Her name is Henda Ayari. She is forty years old and a Muslim; she was a Salafist, meaning that she adhered to a pietistic form of Islam. She says she’s still a Muslim, but she has abandoned the headscarf she wore for a long time. In 2016, she became a cause célèbre when she published a memoir, J’ai choisi d’être libre (I Chose to Be Free), in which she described her experience of brutalization at the hands of a violent husband. She also alleged that she was sexually assaulted by a Muslim preacher, whom she called Zoubeyr.

In October 2017, she became a cause célèbre all over again—this time in the wake of the Weinstein Affair, the ever-widening wave of revelations about sexual harassment and sexual assaults carried out by famous and powerful men. In France, the #MeToo hashtag was rendered as #BalanceTonPorc, which translates as “Squeal on your pig.” Ayari now revealed the real identity of Zoubeyr. His name is Tariq Ramadan. About a week later, another woman, who has remained anonymous, also made a complaint against him. Her testimony is terrifying: Ramadan is said to have “raped, assaulted, and humiliated” her. Soon afterward, four women in Geneva also accused him of forced sexual relations between 1984 and 2004, when they were between fourteen and eighteen years old. All the women described a relationship of subordination imposed by an authoritarian figure who needed to have women under his control. Ramadan has denied the allegations, blaming “a campaign of slander” orchestrated by his enemies and issuing a libel action in Paris.

Such is the “Ramadan Affair” that has scandalized and enraged France, but this was hardly the first time the Islamic scholar had been the center of controversy. The accusations of sexual assault and abuse have only added a vicious new energy to an already bitter debate concerning Ramadan that has divided French society.

So who is Tariq Ramadan? Born in Geneva, and resident in Switzerland, he is a grandson of Hassan al-Banna, the Egyptian founder of the Muslim Brotherhood. A controversial expert on Islam, Ramadan has taught in prestigious universities and was a professor at Oxford until he was placed on leave after the sexual assault scandal blew up. Long before that, Ramadan had earned notoriety for his writings and his activities. For thirty years, he was one of the foremost spokesmen for Islam on the European media scene. In France, his books, articles, and lectures have generated a blend of polemic, praise, and poison such as only true gurus can arouse.

For those in France who despise Ramadan, he has always practiced “doublespeak,” using his rhetorical talents to mask a covert but consistent message of jihad against the West—in particular, the critics say, against democracy and women’s rights. Among these opponents are many French intellectuals—such as the philosopher Elisabeth Badinter—as well as politicians of both right and left, notably the former Socialist prime minister Manuel Valls. For Ramadan’s defenders—whether they are Muslim or not, and whether they agree with him or not—Ramadan represents and articulates a path for Islam to engage with modernity without denying its foundations. These defenders, who include the renowned scholars of Islam Olivier Roy and François Burgat, reject the “doublespeak” idea. Burgat has observed that there is not a single French Muslim who has gone to Syria for jihad who has cited Tariq Ramadan as an influence. Indeed, many jihadists denounce Ramadan as a Western stooge.

For most of his career, Ramadan has generally enjoyed a favorable reception in English-speaking countries. After the terrorist attacks in London in 2005, he was invited by Prime Minister Tony Blair to take part as an adviser in a working group on Islamist extremism. In France, though, Ramadan has been embroiled in controversy. To his message to Muslims that they can be fully true to their faith and fully Western at the same time, and that sharia, or Islamic law, is not a divine essence but can be adapted to modernity, his adversaries respond that he is equivocating and scheming. They say that his goal is to disrupt the equilibrium of a country where there is a long-settled separation of church and state.

In 2004, Ramadan caused a storm when he initially called on Muslims in France to oppose the law against religious symbols in public schools, which de facto banned the wearing of the headscarf. Then, in 2005, Ramadan appealed for a “moratorium on corporal punishment, stoning, and the death penalty” in Muslim countries. The journalist Caroline Fourest jumped on this: because Ramadan was calling for a moratorium only on the lapidation of women, and not a ban, this was proof that he was not opposed to it in principle; that proved he was a fundamentalist in disguise. Ramadan responded that “it is not enough to condemn to advance things,” and that for Muslim countries to evolve, you have to “open the debate and find a pedagogy.” Ramadan has also been accused of homophobia and anti-Semitism. When in February 2016, he declared before an assembly of Muslims that “France is now a Muslim culture,” many claimed that the mask had slipped: this showed that Ramadan wanted to impose sharia in France as a legal norm.

