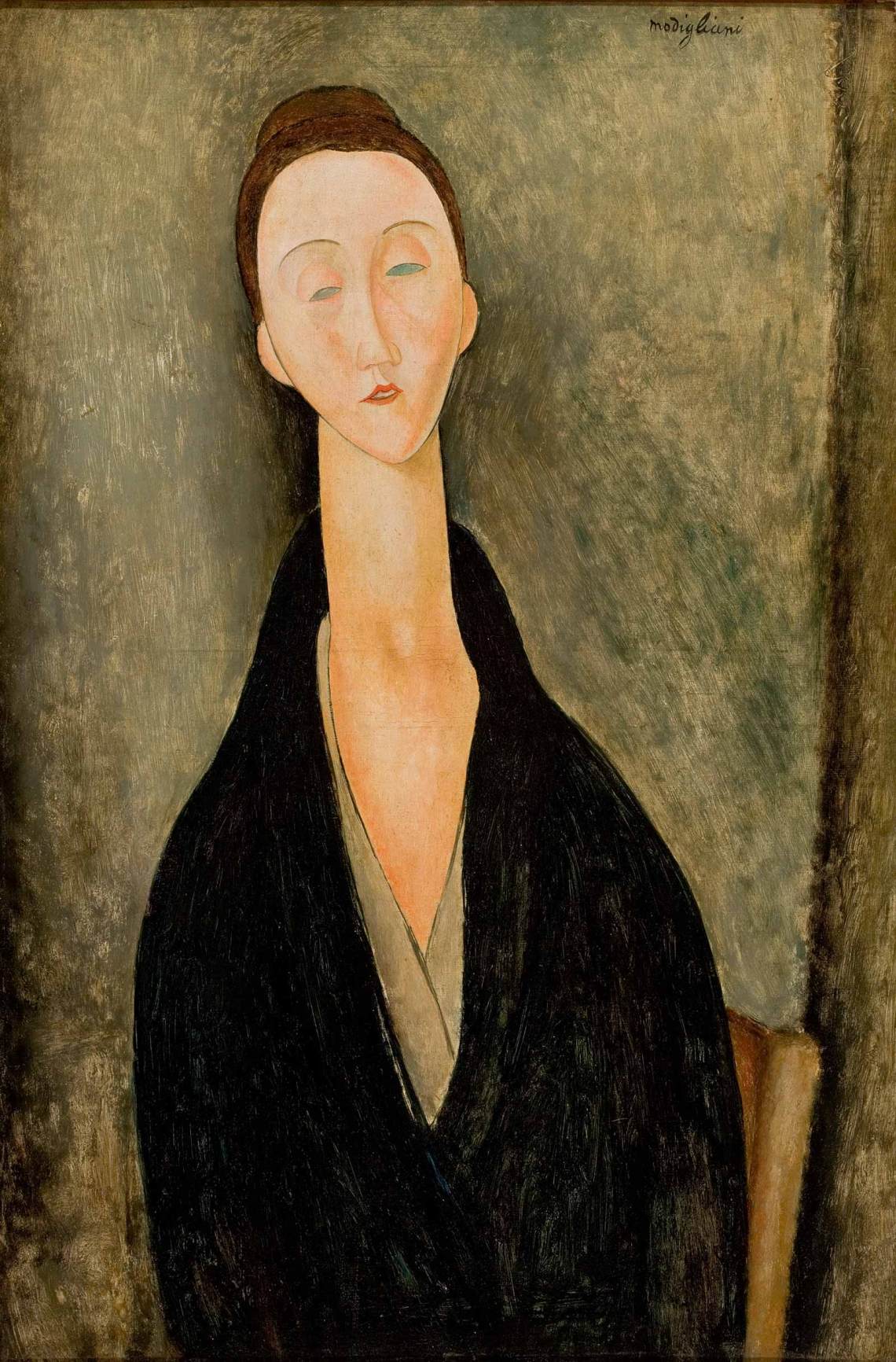

A single Modigliani portrait or nude is strikingly beautiful—the elongated face, the tilted head, the lithe pose. Yet when a host of them crowds together, as they do in a major retrospective currently at the Tate Modern, the initial impact is oddly diluted. Surrounded by portraits from his first years in Paris, my first response was, “Surely they couldn’t all have had V-shaped eyebrows and sunken, oval eyes?” The mannerisms display a young man out to make a mark, to signal his presence in an immediately recognizable style. It’s irresistible to quote Jean Cocteau, who left Amedeo Modigliani’s portrait of him in the studio because, he claimed, he couldn’t afford the cab-fare to take it home. “It doesn’t look like me,” he said. “But it does look like Modigliani, which is better.”

