living with a boring teenager permanently sticking a “fuck you” finger up to the world. And the wit and charm of a stamped set of wafer biscuits turns sour when every message is a prompt to suicide: “LOSER,” “NOBODY LOVES YOU,” “STOP DREAMING,” “WHY GO ON LIVING?”

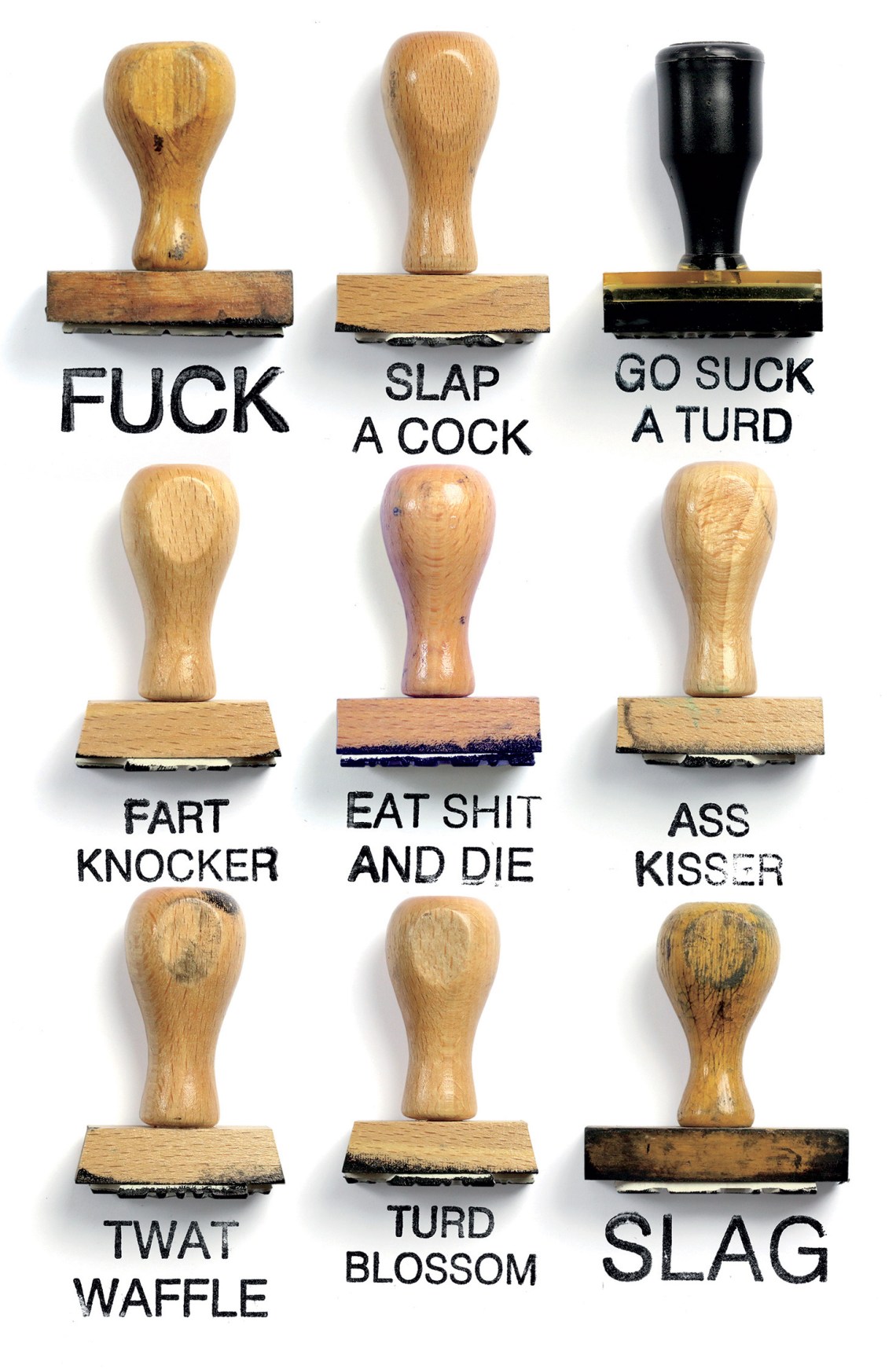

His stamps, Sardon explains, are “miniature portable artistic machines,” at once works of art and tools, and their eclectic images echo Sardon’s sense of inhabiting a disorderly, irrational universe. “My work simply reflects the world,” he says, “which seems to have been created by an absolute moron.” Yet, paradoxically, his careful designs and intricate patterns impose order on that chaos. A stamp is itself is a symbol of order: used on official documents, it conveys authority, it has impact. This, too, to Sardon, is part of its allure. As a student, he says in the interview that concludes this book, he worked in an insurance company, stamping cancellation letters from outraged clients, many of them aggressive, some full of grammatical mistakes that made them seem even more violent. “I won’t deny that I enjoyed reading them,” he says, adding that perhaps this spurred his interest in stamps “and in a certain kind of written violence that stamps convey.” One big stamp read “TO BE DESTROYED.”

Advertisement

The graphic violence stretches back further. Sardon grew up in Bayonne, in Basque country, the grandchild of immigrants from northern Spain who had fought for the anarchists against Franco and fled over the Pyrenees, only to end up in an internment camp and find that refugees were welcomed by the French press as “communist vermin, both arrogant and impossible to assimilate.” Which is, Sardon notes, “rather interesting in light of current French attitudes towards welcoming refugees from the Middle East.” In his childhood in the 1970s, the refugees in Bayonne were Spanish Basque activists: demonstrations were constant, streets smelled of tear gas, and walls were covered with nationalistic slogans and stencils. The 1980s saw Spanish death squads gunning down dissidents. This left Sardon wary of any nation state, French, Basque, or Spanish. He feels French only by chance: “I feel at home nowhere, and see this as a privilege and a form of freedom.”