Advertisement

The arguably artificial controversies aside, there are several reasons why Ramadan has become such a divisive figure in France. France’s Muslim population is larger (at about 8 percent of the total) than its counterparts in other European nations like Germany and Britain (both around 6 percent), and France has a “guilty conscience” about its Muslims thanks to its colonial history of subjugating Arab populations and Algeria’s bloody war of independence (1954–1962), which France ultimately lost. Ramadan was, for a time, an important example for Muslim communities in France, particularly among their youth, because he incarnated success and fame, but he was also an effective advocate for the legitimacy of Islam as a religious practice, which had until then been confined to the margins of society. To young Muslims of the quartiers, those underprivileged neighborhoods on the outskirts of major cities, Ramadan restored a sense of pride in being Muslim.

Finally, it is impossible to make sense of the Ramadan Affair without an account of what secularism, or laïcité, means in France. The principles of laïcité were foundational to the republic, and their influence was consolidated in the second half of the nineteenth century. French laïcité, which is distinct from Anglo-Saxon secularism, rests on three pillars: the separation of church and state, freedom and equality for all forms of worship, and the neutrality of the state in matters of religion. It would be unimaginable in France to have a banknote proclaiming In God We Trust. Why God? And which God exactly?

These principles were fought for and won in a France once known as the “eldest daughter of the church,” in which the Catholic Church was traditionally pro-monarchic and played a huge political part. Their eventual inscription in France’s constitution was a historic victory for the republican forces in French politics, largely of the left. From the start, though, the fight for laïcité was marked by a split between two camps. One was radically anticlerical; Victor Hugo was its great figurehead. This camp directly opposed the Catholic clericalism that rose to prominence in the nineteenth century. From the early twentieth century, under the slogan “Down with the red skullcaps,” referring to cardinals’ caps, this group gathered a coalition that ran from the Radical Party, representing a provincial bourgeoisie of the moderate left, all the way to anarchists. It tried to confine religion to the private sphere, restricted to its places of worship.

The second camp, led by mainstream socialists like Aristide Briand and Jean Jaurès, preferred a doctrine of state neutrality and the protection of the rights of minority religions, which in France then meant Protestantism and Judaism, rather than an outright ban on displays of religiosity in the public sphere. It is this second tendency that won during the debate in 1905 when it came to a vote on the law on the separation of church and state. In his 2014 book La république, l’islam et le monde, Alain Gresh recalls that “the Council of State, which had to interpret the 1905 law, did so in a liberal sense, assuring the right of churches to organize themselves as they wish, including in the public space.” Between 1906 and 1930, many municipal mayors in France tried to ban public processions by Catholics. In 136 cases out of 139, their rulings were overturned by the courts. Nevertheless, a virulent anticlericalism remained a potent force in French society.

A hundred years later, it was in the name of a “pure and tough” laïcité that the National Front started a campaign in France to marginalize the Muslim religion. It is no small paradox to see the heir of an extreme-right and vigorously antisecular tradition in France today proclaim laïcité as an article of faith and demand its strictest possible application to Islam. Over the past three decades in France, the hard right has forced a debate on “French identity” that aims to show Islam is incompatible with France and the Republic in all circumstances. In its wake, many so-called “identitarian” groupings have emerged in French society. One of the most important is Riposte Laïque, which was founded in 2007 and whose website these days promotes a book titled Pourquoi et comment interdire l’islam (Why and How to Ban Islam).

This vein of nativist, nationalist identity politics has spread within, and beyond, the traditional conservative camp. After President Nicolas Sarkozy was elected in 2007, he created a Ministry of Immigration, Integration, National Identity, and Cooperative Development. When a Socialist government came to power in 2012, it followed Sarkozy’s lead; its new prime minister, Manuel Valls, became the champion of an intransigent laïcité that saw itself as a bulwark against the threat supposedly posed by Islam to French society. In 2016, Valls supported a ban on the burkini on beaches, while his ally the philosopher Elisabeth Badinter called for a boycott of brands that sold so-called Islamic fashion.