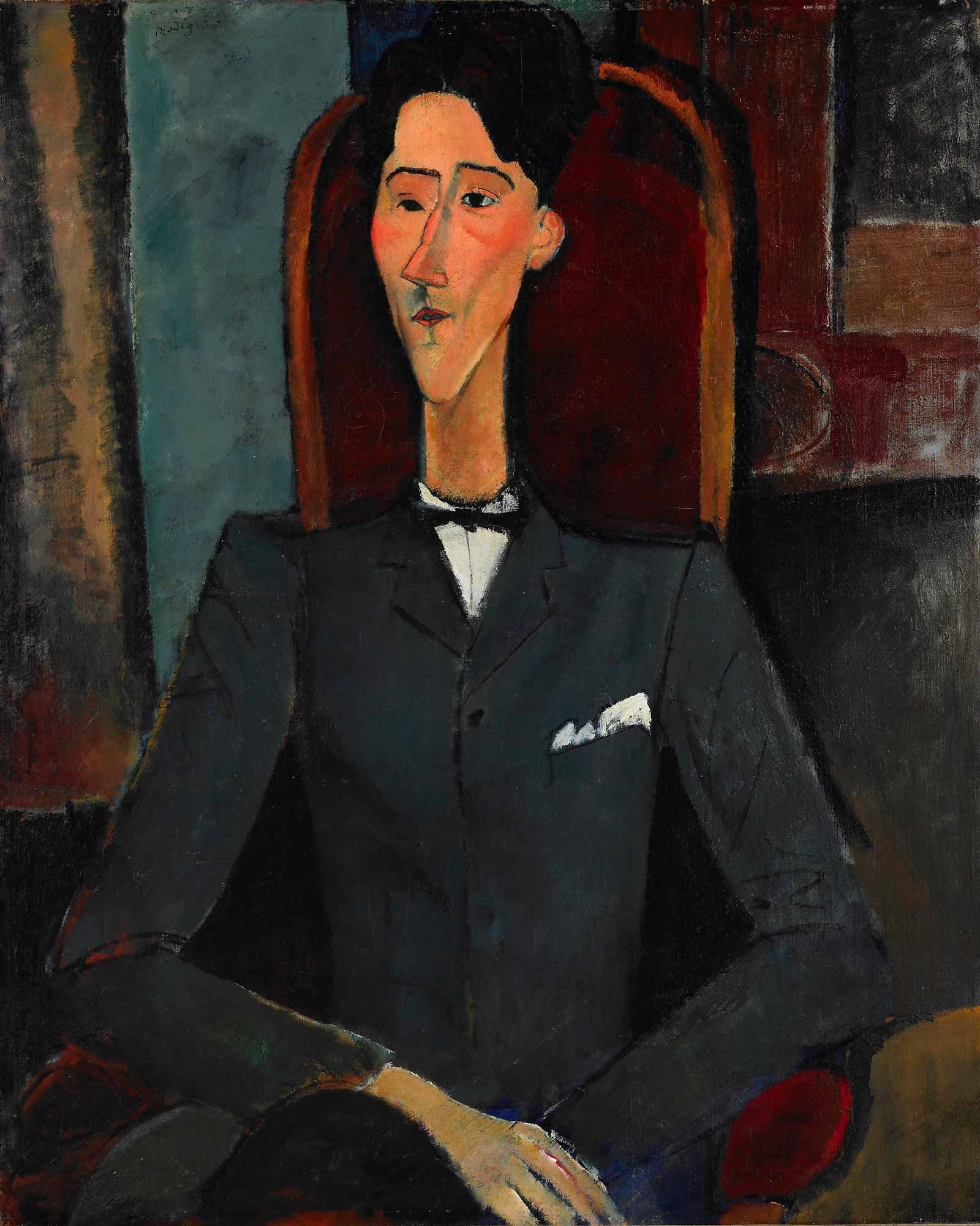

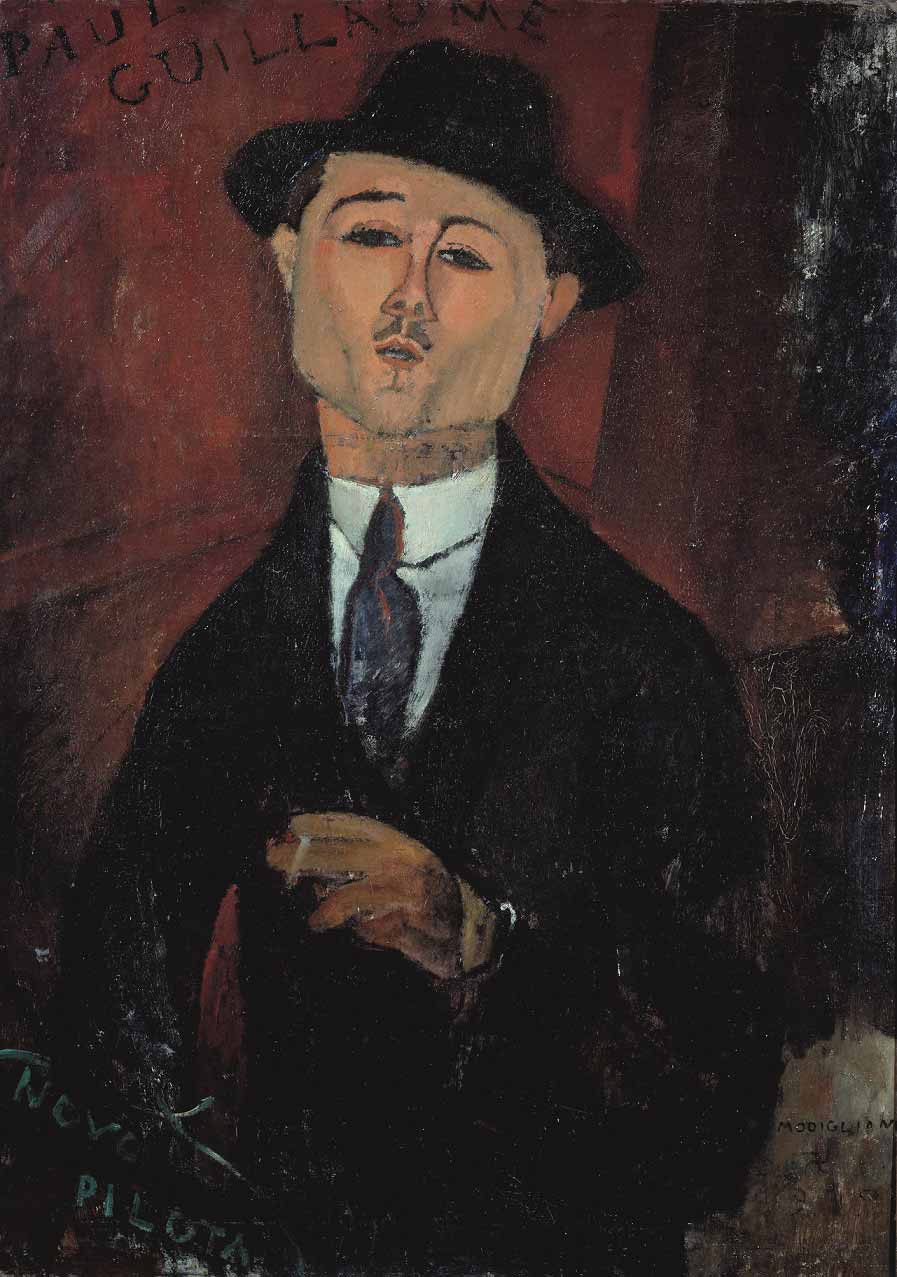

To emphasize the sameness of the portraits, though, is to ignore the subtle modulations, the rough backgrounds that let the figure stand out, the urgent quest for expression, perhaps a striving to understand the nature of identity itself. Sometimes, Modigliani suggests the spirit of his subjects so acutely that we can almost hear them talking, as in the portraits of his dapper, nervy patron, Paul Guillaume. And in the Tate show, two people escape his formula altogether, as if their personalities were too large to fit the frame. One is an unrecognizable, bubble-faced Picasso, the other a marvelously forceful Diego Rivera, filling the canvas with rolling energy.

A Sephardic Jew, born into a trading family in Livorno, Modigliani was often ill, suffering from tuberculosis in childhood. In his teens, he studied art and paid visits to Venice, Florence, and Siena, and read Baudelaire and Mallarmé, Nietzsche, and Bergson. Restless and bored, he dreamed of Paris, home of the daring Cubists and Fauves. He arrived there in 1906, aged twenty-one, two years after Picasso, Matisse, and Brancusi, and headed straight for the legendary bohemian village Montmartre. There, he found a patron in the doctor and collector Paul Alexandre, and shared studio space with other artists in the rue du Delta. (A fine portrait of Paul’s brother, Jean Alexandre, with a sweet-faced nude on the back of the canvas, is like an image of the dress and undress of this milieu.)

An evocative montage of photographs and film brings Montmartre before us and shows Modigliani on the move in 1909, when he followed Brancusi across the city to Montparnasse. With its famous cafés of La Rotonde, Le Dome, and La Closerie des Lilas, and the collective studios of La Ruche (the beehive), Montparnasse was a crossroads of ideas and aesthetic movements, consciously cosmopolitan. Modigliani’s early works, with their rough brushwork and bright colors, show how he had studied Cézanne and Toulouse-Lautrec, while his pale-visaged women betray their Symbolist heritage.