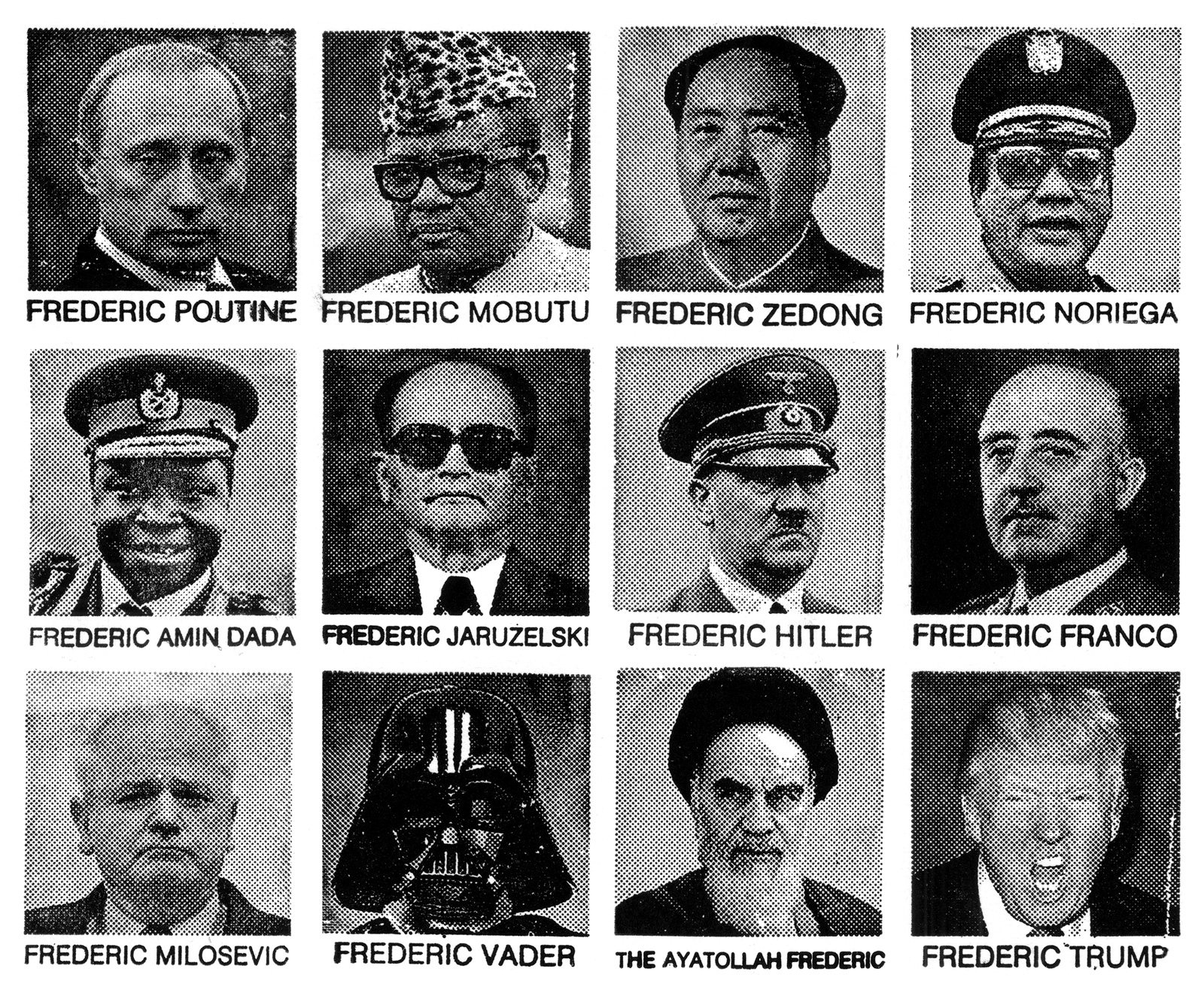

Dictators make good copy for his stamps—I particularly liked the page of “Frederics,” which includes Frederic Stalin, and Frederic Franco, as well as The Ayatollah Frederic and Frederic Trump. Deadly militarism streams off inked rollers: soldiers, tanks, planes. And nationalism is still a target: one sequence combines sex manual and politics, with the “little galilelean choo-choo train” morphing into “the palestinian tourniquet” and “Jerusalem’s little backdoor.” Who is screwing whom?

Sardon’s work has been called anarchistic and his humor Dadaist, but those terms don’t feel quite right. Like a Nonsense poet, he pounces on the random and vulgar and threatening, and uses them to create order, and deliver messages of a disconcerting kind. His craft shares the technical virtuosity and moral waywardness of Nonsense: it’s no surprise to find that as a boy he fell under the spell of the novelist and songwriter Boris Vian, and then of Alfred Jarry and Ubu Roi. Later he joined the Jarry-inspired Collège de ’Pataphysique (a term that deliberately defies explanation, except as the science of imaginary solutions), feeling “that in them I had found a group of people capable of appreciating the utter uselessness of my work.”

I can’t help feeling that he protests too much. There’s a niggling sense that Sardon wants to be considered useless, and worse—mad, bad, and dangerous to know. Despite the acclaim, he wants to remain an outsider artist. He likes the idea of being offensive, shocking people, having “enemies.” But in many ways, as he shows in the published interview and on his blog, he’s curiously conventional and nostalgic, ranting against Facebook and social media, and against gentrification and the flow of artists and television companies into the old streets of his arrondissement. He’s far from cool: like other parodists, his satires of artists—Dubuffy, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Pollock, or the idiosyncratic autodidact Gaston Chaissac—are tributes to the power he sees in them.

Children love bashing rubber stamps on paper or making potato cuts, and a willful childishness is part of The Stampographer’s appeal. But some designs are miraculously adult and delicate, notably the floating dragonflies who hover over the final page. There is passion here, and power, and a lyrical delight in color and form, as well as technical skill. Stampography is a ludic art, a game, a play of poetry. Whether he likes it or not, Vincent Sardon is an artist—and his stamps do make you laugh.

Vincent Sardon: The Stampographer will be published by Siglio on November 21.