Advertisement

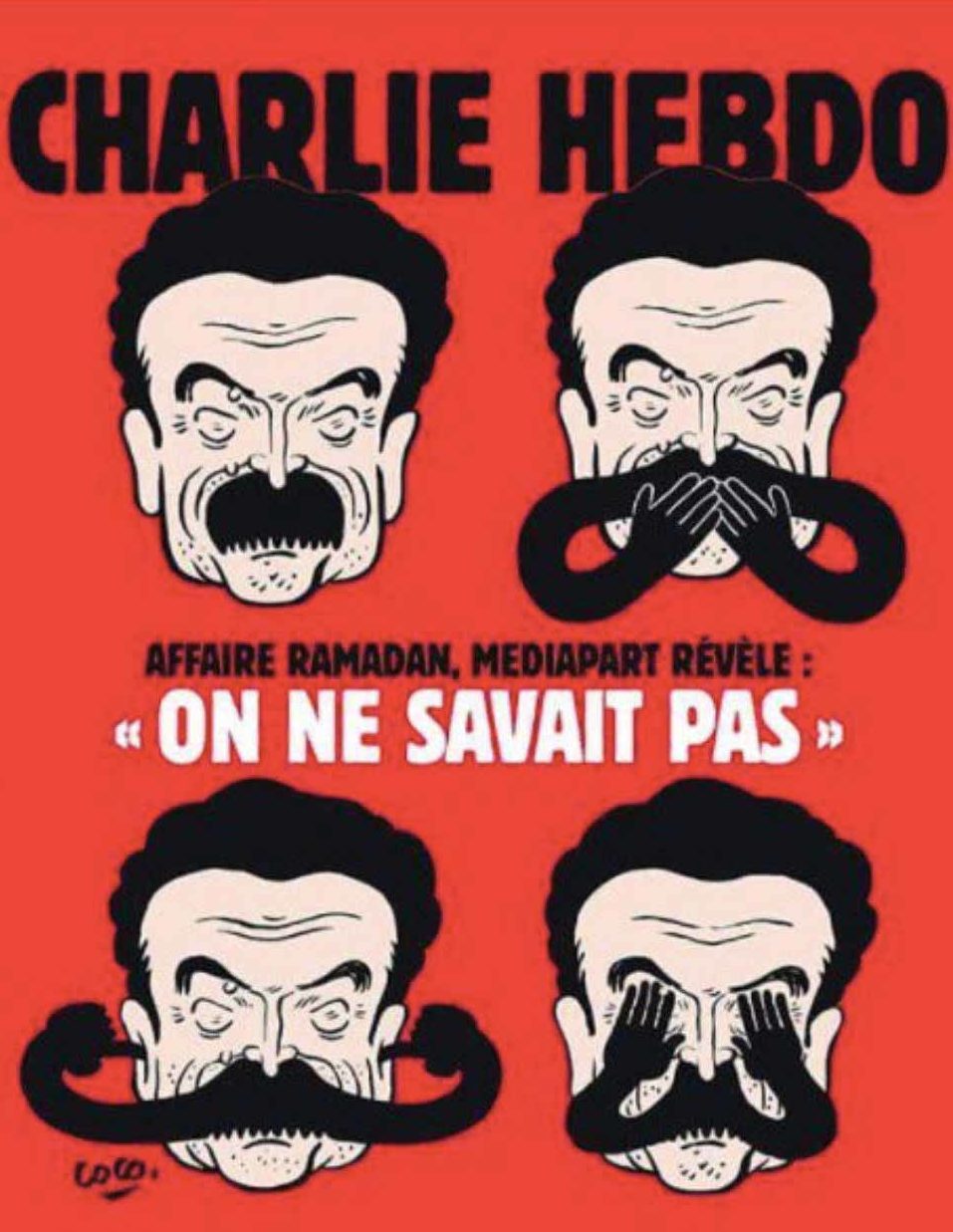

This was the background when, about ten days after Henda Ayari filed her complaint accusing Ramadan of rape, the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo—which had been attacked by two armed jihadists in 2015, who murdered twelve people, including eight of the paper’s editorial team—published a cartoon showing Edwy Plenel, the editor of Mediapart, a left-wing online news outlet, with a mustache so bushy that it covered his eyes, ears, and nose, accompanied by the caption: “On the Ramadan Affair, Mediapart reveals ‘We did not know.’” What didn’t Mediapart know? It could hardly concern the alleged sexual misconduct of the Islamic scholar, since no one—not even Ramadan’s fiercest detractors—had published such accusations against him before Ayari issued her complaint (which Mediapart itself reported). What Charlie Hebdo’s editors meant is that Mediapart had previously closed its eyes and ears to the menace of Ramadan’s monstrous ideas—which, the cartoon implied, were somehow of a piece with his sexual misconduct.

Mediapart represents, among other things, an evolving current in French society of multiculturalism, including the defense of immigrants and minorities. In 2015, Plenel published a book titled Pour les musulmans. The title echoed a famous article by Emile Zola, “Pour les juifs,” published in 1896 in defense of Captain Dreyfus. Plenel’s book made an explicit analogy between the wave of Islamophobia now plaguing France and the anti-Semitism that existed during the Dreyfus Affair. The “blindness” supposedly demonstrated by Mediapart and Plenel, according to the accusation of the Charlie Hebdo cartoon, alludes to their agreeing in the past to debate with the Islamic scholar, thus lending legitimacy to his discourse and paving the way for the advance of radical Islamism in France.