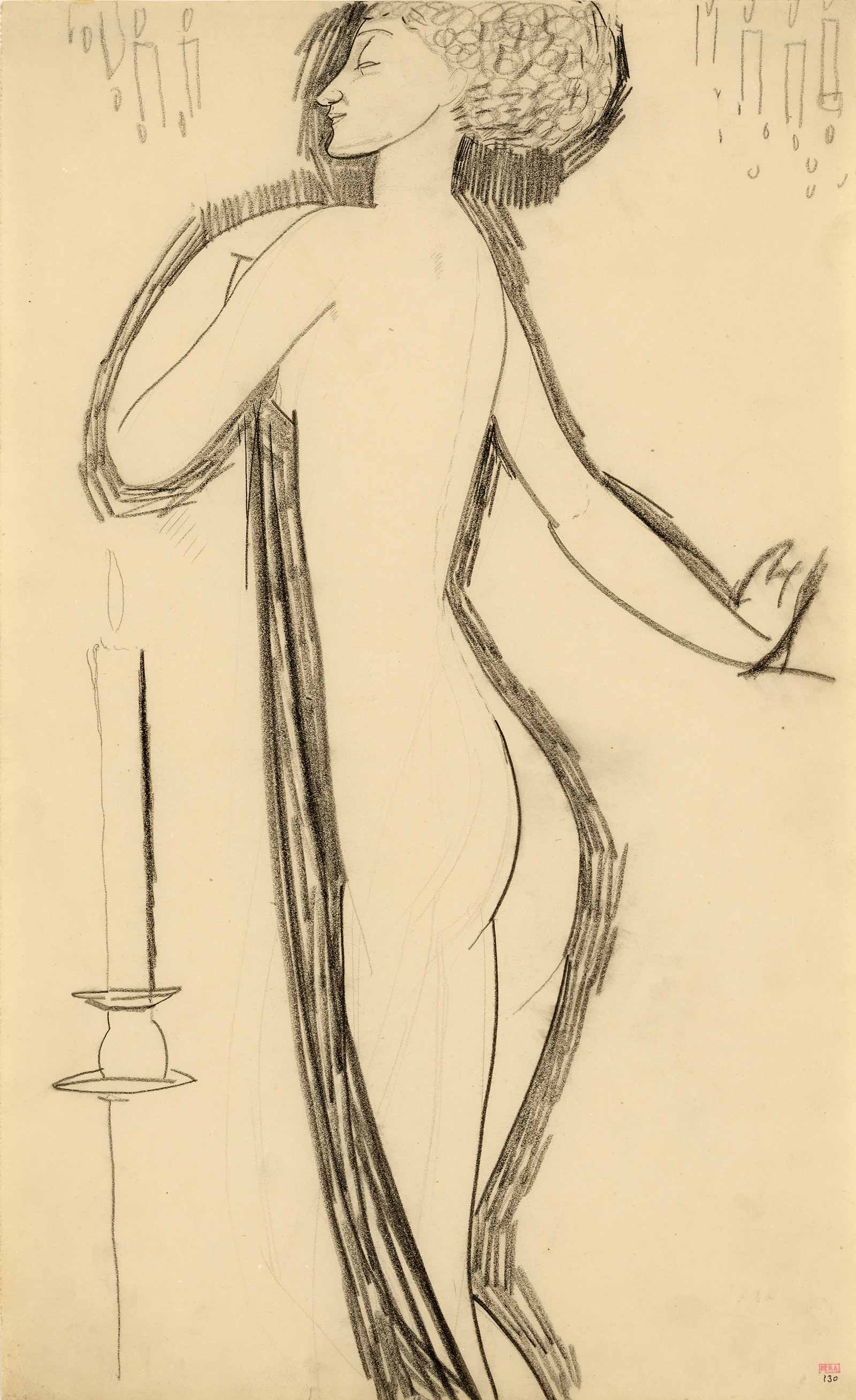

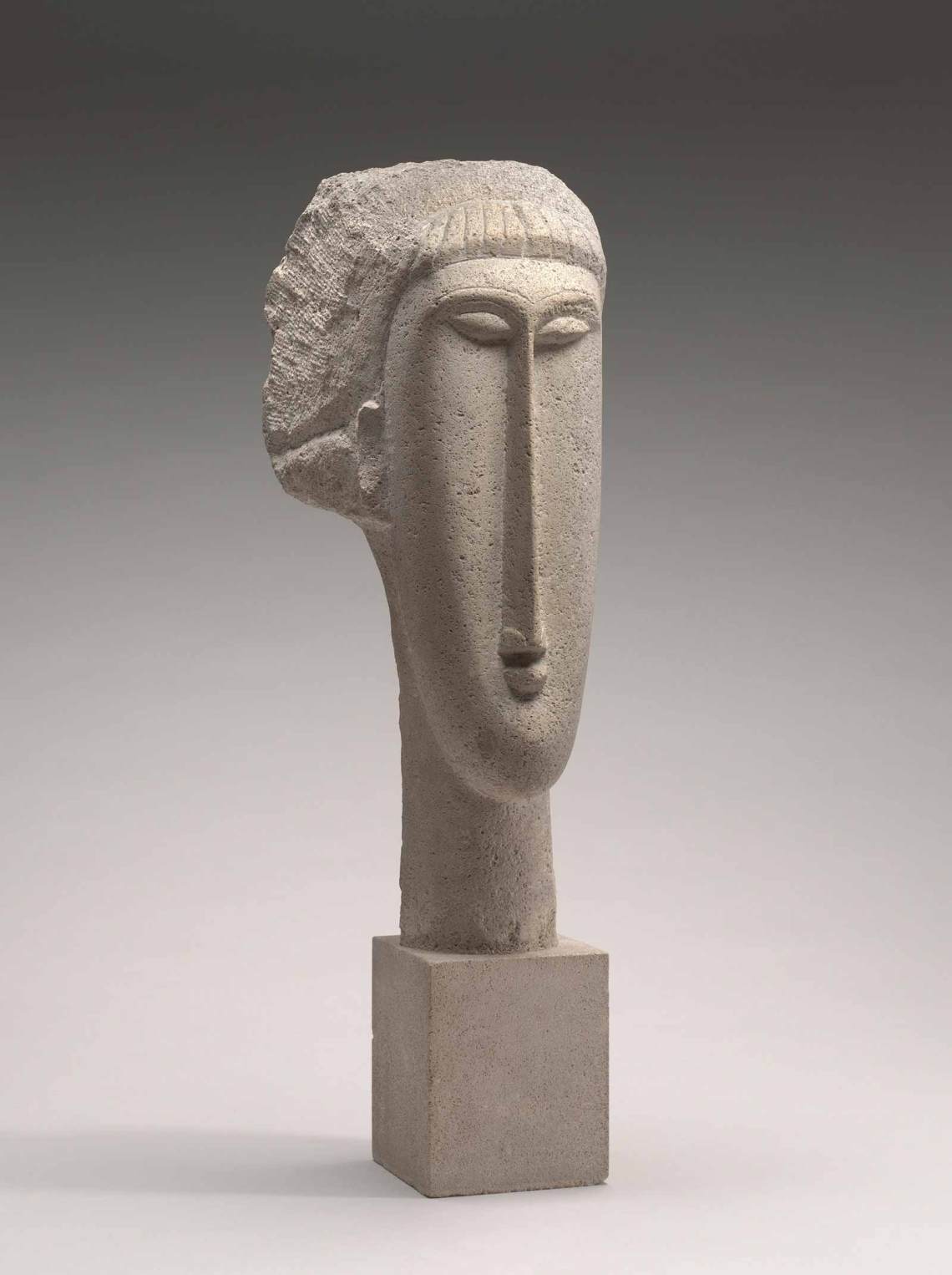

Soon, though, like many of his peers, Modigliani looked further afield, becoming fascinated by primitivism, African masks, Egyptian statues, and the “Khmer” Buddhas of Cambodia. Encouraged by Brancusi, he turned back to an early love, sculpture, carving directly from the limestone and sandstone blocks that lay scattered around Paris building sites. Seven of his stone heads, with their elongated, simplified form, appeared among the Cubist paintings at the Salon d’Automne in 1912. The selection of sculpted heads at the Tate—monumental, graceful, eerily calm—are balanced by his drawings of caryatids, exploring the poetics of strength, the body as architecture, or, as he put it “columns of tenderness.”