Was there any basis for this attack? Hardly. In 2016, Mediapart published a five-part investigative series on Ramadan, his networks, his hold over some young Muslims, his ambiguous statements, his former financial links with the Gulf state of Qatar, and so on. In the past, Mediapart has also given major coverage to sexual harassment and violence toward women. Yet that counted for little. The supporters of Charlie are mobilized. When Plenel declared on the radio station franceinfo that “a left that no longer knows where it is, has allied with a right, or even an extreme identitarian right, to find any pretext, any calumny, to return to the obsession with the war on Muslims and the demonization of everything concerning Islam and Muslims,” the editor-in-chief of the satirical magazine, Laurent Sourisseau, known as Riss, retorted that, by accusing Charlie of making “war on Islam,” Plenel was “condemning it to death a second time” and excusing in advance any future Islamist killers. In short, the attack on Mediapart and Plenel had nothing to do with sexual harassment or the abuse of male power. Rather, Charlie Hebdo’s editors chose to use Ramadan’s presumed sexual misconduct to scapegoat a movement that wants to see France evolve in the direction of multiculturalism (or what, in the United States, might be called diversity). “The debate is a trap, jinxed, impossible,” one Mediapart journalist commented despairingly. “What can one say to people who have taken gunfire?”

On Mediapart’s side, however, came a petition signed by some 160 notables, including the economist Thomas Piketty, the screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, the filmmaker Costa-Gavras, and the sociologists Edgar Morin and Alain Joxe. They declared:

We seem to be confronted by a political campaign that—far from defending the cause of women—manipulates it to impose on our country a deleterious agenda composed of hate and fear. This campaign attacks the newspaper that for almost ten years has constantly fought this politics of fear, defending the cause of equality against all kinds of discrimination, whether aimed at women, LGBTs, Muslims, blacks, Jews, victims of racism and xenophobia, migrants, and refugees.

The debate is beset by irrationality and landmines. To take just one example: yes, part of the far left tends to overlook the virulent anti-Semitism that exists in certain Muslim circles—which is visible now in the online forums full of messages calling Ramadan’s principal accuser, Henda Ayari, a “Zionist whore” and worse. But the counter-attack against “Islamo-leftism” represents any advocates of Muslims’ benign integration into France as being, at best, the “useful idiots” of jihadism, complicit in an ideology that nourishes racism.

The latest jibes against Mediapart, led by Manuel Valls, have taken a disturbing turn. The former Socialist prime minister has cultivated an image of being the left’s standard-bearer in a struggle against radical Islamism that, in the name of pure laïcité, is virtually a struggle against Islam, period. Valls has defined the terms of his politics thus: “Of course, there is the economy and unemployment. But essentially, it is a cultural and identity battle.” Embracing the part of demagogue, he recently said of Mediapart and Plenel: “I want them to choke, I want them removed from the public debate.” Plenel responded by denouncing Valls’s “political drift toward authoritarian and intolerant shores”—though such attacks against Mediapart were “only a symptom of a country that is not always clear either about its democratic culture or about its plural identity. The symptom, too, of an uncertain era that tiptoes between democratic impatience and authoritarian temptations.”

The Ramadan Affair has thus reopened the historical split over laïcité within the French left, but the dispute has found new grounds—about whether national identity is something fixed or evolving, about what place Muslims and immigrants have in the country’s future. These cleavages, which divide not only the French left but society in general, are something Emmanuel Macron had hoped to elude. Macron did succeed in excluding from the 2017 election presidential campaign an identitarian politics that for three decades has sought to supply a resounding “Non!” to the question: Is Islam compatible with the French republic? In his campaign book, Revolution, Macron tried to circumvent the issue with a message of tolerance. “Laïcité is a freedom before it is an interdiction. It is made for each person to be integrated,” he wrote. “How can one ask our fellow citizens to believe in the Republic if some of them use laïcité to tell them they don’t have a place in it?”

On one rare occasion during his election campaign, Macron directly criticized those who apply a “vengeful laïcité”—and when he did so, he placed himself at the opposite pole to Valls. But today, in the wake of the Ramadan Affair, Macron finds himself caught up in the return of this controversy over Islam and French identity. This time, it is neither the far right of Marine Le Pen’s National Front, nor those of the Gaullist right who emulate Sarkozy, who are winning, but an ex-Socialist who still claims to be on the left (he quit the party after the election). Valls may lack a political home for now, but he has signaled that he means to make identity—Islam vs. France—his main theme. If President Macron fails to pull the country out of its socio-economic doldrums, he will have to face a dangerously sharpened identity politics.

—translated by Susan Emanuel