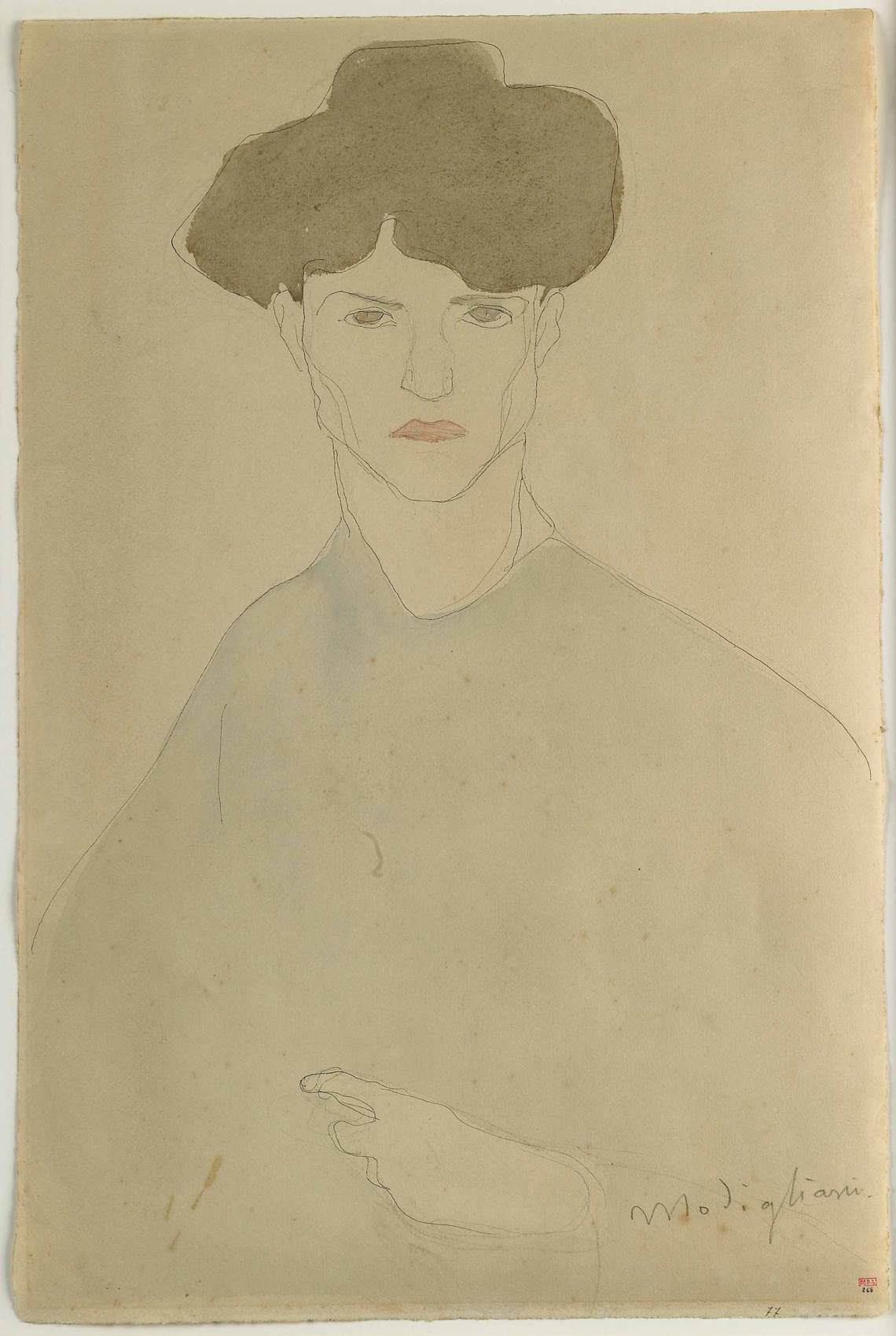

In the concurrent exhibition “Modigliani Unmasked,” at the Jewish Museum in New York, an array of caryatid sketches are accompanied by stylized drawings of heads whose facial geometry seems almost obsessively serene, an unobtainable ideal. The curators of both shows insist that they are offering a corrective to the myth of the artist’s life as a wild, reckless, self-destructive ride. But can we separate the two, the life from the myth? If anything, the Tate’s chronological arrangement highlights the biography, and the contrast between the purity of his line and the chaos of his life. This raises the hoary question of whether knowledge of an artist’s flaws somehow devalues the art. In Modigliani’s case, I don’t think this is the case. True, he wilfully, proudly, acted out the Modernist role of suffering artist; he priapically objectified the female body; he embraced the cultural appropriation of “primitive” art without a flicker of unease. His days were drowned in absinthe and hashish—when drunk, he yelled wild bursts of Dante and Villon and Ducasse’s mad, ferocious Chants de Maldoror (a favorite of the Surrealists a decade later). Friends watched him explode with violence or hurl himself against a wall in despair. But oh, how he worked.

Advertisement

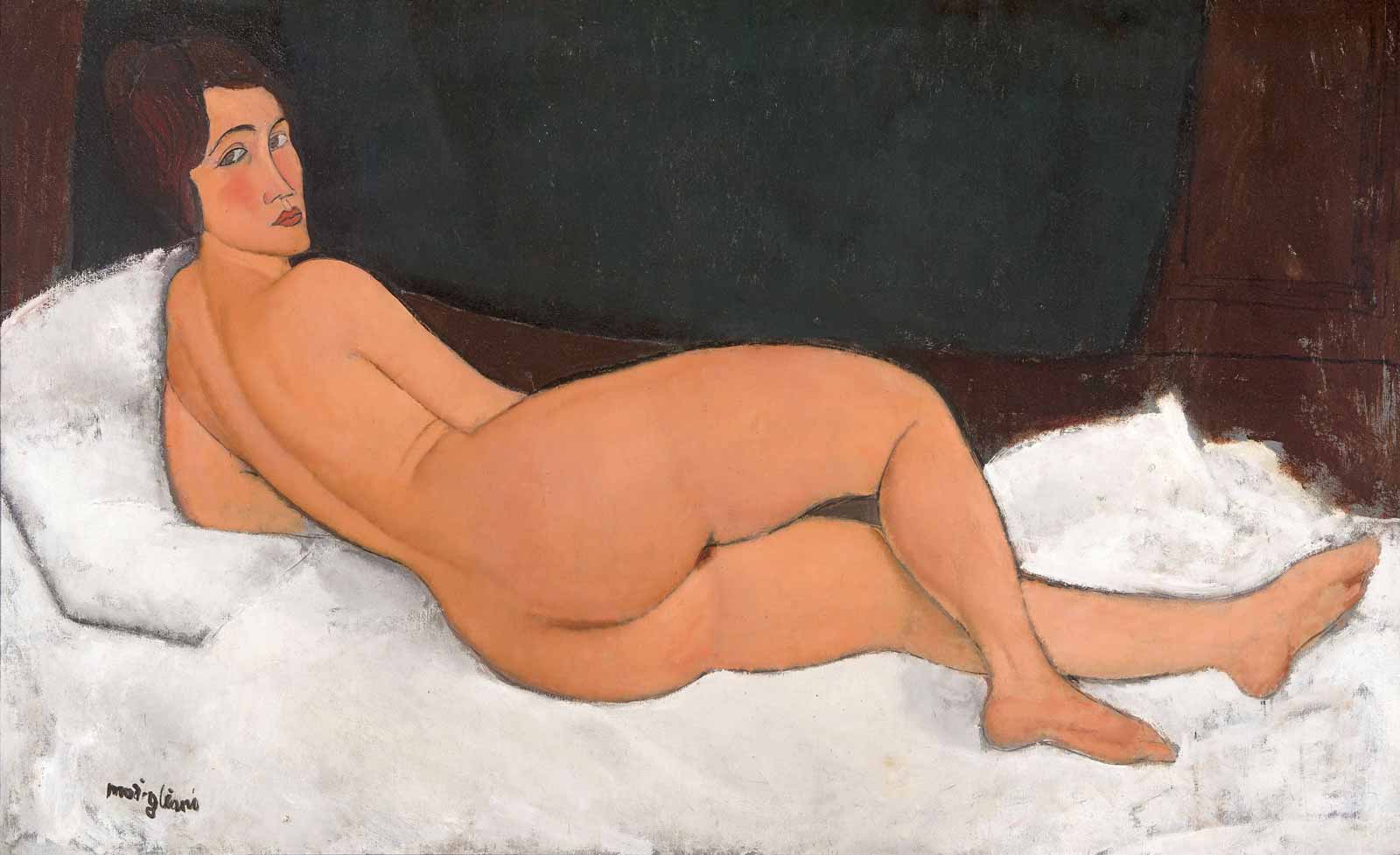

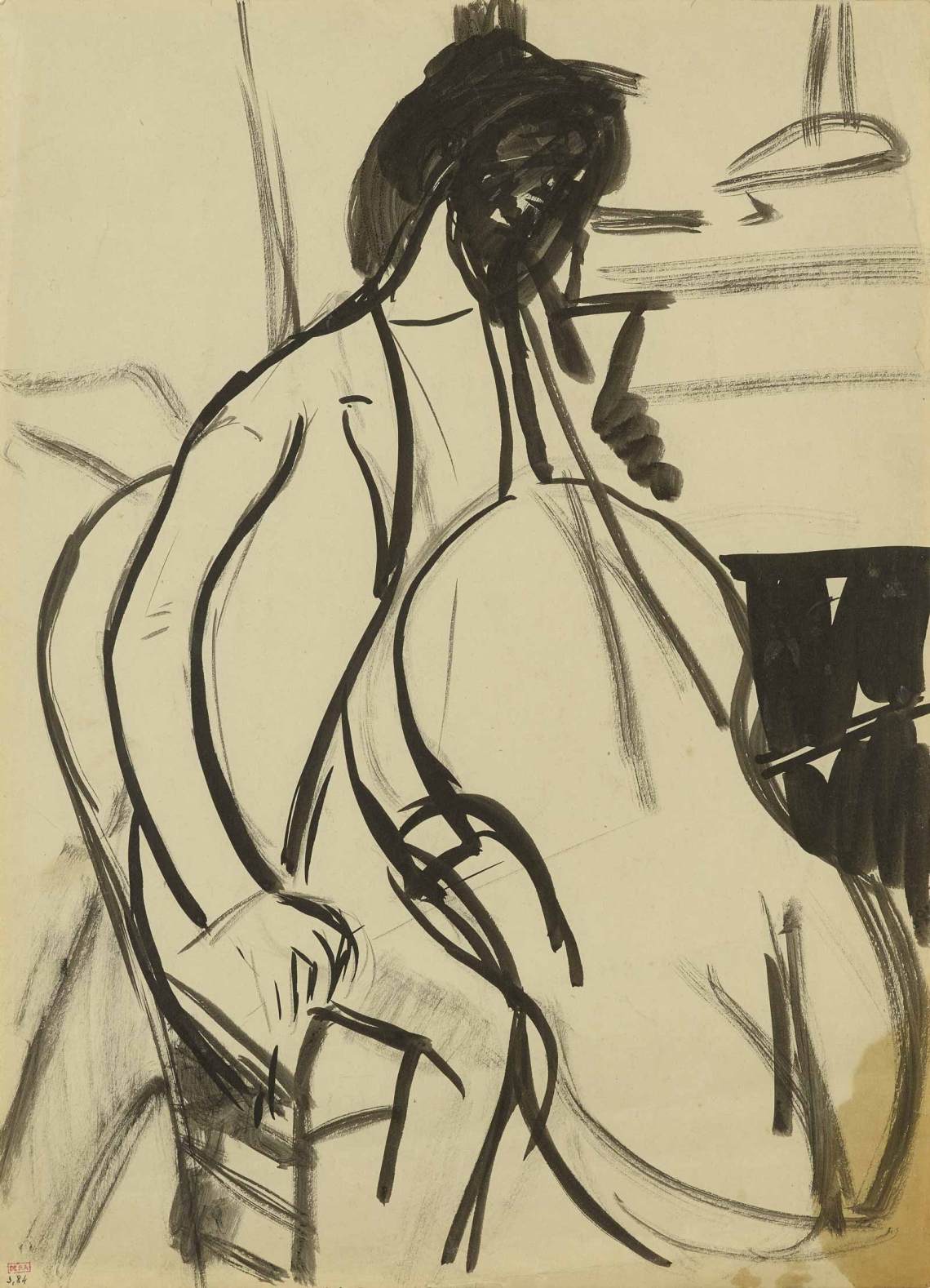

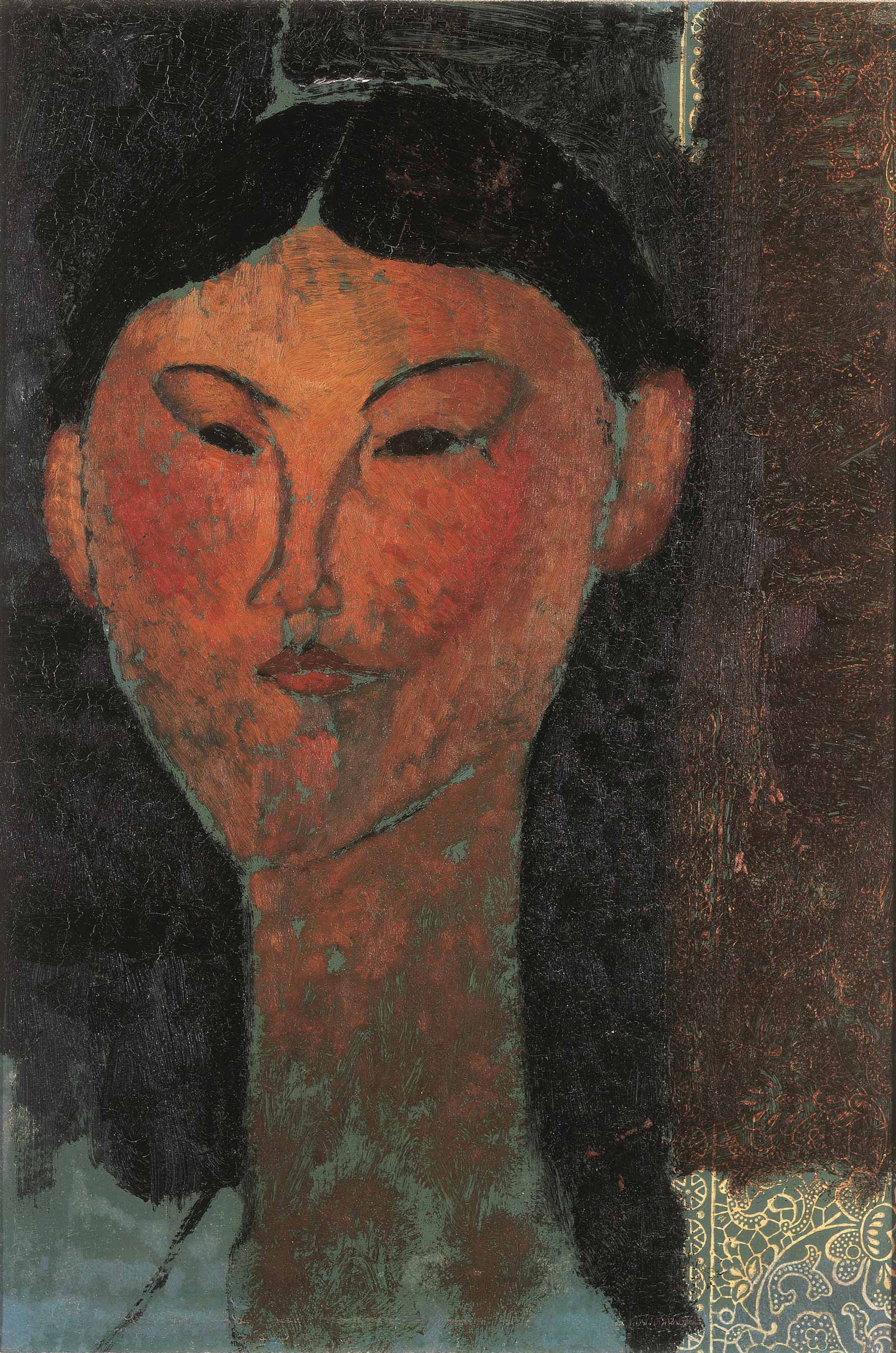

He could paint a portrait in an intense few hours. Several of the drawings on view in New York show his rapid quest to catch a pose—the cellist leaning over his instrument; Paul Alexandre standing stiff against the light in the studio; the tall, beautiful poet Anna Akhmatova, who arrived in Paris in 1910 and became his lover, resting on her couch. Another, more turbulent affair was with the writer Beatrice Hastings, whose portrait stands out at the Tate, with her dark hair, pursed lips and refined, independent stance. But a cooler fascination with the female body shows in the quick, mobile sketches of nudes in the New York show, and in the extraordinary array of nude paintings in London. These sensual images, with curving shoulders, breasts, and thighs outlined in black, with clever references to both old masters and contemporary styles, were a bald commercial venture. The Polish poet Léopold Zborowski, Modigliani’s dealer from 1916, suggested the scheme, provided materials, lent his room as a studio, and kept the finished paintings, paying the artist fifteen francs a day and the models five (a good wage compared to that of a factory girl). But these nudes overcome the cynical appeal to a male gaze. Their bodies are idealized, smooth shapes of sex, but their faces are those of individual women: some gaze out frankly, or peer teasingly, from beneath long lashes; others close their eyes or let their heads loll wearily, as if bored with the whole affair. The smart Algerian model, Almaisa, keeps her necklace; the upright Elvira has a self-contained dignity. It is as though Modigliani himself found peace in their calm stillness, away from his fevered life, away from the mass death and ravages of the war.

In December 1917, a local policeman, shocked by the display of pubic hair, demanded that the nudes in Modigliani’s only solo exhibition in his lifetime be taken down, effectively closing the show. Four months later, he left a Paris battered by artillery fire for the south of France. The friends who went with him included the painter Chaïm Soutine and Modigliani’s young partner, Jeanne Hébuterne. He painted her over and over, with her auburn hair and pale, blank eyes; and after their daughter, also named Jeanne, was born, this seemed, at last, a more settled commitment.

In the Midi sun, Modigliani painted flat, yet expressive portraits of friends, local peasants, and working girls and their children, and, unusually, tried his hand at Cézanne-inspired landscapes. But Paris drew him back. In 1919, he took a studio on the rue de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse: a brilliant virtual-reality installation with headsets at the Tate lets us enter this space, with its bare boards and filtered sunlight, ashtrays and mugs and half-finished canvases. But by now, Modigliani was seriously ill: he died of tubercular meningitis in January 1920, aged thirty-five. Two days later, heavily pregnant with their second child, Hébuterne committed suicide. The deaths enshrined the myth. Yet, above the torment, Modigliani’s paintings soared into the future, sinuous, and full of grace.

“Modigliani” is at the Tate, London, through April 2, 2018. “Modigliani Unmasked” is at The Jewish Museum, New York, through February 4, 2018.